‘Dragon Lady’ by The Geraldine Fibbers

Explosive ’90s banger from mad lyrical genius Carla Bozulich

I feel like I need to learn songwriting again — not literally, but somehow, in my writing. When I was young, I made music. My intellect didn’t hatch until I was seventeen, so before there were books and ideas, I had the guitar. I wrote songs. None that I remember how to play, nor would care to play again — I don’t even remember the weird tunings I came up with in order to find original chords and, well, to compensate for my lack of playing ability; I was for the most part self-taught. But the songwriting was respectable for the alt-rock music that it was. The lyrics weren’t great, my voice wasn’t good, and I couldn’t perform well. But the patterns I found on the fretboard were adventurous and expressive.

That’s what I’m missing now. My intellect gets carried away into such complex, expansive, overwhelming visions. I need to relearn how to be adventurous and expressive in, at tops, five-minute doses. Two- or three-minute ditties would also be acceptable, but I won’t push it. (“If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter,” as said Blaise Pascal, Mark Twain, etc.) In attempt at getting back to that place, I’ll look at a song and think about it. Maybe I’ll do some more of this in the future, but for now I’m starting with “Dragon Lady” by The Geraldine Fibbers.

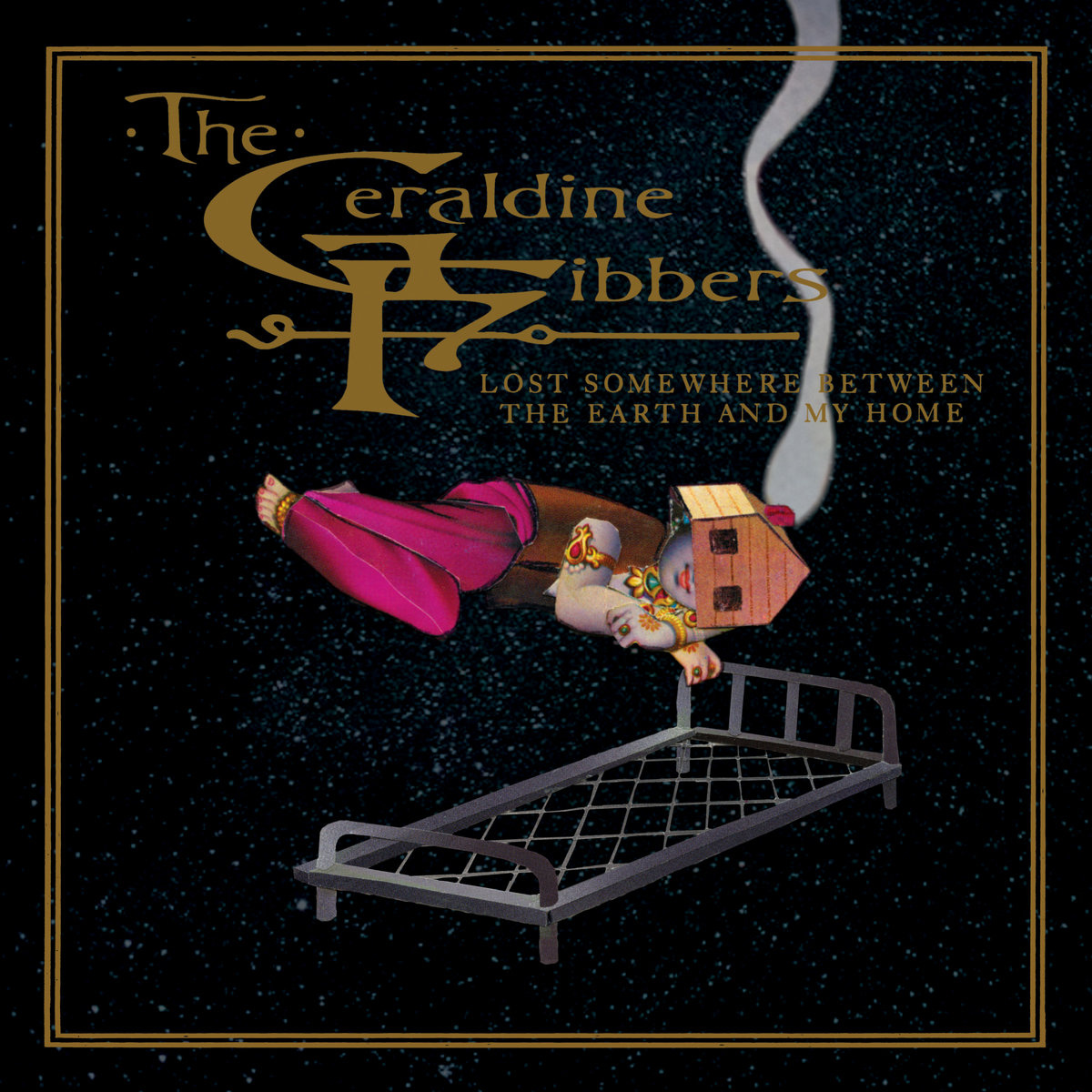

The song comes as advertised, so don’t let this plunge into feminine wickedness scandalize you. But if you don’t mind, say, Nick Cave’s murder ballads all about drug addiction and felonious perdition, by all means proceed. Carla Bozulich deserves the comparison. From beginning to end, you won’t find better lyrics on a ’90s album than on 1995’s Lost Somewhere Between the Earth and My Home, the first of two albums by her Los Angeles–based band The Geraldine Fibbers. This album wasn’t on streaming services for years, and I had shed my old tapes long, long ago. When it finally appeared on Spotify and I revisited it, I was stunned by how amazing forgotten music from the nineties could be. There was such a surfeit of incredible bands, we can’t possibly remember them all — “The underground is overcrowded,” as Archers of Loaf sang, poorly but brilliantly. And in 1995, portals to the underground were still widely accessible in the mainstream, if not for much longer. Lost Somewhere was put out by a major label, Virgin Records, and a music video for “Dragon Lady” appeared on MTV’s alternative late-night programming. In the basement of my family’s suburban house in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at age fifteen, that was my portal.

Here is the playlist on Spotify. The original album ends with track 12, “Get Thee Gone.” If you want a gentle introduction to the Fibbers’ sound, you couldn’t make a better choice than the opening track “Lilybelle”, though make sure you’re buckled in. I had an alarm clock with a tape deck that had the option of playing a tape instead of sounding an alarm, and I remember for a stretch using “Lillybelle” to help wake me up in the morning for school.

And here is the music video for “Dragon Lady”. It is a poor quality rendering of the censored version of the song, which edits out a chunk of four lines between two verses (on account of cussin’). If you just want to hear the full song in good quality, skip to the second embedded video, or resort to Spotify above.

I’ll talk about the lyrics now. They’re not straightforward. “Everything I say is a stupid lie,” the singer claims, untruthfully. Oh, it’s all a lie, but none of it is stupid. Or else all of it is stupid, but none of it is a lie. One or the other, or a mix of the two. This is Dragon Lady speaking, we may presume, though the title doesn’t appear in the lyrics, nor does the singer identify herself.

We know the verse that begins with “Everything I say is a stupid lie” is important because it ends up being the refrain of the song, but that’s not revealed until the end. When we first hear it, we don’t know which of the verses, if any, we will hear again. (Technically there is no chorus here, just three triads of four-line verses, plus one short bridge.) Meanwhile the couple of lines that immediately precede the first “refrain” are so forceful and climactic, it’s shocking to hear them so early in the song.

I got some satisfaction from lifting up your dress

A slap in the face is worth a hundred words

When I open my eyes again I expect that you’ll be gone

But you always do what I expectI’m stopping everything, making fun of myself

Drinking lipstick, tipping bookshelves

Ripping up words that I thought were important

Maybe that’ll blow the window openEverything I say is a stupid lie

I won’t tell the truth even when I die

I’ll rip myself to pieces ’til the end of time

Then I’ll glue ’em back together in a stupid rhyme, yeah yeah-

There’s a story of a girl so sleepy, she could not be aroused

She was kissed by pigs and doctors all over the land

The birds in the trees came down and landed in her hair

They built a nest, and the little birdies hatched it thereTeach me something, rip out my hair!

Send me flying through the air!

Do something, why don’t you fuckin’ do something!

I’m so bored I sleep, yeah yeah!Why don’t you go out and talk some shit!

Stand up, kick ’em all in the family jewels

We’ll watch them as their guts unfold

Then we’ll rob a 7-11 and hit the road, yeah yeah-

I can be quiet or I can be loud

Anything to make my daddy proud-

We’ll take hostages! Make demands!

Set fire to all our best-laid plans!

We’ll assemble volatile explosive devices!

Sell them for exorbitant prices!Purchase an aircraft, learn to fly!

Run out of gas while we’re in the sky!

Automatic pilot and X-Ray Spex!

We were kissing in the cockpit when the airplane wreckedEverything I say is a stupid lie

I won’t tell the truth even when I die

I’ll rip myself to pieces ’til the end of time

Then I’ll glue ’em back together in a stupid rhyme, yeah yeah

“Ripping up words that I thought were important / Maybe that’ll blow the window open” is such a strong, all-encompassing line, with the assonant emphasis on the o’s illustrating perfectly what she’s saying — a lesser songwriter would have saved that for the climax. How do you top it? How do you go beyond it? Beyond it can only be the silence after the song, right? When you put that line so early in the song, either you’re going to have to repeat it, which would cheapen it (what, you didn’t rip those words up?), or somehow you’re going to have to top it, lest the rest of your song suck in comparison. But what happens after Dragon Lady rips up the words she had thought were important is that the window does blow open and she flies through it. Because by the end of the song she’s purchasing an aircraft, learning to fly, running out of gas while she’s in the sky — automatic pilot and X-Ray Spex (presumably the seminal, female-fronted punk band’s Germfree Adolescents is the tape playing on the stereo) — and... switching to a fateful past tense... kissing in the cockpit when the airplane wrecked. Complete rebellion. Utter devastation. But not the end of the song! Dragon Lady dies in the plane wreck, but she lives in death. And she returns without pause to what we now learn is the refrain: “Everything I say is a stupid lie.” She won’t tell the truth even when she dies.

But how does she come to ripping, not just words she had thought were important, but herself, to pieces, ’til the end of time? How does it come to this?

It begins with desire, illicit desire. It always does. She lifts up someone’s dress without consent, a misdemeanor assault. And, ahem, this is nineties alternative music; you can’t assume the person in the dress, or even Dragon Lady herself, is female. In fact Carla Bozulich often writes from a male perspective, and Dragon Lady could indeed be a man in drag. Everything here is queer, but queer at this time is expected to be something that can’t be normalized; it is at base transgressive, a violation, like lifting up nature’s dress without consent. Dragon Lady knows full well she can’t expect anything different from a slap in the face in return, and her desire immediately swings into rage: “drinking lipstick, tipping bookshelves.” Millennials and Zoomers, take note: the unchaste desire you champion is the very source of the violence you decry. The poles of desire and anger are contained within each other. You should not expect anything different. Reality always does what the pessimistic transgressor expects.

Torment follows. But in it, what creativity! What rebellion! The principle and purpose of being human is visible even in corruption and death. Even with demons animating your thoughts. That’s how I think we can fairly understand the conclusion of the quiet verse at the beginning of the second triad, the little birdies landing in her hair, and hatching there an ominous “it”. Sleep, though, is the central image of this middle triad, Dragon Lady’s idea of a sabbath rest. (I’ll spare you the six–seven–eight analysis, but yeah, that’s the fractal structure of the song.) After she initiates the frustrating polarity of desire and anger, Dragon Lady shuts down and sleeps, an image of depression. All the subsequent terrorism, the ominous “it” hatched by the little birdies, we can understand as fantasy, which is not to say it’s not real. Terrorism lives in the mind, so fantasies of it are not without similar effects.

And what is the terrorism rebelling against? Tellingly, it’s the cosmic romance of heaven and earth, soul and body, male and female. This is what offends Dragon Lady the most. She first expresses her rebellion by inhabiting the language of children, telling a perverse fairy tale about a sleepy girl unresponsive to male suitors, “kissed by pigs and doctors.” Doctors would be the ideal mates for women of respectable society, that is, from the perspective of people like parents who have been fruitful and want others to be so also; pigs could mean cops (i.e., authority figures) or any slovenly, repulsive men pejoratively known as pigs. Dragon Lady, preferring her sleep fantasy, rejects the gamut of suitors. She pleads instead to an unnamed other, by proximity associated to the demon birdies alighting in her hair, that it do something to her, anything, even violent ripping, like what she did to her words, as if that was benevolence. The plea “Send me flying through the air,” meanwhile — to be followed up on in the final triad — represents a rejection of the binary of heaven and earth equal to the rejection of the binary of male and female. It will accordingly end in death, the violent ripping apart of soul and body.

But first the plea for self-violence turns into a plea for violence against others. She calls for kicking ’em all in the family jewels, somehow to the point of evisceration, which will be watched voyeuristically. Family jewels of course is a euphemism for genitalia, primarily male genitalia, so an assault on them is a rejection of the fertility of the gender binary, coded as authoritative and valuable. Ironically, this is the point in the song when the first-person plural appears, Dragon Lady becoming wedded to the demonic other, together robbing a convenience store named after its business hours and hitting the road, becoming a destructive force of transience.

Once “they” hit the road, that’s the time in the song for the bridge. It marks the passage from the sabbath rest to the new beginning. Dragon Lady, in a slower, lower-volume, more candid voice, reflects on the song structure employed, commonplace in alternative music since the Pixies, singing, “I can be quiet or I can be loud.” This moment of reflection and candor then gives greater meaning to the follow-up, “Anything to make my daddy proud” — a purposefully ambiguous line sarcastically expressing her angry rebellion against the patriarchy, and sincerely expressing her consequent gleeful subjection to her avian demon teacher. You can’t avoid having a daddy! Dragon Lady’s chosen patriarch then immediately plunges her into destruction. Already the word proud is stepped on by the first verse of the final triad — not quiet like the first verses of the other triads, but loud as hell.

“We’ll TAKE hostaGES!” kicks off such a vicious slew of alliteration, launching from a soft syllable into the rifling of multiple plosives before landing on the affricate “‑GES”. You can just feel the spittle and foam and bile. Given its context of a depressive fantasy, to me it’s an iconic expression of ineffectual, self-destructive wrath. “We’ll assemble volatile explosive devices!” — listen to those stressed long‑i diphthongs on either side of that long‑o explosion in all these Latinate words suggesting the dedication of reason to all this hideous violence; it’s masterful. The shortened meter of “Sell them for exorbitant prices” on the other hand does require the singer to mangle the cadence of “exorbitant” and pause awkwardly before “prices”. Maybe she’s uncomfortable with arms-dealing, but she’s missing some syllables there. If she were from Boston instead of L.A. perhaps she could have said, “Sell them for wicked exorbitant prices.” It’s the most prominent flaw in her wordcraft, but we have to accept the song ain’t about perfection and it’s probably better off for it.

And so, as taught by her chosen daddy, she purchases an aircraft with her ill-gotten gains and makes the departure from earth that she wished for, only when the gas runs out to be pulled by the gravity of reality — which always does what she expects — down into destruction. While it happens, she occupies herself with, well, with exactly the things that have occupied us in the thirty years since the song was written: crucially, reliance on technology (“automatic pilot”), but also pugilistic feminist culture (“X-Ray Spex”), and of course the same transgressive sensual desire which kicked the whole song off (“kissing in the cockpit” — again with the killer consonance!). A slap in the face, worth a hundred words, which indeed is about how long each triad of verses is, by the end of the song has expanded into a fuel-depleted plane crash. And who is the “we” who were kissing? It’s all fantasy. There’s no one there but Dragon Lady and the “it” the little birdies hatched in the sleepy girl’s hair.

What makes the song great, though, is the recognition that the fantasy has limits, that at some point the plane runs out of gas — the admission that “Everything I say is a stupid lie.” At the end of the twentieth century, we were born into this manipulative polarity of desire and anger and all the self-destructive habits and cosmic confusion that ensue from that. We couldn’t help but be in it. That, of course, hasn’t changed, but unlike today, artists back then had a much harder time lying about it, even in cases when they clearly would have preferred to. They couldn’t well pretend we were all going to be okay if we just submitted to technological control and self-affirming therapy. They struggled to look us in the eye and tell us the embrace of transgressive desire was a path to peace and mental health. Many of them may have thought that self-love was the means to utopia, but they did a poor job selling us on the idea!

What they did do was be artists. Especially the independents among them united heaven and earth in the form of meaning and expression, striving to be free from prevailing propaganda. In doing so, they made words and images and music that testified to the nature of creation even when expressing nothing but the patterns of creation’s corruption. They glued their words back together again. That was the solace they could still find in the crater of humanist culture left by twentieth-century abominations. Dragon Lady may be caught in an endless cycle of ripping herself to pieces, along with the words she had thought were important, ’til the end of time — but she still glues ’em back together. A stupid rhyme? A debased form of art? Sure, but the kernel of human reality still exists within it. Our abiding desire for freedom, our beauteous capacity to rebel against evil, they’re still in there sloshing around, yearning for redemption.