Galatians’ shape: Do ye not hear the Torah?

A full-on pentadic fractal, imitating the Books of Moses in an attempt to show the Galatian Christians where they were in the cosmic chiasmus sequence

In preparation for hosting an online Bible study for my parish, I have finally done the deed of uploading the fractal outline of an epistle of St. Paul on my website: Galatians is now live as you read this. Until now I’ve yet to do a Pauline epistle because his writing does not lend itself easily to summarizing and labeling of parts. On my website so far I’ve only uploaded the outlines for larger books because I didn’t want to pad my lists with small works. And regarding Paul, I always figured if I did something like Romans or 1 Corinthians — for which I have full matching outlines — I’d have to include the full text; I couldn’t just do an outline. St. Paul’s arguments really have to be read in detail. You can’t epitomize them except in large, broad chunks that are completely blind to detail. The prospect of doing the full text of a large epistle was always too intimidating to do of my own volition (would they even fit, breadth-wise, on the website?), and no one was asking me for it. Galatians has proven a good compromise. I was able to do the whole thing in just a few days’ work, and now I have confidence and some know-how to do more if called upon.

I’ve also received a tremendous jolt of enthusiasm. Seeing St. Paul’s composition all laid out, such as it is, inspires me endlessly.

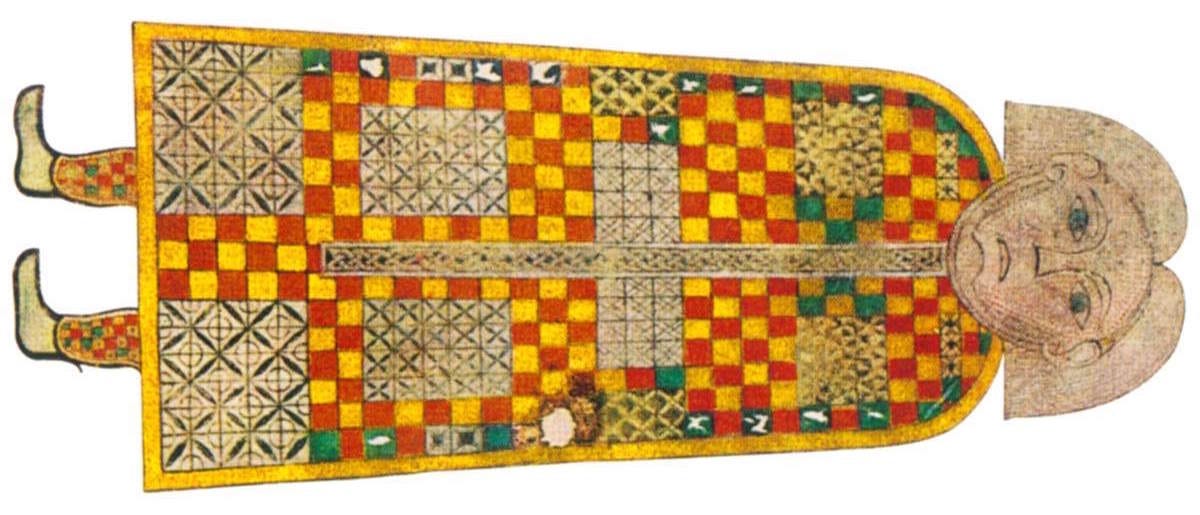

Again, you can see the whole text on my website, but here I’ll do a little introducing. Paul himself does a little introducing, as is his wont, and a little concluding at the end, also per usual. What can be seen as a prologue and an epilogue (Gal. 1:1–5 and 6:11–18) stand apart from the main structure and are called by me the feet and the head due to their shape and the similarity with the Gospel according to St. Matthew. As you can read about on my website, or in a recent Substack article of mine on this Gospel, the artist of the ancient Irish Book of Durrow, who draws an image of the Evangelist Matthew in a shape corresponding with the literary shape of his Gospel, identifies the bifurcated opening section of the Gospel as the Evangelist’s feet and the concluding section as his head.

Well it so happens that Galatians opens with a pair of two neat little fivefold chiasmi that clearly stand apart as a prologue. The reciprocating epilogue at the end is not likewise bifurcated; rather it features a slightly more substantial fivefold chiasmus that summarizes the point of the letter, flanked before and after with its own little feet and head. Why is the opening bifurcated, cloven like a clean animal’s hoof? Why does the conclusion have the same pattern as the epistle in miniature? I don’t know, but feet and head sure seem like useful symbolic images for describing what’s there.

The prologue and epilogue surround the body of the letter, in structure a sturdy, very coherent fivefold pentad of the “Cosmic Chiasmus” variety (yes, I keep that link ever handy). Here’s how it all appears on the website:

Click any of those section headings (on the website, that is, not here!), and the full text of the section unfolds down beneath it. Twirl down all the boxes at once, and you’re scrolling through the full text of the epistle, all parsed and indented spatially so as to reveal the fractal form. Each of the pentadic sections are themselves internally pentadic in their parts — and each of those pentadic parts is also a pentad, except, that is, until the omega-section, where the middle three parts are all internally triadic. It’s interesting how (in chapters 5 and 6, as the conventional numbering system has it) when St. Paul gets to the moral exhortation part of the letter, while still working in an overall pentadic framework, he starts writing on a more cellular level in triads. That makes sense to me because triadic forms are about participation and transformation, whereas pentadic forms are about objectivity and stability of substance, appropriate for use when making solid arguments like Paul’s to the Galatians. Because when Paul is finished, he doesn’t want to hear anything further on the matter.

But let’s discuss briefly how the five main sections conform to the cosmic chiasmus sequence and why this is appropriate to the content.

In the initial section (Α.), Paul establishes his apostolic authority, centering his former persecution of the Church, highlighting the divine source of his revelation, and culminating in how God was glorified in his preaching. His excellence in Judaism and personal calling from God (described with the same language as Jeremiah, referring to God as the one who separated him from the womb) comprise the basis for both his argument and his personal example on display in the rest of the epistle. This is the genesis.

Next (Β.), Paul narrates the conflict that ensued over the question of circumcision once it became established that his mission to the Gentiles was bearing fruits of the Spirit equal to the Judean mission led by the likes of James (the Lord’s brother, not the son of Zebedee who was martyred), Peter, and John. The section centers a confrontation between Paul and Peter that occurred in Antioch in the course of which it is established that by the works of the Torah shall no justification come, but by the faithfulness of Christ, who was crucified and died to achieve what the Torah never could. The focus, appropriate for a beta-section, is on the Torah (from which the covenant of the circumcision comes) and its failure to work justification, as well as the drawing forth of the Church of Christ from any perception otherwise through the dramatic conflict at Antioch — whereby, furthermore, the differentiation is accepted between the evangelic missions to the Judeans and Gentiles within the communion of the faithful, working together like the right and left hands of a single body. But the fullest argument in Paul’s favor lies ahead.

So, in the pivotal chi-section (Χ.), Paul convicts the Galatians as fools for turning away from the Spirit in whom they had made a beginning and worked miracles. The crucifixion of Christ is identified as that which redeems us from the curse depicted in the Torah, Paul using quotations from the Torah to show that this is so. The patriarch Abraham — he to whom the circumcision covenant is initially given — wins the promise of God for his seed not by means of the circumcision, nor by the Torah given four hundred thirty years after, but by his faithfulness. And the seed to whom the promise is given is identified as Christ, the Torah being given on account of transgression in the meantime. Christ redeems us from the curse depicted in the Torah, that is, in the same way that He overcomes death, by undergoing the curse of hanging on a tree. This is the turning point of the epistle because this is the turning point of justification.

And what we have in the next section of the epistle (Ο.) reflects the period of history in which the Apostle Paul and the Galatian faithful find themselves in, the time after Christ’s redemptive work when through Him we have received the adoption of sons and are heirs of the promise of Abraham. Here in history is where theosis is observed happening in the Church, and here in the text is where theosis is observed in Paul’s description of our sonship. No longer a slave as under the Torah, we are now sons and heirs of God through Christ. “And because ye are sons,” the Apostle writes, “God hath sent forth the Spirit of his Son into your hearts, crying, ‘Abba, Father’” (4:6). In the center of this section, Paul describes how he was first received by the Galatians “as an angel of God, as Jesus Christ” Himself (4:14) — this is what Panayiotis Nellas would call “Christification.” Indeed, the faithful such as St. Paul transcend all binary identities and “are all one in Christ Jesus” (3:28). In the Son they are energized by the Spirit and glorify the Father.

As they are living in the omicron-stage of salvation history, and for the Galatians to realize this is the objective of Paul’s letter, the omicron-part of the letter’s omicron-section is something of a fractal sweet spot. This is where I think the most powerful part of the letter is: the “allegory” of Abraham’s two sons Ishmael and Isaac (4:21–5:1). Ishmael was born first, to the bondwoman Hagar and “after the flesh,” that is, by natural means. Isaac is born second, “according to the promise,” that is, miraculously, well beyond barren Sarah’s age of what would have been her fertility. The faithfulness being born from above within Gentiles such as the Galatians is like the miraculous conception within an elderly and infertile womb — whereas the Judeans serving the letter of the Torah even after the salvific death of the Son of God, the promised seed of Abraham, is like the fleshly reproduction by a woman in bondage. These latter sons are to be cast out in favor of the former — according to the Torah itself. In this way, the Torah indicates its own transcendence, and even participates in it by way of its spiritual reading. In the hermeneutics of St. Paul, the Torah itself is redeemed from the curse to which it’s beholden. To this end he uses the cosmic chiasmus sequence after which the Torah is fractally patterned to structure his very argument. The Torah like a tutor is redeemed, its purpose fulfilled, only in its being surpassed.

After all this instruction, justification, and adoption, the time for judgment is due, and the final section (Ω.) addresses this part of the pattern. Those teachers who would have the Galatians enslaved to circumcision shall bear their judgment and should be cut off entirely. Then, that they may avoid such a fate, to the Galatian faithful is delivered moral exhortation, that they walk in the Spirit and not satisfy the desire of the flesh. Just as the fifth Book of Moses, Deuteronomy, lays out the blessings and curses available to Israel, so Paul in the fifth section of his epistle to the Galatians enumerates the works of the flesh in contrast with the fruit of the Spirit. God is not mocked. That which we sow in this life we reap in the harvest. In the light of that harvest, while we have the time, we should not weary in sowing good.

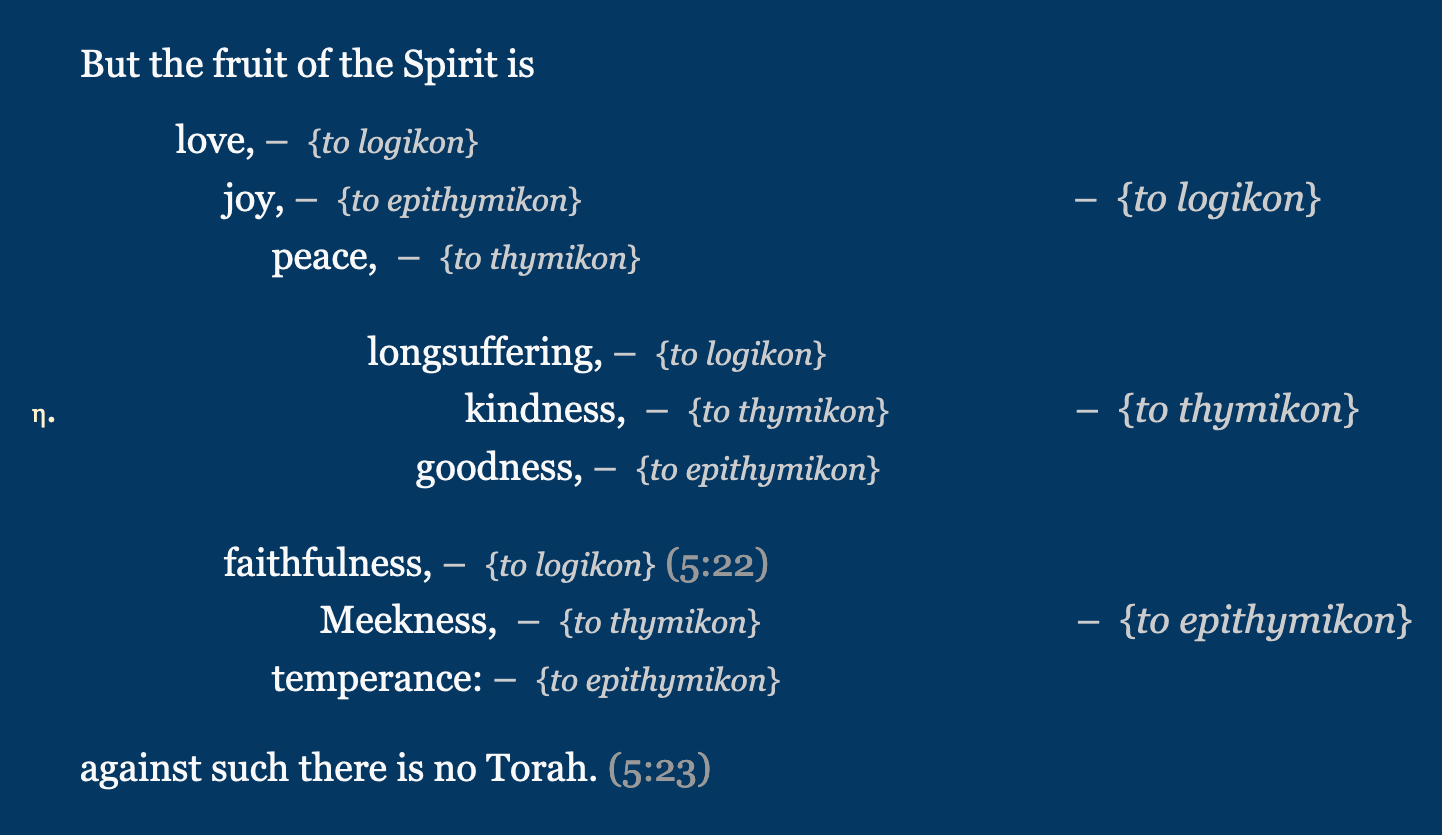

I’ll conclude, then, by sharing the ninefold fruit of the Spirit, which I believe to be a fractal rendition of virtues pertaining to the tripartite soul. This passage is featured in the epistle reading for holy monks and fools-for-Christ’s-sake and is heard frequently in the Orthodox Church. The first triad pertains to the rational aspect of the soul (to logikon), the second to the incensive aspect of the soul (to thymikon), and the third to the appetitive aspect of the soul (to epithymikon). But the pattern operates as a fractal, at least in its virtuous mode. When virtuous, the soul is one and undivided; all its faculties are contained within each other.

One interesting hitch in the pattern here in Galatians is that, whereas the virtue(s) pertaining to the incensive aspect generally precede those pertaining to the appetitive aspect, in one spot it is the reverse: within the first triad, pertaining to the rational aspect, joy precedes peace, which virtues are both very great and all-encompassing, worthy of applying to rationality, but which relative to each other I would associate with the appetitive and incensive aspects, in that order. There’s something chiastic going on between the virtues of the logos and those of the lower passions — almost how the right and left brains operate the chiastically opposing sides of the body. Or maybe it’s the case that within the purely rational soul, the attractive, upward looking, downward pulling force of the appetitive power is free to live adjacent to the rational aspect with no intermediary, as the downward looking, downward repelling force of the incensive power stands guard beneath it. By contrast, within the lower parts of the soul, the striving, martial talents of the incensive aspect are yet required to lead the more vulnerable appetitive aspect safely on its way towards rationality. I think there’s something to this. I think in our current mode of living, spiritual activity initiates with epithymia, but as on the bottom rung. Thymic powers are needed to lead our desire towards logos (and the Logos). But within the hesychastic heart of prayer, they switch places.... I would say it’s rather like a knight delivering his queen to their king after guiding her through a dark and dangerous wood.

I think, moreover, that this setting of the passage, whereby faithfulness is the crown of the queen and love is the crown of the king, sheds light on verse 5:6 — the misinterpretation of which is so central to Protestantism — according to which justification is accomplished in “faithfulness energized by love.” That’s energized, passive voice, not “which worketh”, middle voice, as has been misread by the entire Latin tradition. For that philological insight, see David Bradshaw’s Divine Energies and Divine Action (Iota Publications, 2023), the chapter “The Divine Energies in the New Testament,” previously published in St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 50 (2006).

Glory to God for your work, will this online Bible study you're working on be possible to join if we're from another parish?

Great piece, thanks Cormac for the share! All about 'dem Cosmic Chiasms. Looking forward to those sketches of Romans and Corinthians when you have time to dust those off the shelf. A few thoughts:

- The structure reminds me of the five points in Gary North's thesis too for additional consilience (which is more covenantal in nature) - https://www.garynorth.com/freebooks/docs/pdf/that_you_may_prosper.pdf

- The fractal mapping of the tripartite architecture of the soul (i.e. reason, incensive thymos, appetitive epithymia) to the nine virtues is very fascinating. How do you think about bolstering the case here - for example, why is love-joy-peace more "logos" in nature and longstanding-kindness-goodness "Thymic" etc? And then on the sub-fractal level that one inversion is an interesting nuance but curious how the other virtues relate to each other. Have any Fathers or folks done a more granular mapping here? Seems like an interesting thread to pull on.

- In that line of thinking, would have to go through in more detail but it would be interesting for let's say John of Damascus's work to map scripture to virtue / vices rationale more explicitly. For example the "soul and body having five senses" each potentially corresponding to each of the five points of the pentad fractal structure for NT (Christ) and OT (Adam) respectively [which of course maps to Isaac and Ishmael using your fractal sweet spot]. And then the virtues / vices are potentially the main theses for sub-fractals? But perhaps it's not as rigorous as that

- https://orthodoxchurchfathers.com/fathers/philokalia/john-of-damaskos-on-the-virtues-and-the-vices.html