More on the triadic patterns in the Gospel according to St. Luke

A continuation of thoughts from last month’s post

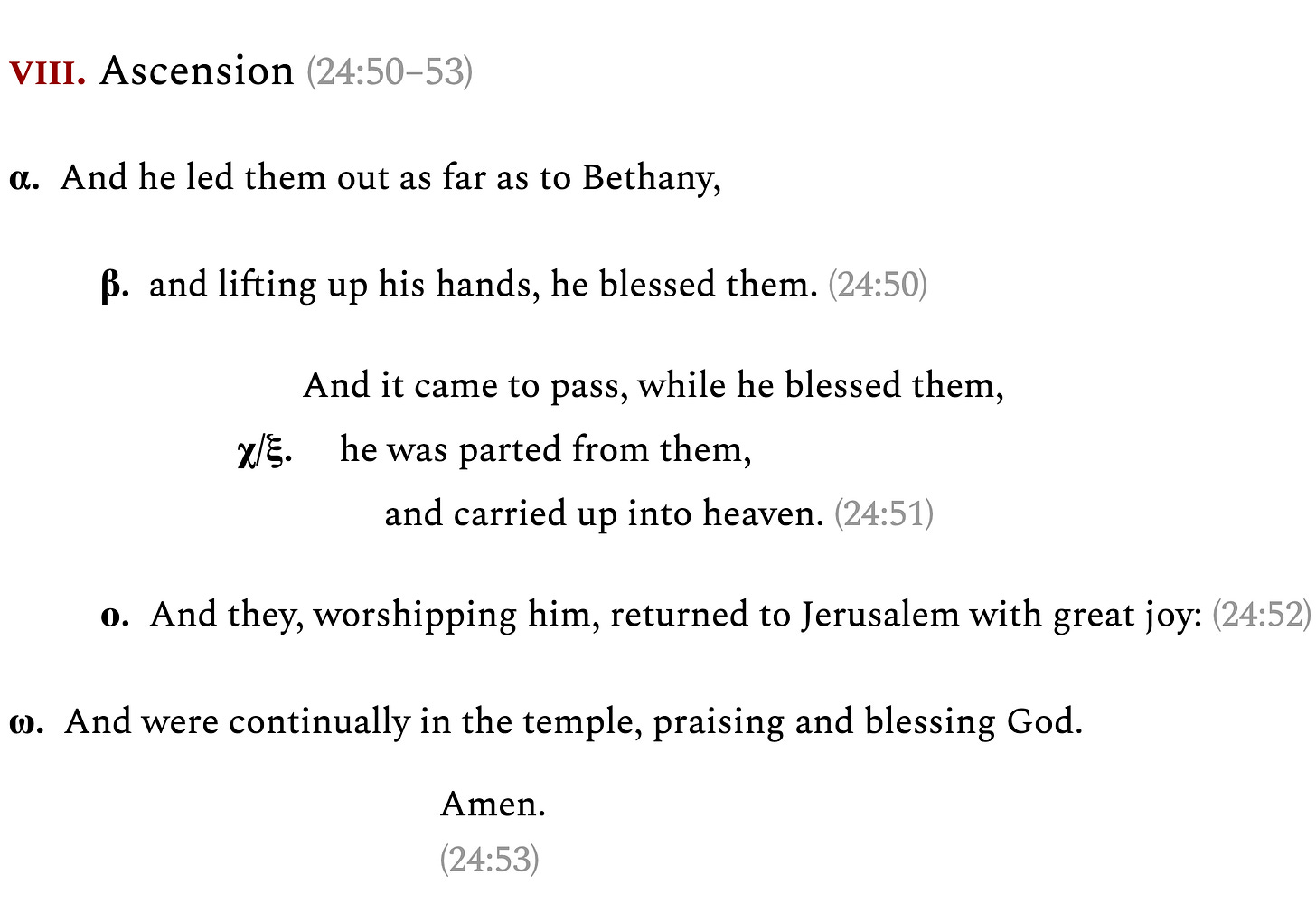

I’ve been working on my octave book, concentrating lately on the Gospel according to St. Luke. What I posted last month, “The triadic fractal at the center of Acts is the same shape as Luke’s Gospel,” was not directly from writings for the book, but was material spun off from those writings. It’s a little disorganized that I did it that way, but I like the article that resulted. I in fact wish the chapter in my book could be more like that article in some ways; I’ve got other fish to fry there, however, like talking about the Enlightenment origins of the triad of transcendentals the True, the Good, and the Beautiful, which Patitsas ingeniously inverts to reflect philokalic spirituality. How many people know that the idea of grouping “Truth, Goodness, and Beauty” comes not from Socrates, Plato, Aristotle or any ancient Greeks, nor from Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus or any of the Scholastics, but from atheist eighteenth-century philosophers like Denis Diderot?

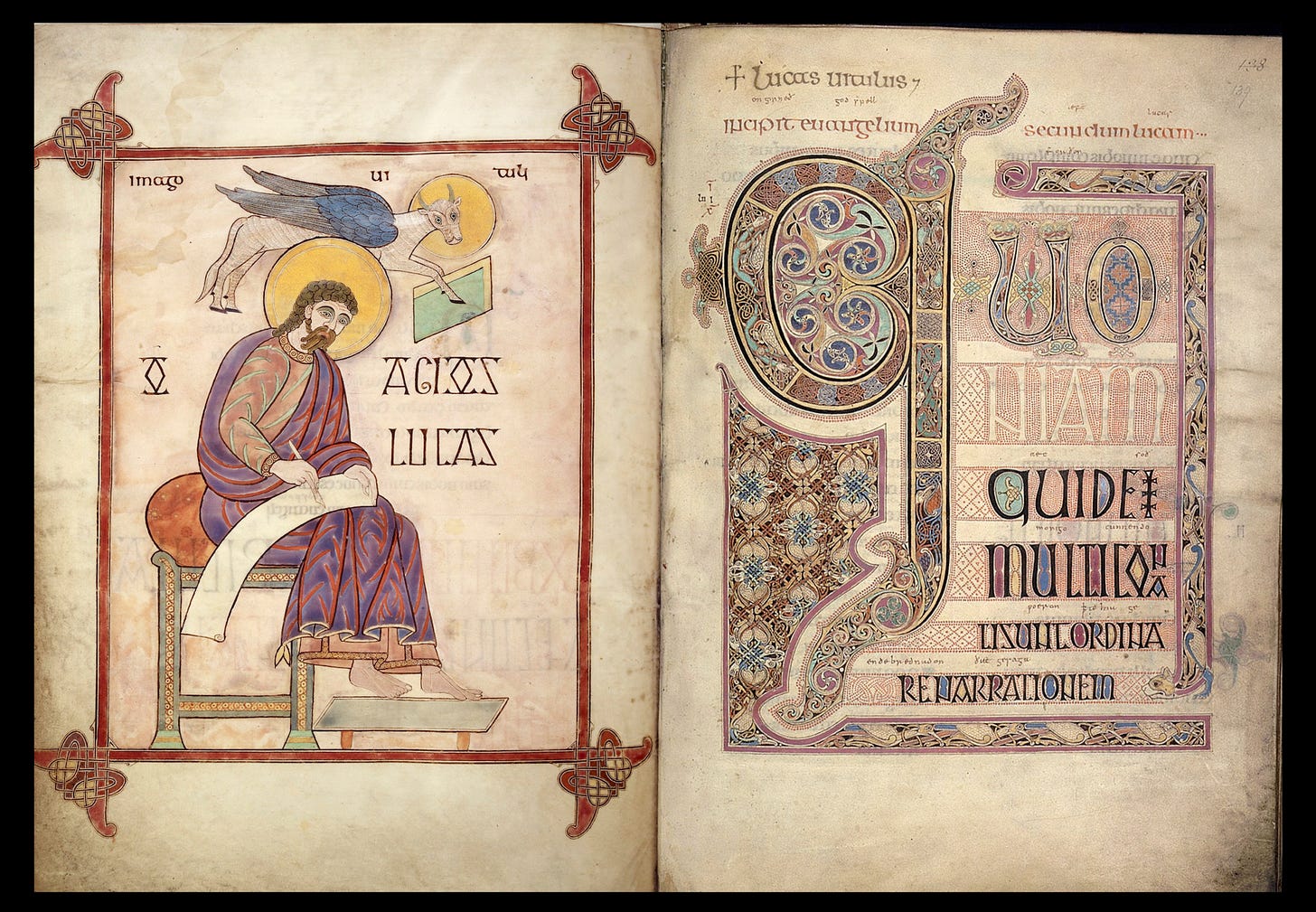

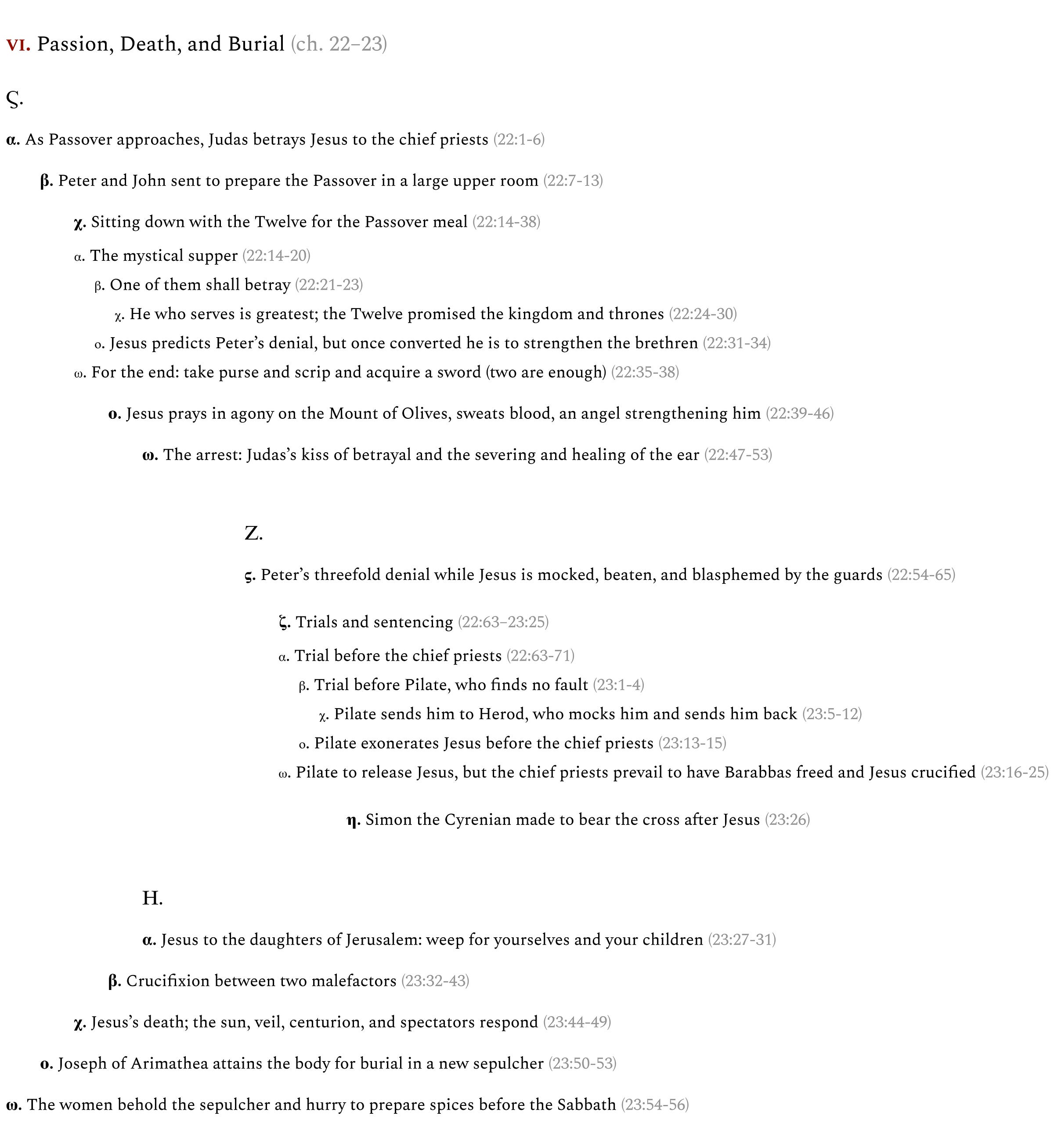

Fortunately I get to that here, as I’ll share some of what I’ve been working on, trying to avoid as much overlap as I can with my previous post. You’ll want at least to review the overall outline of Luke’s Gospel, a triadic fractal (see my website for more detail):

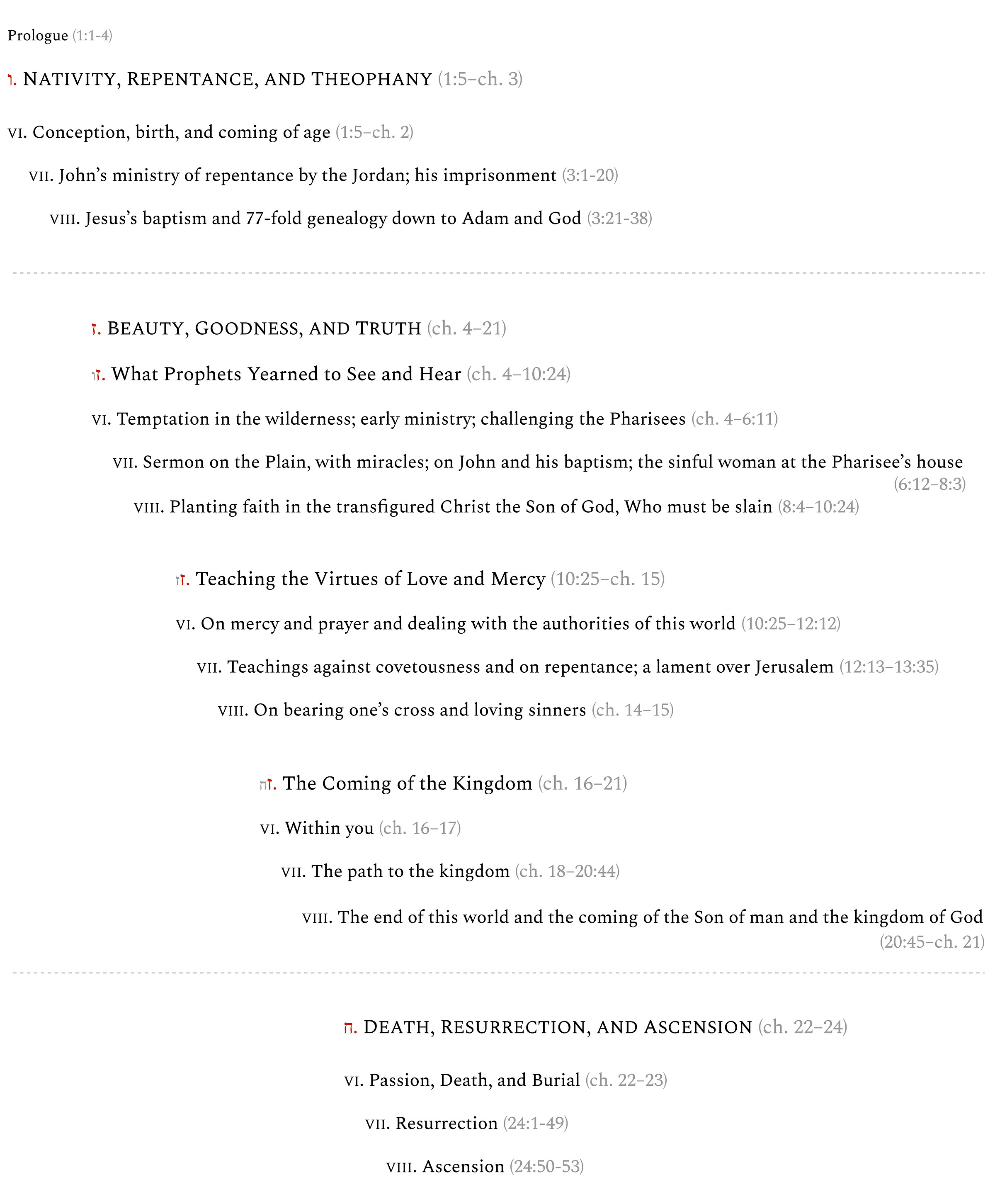

A good text should teach you how to read it, and like Leviticus before it (the chiastic center of the Old Torah), Luke’s Gospel (the ksiastic center of the New Torah) begins with easy-to-follow triadic patterns that induct you into the rhythm of the text. The first chapters tell parallel stories of the miraculous conceptions and births of St. John the Forerunner and Jesus Christ, but these two tracks are repeatedly joined by a third element. After a four-verse prologue, the first two chapters are shaped like this:

It’s a linear triadic shape that is reinforced as a pattern when chapter 3 provides material for parts VII and VIII in describing John the Baptist’s ministry (3:1–20) and then combining Jesus’s Theophany with his genealogy, His divine and human origins (3:21–38). But let’s focus now on the first two chapters which comprise the part VI.

So after the annunciations of St. John and Jesus, there is the meeting of Mary and Elizabeth. In Elizabeth’s miraculous pregnancy, Mary receives the sign confirming her own miraculous pregnancy, and John leaps in his mother’s womb for joy. Filled with the Holy Spirit, Elizabeth hails and blesses the “mother of her lord,” and Mary sings the Magnificat. The nativities occur, again in two adjacent pericopes, and then forty days later the Torah is fulfilled regarding both the purification of Mary and the dedication of her firstborn Son, an event known liturgically as the Meeting of the Lord, whereat St. Symeon the God-receiver calls Jesus “the light of revelation to the Gentiles and the glory of the Lord’s people Israel.” And then, just as each pair of pericopes was followed by a third, so the pair of triads is followed by a third, the scene of Jesus at age twelve, lost to His parents but found teaching in the Temple, “going about His Father’s business.”

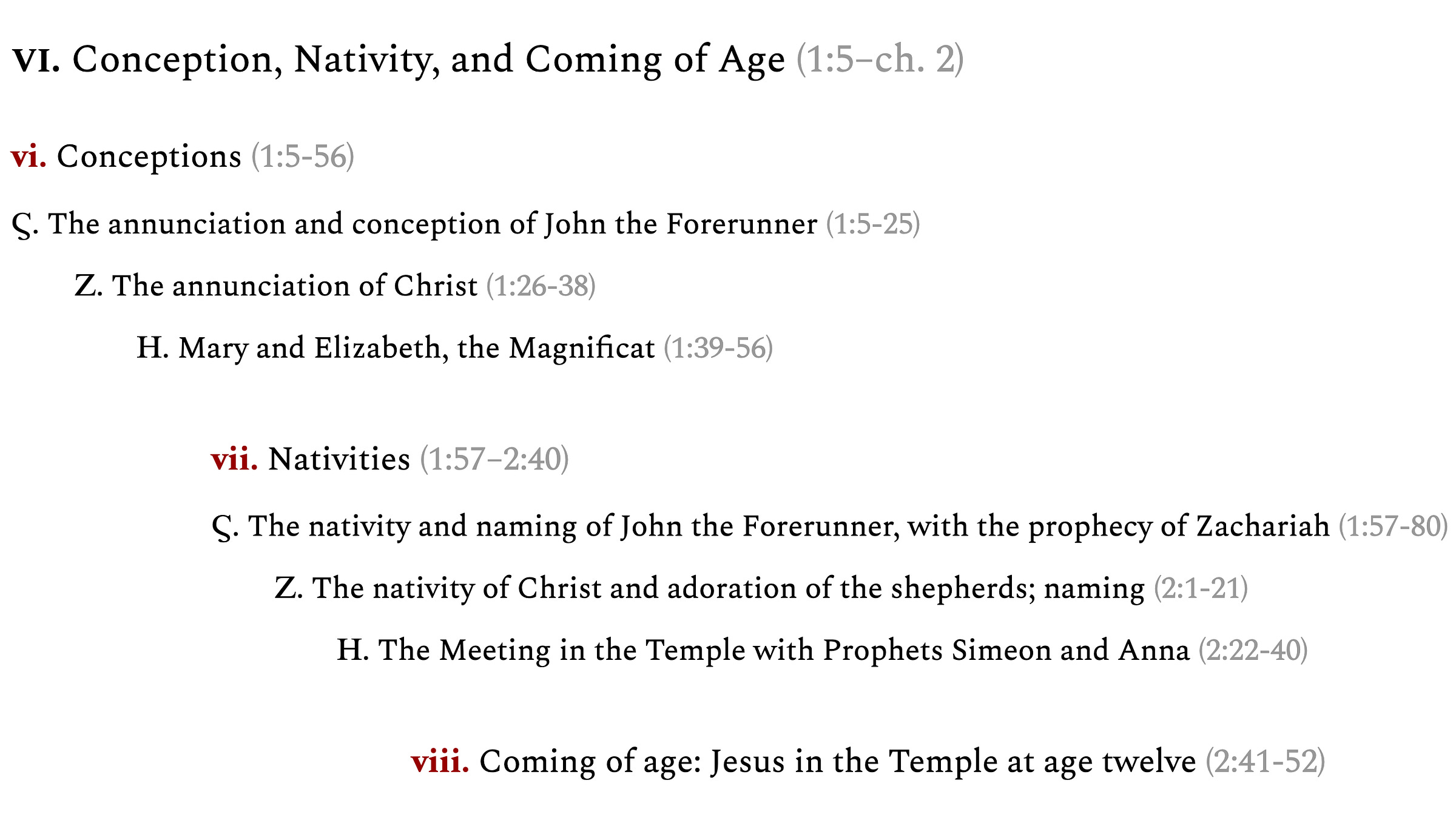

The whole Gospel ends similarly. The risen Jesus ascends from Bethany on the Mount of Olives, completing a textual triad with the Passion and Resurrection chapters. Just as twelve-year-old Jesus was found in the Temple going about His Father’s business, so the disciples, now behaving as Jesus’s Body, return to Jerusalem and are continually in the Temple praising and blessing God.

The pattern of the disciples performing the role of Christ’s Body, and in doing so perfecting a triadic sequence, is reflected also at the center of the Passion narrative.

I had to get creative here with the indentation in order to express an ambiguity of structure. The Passion narratives in all the synoptic Gospels are freestanding chiastic structures, but the Gospel according to St. Luke is also a triadic fractal. There’s a strong sense, given the context, of these chapters proceeding along a Ϛ–Ζ–Η pattern, from supper and arrest, to trials and sentencing, to crucifixion and death. But the first and last sections internally have cosmic chiastic patterns which, besides their internal symmetry, also reflect each other palistrophically. The betrayal of Judas and the chief priests as Passover approaches in the alpha-bit of the stigma-section reflects the faithfulness of the myrrhbearing women as the sabbath approaches in the omega-bit of the eta-section. Peter and John preparing the passover meal in a large upper room in the beta-bit of the stigma-section reflects Joseph of Arimathea attaining Christ’s body for burial in a new sepulcher (a small lower room) in the omicron-bit of the eta-section. The Mystical Supper reflects Christ’s death. The agony in Gethsemane reflects the crucifixion. And for the omega-bit of the stigma-section and the alpha-bit of the eta-section, again the betrayal of Judas and the servants of the high priest is matched with daughters of Jerusalem mourning, Jesus offering to both sets words of rebuke laced with mercy.

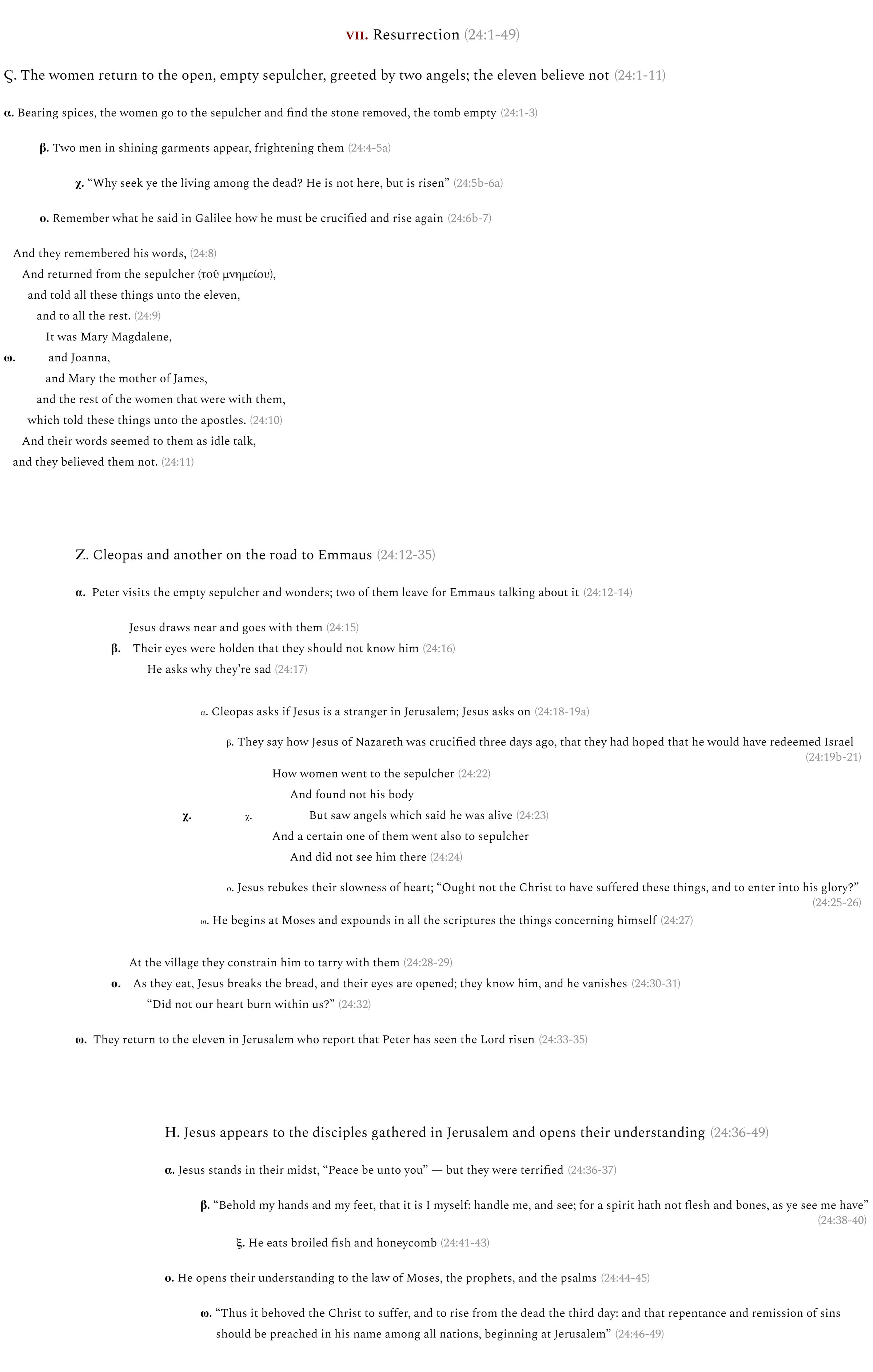

These parallel chiasmi set apart the trials and sentencing of Jesus as a central zeta-section, itself internally flanked by two Simons, one (Peter) denying his rabbi and another (a Cyrenian) compelled to carry Jesus’s cross. Hence with the Cyrenian again a triad is perfected in the third spot with the pattern of someone, typologically a disciple, performing the role of Christ’s Body, as at the Ascension. But between the Passion and the Ascension, of course, as between purification and perfection, stand the luminous Resurrection narratives, clearly a trio of them:

Again the perfection of the Resurrection is that the Christ should have a Body, that He should eat broiled fish and honeycomb — that His disciples, with their minds opened to the words of His revelation, should, like a body with Christ as their head, preach repentance and remission of sins in His name among all nations, beginning at Jerusalem. Thus, if you’re reading the triadic fractal pattern, this is how you understand the Ascension narrative that comes last. The disciples returning to Jerusalem and praising and blessing God in the Temple is the perfecting action of Christ’s Body encompassing all the world, beginning at the nous, embodied in the heart.

And the story of the Christ’s (ח.) Death, Resurrection, and Ascension (ch. 22–24) is itself the perfection of the Gospel that begins with the stories of (ו.) Nativity, Repentance, and Theophany (ch. 1–3). In between lies the zayin-section of the Gospel, all about Christ’s ministry (ch. 4–21). I used not to have a good name for this triply thick section other than “Ministry,” not until I read Timothy G. Patitsas’s The Ethics of Beauty.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Cormac Jones Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.