On a life of Girls Against Boys (the band) (which is all boys)

On the music that stalks me, the rhythms that live in my marrow, and the crashes I’ve narrowly survived

Embedded above is the 1995 music video directed by Kevin Kerslake for Girls Against Boys’s cover of Joy Division’s “She’s Lost Control.” It is what I have long pointed to as my favorite music video, or at least the one I am most impressed by artistically. It only played on MTV once. I can say that with confidence because back in the day when it came out, I was watching 120 Minutes Sunday nights from midnight to 2 am every week and had been for a couple years. 120 Minutes only played this video once, and that’s the only place on MTV you would’ve seen it. It’s strange that they only played it once, because Girls Against Boys normally got more airplay than that (if barely). But this song wasn’t from any of their albums; it comprised their contribution to A Means to an End: The Music of Joy Division, a tribute album of Joy Division covers, and a stupendous one at that. Revisiting it now, I think about the role the band played in my life, the direction of this particular video, and the nature of the music.

Regular readers of mine know (for example, from this post) that Low has been my favorite band since about when The Curtain Hits the Cast came out, in 1996. I knew and loved them before, but that is when they ascended to first chair in my mental rock orchestra. The band they displaced was Girls Against Boys.... Now, that’s a strange combination, but as a teenager I was versatile — I did manic and depressive. While Low plumbed the depths of despair with drawn out, time-expanding vocal harmonies set to minimalist songwriting measured with but a snare drum, floor tom, and ride cymbal, played sparsely with fan brushes, Girls Against Boys maniacally blasted heavy, cruising rhythms, driven by not only a full drum kit, but two bass guitars. The unfortunate labels slapped on these two bands’ unique sounds were “slowcore” for Low and, for Girls Against Boys, “velvet metal.” Their sound was as jagged as metal, I suppose, but the way they shaped the texture of time with rhythm was as densely pleasurable as velvet. The uncanny combination was ripe for an anxiety that was pure:

That’s “Bullet Proof Cupid,” one of their better-known songs. There’s actually only one bass guitar on the track, as this is one of the times Eli Janney switches to keyboard — the left side of the keyboard mostly, so it fits with the rest of their sound. But notice how I sold them to you on their rhythm, and here, instrumentally, it’s mostly straight eighth notes in common time. The discordant, driving melody, however, brims with a rhythm that defies the beat, creating this inexorable tension that suggests some strong desire for syncopation, relieved somewhat in the vocals, but never really satisfied. When the song explodes, while retaining this tension, it feels apocalyptic.

That sense comes across in their other songs with more varied, if always repetitive, rhythms. Behold in “Psychic Know-How” how the looped notes in three-four ever cycling downward are overlaid with a riff jumping back and forth on a four-four beat. And then comes the howl:

That’s the mania I’m talking about. This thymic striving for control amid rigid, repetitive structures while never attaining it, being constantly overwhelmed by an unleashed chaotic energy — that’s the spirit of rock ’n’ roll. Our souls are spun out of control while at the same time locked in a cycle of verse-chorus-verse-chorus. If ever one tries to escape the pattern via a bridge, it leads right back into the same cycle of verse-chorus. It’s simultaneously centrifugal and centripetal. It’s the pattern of the passions, of course.

But this brings me back to “She’s Lost Control” and the music video I posted at top. Girls Against Boys and Low may be polar opposites, but the Joy Division tribute album is the one place where their careers overlap, revealing their positions on a singular axis — the two best songs on A Means to an End are by Low and Girls Against Boys. If you saw my post sharing a chiastic playlist inspired by the solar eclipse, then you’ve already encountered, at the playlist’s center, Low’s cover of Joy Division’s “Transmission”: “Waiting for a siiign... Waiting for a siii-iiign....” The rendition highlights that band’s usual yearning for spiritual fulfillment, made to be satisfied merely in itself. “She’s Lost Control,” meanwhile, has got all the anxiety suggested in the title, though the presence of a female subject brings an epithymetic angle to the mania. Implicitly this “she” lives in a man’s world (Joy Division is a quartet of men, just like Girls Against Boys), and if she has lost control, that means something else has it over her. The video, directed by Kevin Kerslake, visually captures this tension perfectly.

Kerslake, back in the day, was a big name in music videos for alternative music, establishing his cred in the scene immediately with his first effort, for Sonic Youth’s 1986 song “Shadow of a Doubt” (see video embedded above). Indeed, it’s probably the best music video of the ’80s, Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” notwithstanding. Featuring Kim Gordon sitting on top of a train projected behind her using the magic of low-grade video technology, the spot was instantly legendary for capturing the oneiric quality of the music. And already here Kerslake was using long, slow-moving takes of sustained attention to seize the viewer’s mind. But that music’s on the Low side of things. Mostly for his music videos in the early ’90s, he was illustrating fast, jangly rock music, for which he adopted the quick-editing style so common on MTV. “Cherub Rock” by Smashing Pumpkins would be a prime example. Oh, and he also did every Nirvana video off Nevermind except “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” winning an MTV Video Award for “In Bloom.” His video for Mazzy Star’s “Fade Into You” took a slow, acoustic ballad with dreamlike slide guitar and gave it not the long sustained takes you might expect, but quick overlapping edits of slow-motion, 8-mm photochemical mementos, drawing heavily from the fragmented home-movie style pioneered by experimental filmmaking legend Stan Brakhage.

Kerslake was no doubt very film literate, and his 1995 video for “She’s Lost Control” smacks every bit of an artist who had just seen Hungarian virtuoso Béla Tarr’s 1994 seven-hour-long masterpiece Sátántangó and said, “That.... I need to do that now.” The hallmarks of Tarr’s mature style are plainly evident: rich, especially grainy black-and-gray film (with no true whites), a moving camera ever-conscious of off-screen space, as from the perspective of a phantom, and minimal, very deliberate cuts. The three-and-a-half-minute music video has just two cuts joining three sustained takes. The sustained attention functions as a bid for control, an attempt to possess the objects of one’s gaze. The members of the band have a hard time cooperating. Drummer Alexis Fleisig, for one, sits in the back rooted in place, visually and musically, providing a beat that holds everything down. Guitarist/frontman Scott McCloud can be counted on to stand in the middle by the mic ... but only for so long until he can’t stand to anymore. The duo of bassists driving the song on the left and right poles of the stage, moreover — Johnny Temple at right and the über-hyper Eli Janney at left — will slip out of any composed shot they’re placed in.

Here the feminine camera feels a composition is in her grasp:

Here, the bassists de-center the image; Johnny rocks out of position too far into the center, and Eli pops out of the camera’s orbit entirely:

Finally Scott — like a man’s reason when pushed and pulled by desire and anger — cracks from the pressure of confinement, knocks over the microphone holding him in place and exits stage left:

Typical, unfaithful men. They always leave.

So much for the first shot — the camera has lost control, and the lower passions in the form of the two bassists dance over the absence of fallen reason. This is “boys against girl,” no? The girl being the camera? Yes, but it’s also the incontinent desires of the men — the “Girls” — against all the woman’s attempts to control: the “Boys.” It’s epithymia versus thymos. All men in alternative music in the mid-’90s (the Clinton era, not insignificantly) were defined by their incontinent desires; see Greg Dulli, Lou Barlow, Thurston Moore, etc.

But let’s return to the video and see how the camera does once the editor gives her another shot:

Okay, cut to Alexis in his Carnegie Mellon University tee — a handsome guy (they’re all handsome) and a reasonable move. He’s reliable. Can we center him in frame? No? It feels like an attempt was made, but this was the best the camera could manage to see through his buddies to the back of the stage. The legacy of Edgar Degas is strong here. He was the artist a hundred fifty years ago who, inspired by photography, taught us to see the beauty of the world not in symbolic compositions lending spiritual order to reality, but in disconnected fragments dominated by empty spaces — materialistic snapshots, like this:

Attempting to ground her control in the drummer, then — albeit from a materialistic perspective that hosts no spiritual principle other than emptiness to hold things together — the camera next tracks backwards, past the horizontal neck of Johnny’s bass, to find a horizontal Scott, face, hands and knees on the floor, needing to lip sync but not willing to stand in the center or even pick up the microphone.

Eventually Scott will drag himself and the microphone up from off the ground, but the camera has lost her grip and needs a new beginning. A second cut is made, and the third and final shot is initiated. It didn’t work to ground the camera’s gaze in the drummer Alexis at the back of the stage; the frontman Scott has proven wholly untrustworthy; left-bassist Eli is a hyperactive lunatic... which leaves us with right-bassist Johnny.

Holding the underlit Johnny in frame is unsuccessful from the start, and already the shadows of his bandmates dancing around him tell us there is no hope of expanding any control to the rest of the band.

The camera comes unhinged, losing contact with the ground itself and floating amidst the pipes overhead. Spinning slowly out of control is all it has ever been able to accomplish in its concentrated effort not to spin wildly out of control. Yet it remains tethered to the objects of its desire, which it will never hold in its power. The whole video holds together in a constant flow, a little symphony of chaos. Centrifugal, and centripetal. A slow, dissipated, anxiety-inducing chaos of motion — not outside the grace of providence — swirls amidst the black-and-gray grains with no true whites.

I drank in this music, and these images, as a kid, because I related to them so closely. They faithfully expressed the fallen world in which I was granted consciousness. Plus, their incontinent desires matched my own and encouraged their thriving. It felt like living at the time. Something was animating me; we all naturally crave to be animated by something. Well, through the mystery of perception, I became united with this band’s music as a matter of identity. The rhythms of their songs became encoded in my muscles, my bones, my marrow. To this day, if you put me in an auditorium to clap applause with a large group of people? I will start clapping out the syncopated rhythm of “Vera Cruz.” It gets lost in the din as everyone else in the place claps to regular beats like normal people, but that is what will happen. It’s not that I listen regularly to this band still. I do not. I don’t have to. The dye was cast before I knew left from right. I was born into a chaotic maelstrom of passion confined by the polarity of pleasure and pain. The art I immersed myself in at least had the virtue of laying bare the situation.

But my life was at risk.

In 1997, when I was seventeen, within the span of four months, I twice totaled a vehicle at high speeds while making a long-distance drive on a highway. The first time was in broad daylight on a right-as-rain road drawn on the map with a ruler. What happened was, I got mildly distracted while making the day-long trip from Cornerstone Music Festival in Bushnell, Illinois back home to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I was alone in the car, my family’s old station wagon (both of these instances were single-car accidents while driving alone) and didn’t have time to waste. So I resolved to eat while driving.

It was yet the morning hours, I had made it into Indiana, and I wanted to eat some apple sauce. I had a jar of apple sauce in the cooler behind the passenger seat. So, with Girls Against Boys blaring on the stereo, and with one hand on the wheel and my eyes locked on the road, I reached back, opened the cooler, and felt through it until I found the jar of apple sauce. I got the apple sauce and closed the cooler. The problem was I needed a way to eat it. I had paper bowls and some silverware in the back seat. All I had to do was — one hand on the wheel and eyes still on the road — reach back, lurching with my whole body, and root through some things to acquire a bowl and a spoon. Then, my body now rested back in the driver’s seat, I had to open the jar and pour the apple sauce into the bowl resting in my lap, while keeping my eyes only periodically on the road, lest I spill the apple sauce. I poured the apple sauce without spilling it. So far, so good. Why wouldn’t it be? Then, I didn’t want the rest of the apple sauce to go bad in the hot car (it was a bright, sunny day), so, balancing the bowl of apple sauce in my lap, I had to reach back behind the passenger seat — with eyes on the road — open the cooler, and put the apple sauce jar back in its place. Done. I had my apple sauce, and I was driving.

I ate the apple sauce. I finished the bowl as much as I could, but there was a sticky residue left in it. I placed the bowl and spoon on the passenger seat for potential reuse (there was a long day yet ahead of me), but the weight of the spoon was tipping the paper bowl over. I didn’t want to get anything sticky on the seat, and I really didn’t want the reusable spoon to get dirty by rubbing up against the fuzzy upholstery. So I was trying to balance the spoon in the bowl against the back of the seat, so that it wouldn’t tip over. This was doable. As I did it, though, I was distracted just long enough that I drifted off the road just a little bit, not a dangerous amount. However... when I heard the gravel underneath the right-side tires, I startled myself and overcorrected when swerving back onto the road. At sixty miles per hour, stereo still blaring, I lost control of the vehicle and began fishtailing. The back of the car could not be kept in back of the car. After much swerving I turned perpendicular to the road and went nose-first in the ditch to the right, just ten feet past a large tree. My car, still full of velocity, sprung up and did two full sideward rolls in the air before landing upright just twelve feet shy of a telephone pole.

The car was utterly destroyed, but absurdly, the stereo’s blaring persisted without interruption. I had been listening to Girls Against Boys’s album Cruise Yourself, naturally. Safely buckled in, I had cuts all over my knuckles from the shattered windshield and a gash above my eye where my glasses hit the steering wheel (this car was older than airbags). But the first thing I did when the rolling was over and the violence stopped was turn off that blasted music. The still functioning stereo, drumming on as if it wasn’t the first thing that should have crapped out, was pure mockery to my soul. I hit the power button on the stereo, unbuckled my seat belt, pushed the car door open, ran out onto the highway with no one else around and — greatly to my shame — cursed God to the heavens. Yeah... as if it was His fault. As if He wasn’t just responsible for saving my life! It was completely irrational. I thought I was Christian at the time; I had no idea there was such incredible blasphemy inside of me. But cursing is like spiritual flatulence. Something painful disturbs you, and suddenly all this malodorous evil you’ve been mindlessly consuming bursts out into the air around you.

So much about that first car accident was comedic, I mean, just ridiculous. Driving down a perfectly straight road on a perfectly clear day, I just blew up my car all by myself, apropos of nothing, and walked away without any major injury. The contents of the ice cooler were everywhere. All my gear from a week of camping out at the festival, enough to fill up the station wagon — was bent and spilling here and there. I had one of these tape cassette containers for my music, plastic holders kept together by zippered cloth. It held, like, one-hundred twenty cassette tapes, and of course I kept it open and within reach so I could pick out my music. The tapes were everywhere, the cases in pieces, all over the car. I couldn’t even find the spoon I was trying to balance....

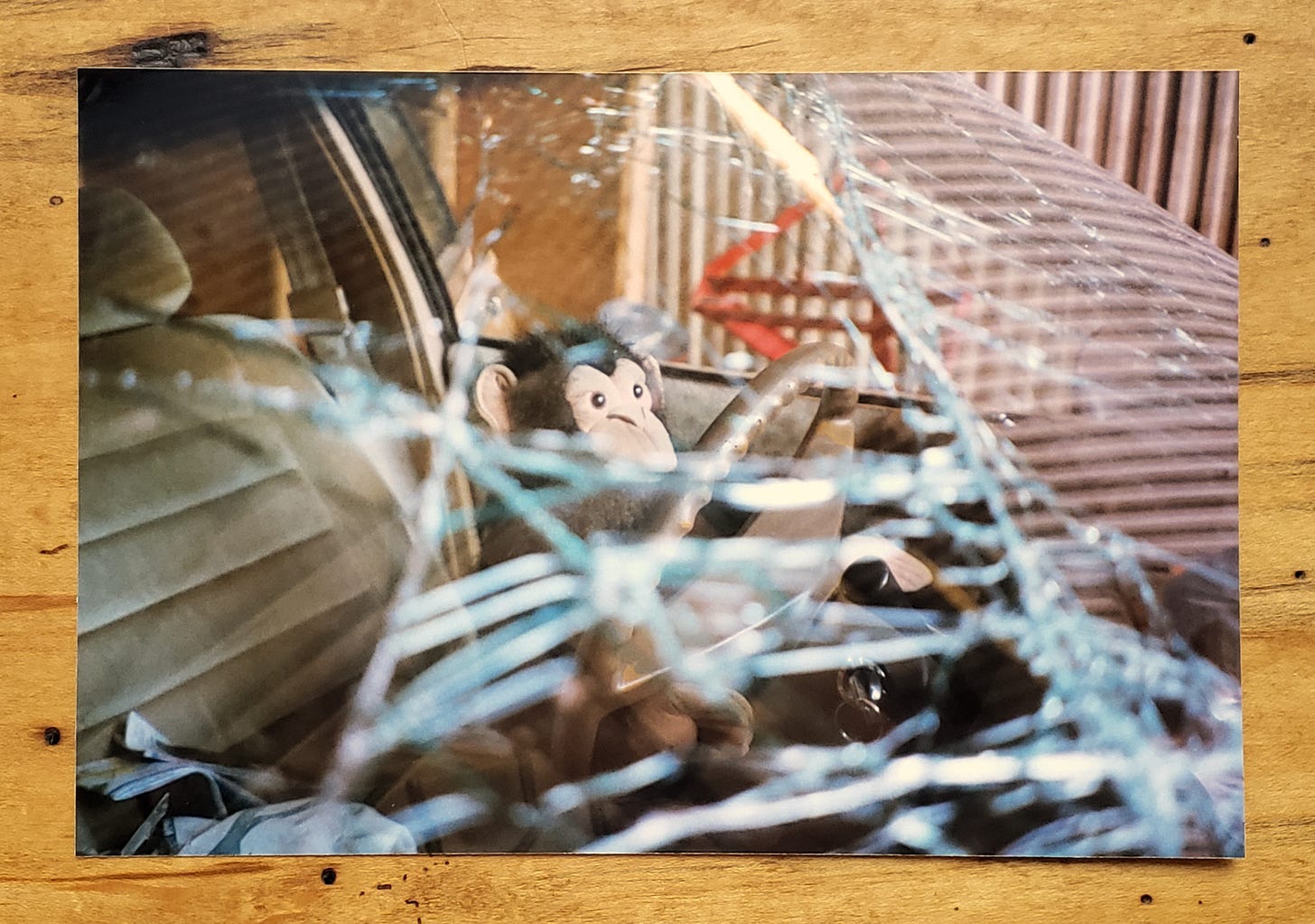

A truck drove by and stopped; emergency services were called in. I was required to take an ambulance ride to a hospital though there didn’t seem anything major wrong with me. As it happened, the paramedic sitting in the back of the ambulance with me looked exactly like Dana Carvey. The spitting image. I mean, as far as I knew, this was Dana Carvey; I was riding in the back of an ambulance with Dana Carvey. And as I was, I realized something else. I had handed over my wallet to a policeman so he could have my license. But I had done something to the license that I had forgotten to undo. As a joke, I had taken a head shot photograph of my stuffed chimpanzee, which came from a contact sheet I had made in photography class, and taped it over my picture on my driver’s license. That stuffed chimpanzee (Monkey was his name) was in the car amidst all the rubble, alongside his friend, a stuffed orangutan. So I imagined this unsuspecting cop opening my wallet after I’m gone, pulling out my license — seeing the image of Monkey where a human should be — looking up and seeing Monkey laid out in the vehicle, and saying... “Wait a minute...!” And I’m sitting in the back of that ambulance with Dana Carvey, laughing hysterically, completely unable to describe what was so funny.

Either accident easily could have been fatal, but both times I walked away. The first time, it was ridiculous comedy, but the second time it was sad tragedy. In the four months since my last accident, my mother and I had moved out of my childhood home and to another state. I had lived in that house since I was six months old. Its rooms and stories were the shape of my soul. Now, I was to be exiled. It was my final year of high school, but my mother had to get a teaching job since my dad had left. We moved from the bustling suburbs of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to the rural countryside of central Virginia, where we knew no one — where it was just me and my mom surrounded by our neighbor’s cattle. As a consolation prize for her abandonment, my mother had received a big new car, a Ford Explorer SUV, which she loved. One weekend in late October ’97, I was allowed to borrow it to drive over the mountains back to Pittsburgh. Low was performing over a toy store on the Southside. I got to visit with my friends, see the best Low concert I’ve been to in my life (of many), and stay in our emptied-out old house which hadn’t been sold yet. These are very plaintive memories. The first time you return to a home you’ve moved away from is always the most emotional.

On the way back to my mother in Virginia, that Sunday night, it was dark and stormy, but I was driving at full speed, eager to complete the four-hour journey. On Interstate-70, still in Pennsylvania, on an Appalachian mountaintop nearing the Piedmont below, I went into a curve paying full attention. But before I knew what happened, the whole car was sitting sideways on the side of the road and there was an airbag in my face.

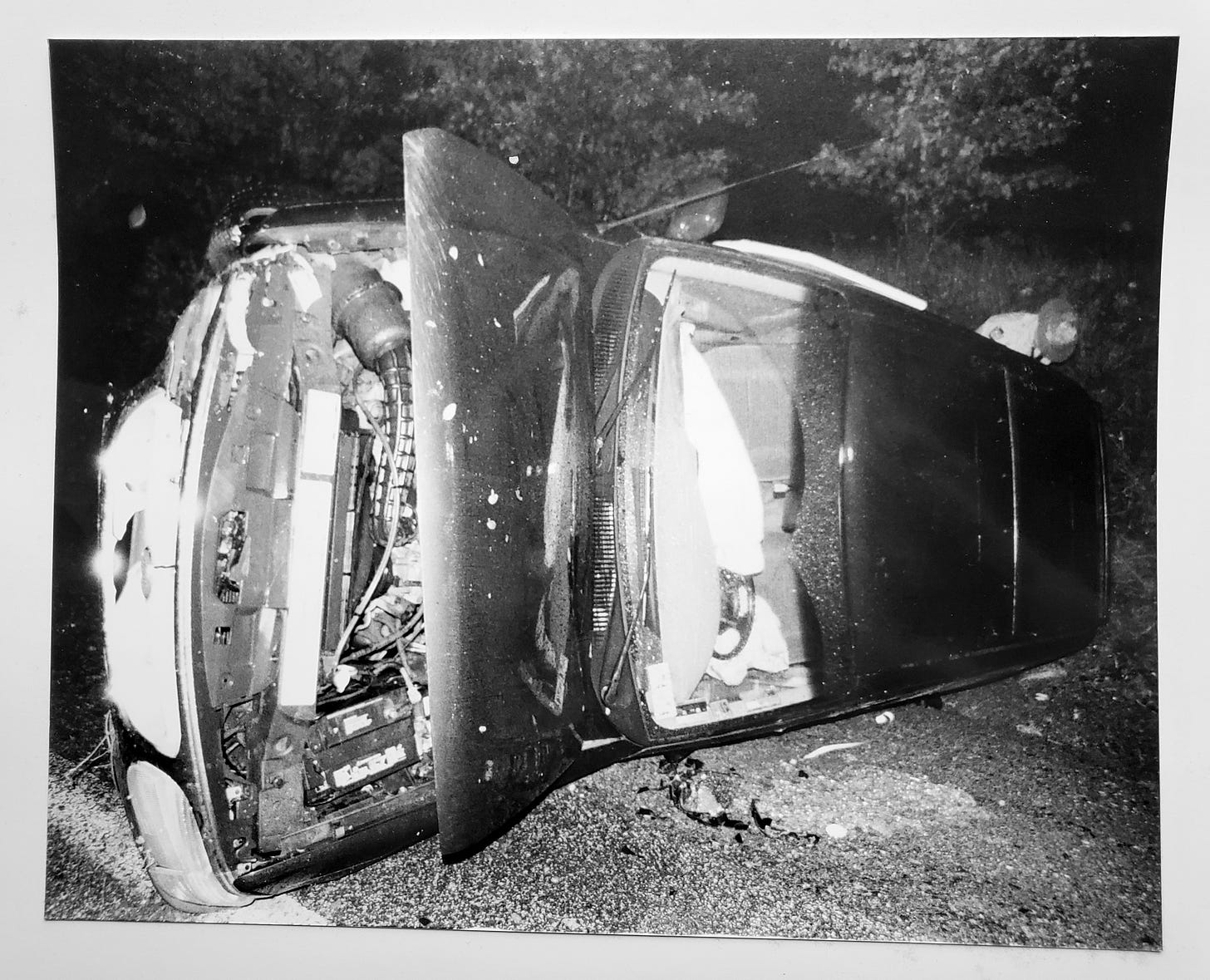

The first time I crashed, I experienced a whole series of incidents and remembered them. But this time it happened in the blink of an eye. I don’t even know what I did wrong. The car was totaled, torqued out of shape, but of course the stereo was still playing. This time I had been listening to Girls Against Boys’s first release on Touch and Go, the vaunted Venus Luxure No. 1 Baby. It was good music for keeping alert. Like last time, though, the first thing I did when the violence stopped and the car came to a halt was turn off the damn stereo. Only this time, I had to reach up to press the button because the car was sideways and the stereo was above me. It felt so insulting to be hearing that music again, again after spilling off the road and nearly dying. But this time I would react not with anger but with sadness — although, before I could react at all, I had to find a way out of the car.

The vehicle had rolled onto the driver’s side, so to get out of it I had to climb up out the passenger door window, which fortunately still rolled down. All the rain now was coming straight down into the car, but what did it matter anymore? My mother’s nice big car, which she liked so much, the parting gift she received for twenty-four years of broken marriage, was wrecked. Thankfully there were no other motorists around me when I crashed, but it wasn’t for lack of end-of-weekend traffic. Providence just arranged it that way. After being stunned for a bit, and after emergency services arrived, it felt natural to defend myself from the trauma by hiding behind the voyeur’s lens. One of the first responders retrieved from the car my camera bag for me, which wasn’t hard to find. On black-and-white film I documented, among other things, the traffic back-up I had caused. But when I shot the following image, I did not see the man walking by the road, being blinded by the headlights in the rain.

Discovering the silhouette only in the dark room, I then superimposed it on another image to make this:

The life so well illustrated by the likes of Girls Against Boys and Low was leading me here. The potential for death was real and present. Thanks to the airbags (and, of course, the seat belt) I hadn’t a scratch, but it was another power that was preserving me from destruction in this highly sophisticated, tragically flawed piece of modern engineering that betokened my parents’ broken marriage. Back in the mid-’90s, some may remember, there was a trend of Ford Explorers tipping over. They had designed them too top-heavy. Ford would correct the problem eventually, but my mother’s model was the last one before the correction. More crucially, though, the tires were sorely underinflated — illegally so, I was informed by the state trooper. I was a seventeen-year-old kid who had never been taught properly to check the air in the tires. My mother didn’t pay attention to such things. I had hydroplaned off the road driving full speed on the interstate. It’s a wonder I survived. (Parents, please teach your teens to check the tires.)

My mom couldn’t come get me. I just wrecked her car. That meant my dad would have to be pulled away from whatever he was doing that evening and drive all night to Virginia and back, picking me up and dropping me off along the way. We didn’t know where in Pittsburgh he lived at that time, not for the last three years. The woman for whom he left us, whom prior to that he had been seeing for two years behind our backs, wanted it that way. He would show up every now and then, to take me out to dinner, or give me a few driving lessons when I had my permit, but we didn’t know where he lived. By calling around we were able to get a message to him, about where I was and what he needed to do, and we heard back that he would come. That Sunday was a big sports day, capped off in the evening by Game 7 of the World Series. Beloved former Pirates manager Jim Leyland had a chance finally to win a championship, albeit with the Florida Marlins. My dad was with a bunch of friends watching all the games, so that’s what I was tearing him away from.

Meanwhile, there was no trip to a hospital required of me this time. Instead, as a place to wait, a policeman took me to the truck stop at the nearby Town Hill exit. As I sat down, mourning my parents’ bitter separation and my own role within it, I looked up next to me and saw just the saddest, stupidest thing. My mother’s favorite children’s book that she would read to us, she would always tell us, was Home for a Bunny. It was about a lonely homeless bunny looking for a mate. In the end, after many failures, he finally finds someone to be with, “And that was his home.” Directly across from where I sat down in the truck stop, there was a stand of Little Golden Books for children, and right in the middle, staring me right in the face was Home for a Bunny. Sometimes, the way God scripts our lives can be so stupid and overwrought, the symbolism so obvious and on-the-nose — like, where’s the subtext, God? I couldn’t say if we still had the book somewhere, so I bought the copy of Home for a Bunny from the truck stop to give to my mother in exchange for wrecking her beloved SUV.

I don’t remember speaking much with my father in the couple hours’ drive to the cows in Virginia. We caught word on the radio that the World Series turned out favorably, so that was good. He waited until he dropped me off at the door to give me a word of paternal rebuke. This was the second car I had totaled in the span of four months. He said he wished I would start to take more responsibility in my life. That was it, and he left. The irony was not lost on me for a moment. I was so unimpressed with this man. This was the man who, upon leaving his wife and kids, only revealing then that he had been cheating on them for two years, sat down with his legal pad and wrote a letter to my mother listing all the ways he felt that she had failed him in their marriage. The man whose kids didn’t know where he lived. The man who wasn’t around to teach his son how to shave, or, say, check the air in the tires. The man who when he was around, before he had left, dominated the house with the fear of his vicious temper, throwing childish tantrums at the drop of a hat whenever he didn’t get his way. I was so relieved when he left.

And me, did I need to take more responsibility in my life? Yeah, I needed to take more responsibility in my life. But it’s the Hamlet situation: when you need to set things right and you haven’t a father around to teach you how. As the play will teach us, those who populate the life of such a young man are in imminent danger. Well, a year later, in Boston now, in my first semester of college, I encountered intelligent peers who had more expansive musical tastes than I. I had cause to question, Why did I like the music that I did? What value was this identity I had formed with all the bands I had loved in my high school years? I began to dissociate rationally with the music I had identified with, even if the melodies and rhythms irrevocably marked the lower recesses of my soul. Then, that same semester, a year and two weeks after my second car crash, the Lord led me into an Orthodox Church, and my Hamlet situation began to be resolved. It was stunning to me how, as a young convert, I suddenly lost interest in all the music that I had previously identified with so closely. Yes, even Low. There were demons in Low’s music, saying, “Don’t be afraid of the dark,” and I heard them for what they were. I saw despair for what it was, which is pride, a kind of left-handed version of pride, equally as self-centered, and I renounced it. Girls Against Boys, for their part, represented the war wrought between desire and control, and by the grace of God my mind was no longer held captive in their shadows.

Sometime in the next couple years (I forget the context), I was driving alone on some road trip, listening to some music on a whim just to occupy my thoughts. Right then, it occurred to me that, though I appreciated the music, I wasn’t compelled to listen to it anymore. I turned the stereo off mid-song and in the succeeding silence felt a rush of relief and enthusiasm. I was free. I could listen, or I could not listen. And now I had something better to do than listen. I could pray.

In time, over the years, I’d find cause to return to old music here and there and remember what it meant to me. Music is at worst a collaboration of humans and sin, or humans and demons, and that which is human in that mix is always worthy of redemption. The very passions of desire and control are meant to be redeemed as converts to the cause of virtue, yearning for that which is good and protecting it from that which is evil (of course, I’ve written plenty on this topic already). If I can manage, while having the rhythms of Girls Against Boys encoded in my musculature, to allow graceful virtue to order the activity of my soul properly, according to the Lord’s commandments, the patterns of that music and the feelings they induce can be redeemed. They can find their proper context and be purified of their corrosive influence. Amazingly, I’m even free to listen to this music again without threat of harm — provided that, in context, it’s expedient so to do.

One thing I have never done again, though, not since that Sunday night in late October 1997, is that I have never... ever... listened to Girls Against Boys while driving ever again. Once was a fluke. Twice? No. No, no, no. Never again. There will not be a third time. It’s not even a superstition thing! I have not again been in any kind of accident like the ones I’ve described here, but if I ever were, I need to make absolutely, 100% certain that I am not listening to Girls Against Boys when it happens. And the only way to make sure that that’s the case is never to listen to them while driving ever again. Let it be any other kind of music playing when the car rolls to a stop and the violence ends. Just not Girls Against Boys. Never again. The end.

I think this is my favorite genre of yours. Not sure what to call it...the "redeeming the music I used to like and the confessional story telling mode I'm using to write about it" style? Instructive and enriching as usual, my friend. I never would have thought to make that Degas comparison. Also truly remarkable story.

Please write about anything, and I'll read it. This is remarkable. Don't need to say much more. I'll leave it apophatic.