I’m sitting down to write for the first time in weeks. Since my last proper journal entry (not the quick video I just threw up last Friday), life has swerved away from me, taken a turn towards something ominous. I’ll fill you in about that here, but first, while I have your attention....

I’m searching for a female voice actor for a meaningful project: My friend Weston Adam and I have recorded eight long-form conversations on cinema that we plan on turning into a podcast. This is something that has been long in the works, because we’ve hoped to make something grand of it. The plan is to couch the conversations about certain movies — a couple of which you will have heard of, but several obscure ones you probably won’t have heard of — in the fictional setting of a future dystopia in which cinema no longer exists. Civilization as we know it no longer exists; people live isolated in pods floating high in the atmosphere with all physical needs attended to by technology, but with no reason to live except to figure out how they got there and what they’re supposed to do about it. To that end, using sophisticated electromagnetic telescopes, they mine thickly layered pulsar fields surrounding the planet to find old audio patterns that have either shrunk or expanded outside the radio spectrum, signals that reflect the world as it last was before everything went wrong.

The role we need to cast is that of the female Archivist who has skillfully mined and refined the audio of our lost conversations and is presenting them to other pod-dwellers like herself with introductory and concluding remarks. What we’re attempting to do is make our conversation more interesting and palatable for those who haven’t seen the movies we’re discussing. The Archivist hasn’t seen any movies, inviting the listener to think more broadly about the ideas being raised. My friend Weston is a musician and has scored the entire conversations with background audio with which the voices were mixed in the pulsar field where they were found. The hope is that each episode would be interesting to listen to even if you didn’t know English, let alone the movie being discussed. Finding the right person to fill this Archivist role is essential because so much of the fictional context will need to be conveyed succinctly in her brief performances. The actor would also be invited to collaborate in scripting what she says, but if whoever has the right voice would prefer that it all be written for her, we can go that route as well. I’m casting a broad net here. If any of this interests you, or may interest someone you know, please do not hesitate to reach out to me. My email can be found on this journal’s About page.

As for the Journal, I had plans of what to do since my last Substack post. First, I was going to write a Symbolic World article, something I haven’t done in (gasp) two years. Then I was going to write a second Journal post for the month of May. Optimistically, I had time. That first week, I got sick and couldn’t get too far in the Symbolic World article, which I still hope to finish some day; I’ve long planned on writing it. By the time I felt better, though, I had to switch attention to getting out that second post for the month of May. I had barely begun when my mother had a health crisis that has resulted in her being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, an excruciating disease, which constitutes my mother’s worst nightmare. She was hospitalized for a week and a half, and it has been an ordeal navigating the healthcare system just getting that diagnosis. More than once I’ve had cause to think about the classic post-communist Romanian film The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, if you’re at all familiar with that. So understandably my attention has been otherwise delegated. I apologize to my subscribers all the same, as well as to anyone who has reached out to me and hasn’t heard back. The last two summers I’ve had a devil of a time being productive. Early signs suggest I won’t buck that trend this year, but we’ll see. Life’s a constant battle.

And as soon as my war for productivity makes headway, I believe I’ll have to begin concentrating more exclusively on my octave book. The gestation time on this large project has just been too long. If I’m ever to finish it, which I believe I need to do, I’ll have to begin sacrificing other things that I also want to do. That would not mean sacrificing posting on Substack, but free subscribers might be seeing less of what I’m up to. Do know, however, that whenever I send out previews of paid posts to free subscribers, I’m not just spamming for subscription dollars. I value the space in your inbox and am not trying to clutter it. On such articles, I try to set the paywall barrier low enough that there’s still something substantial available that free subscribers would find worthwhile. If ever I write a paid post in which I can’t functionally do that, I just won’t send out the previews.

Again, though, if I ever bank enough paid articles that interest you, please consider signing up for a month and sending eight dollars my way. The price point for subscription was chosen with this behavior in mind. Am I going to get a year’s subscription for Disney+ just to watch Andor? Hell no. I will get the minimum of one month’s subscription, watch Andor — because Star Wars is suddenly brilliant now? when never before in my estimation has it even been good? this is a very strange development — then maybe, if I have time, rewatch David Lynch’s The Straight Story, and cancel that thing. Don’t worry, though: if you stop subscribing to my Substack after one or two months, I won’t interpret that action as expressive of the way I feel about Disney+. I know that I have a limited amount of content and that I need to write more.

So! A moment has generously been provided for me here. About that “writing more” thing...

Prologue

How one performs in a crisis is one thing, and how one performs over the long haul is another. The parable of the two sons in Matthew 21:28–32 is relevant here; how you react in the moment when father comes calling for your labor is one thing, and how much labor you actually end up doing in the long haul is another. These are two different things, but how they interrelate is an ever-present topic of pondering for me. How my mother behaves when cancer comes calling unannounced and under cloak — when an unknown mass at the head of her pancreas blocks the bile ducts in her liver, causing her to itch all over and portending much worse things to come — is one thing. How she comports herself once a stint is inserted to relieve the blockage, once she gets a diagnosis and faces months of chemotherapy hopefully to shrink the tumor, allowing for an especially strenuous Whipple procedure to remove the cancer, followed by weeks-to-months of recovery plus months more of chemo, hopefully to cure the disease, is another. That’s the pattern of crisis and long haul fractally present within the crisis which lies at what might be the end of my mother’s life (hopefully there’s a bit of long haul left to go).

There are more general examples. In Christian and post-Christian settings where some degree of autonomy is granted to the individual, everyone in their youth faces a crisis of decision. Depending on the person, these crises may be quick or slow to come, but they hit everyone eventually. Indecision itself constitutes a decision. And of course, it’s not just one decision but a constellation of decisions, all of which take place in the same general period of one’s life. Then for the rest of one’s life, we face the long-haul consequences of those decisions, good and bad. We constantly carry the burden of our bad decisions, and — what’s even harder — we constantly are called to be under obedience to the good decisions, to honor them with a faith that lasts forever. A Christian who marries young may have opted never to know the blessing of living in obedience to a monastic elder, but once one is married that’s hardly needed. Each such spouse’s own abbot or abbess is their own early-twenties self who has assigned them the lifelong obedience of being faithful to the betrothed of their youth. Such a youthful wedding can be an unbelievably glorious affair, cathartic for an entire community. It’s a crisis hopefully in the sense of a eucatastrophe. The long-haul marriage that follows, however, may appear at times desperately void of that glory and a massive test of faith. But the discovery to be had by the faithful end of that long haul is that its catharsis, though less spectacular, seemingly more mundane, is in truth more glorious because to it have been added layers of illumination and perfection previously unimaginable.

The Age of Innocence

I have always loved Christian art that captures this dynamic of crisis and long haul (speaking of “Christian” art in a civilizational sense, not the marketing genre). My favorite movie The Age of Innocence, the 1993 Martin Scorsese adaptation of the 1920 Edith Wharton novel — am I actually going to write about it now? I have written so little about it because it overwhelms me so much. I will say a little. The story has two halves that correspond to this idea of crisis and long haul. The first half takes place over a short period, when young lawyer Newland Archer endures a quietly disturbed engagement to his future wife May Welland in the high society of 1870s New York City (the setting of author Wharton’s own childhood). The second half takes place over the long period of his marriage. The bifurcation causes what seems to be the story’s fiery emotional climax to take place not even halfway through the running time. In the movie it comes about an hour in, after which there’s more than seventy minutes left to go (the book is similarly divided). There’s almost the span of a feature-length movie that takes place after the climax. Well, I first fell in love with this story when I saw it on cable at age fourteen. In later years I might have identified this climactic scene, where Newland confesses to his fiancée’s cousin Ellen his passion for her, as something of a chiastic center, but as a pubescent kid gaping for wisdom (and unable to understand the Bible), it occurred to me that the early climax was a way of making the whole movie about that long haul occurring after the moment of youthful crisis comes and goes. The ending of the final act, then, doesn’t hit the emotions the way the end of the first act does. No, it goes so much deeper. And then the emotions rise to meet it and become something so deliriously beyond anything they ever were.

This is the very shape of life and the challenge we face in this world: can we find meaning in the aching tedium of the long haul? When artists who work in a sequential medium place their climax in the early going, they get to ask the profound question, What happens after the catharsis? What’s it like to experience something that throttles the soul so viscerally, but then to go on living afterwards for years and years and years? Artists don’t ask this question nearly enough, possibly due to lack of spiritual maturity. Finding meaning in the long haul, past the point of crisis, takes a lot of wisdom. Catharsis literally is a purification, so in a sense it’s just the first stage of the spiritual life, with illumination and perfection to follow. What does meaning look and feel like at those points? Artists, particularly those who live the life of the senses and are prone to solipsistic indulgence, don’t often get that far. Edith Wharton wrote plenty of excellent literature before 1920, but it took the traumatic experience of the Great War, when she served zealously in France performing many charitable operations, for her to be able to empty herself, look back at her life with illumined eyes, and create her spiritual masterpiece.

Low’s The Curtain Hits the Cast

As I said, I have loved that story, The Age of Innocence, since first seeing the movie as a fourteen-year-old. Then I was sixteen years old in 1996 when Low’s album The Curtain Hits the Cast (YouTube, Spotify) came out, and I found there a similarly shaped sequence to the songs. There was what appeared to me an early climax — much earlier, in fact, than the halfway point — followed by a very long haul indeed, more closely mimicking life’s timeline. Low, as was their minimalist wont, did it all differently, though. I perceived they arranged for an early climax, but it wasn’t a scene of fiery unleashed passion. It was a quiet moment of reflective truth — the concluding line of the fourth song, “Mom Says,” set apart from the rest of the lyrics like an apocalypse: “Mom says... / we ruined her body.” This is catharsis in the tragic sense, even if it’s the kind of thing a woman (a loving woman, at least) tells her children in a comedic tone. The irony, ah, the irony is so piercing! David Lynch calls this an eye-of-the-duck scene, the moment or place within a work of art where attention and perception are perfectly gathered, around which the rest of the composition appears arranged as though in service to it. (My “Eye of the Squirrel” video last week is a reference to this idea.)

In the sequence of The Curtain Hits the Cast, this moment, though quiet, devastates as efficiently and as tragically as the scene where Newland Archer confesses his passion for Countess Olenska. And there are a full eight songs after it, starting with “Coattails,” a sweeping seven-minute piece that carries the listener away from that eye-of-the-duck moment as if in exile from a homeland. “Coattails” enforces this album-wide structure by itself also having this structure. For its own eye-of-the-duck moment it features a single lyric, “He rides on coattails,” repeated three times beginning a minute and a half into the song and then never again for its long duration. The exile continues with the next song, the beautiful “Standby,” which literally asks you just to wait. And then the next song just festers in the long haul, “Laugh,” a slow, bitter, sad nine-minute wallowing in the irony of its title (“They’re gonna laugh / behind your back”), a remembering of the irony of “Mom Says,” but lacking all of its ripeness. Low does not look away from how sour the long haul can be.

The next song, “Lust” (which of course I’ve written about before) changes the trajectory of the album and sends it towards its concluding apocalypse, “Do You Know How to Waltz?” Low, in these early Vernon Yard recordings, were purposefully inverting the style of ’90s alternative rock music around them, and they equally invert the pattern I’d like to be talking about here. The pattern is there, that is, but because they’re asking you to listen to their music in an inverted way, the presentation of the pattern too is inverted. The early climax is an eye of quiet in an ocean of quietness, and its conclusion to the long haul, contrarily, is tempestuously loud. “Do You Know How to Waltz?” sends the listener on a long, attention-grabbing, fractally ascending three-chord swirl of industrial distortion and dissonance. It externalizes the profundity of the long haul’s conclusion, just as “Mom Says” internalizes the spectacular early crisis from which the rest of the album precipitates.

Arvo Pärt’s Te Deum

A better example of what I’m talking about, and an even better inversion of the whole of modern music, is Arvo Pärt’s Te Deum. When I discovered this composer in college as a late teenager, this was the first piece I heard, and I recognized in it the same pattern I adored in The Age of Innocence. In the classic 1993 Tõnu Kaljuste recording for ECM, the early climax comes at five and a half minutes in, erupting as a eucatastrophe of overwhelming sweetness. “Pleni sunt caeli et terra majestatis gloriae tuae,” the choirs sing with pure tonality and exhilarated melody, “Heaven and earth are full of the majesty of Thy glory!”

And when it’s over, there’s still more than twenty-two minutes left to the piece. There are other peaks to come in this mountain panorama of music (as Pärt himself envisions it), but none so memorable to the casual listener for just how intensely sweet it is. Ah, but then, this isn’t music for casual listening. For those who invest themselves in the journey, the profundity of beauty to be found alongside exhaustion and humility at the end of the long haul — I speak especially of the “Miserere nostri, Domine, miserere nostri” sung towards the end by the male choir, joining themselves at last to the eternal bass drone heard throughout the piece — is so, so much more glorious than the sweetness of youth. Indeed, to put it in terms apposite to The Age of Innocence, which do you think is to be valued more: the pleasure of the wedding night, or the son and heir that appears subsequently therefrom?

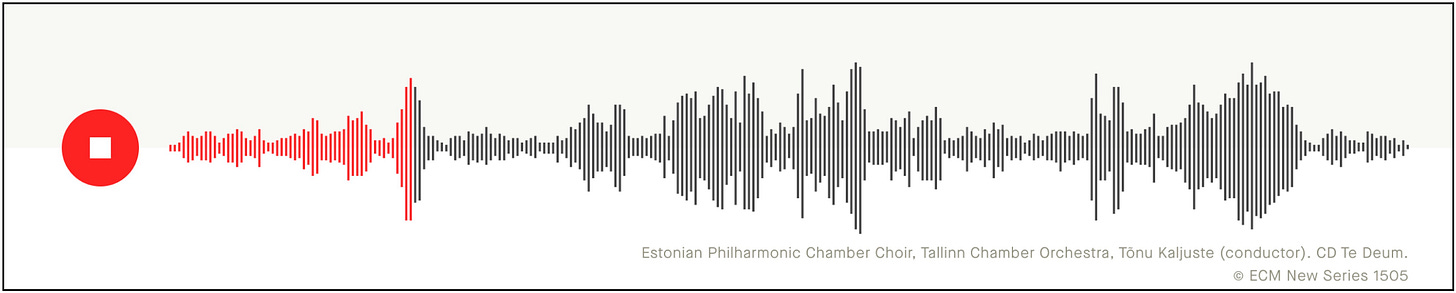

Here’s a visualization showing at which point the early climax comes within the full range of the twenty-nine–minute piece, from the audio player on Arvo Pärt’s website (which page also includes the hymnal text in Latin and English, if you’re interested):

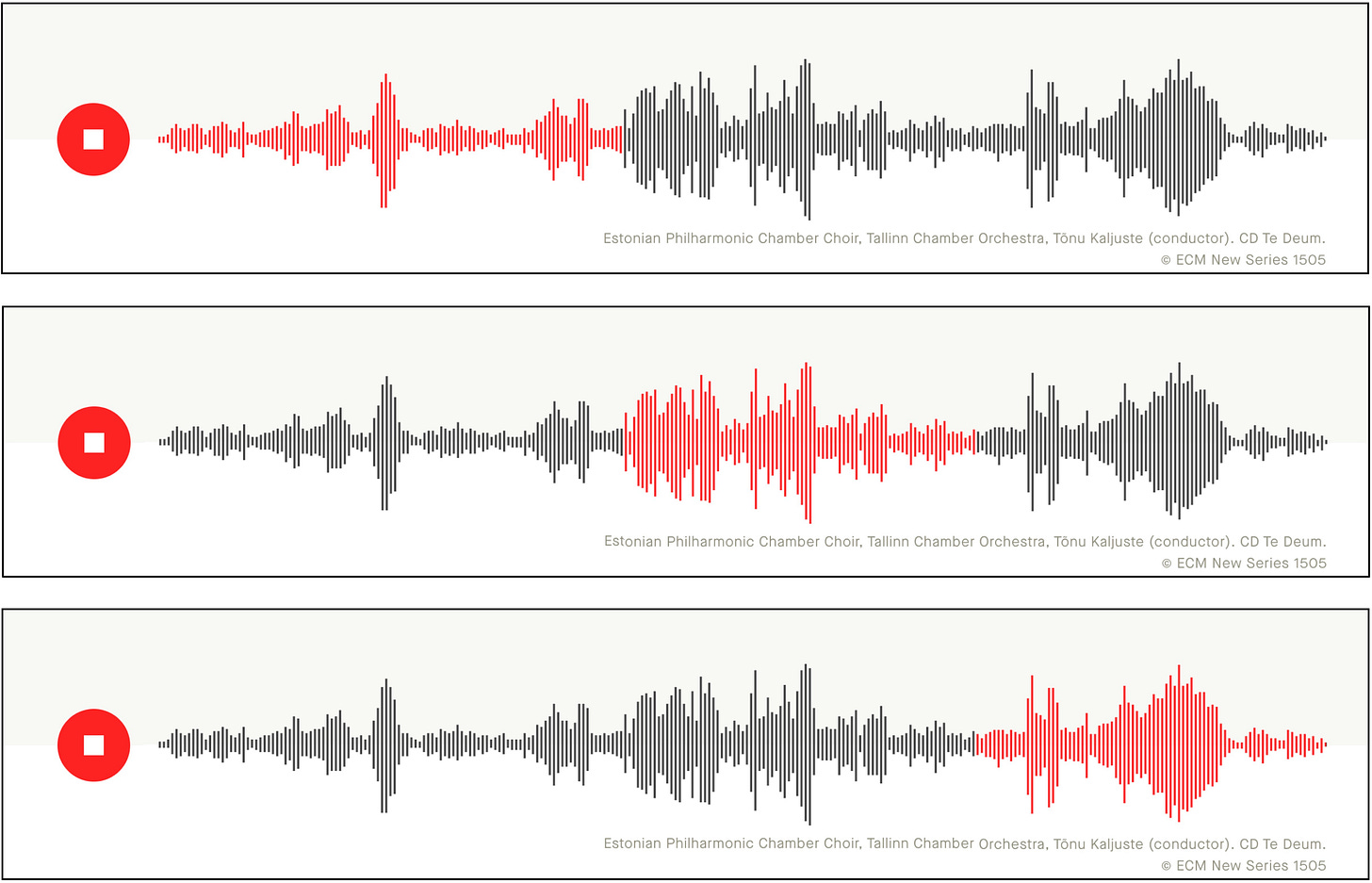

It’s actually not even the end of its section, but rather the chiastic center. The whole composition flows together as one, but is structured in three parts, as highlighted separately here, part one, part two, and part three:

(Part two begins with the boisterous “Tu rex gloriae,” and part three begins with the piano-punctuated “Per singulos dies,” per the description of Paul Hillier in his monograph Arvo Pärt [Oxford, 1997], p. 144.)

This is the archetype of the pattern I was sent out in search of by The Age of Innocence. Actually, The Age of Innocence’s shape is just part one of this sequence. You see the highlighted part one of Te Deum, with the unbelievably sweet climax spiking in the middle? That’s a good simulacrum of The Age of Innocence. And then Pärt, in his worship of God, in his glorification of Christ, goes stages beyond that, adding the forms of illumination and perfection to the form of purification (catharsis). The “Miserere nostri, Domine, miserere nostri,” “Have mercy on us, O Lord, have mercy on us,” at the end of this piece, as all the bass music swells to capacity, infused with the spirit of the wind harp that has provided the drone since the beginning, creates a portrait of the Christian soul that may contain the sensory ecstasy of the early climax, but that expands far beyond it as well. There is spiritual ecstasy up in those hills, more than just the practice of the virtues proper to the soul, which raise us beyond the life of the body. In Christ we experience the life of God, beyond soul and body, beyond heaven and earth.

Stereolab’s Instant Holograms on Metal Film

Even before my mother’s sudden hospitalization, I was sent into these thoughts about crisis and long haul by recently released music by some older artists who were formative to my youth. Last fall, Kim Deal of the Breeders and the Pixies dropped a solo album, Nobody Loves You More (YouTube, Spotify), that feels every bit the follow-up to Last Splash that we never got. It even sounds like it was produced in the nineties (if re-mastered for streaming). To see a Gen-X rock musician in her sixties emerge from the long haul of life and create something as excellent as ever is so strange and inspiring to me. I don’t remember Boomer musicians having arcs like this. Rock music had always been the milieu of youth because it’s generated from the body; menopausal artists were out of fashion and creatively spent. Neil Young was always the exception, but now I see several like him who keep on rockin’ in the free world, creating music that feels vital even as the illusion of the free world grows dimmer and dimmer.

And now, just recently, Stereolab have dropped their first new album in fifteen years, Instant Holograms on Metal Film (YouTube, Spotify). I loved Stereolab as a teen in the nineties, especially the album Emperor Tomato Ketchup, but also Dots and Loops. A couple weeks ago, I used their song “Percolator” in our last Sunday school class before summer to teach the teens about the purpose of repetition in music, showing how Stereolab build songs vertically by looping little musical ideas around and around on top of each other — and then actually relating this to psalms and hymns of the Church like the Polyeleos (Psalms 134–135), the Song of Miriam, and Psalm 118 and the Lamentations for Holy Saturday.

See the vertical spiral on their album cover there? That’s like how their music works. It’s a departure perhaps from the classical Western tradition, which puts more emphasis on the horizontal, but, for all their use of synthesizer technology, Stereolab find themselves returning to some ancient patterns of music that are common in forms of ritual worship. They’re common because they’re natural. The sun goes up and down, the weeks repeat one after the other in a circle, the moon goes full and empty, the sunrise goes north and south as the seasons turn through their cycles. We pray every evening and morning, we gather in church every weekend to celebrate the Resurrection, and on all the feast days in all the years throughout our lives. By continually returning to these singular moments in the life of the Body of Christ, we go deeper into them, we expand upwards and outwards, ever encompassing more and more human experience. As with even a simple song that is composed according to these patterns, the cumulative effect can be transcendent.

And it’s human. For all their use of electronic technology, developing their sound from the nature of the Moog synthesizer, Stereolab’s music is beautifully human. As civilization nears the end of its long haul, and we are swallowed and digested by our tools, it is so vital to hear these precious human sounds coming through the machinery. Sure, compared to Arvo Pärt, Stereolab may seem a massive step towards the madness of idolatry (their leftist ideology sure doesn’t save from the abyss of meaninglessness the way ancient Christian hymns do), but creating music in a world where Kraftwerk and their influence had already existed for decades, to say nothing of electronic dance music, Stereolab appear in history like apostles of humanity to a nation of sleeping cyborgs. The drumming of Andy Ramsay gets to me especially. Since the days when I came of age, there’s been so much quantizing of beats, so much music with the life programmed out of it, I feel so exhilarated to hear Andy Ramsay’s live human drumming in clips like these:

He uses the motorik style of drumming that creates a steady machine-like beat, but it’s audibly a human operating the machine — a machine itself created by a human. It’s entirely natural for humans to create and use machines. It’s just unnatural for us to serve them as idols and be ruled by them. I perceive in these classic tunes from Emperor Tomato Ketchup attempts at creating icons of the proper relationship. The follow-up album Dots and Loops went more computerized, more ethereal, less grounded and earthy. I still liked it but less so. I lost contact with the group after that; they made more albums but to less acclaim.

And now, all this time later, they drop Instant Holograms, and they are at the very top of their game:

“Greed is an unfillable hole.” “We can’t eat our way out of it.” With all our troubles regarding the oikos, be they economical or ecological, we keep trying to solve them with increased appetite and the numbing of reason. But “The numbing is not working anymore.” The fault is in our desires. At this point in my life, with so many reasons to despair for culture and politics, to hear new music from Stereolab, and for it to be this alive — it feels like fruit from the long haul. But it also feels like it’s being provided in order to prepare us for dark labor pangs ahead.

Gillian Welch and David Rawlings

So there’s Stereolab, on one hand, and then there’s Gillian Welch on the other. Yeah, just imagine those dark labor pangs have come and taken all our electronic synths away. What you have left is what Gillian Welch has made her life’s study: the music that lasts. This was another college discovery of mine, circa the 2000 movie O Brother Where Art Thou?, which soundtrack she contributed to, but I heard of her through a friend — back when she only had the two albums, Revival and Hell among the Yearlings. I was already in love, but then 2001’s Time (The Revelator) came out and I was blown away even further. This is vital art, like Arvo Pärt, deeply traditional but entirely contemporary.

My dad watches Stephen Colbert, a program I find deplorable, but one night he calls me and says Gillian Welch is going to be on. I have to come down to the house anyways, so I time it to catch her song on the TV with my father. It’s from her latest album Woodland, which came out last summer. I listened to it then, but then forgot to go back to it, which was a mistake. It’s amazing. I have been jaded about my nation’s culture for so long. To hear music this real, this good, on national television, to witness my people championing something true and beautiful after so many lies and decrepitude — it moves me to tears.

And David Rawlings, her musical partner — I have been listening to these two play music together for a quarter of a century. The way Rawlings picks notes on his guitar, it’s as recognizable to me, and as dear to me, as Gillian’s voice. How does he do it? The guitar is not exactly a new or uncommon instrument. Folk and country are not untrodden genres. How is it that I can recognize his playing? He and Gillian have enriched my life so much. I love so much of their music, all the albums I named before plus 2011’s The Harrow & the Harvest especially, that I can’t name any one favorite song. I couldn’t even name just five favorite songs — or ten. There are too many essentials. One lyric, though, that strikes me as relevant to my current theme is from “The Way It Will Be,” a song off of The Harrow & the Harvest, but which was written as early as 2004.

It’s a song of grief and mourning over love betrayed and hierarchical breakdown, with the culprit being someone at the top of the stair who refuses to share glory. And in the first verse there are the lines, “Gotta watch my back now that you turned me around. / Got me walking backwards into my hometown.” That last line is so evocative. One’s hometown is one’s country, where one’s from. It should be a place where one enjoys freedom and familiarity, but she has been restricted there and at the same time alienated from the place she knew. Everything’s backwards. That’s the way I feel in my hometown, my home country, my home planet, and I know a lot of other people feel the same. “You said it’s Him or me,” Gillian sings to the betrayer above her (capitalization mine). “The way you’ve made it, / that’s the way it will be.”

We’re collectively in the climax of the long haul; that’s the chill I feel in the air. It all seems so culturally inglorious compared to the highs of the past, the highs of youth. But when you scrape away the muck, all the copies of copies and computerized regurgitations, you can still find in places a beating human heart created by God, still singing eternal truths that never change. Gillian Welch and David Rawlings are a perfect duo for these end times. Their vocal ranges are the same, and often his tenor harmonies cling to her alto melodies from above not below. In “Howdy Howdy,” the final track on Woodland, it’s the man asking the questions and the woman giving the answers. Everything’s upside down as in death — but if configured right, as in a Christian context, a song of resurrection can be signaled thereby.

As I drive back and forth over the mountains between my father with Parkinson’s in Western Pennsylvania and my mother with cancer at hospitals in Virginia, “Howdy Howdy” is the tune I hear hanging in the hills like a fog. “The best part’s / where ‘one’ starts / and ‘the other’ ends” is such a fine lyrical icon of resurrection, of life overcoming death. This is what constitutes new art in 2025: old souls, tired, beaten down, but not defeated, testifying to divine spiritual unity that is for always, lasts forever, and is everywhere present, even in the crooked Eastern Woodlands of my American home.

“The devil he’s / blowin’ reveille / and we ain’t got long.”

This was incredibly beautiful. Thanks for sharing. I feel this is the kind of article that shakes me in such a way that if I allow it to act on me, some rotten fruits will come off, so that I can concentrate on the real gifts. IDK how to say it otherwise.

You and your parents are in my prayers.