Psalm 80, the chiastic center of the Psalter

For my 80th post on Substack, a shout of lament-filled joy

In The Shield of Psalmic Prayer, the late Subdeacon Donald Sheehan, university professor, translator of the Psalms, published poet, and above all a man of prayer (whom I’ve met and admire), identifies Psalm 77 as the chiastic heart of the Psalter (that’s Psalm 77 according to the Septuagint numbering, which the Orthodox Church uses and I’ll be using throughout). Unfortunately the book, compiled posthumously from notes and essays and sundry writings, gives no clear explanation for this identification, only implying that it was discovered based on the sixty-two times blessedness is mentioned in the Psalms, according to his count. Professor Sheehan derives his emphasis on blessedness from St. Gregory of Nyssa’s exquisite On the Inscriptions of the Psalms, where that father identifies blessedness as the aim of the Psalter, focusing especially on how Psalm 1 begins. But in that same work, St. Gregory lays out the five-part division of the Psalter — the psalms that end with a doxology and the phrase “So be it, so be it” all mark a section break, namely Psalms 40, 71, 88, and 105 — according to which Psalm 77 is just the sixth of seventeen psalms in the central third section. Looked at this way, it’s unclear how Psalm 77, with five psalms before it and eleven psalms after it, could be the chiastic heart of its own section, let alone of the whole Psalter.

The seventeen psalms of the Psalter’s central section have rather Psalm 80 as their numeric center, their median. Now, that’s not a reliable way to locate the chiastic center of any biblical sequence according to its content (should it even be chiastic), but here it makes eminent sense. Eightfold patterns play a prominent role in the course of the Psalter. Sheehan knows this, as he divides Psalm 77 into nine eight-line stanzas, singling out the first, middle, and last stanzas as the frame of a chiastic structure. And of course, Psalm 118, which Sheehan writes about a lot, is an alphabetic acrostic of twenty-two eight-line stanzas. The number eight stands out due to the nature of the heptatonic musical scale and the fact that David was a musician and all the psalms are in fact song lyrics. Well, I believe the whole Psalter opens and closes with an octave of psalms, Psalms 1–8 and 143–150 (the first and last kathismata of the Orthodox Psalter). And in the seventeen-psalm central section, if you take Psalm 80 as the center, you’ll find exactly one set of eight psalms before it and one set of eight psalms after it, each of which conform to octave patterns in their content.

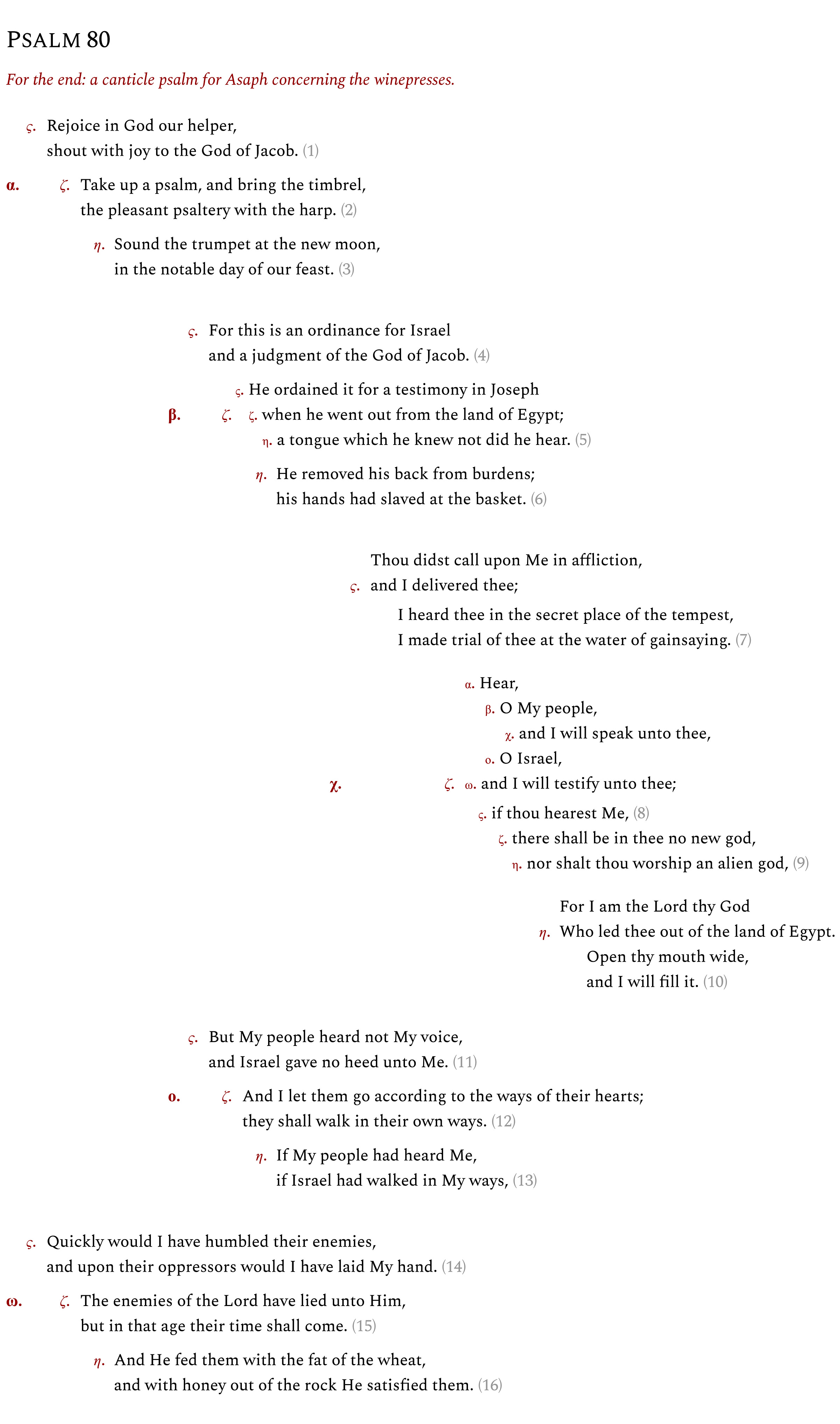

As you see in the outline from my website above, this arrangement yields both

a chiastic — what I call a “butterfly” — structure (two elaborate, symmetrical wings on either side of a skinny center), as well as

a linear, triadic 6–7–8 pattern (the Ϛ.–Ζ.–Η.), the kind we are accustomed to seeing in the middle of pentadic structures, one where the central sabbath operates as a liminal mediator between a human sixth and a divine eighth.

Also note the numbers. The numerology here is ridiculously meaningful, as the center of the Psalms with all their musical structure and octave symbolism is Psalm 80, climaxing in an eightfold climb from Psalms 81 to 88. So in a chiastic sense, Psalm 80 is the center of the Psalter, but in a linear sense, Psalm 88 is the pinnacle, as though the first, second, fourth, and fifth sections of the Psalter form the sphere of an onion dome, and this central third section serves as the linear tip.

If you look at the magnificent Psalm 88, coming on the heels of the unbelievably bleak Psalm 87 like a resurrection after death, you can see perhaps why it is an excellent choice for the Psalter’s pinnacle. But this is my eightieth post on Substack, not my eighty-eighth, so here I’ll be focusing on the Book of Psalms’ center, Psalm 80.

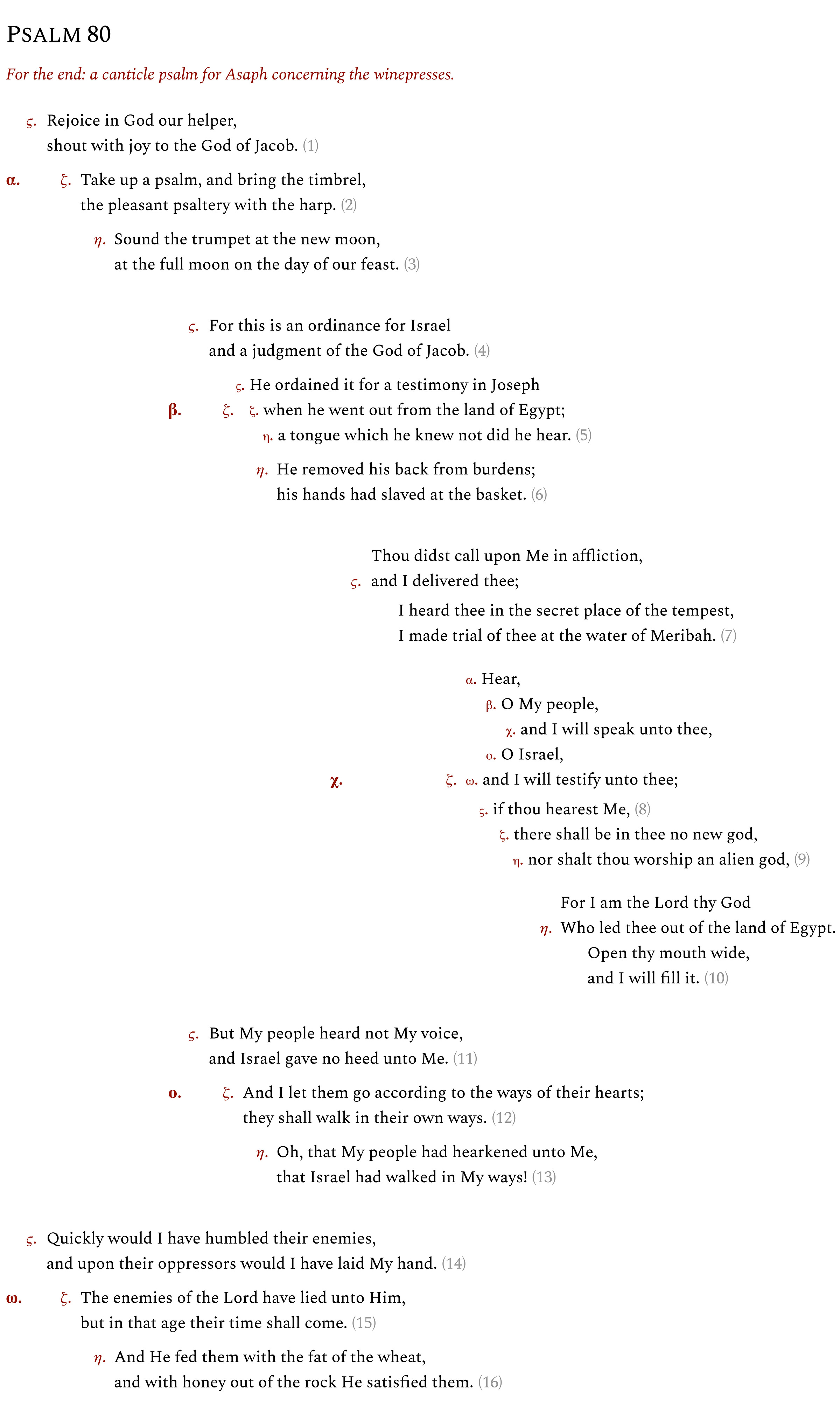

So the whole Psalm is a pentad of triads of (mostly) couplets, with the central section spreading into something more complex. This is the Holy Transfiguration Monastery translation from the Greek, which actually numbers the verses as fifteen instead of sixteen (combining what is here verses 8 and 9), which reflects better the 3 × 5 arrangement I understand the psalm to have. For others’ sake, however, I’ve used the verse numbering more commonly found elsewhere.

α. (vv. 1–3)

The opening call to praise God with open mouth and varied instrumentation comes on a new moon, the beginning of a lunar month, one on which trumpets are to be blown (in Hebrew, the shofar). These signifiers all point to the Feast of Trumpets (Yom Teruah) on the first day of the seventh lunar month (Tishrei), as prescribed in Leviticus 23:24 and Numbers 29:1. This feast initiates the series of holy days in the seventh month, notably the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) on the tenth day and the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) on the fifteenth, that is, on the full moon. Actually, when the third verse of Psalm 81 references the notable day of our feast, the Greek word for “notable” translates a Hebrew word which means full and is used to refer to full moons. Hence the Psalmist is crafting a couplet that refers both to the new moon of the seventh month and its fullness to come.

The autumnal setting, meanwhile, makes sense of the winepresses mentioned in the inscription. This psalm is for harvest time, and the inscription links it symbolically with the pressing of grapes for wine. (Psalms 8 and 83 also bear inscriptions “concerning the winepresses”.)

β. (vv. 4–6)

The second triad of verses combines positive and negative beta-typology like I can’t recall seeing elsewhere. In one line is mentioned the positive differentiation that occurs through the exodus from Egypt, and then the very next line alludes to the confusion of tongues that results from Babel, a negative mode of differentiation. At any rate, this confusion and slavery and burdensome labor is what Israel is being removed from and is being spoken of as if finished.

But here, you’ll notice, is the one place outside the central section where the triad-of-couplets pattern seems to be disrupted. There’s an uneven amount of lines. Either there’s a triad in the middle (as I have it), or there’s a triad on either side of a single line. For “He ordained it for a testimony in Joseph” follows the same iterative pattern as the first two lines, and “a tongue which he knew not did he hear” lists a body part related to a form of past vexation consonant with the next two lines (tongue, back, hands). I see it as a fractal. The central zeta-triad reflects the whole triad that is the beta-section, all hinging on the liberation from Egypt. As for why it’s here, why the pattern would seemingly be disrupted, I see it as a helpful indicator (by means of the fractal) of the ongoing pattern of triads. As you reach the fifth couplet in the psalm, you could be forgiven if you thought it perhaps was concluding a chiastic pentad of couplets. This little triadic fractal, however, pushes you forward to the sixth couplet with a different understanding. I think the psalm is just teaching you how to read it.

χ. (vv. 7–10)

But now already we’re at the center. And where the other sections consist of triads of couplets, here we encounter a triad of couplets of couplets (except the central couplet of couplets folds out into a couplet of a pentad and a triad — in other words, an octave).

This doubling-of-doubling structure in the center points to how the pentadic shape of the psalm relates to the fractal triad shape. The chiastic pentad is a triad — if you view it vertically. Alpha and omega form the outer layer, like a stigma-layer; beta and omicron form an intermediate layer, like a zeta-layer; and this chi-section plays the role of the climactic eta-layer. Its couplets are doubled because so are the couplets doubled in the lower layers, if you take beta and omicron together as one layer, and alpha and omega together as one layer. Maybe what I’m describing will take some work to understand, but once you see how this whole structure operates in all its dimensions — linear, fractal, chiastic, triadic, with an octave at its heart — it is so strikingly beautiful.

But let’s continue to go through the text linearly.

Right away in verse 7, the switch to first person jumps out. Here the Psalmist plays a prophet and channels the speech of God. The first couplet of couplets signals our purification. The waters of gainsaying is a literal translation of the waters of Meribah, where the Israelites, having been rescued from Pharaoh, yet needed to be proved for their lack of faith (see Ex. 17:1–7). They complained of having no water, so God had Moses strike a rock with his staff and bring forth water — “and that rock was Christ” as Paul insists (1 Cor. 10:4). Appropriately enough, the chi-section opens with Christ typology.

Verses 8 and 9 carry with them the feel of couplets coupling, but with added wrinkles. The repetition of “O my people” and “O Israel” lend a pentadic shape to the first couplet. And the second couplet — which reflects what at the head of the first couplet is the imperative to hear with, for its own first line, conditional hearing — sees its second line itself reproduce as a couplet, hence expanding the couplet to a triad. Now, in the Hebrew of the Masoretic text, there is one less phrase here than what the Septuagint translators have, such that the line here rendered “if thou hearest me” is enlisted to close the pentad, leaving after it not a triad but a couplet: “There shall be no strange god among you; / you shall not bow down to a foreign god” (RSV). Hence it’s not an octave but a heptad. Go figure, the eighth day has been whittled away for the sake of sabbath worship. But I trust the transmission of the text through its ancient Greek translation. Already this B.C. translation from the upward-gaping poetic Hebrew language into the more left-brain, philosophical Greek language foreshadows the Incarnation to come, when the God above takes flesh and walks among us. It’s this pattern of Incarnation which leads us to the advent of the eighth day on earth, taking us through and beyond the seventh day, not stopping us there.

Illumination by way of insight into this octave pattern comprises here the center and sabbath of the psalm’s chi-section — a psalm, I’ll remind you, at the center of the central section of the whole Psalter. This is no insignificant verse! Yet as the sabbath in a triad, it points beyond itself to what comes next. The seventh-day sabbath symbolizes the end of creation, the terminus; it is death. It is the day Christ lies in the tomb. The suggestion that there might be among us some new god (that is, a god which previously was no god), or that we would worship some alien god, expresses this death in its utmost form. These mortal realities are grammatically negated since they represent the sabbath and eighth day relative to their own verses, but they also operate as indicators of the eighth day beyond it, relative to the whole central triad.

“I am the Lord thy God who led thee out of the land of Egypt. Open thy mouth wide, and I will fill it” is to my mind the single most powerful verse in all the Psalter.

This is not merely the voice of the Psalmist praising the God of heaven and earth. This is the voice of God Himself, revealing Himself, naming Himself as once He did to Moses, as Yahweh. And it’s the voice of the Psalmist. This is the voice of God Incarnate as the Son of David. This is perfection, this is Theophany, and it is deliverance for us. The Lord is He who brought us up out of the land of Egypt. The Greek verb in that phrase, “led out” or “brought up”, is a cognate of anagogy. If you ever wish to learn what anagogy means, look no further than this verse. An anagogical reading of Scripture entails this leading up, or bringing out — out of Egypt, which is to say, out of our passions, out of destruction, out of ourselves.

“Open thy mouth wide, and I will fill it.” This is biblical imagery at its finest — just the grubbiest, most carnal expression of the most basic human experience imaginable. Yet it contains the absolute height of philosophy. It’s the same as Communion, the Eucharist. That mysterious bodily union is being typologized here. But it’s also pointing to the mouth of our soul, the mind, the nous. Open your nous wide by means of self-emptying love for God and neighbor, and Yahweh will fill you with all His divinity — like a mother feeding her infant, or like a grandson feeding a bedridden grandparent. It’s enough to make a hesychast weep for days. I should want to use this line as the title of the book I’m working on. Yet a public perverted by sin hears it out of context and is moved to think of sexual innuendo. The thing is, that pattern’s not off; its mode is just wrong. This verse resonates with all aspects of human life, including the sexual — if, that is, in chaste dispassion we perceive what the true spiritual meaning and purpose of sex is. There’s nothing a celibate can’t participate in when we are dispassionately embraced by the Lord our Bridegroom, filled with His energy, and made to be the Body of Christ. This is the meaning of which sex should be the expression, even if the spirit of sin within us wishes to switch those positions.

ο. (vv. 11–13)

The Lord longs for His people. So, as in the beta-triad above, he sets an ordinance for Israel by bringing them out of Egypt and ending their hardship. But in liberating them, He does not enslave them again. They are free to go their own way separate from the Lord should they want, according to their own hearts. In the era of history ruled by the Church (thinking analogously), yes, there are many saints, many success stories. But there is also much apostasy, much refusal of God’s love — consequent to the fact that God’s love liberates and does not enslave — and that is what this omicron-passage focuses on.

The eta-couplet, however, wistfully imagines the opposite of apostasy. Yes, the Greek here builds a grammatical connection between this verse and the following (vv. 13–14), as reflected in this English translation, but in the Hebrew this verse is a more independent burst of longing, as the King James has it, “Oh that my people had hearkened unto me, and Israel had walked in my ways!” This burst of love for enemies, spreading out to all God’s people, ultimately is what this omicron-triad is about, and it also identifies the behavior of the Church viewed positively, even in the midst of the world’s spurning. For the Body of Christ is Christ and behaves as He behaves.

ω. (vv. 14–16)

The Lord’s love for His enemies, as well as the Church’s love for His enemies, which is the same, hits said enemies with a strong, humbling force. It discomfits them. In the end — as at harvest time, as on the Day of Atonement — that which should be nourishment and satisfaction functions instead as judgment, as a revelation of all they lack, as a revelation of all the lies they’ve told. Their time shall come, in that age. The devastating insinuation here is that the Lord’s people, those whom He rescued from slavery and joined to Himself in covenant, may yet abuse their freedom and become His enemies. Christians should understand this applies to them even more so than to the Judeans of old. Indeed the covenant made with Christians is more consequential.

But the psalm’s final verse, recognizing which verse serves as the psalm’s pinnacle, returns to the image of feeding. The honey out of the rock reflects the sweet waters of Meribah referenced at the center’s base. And the fat of the wheat pairs with the opening inscription’s mention of winepresses to comprise the Communion alluded to at the center’s pinnacle: “Open thy mouth wide, and I will fill it.” Fill it with wheat and wine and honey/water? So the words of the psalm suggest in the psalm’s extremities. But simultaneously, at the pinnacle, where our mouth is opened wide, the Lord doesn’t say He will fill it with something else. He says He will fill it.

With mouths agape, then, let us rejoice in God our helper. Let us shout with joy to the God of Jacob. Sing it loud:

Works Cited

St. Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory of Nyssa’s Treatise on the Inscription of the Psalms, td. by Ronald E. Heine (Clarendon Press, 1995).

Donald Sheehan, The Shield of Psalmic Prayer (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2020).