Reuniting time and eternity via the Christian week as revealed in the Octoechos

Fitting the symbolism of a five-day work week and a triadic weekend into a seven-day cycle

Time in its corrupt form brings death and corruption. Time brings low the mightiest among us. As Homer describes it, the melody of time reduces Odysseus to the form of a woman weeping bright molten tears as she, discovering her husband dying on yesterday’s battlefield, reaches down to embrace him only to feel the tips of time’s spears prodding her from behind and carrying her off into an existence of loss and slavery and grief (Odyssey VIII.560ff). Time makes constant widows of us all. It divides us from what we know of our past, while the only thing we know for certain of our future is eventual death. Time is death.

But that’s its corrupted fallen form. That’s only how it behaves when it is divided from its meaning — widowed, you might say. In its original wedded mode, in accordance with its logos, time is merely the ordered expression of its partner in marriage, eternity. Time does not divide when time is not divided from eternity. Eternity holds things together. But an eternal synaxis of all created things appears on the plane of the material world as chaotic, as “without form” (Gen. 1:2), and so the pre-eternal God makes time to proceed along its axis so as to bring form to the symbolic expression of the eternity of creation.

If you want to know the incorrupt nature of time — its order, and how it relates with eternity like a body and soul without separation or confusion — you are invited to immerse yourself in the liturgical cycles of the Orthodox Church. Through the order of prayer, both in fasting and in feasting, one brings one’s body and soul into symbolic unity alongside earth and heaven, and time and eternity, according to the patterns of creation as originally intended.

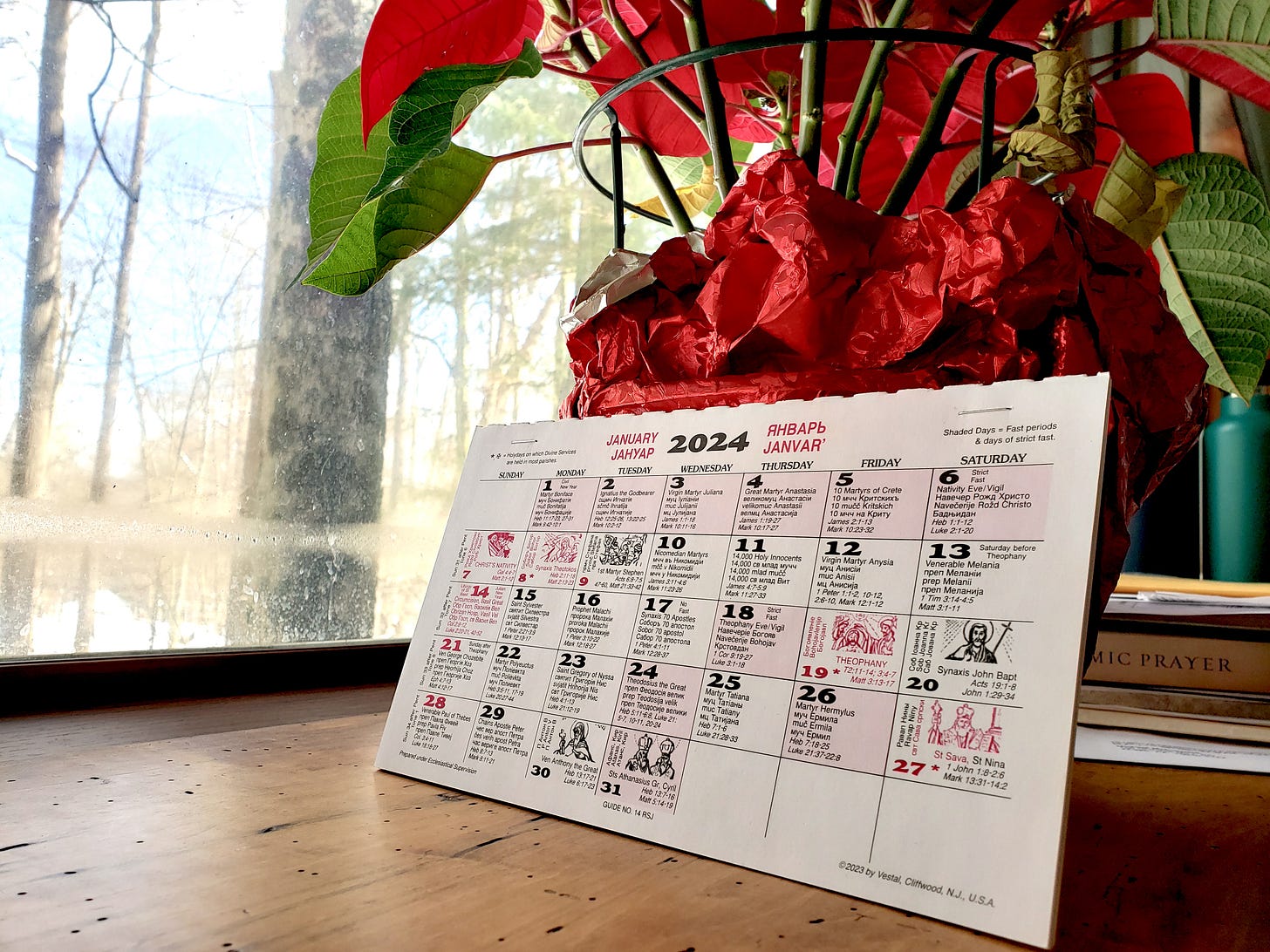

In Orthodox liturgical practice, for each cycle of time, there’s a book of prayers that traces its circuit. The day is measured with hours, and so the daily cycle is represented by the Horologion, or “Book of Hours”. Eight services, symbolically attributed to eight different times at three-hour intervals, plot out the pattern of each day. There are four longer services: Vespers (6 pm), Compline (9 pm), Midnight Office (midnight), and Matins (3 am); and then four shorter services all in the same form: First Hour (6 am), Third Hour (9 am), Sixth Hour (noon), and Ninth Hour (3 pm). In monasteries where this cycle is maintained, the services are usually observed not at their symbolic times but in three different aggregates: Vespers is, at the close of daylight, the first service of the cycle, but to it is adjoined beforehand the last service of the previous day, Ninth Hour. Later in the evening Compline is served. And in the very early morning, Midnight Office, Matins, and First Hour are served in aggregate, and to them can be joined Third and Sixth Hours. (Practice of course varies.) Within the framework of these daily services of the Horologion, additional material is observed from other liturgical books representing the other temporal cycles.

While the day is measured in hours, the year is measured in months, and so the Menaion (based on the root word for month) is a twelve-volume set of services for each date in the calendar — usually for a “saint of the day” but also for feasts of the Lord and the Mother of God like Nativity, Theophany, and Dormition. All these multitudinous celebrations serve like the stars and planets in the firmament to orient us in time and space on a wide scale.

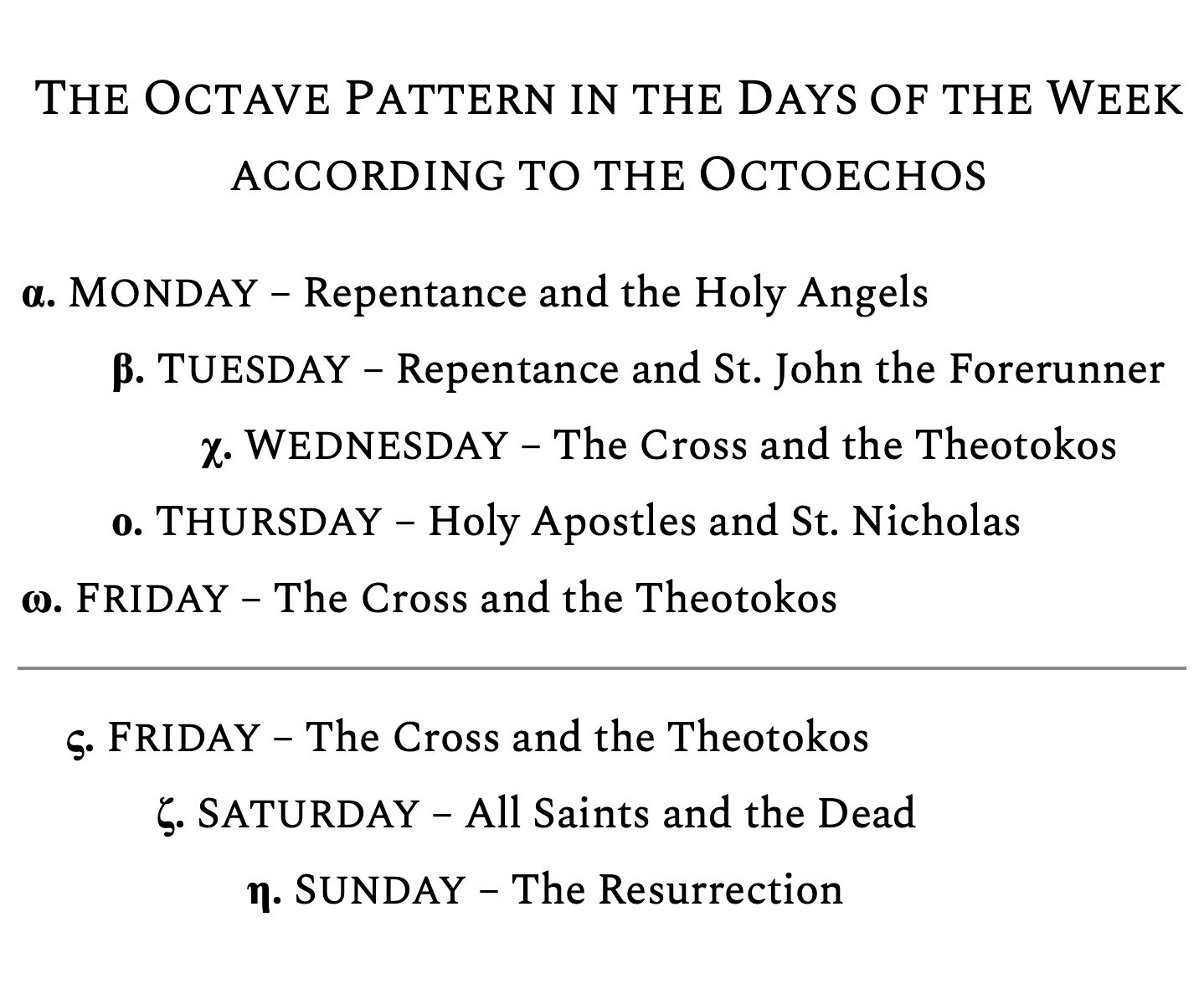

And to the daily and yearly cycles is added the cycle of the week. These portions of the services are provided by the Octoechos, a word which means “eight tones”. There are eight sets of musical tones, and each one takes a turn fulfilling the prayers that mark out the pattern of the week. The text of the prayers, which are mainly attributed to St. John Damascene in the eighth century, differs for each tone, but the form remains the same. Each day of the week has a theme, a commemoration, a protector. The ancient pagan way of naming the days, retained in the English language, was after the planetary gods believed to be each day’s principality. Zeus/Jupiter, for example, was perceived to be the god of Thursday, or “Thor’s day” in Germanic languages such as Old English. The ancient Christians perceived a different pattern of daily principalities and protectors, reflective of their own revealed cosmology. The formal prayers in the Octoechos trace this eightfold pattern that accounts for the marriage of both sevenfold time and an eighth-day eternity, the specifics of which I’ll get to in a bit.

Firstly, though, it is necessary to explain the complexity that results when a temporal span of seven days is used to symbolize an eightfold pattern of time and eternity. Sunday is the first day of the week, but it is also the eighth day, the first day of a new creation. As Christian practice was freed from bondage and allowed to flourish socially and economically, Sunday’s identity as the eighth day came to take precedence over its identity as the first day of the sabbath week. Once Christians were in power, people would rest on Sunday and not go back to work until Monday.

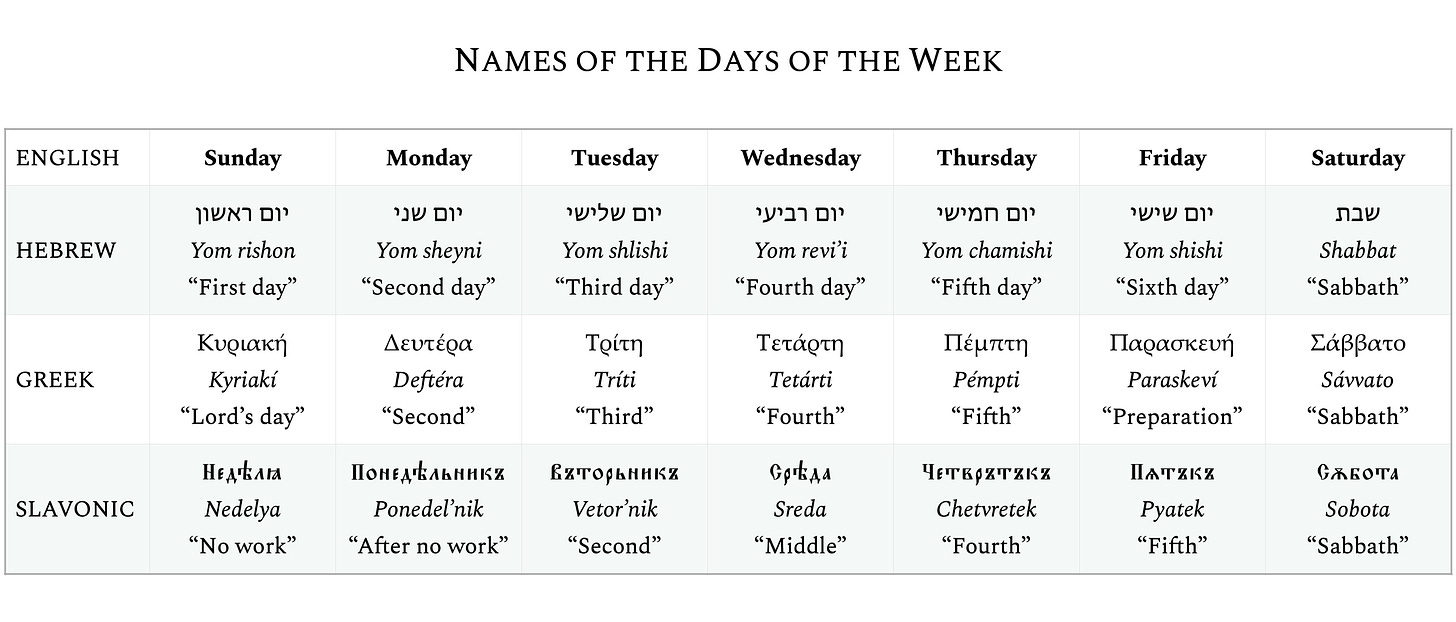

You can see this transformation in the Greek names given by the Church to the days of the week. At first, in the very early Church, the new Greek names assigned to replace the old pagan ones were based, naturally, in Judean practice. But by the time the Triumph of Orthodoxy happened in the ninth century, upon which occasion it could at last be said that Hellenic culture had been fully converted to the Church, Greek missionaries armed with texts like the Octoechos would pass on a different sensibility to their Slavic neighbors to the north.

Friday, the original “Sixth day”, was called in Greek “preparation” because it was the preparation of the Sabbath, even as Christ’s Crucifixion occurred in preparation of the Great Sabbath, when He rested in the tomb. Saturday is consistently understood as the Sabbath and named as such. Sunday, meanwhile, merely the “First day” in Hebrew, in Greek becomes known as the “Lord’s day” in honor of the Resurrection and the dawn of eternal life (cf. Rev. 1:10) — a different kind of “first day”, one with no evening, but which contains within it all the other days. This is the eternity that interpenetrates all time and holds it together. This threefold pattern of the weekend is what I’m indicating when I use my ς–ζ–η (stigma–zeta–eta) symbols, the Greek numerals for 6–7–8.

When Sunday comes to mean more eighth day than first day, however, the identity of the fivefold work week around which the weekend sabbatical is built shifts. You see this in Slavonic vocabulary. While the sabbath identity is retained for Saturday, Nedelya (Sunday) translates literally as “no work”, and, like the Hebrew word shabbat, besides specifying the day that serves as the head of the week, Nedelya also just means “week”. Ponedel’nik subsequently refers to the day “next to” or “after” Nedelya — after Sunday, that is, or most literally, “after no work”, as in “Enough rest, get back to work.” (After celebrating Sunday properly as a Christian, I’m always so ready and eager to get back to work on Monday.) Monday then, literally called “Second” in Greek, becomes in practice the first day of the work week. This discrepancy between name and practice (surviving today in Modern Greek) was very well established by the time Greeks began creating a Christian Slavic terminology for first Moravian and then Bulgarian converts in the ninth century. As you can see from the Slavonic names for Tuesday through Friday, the numbering of the days of the work week have shifted one over from the Greek. This idea of Monday through Friday as a fivefold structure with Wednesday as a “middle” is exactly the sense you get from daily worship according to the Octoechos.

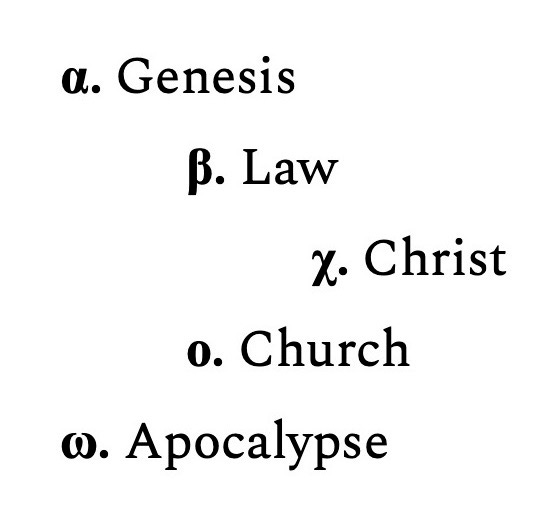

Let’s examine, then, that weekly pattern of prayer. To do so, let’s first review the thumbnail understanding of the cosmic chiasmus as I’ve explained it elsewhere:

This fivefold sequence labels the fractal shape of history objectively understood. The observation of Monday through Friday in the Octoechos, I believe, hews closely to this pattern. In fact, I think following the weekly worship of the Church was a decisive influence on my seeing this pattern elsewhere.

When you get back to work on Monday, repentance comprises an essential component to one’s assimilation to the incorrupt model of time, undivided from eternity, and this necessity carries over into Tuesday and remains implicit throughout the week. Thus the services for Monday and Tuesday feature first of all sets of verses focusing on repentance. When it comes to the troparion and kontakion (the “hymns of the day”) for these first two days, however, it’s the subject of the second set of verses, to either the Holy Angels or St. John the Forerunner, that forms the focus of attention.

Indeed, with angels (α.) serving as the principalities of creation, they rightly are recognized as the patrons of the first day of the work week. Then St. John the Prophet, Forerunner, and Baptist of the Lord (β.) recapitulates all of revelation under the Law and the Prophets before Christ. The Cross (χ.) is said in catechisms to be commemorated on Wednesdays because this day marks the beginning of Judas’s betrayal during Holy Week. That aspect isn’t at all highlighted in the Octoechos prayers, however. The most apparent reason the Cross marks the day known in Slavic languages as “Middle” is because the Cross is placed in the center of creation, according to biblical geography and according to the cosmic chiasmus as observed in other places. (It’s the same reason the Third Sunday of Lent is the Sunday of the Cross, but I’ll have to get to the Lenten Triodion in a separate post.) The Holy Apostles (o.), moreover, rule over the fourth day of the work week as leaders of the Church established by the Spirit’s descent after Christ’s Ascension; St. Nicholas, fourth-century bishop of Myra, joins them as the exemplar of apostolic succession. The Cross and the Theotokos (ω.), with prayers to the latter being particularly focused on the Mother of God’s relationship with the Cross (“stavrotheotokia” the prayers are called, stavros meaning cross), return for the fifth day of the work week, serving as the revelation of the meaning of all things, and their telos.

In their honoring the Cross, furthermore, both Wednesdays and Fridays are fast days, a practice of the Church dating to the first century as documented in the Didache, an early work of apostolic literature written in Greek likely after the destruction of the Second Temple. Among the Judeans of the time, it had been customary to fast on Mondays and Thursdays, which the Didache rejects: “But do not let your fasts coincide with those of the hypocrites. They fast on the second and fifth of weeks [Mondays and Thursdays], but you must fast on the fourth and on the preparation [Wednesdays and Fridays]” (8:1). Nevertheless, monastics in the Church traditionally do fast on Mondays also, not for the ancient reasons rejected by the Church, but in solidarity with the bodiless spirits commemorated that day. As a result the three fasts on Mondays (for monastics), Wednesdays, and Fridays serve to imprint pragmatically and bodily in the lives of the faithful the fivefold chiastic structure of the work week — to which is added, of course, the transformative triadic pattern of the weekend. This compound symbolism requires we count Friday twice, however.

With Sunday losing its ambiguity, practically speaking, as not only an eighth day with no evening, but also the first day of a repeating cycle, the ambiguity necessary to fit eightfold symbolism into seven days shifts rather to Friday as both the fifth day and the sixth. I believe this ambiguity is intuitive to us even in our post-Christian secular lives, as Friday is both the last day of the work week and the first day of the weekend. In the Octoechos, Friday’s commemoration of the Crucifixion (ς.) leads into prayers to all saints and remembrance of the dead (ζ.) on the Sabbath, culminating in celebration of the Resurrection (η.) on the Lord’s day. In modern Russian, the word for Sunday even is “Resurrection”, or Воскресенье (Voskresen’ye), though other Slavic languages retain forms of the earlier Slavonic Nedelya. All told, I think that while the Slavic numbering of Monday through Friday, centered on Wednesday, better expresses the fivefold chiastic base of the work week, the Greek words for the days of the week better express the 6–7–8, with Friday being called “Preparation” instead of “Fifth”.

And Sunday, whether in Greek or not, is the Lord’s day (again, cf. Rev. 1:10). The Lord, however, is Christ, both God and man, containing all things. He is the pre-eternal God made fully human, with deified mind and body both situated in and encompassing all spiritual eternity and material time. In the Octoechos, the canons provided for Matins on this day include not only one commemorating the Resurrection of Christ, conceived both historically and symbolically, but also — if the rank of the adjoining Menaion service allows — one commemorating both the Cross and the Resurrection together, as well as one to the Theotokos. Remembering the Cross on Sunday is a powerful way of keeping in mind that the Resurrection is of the flesh, and that the cross-shaped cosmic chiasmus of the work week culminating on Friday is symbolically included in, not separate from, Sunday’s worship. The presence of her who is known as the “Panaghia”, the “All-holy” Theotokos, likewise underlines the inclusion of all creation in Sunday’s divine embrace. When one or both of these secondary canons is eclipsed by a higher-ranking feast in the Menaion, the cosmic symbolism remains the same, just with some added specificity.

Eternity contains all of time. And time experienced in communion with eternity — because experienced in communion with God the Word both pre-eternal and incarnate — has no death within it. Incorrupt time is merely the pleasing order of eternity, pleasing in the sense that each day that God creates in the beginning of Genesis He sees as good, and the seventh day He blesses. When He blesses the fish and birds on the fifth day and the human being on the sixth day, it is so that they might be fruitful and multiply. Thus when he blesses the sabbath on the seventh day, it is so that the weekly cycle representing all time might abound unto eternity. Time, which is not eternal, is blessed to commune with the eternal. In Christ, our Creator and Redeemer, each day, each hour, each month, each year, each week rises like incense to be a sweet savor to the Lord. In the Resurrection, death is no more.