Teeeth!

Something to ruminate (with)

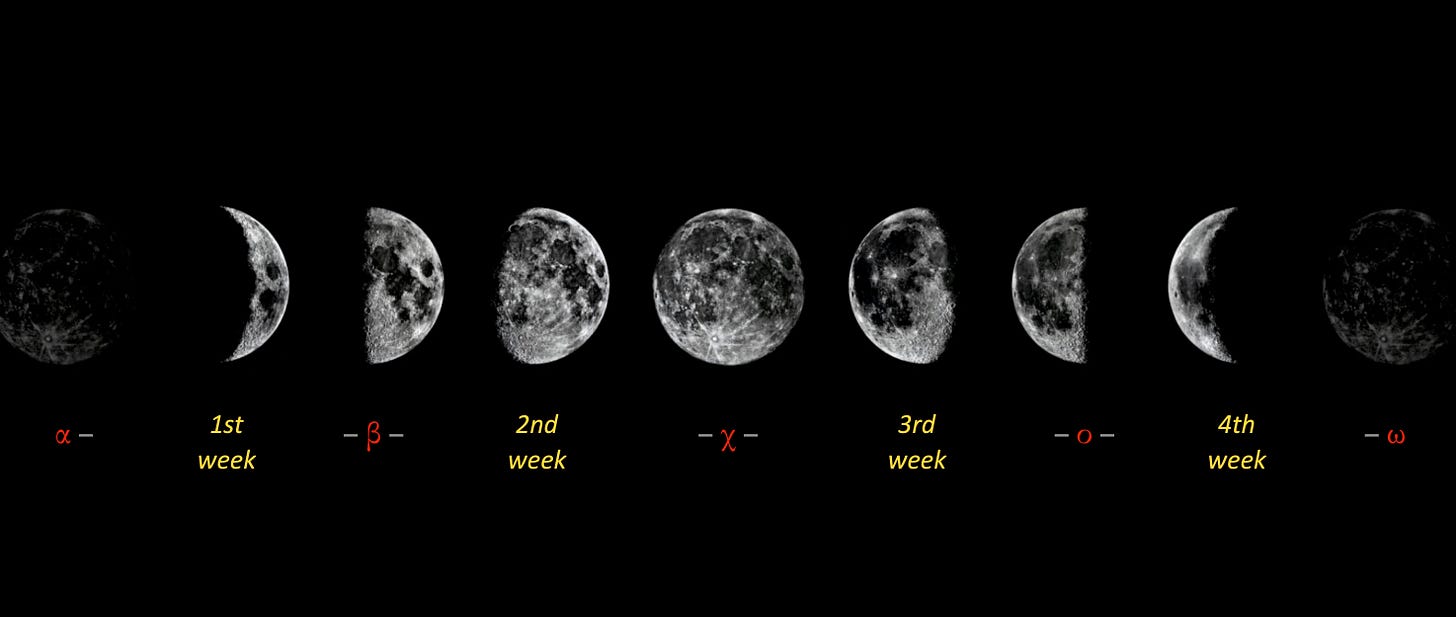

Without looking, do you know how many teeth we have? I didn’t until one day a few years ago I wondered about it and looked it up. It was a fortuitous time to do so because I had recently discovered something wondrous about the formal structure of the four books of Kingdoms. Each of the books, variously called 1–4 Kingdoms or 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings, is an octave shape. I didn’t force this structural interpretation. I had gone through each book willing to see any shape or no shape at all, but each one, one by one, made the most sense as an octave. You can see the outlines on my website. As I was uploading them there, I made the realization that four octaves symbolize four weeks, which shape matches a lunar month. I realized the narrative of the four books of Kingdoms indeed follows the structure of a lunar month, with the erection of the temple symbolizing the full moon. The lunar month begins with a new moon — like having no temple, and no king to build the temple. A light appears in the form of David, but the darkness of Saul predominates. In the span of two weeks, 1–2 Samuel, the light of David waxes strong over the darkness until the moon is full and he becomes king. Then at the beginning of 1 Kings, when the moon is still full, his son Solomon builds the temple. Immediately darkness creeps in, however, as the kingdom is divided in the next generation. Across the next two weeks/books, darkness and light do battle again, this time in the form of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms. As the moon wanes, darkness prevails. By the end of 2 Kings, the temple is destroyed and the seed of David is stripped of power, the lunar cycle reverting to a new moon state.

Then I discovered, not long thence — with a spark of joy that has not faded — human teeth are organized according to the same four-week pattern!

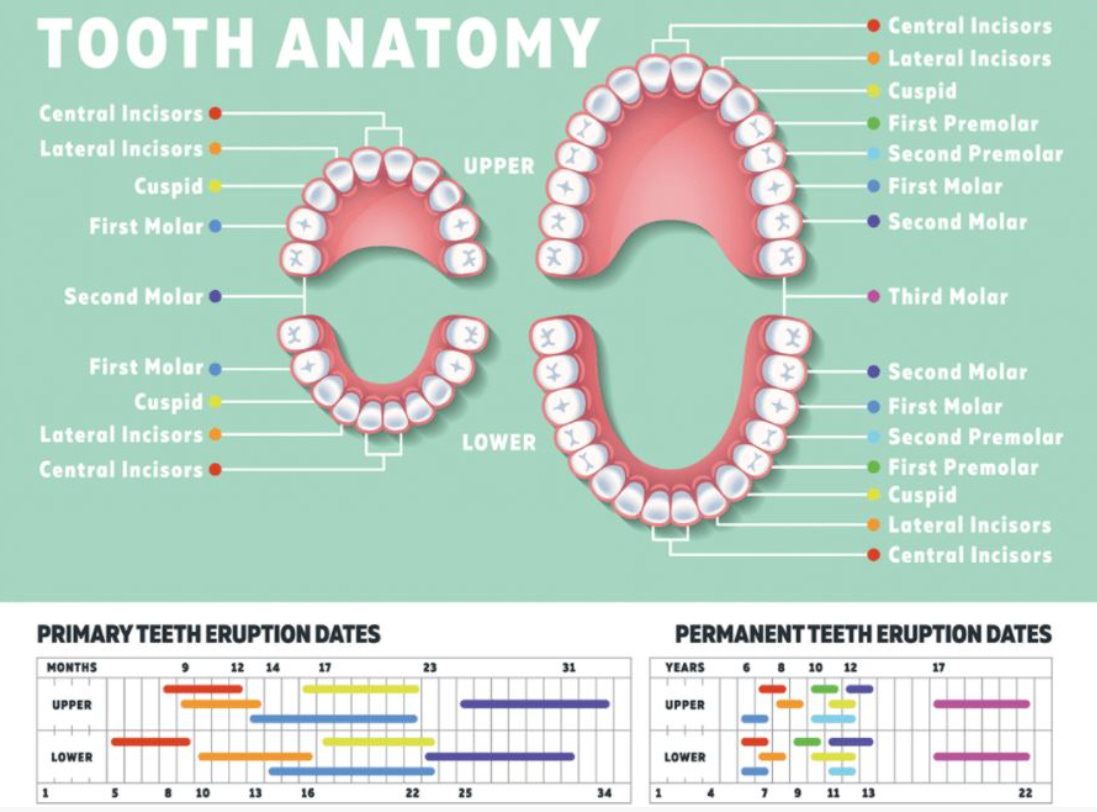

A lunar month rounds to 29 days. That’s four seven-day weeks plus an “eighth day”. The eighth day is symbolic of eternity, which permeates the whole seven-day cycle of time. Like the Eucharist, it is distributed but not disunited — each Sunday is the “eighth day”. Mathematically, (7 × 4) + 1 ≠ (7 + 1) × 4; twenty-nine does not equal thirty-two. But symbolically they do equal each other because the eighth day crowns both the whole and the parts. Hence, if we understand the eighth day correctly, the four Books of Kingdoms can symbolize the 29-day lunar cycle (7 × 4 + 1) in their 32 parts (4 × 8). Excitingly, adult human teeth do the same.

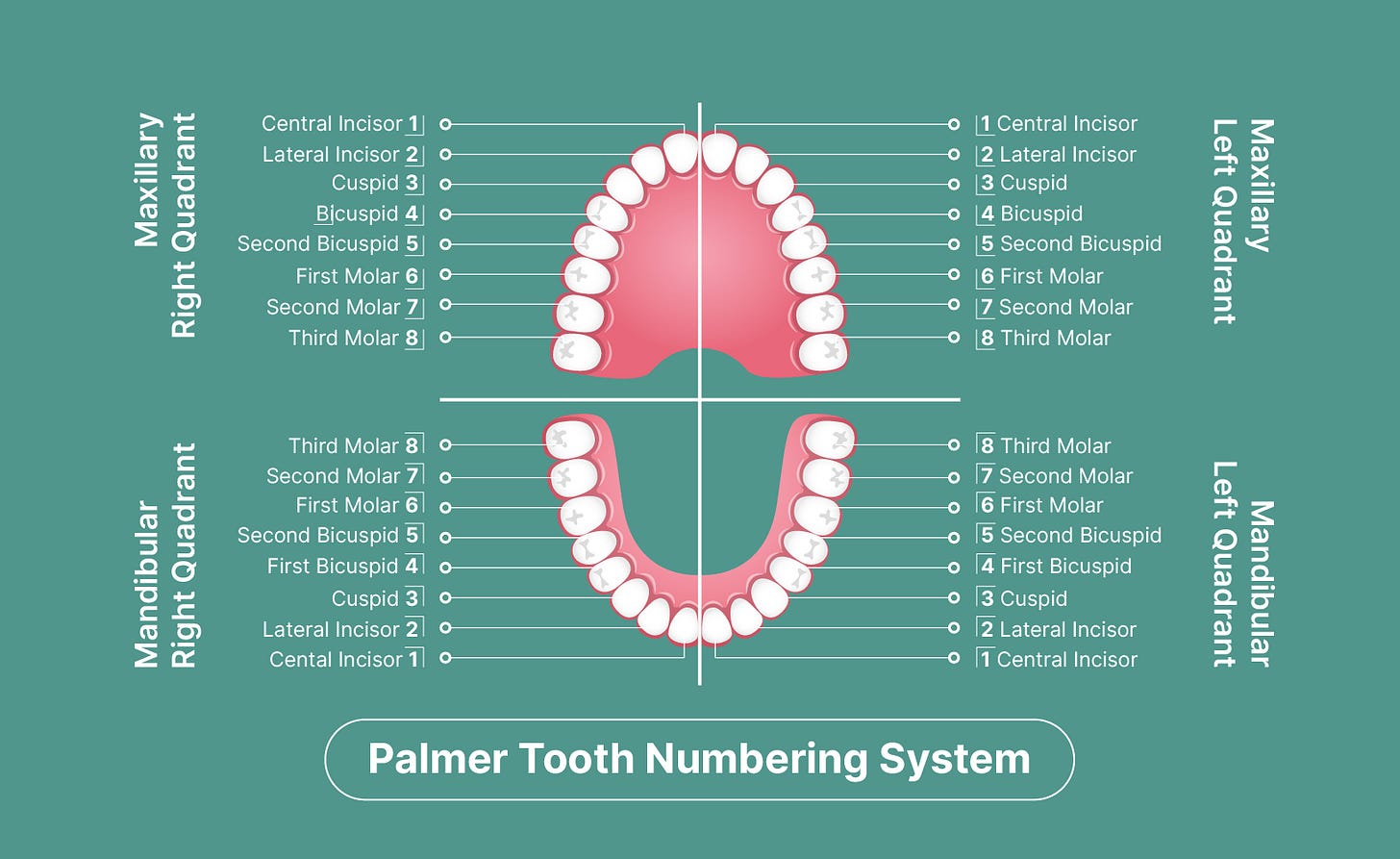

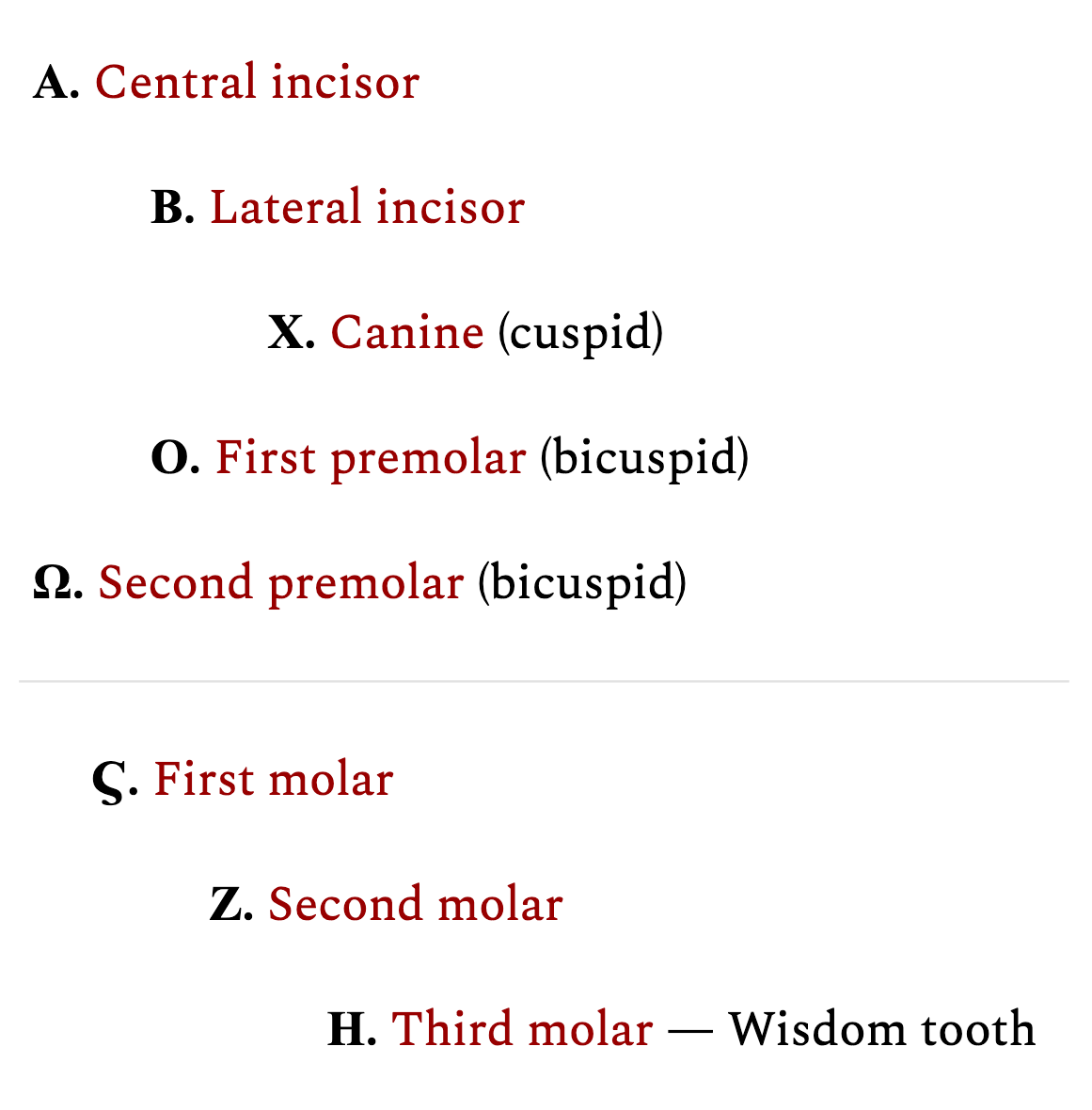

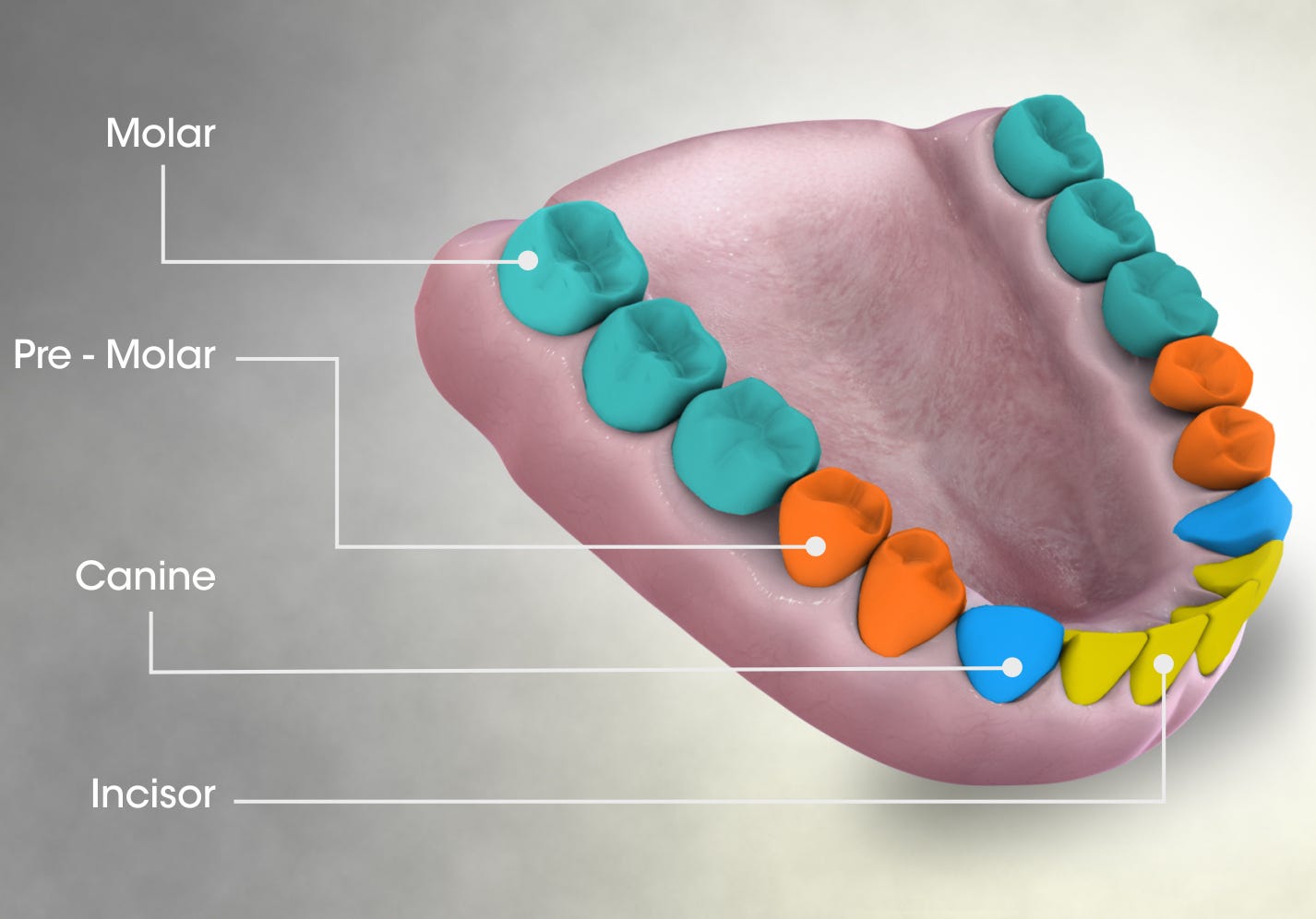

They split into four sets of eight. It’s even easy to see, according to this pattern, how from ancient times there is ambiguity naming and numbering the four Books of Kingdoms. Calling them 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings, according to the Jerusalem tradition (it’s not a Masoretic innovation), is like thinking of the teeth as right and left maxillary (upper jaw) and right and left mandibular (lower jaw). Or like the Septuagint tradition, you could think of them as four quadrants of one unit. It’s the same with the lunar cycle. It’s either a four-week unit, or there’s a two-week waxing period paired with a two-week waning period. This is why the seven-day week is a natural unit, by the way, and not just an invention of the Torah; ancient Babylon observed it first. But sevenfold time calls for an eighth-day eternity, and we’re back to the octave structure. Now it’s time to look at the sequence of a dental quadrant:

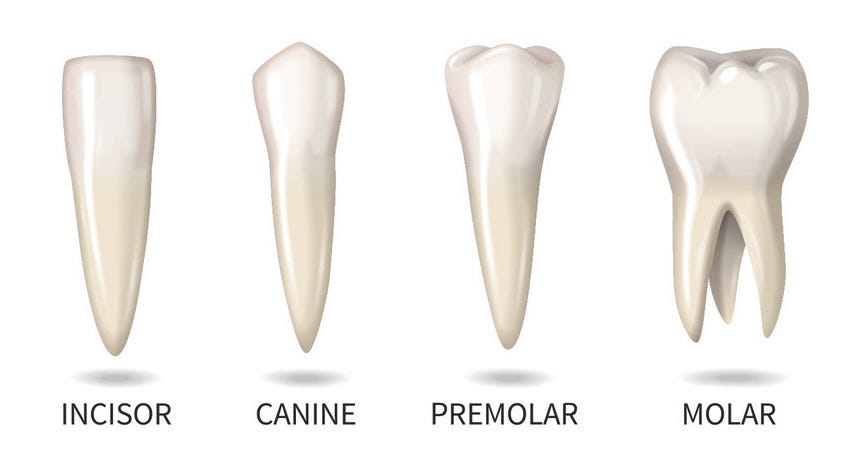

It’s even in an octave structure, a fivefold chiasmus plus an ascending triad! The first five teeth in the sequence pivot on the third in order, the piercing canine tooth (Χ.), which uniquely crests in one point, or cusp, and thus is also called the cuspid tooth. This is the corner hinge between the front teeth and the back teeth. The frontmost tooth, meanwhile, is the central incisor (Α.) so prominent in the upper jaw; the central incisor is where the sequence of each quadrant begins. Its crown is a flat edge designed for slicing and thereby beginning the chewing process. The lateral incisor (Β.) stands next to it, doubling its power with the same type of flat-edge crown.

Behind the canine tooth are set the premolars, also called bicuspids because they have an outer and inner cusp, with a fissure in between. They combine the piercing capability of the canines with the mashing capability of the molars. The first premolar (Ο.) looks like the canine on its face, its inner cusp not outwardly visible. On the upper jaw, this tooth frequently has two roots, but sometimes only one (the other premolars only have one). The second premolar (Ω.) sits behind it, completing the symmetry with the two incisors on the other side of the canine. In the lower jaw, the inner cusp of the second premolar rises to two different points, one bigger than the other.

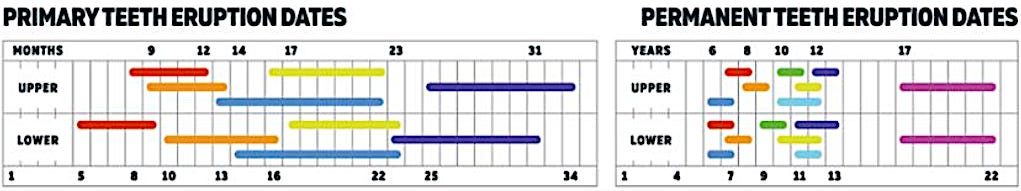

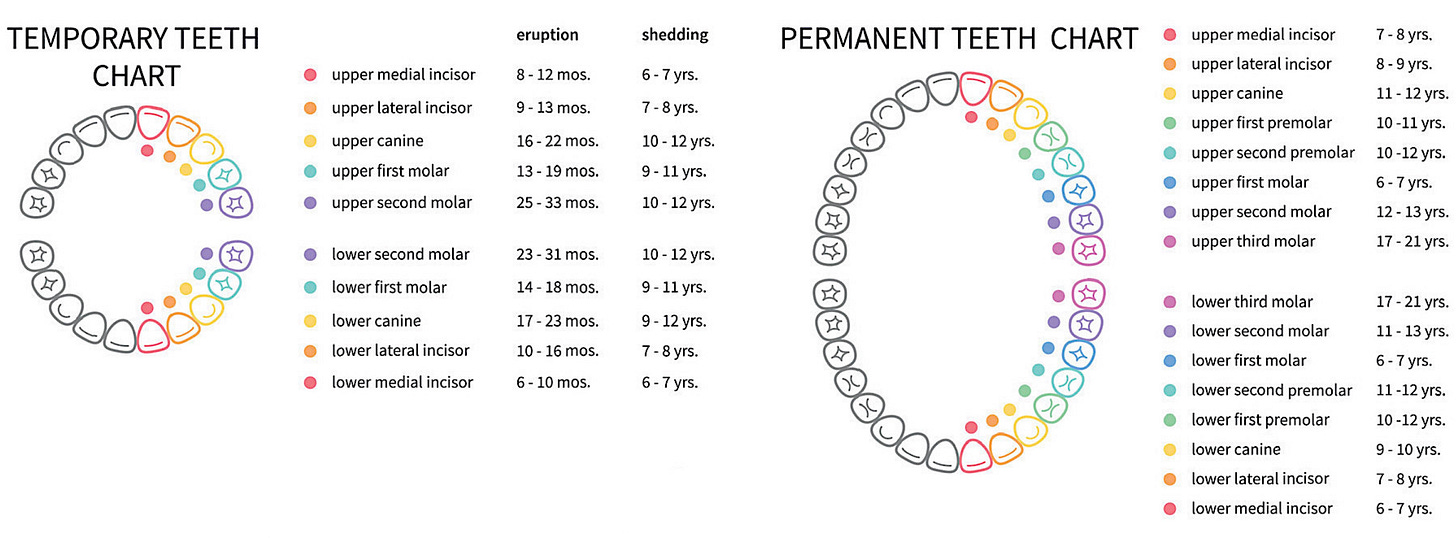

Then come the three molars, designed for grinding: the word molar comes from the Latin for millstone. They feature four or five cusps around a central fissure. They come in — “erupt” is the technical term — in three distinct stages, symbolic of the triad of purification, illumination, and perfection. The first molar (Ϛ.) erupts first, usually before any other permanent teeth, fitting in behind the baby teeth molars around age six or seven. The second molar (Ζ.) erupts generally at the end of the process of replacing the baby teeth, at around ages eleven to thirteen, at the outset of puberty. The third molar — also known as the wisdom tooth (Η.) — erupts years later than all the rest, in the late teens or early twenties, in time for the onset of adulthood, when one should be ready to get married or join a monastery. Wisdom teeth not uncommonly have trouble erupting, and modern dentistry likes to remove them beforehand just in case, even though usually they don’t present any problems even when they’re irregular. I trust my readers can read the symbolism in all that. I would not recommend parents have their children’s wisdom teeth removed unless it became strictly necessary.

But the issue of eruption and dental development raises the question: What about baby teeth?

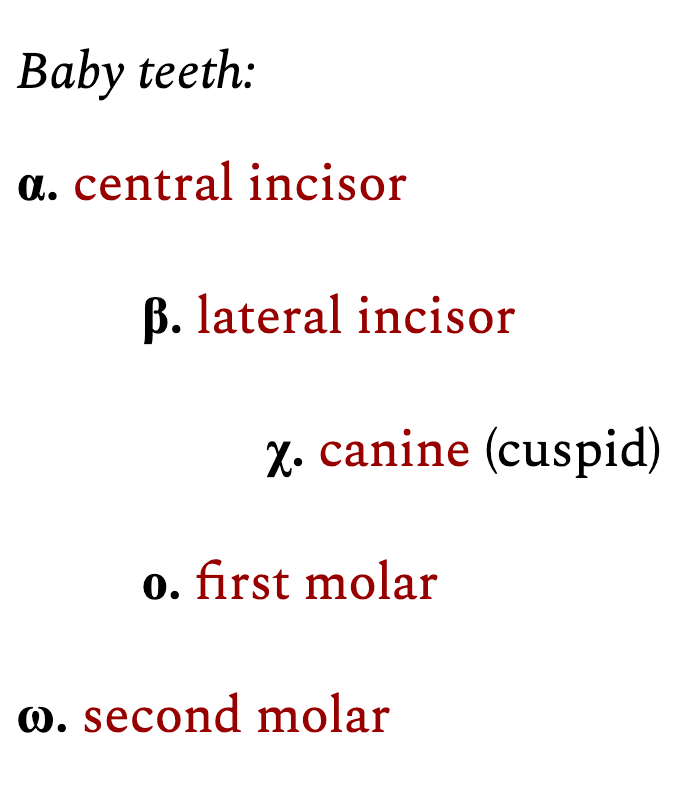

Before the thirty-two permanent adult teeth, come twenty temporary baby teeth, also called deciduous, like the trees that shed their leaves. These twenty teeth come in quadrants of five — a simple fivefold chiasmus. Two incisors and two molars hinge on a central canine. The first three are replaced with adult teeth of the same kind. The baby molars hold the places to be occupied by the adult premolars; the first adult molar grows in behind them.

I had this realization a few years ago when I was trying to figure out how to proceed to write about all the structural forms I had been contemplating for years. Seeing the shape of baby teeth relative to adult teeth gave me the confirmation I needed to write “The Cosmic Chiasmus”, understanding that people need to begin with the pentad and just work with that first. “The Cosmic Chiasmus” is just the deciduous baby teeth. Those following along as I try to write about the octave are now growing a permanent set of chompers.

This unexpected confluence of images — the lunar month, the Books of Kingdoms, and human teeth — ignites endless joy and wonder in me. It reminds me of Psalm 80, the chiastic center and numerological heart of the Book of Psalms, which says both, “Sound the trumpet at the new moon, at the notable day of our feast,” and “For I am the Lord thy God who led thee out of the land of Egypt; open thy mouth wide, and I will fill it” — yeah, fill it with teeth!

This is one of my favorite articles