What are heaven and Paradise? Is there a difference between them?

“In the beginning, God made the heaven and the earth” — God created the macrocosm of heaven and earth, and then, like a temple fractally recapitulating the universe within the universe, He made man, on earth, out of breath and dust — a microcosm of heaven and earth. He planted a garden in which to put the microcosm He had created. This garden is called Paradise, from a Persian word for walled garden. So heaven is of a nature other than earth, whereas Paradise is a place on earth set apart from the rest of the inhabited world (in Greek the oikoumene, or ecumenical world).

In the office of First Hour, there is a prayer to the Mother of God that asks rhetorically, “What shall we call thee, O thou who art full of grace? Heaven? For from thee hath dawned forth the Sun of Righteousness. Paradise? For from thee hath blossomed forth the flower of immortality.” You can see in this poetic comparison that heaven is from whence things emanate from above down to the earth, whereas Paradise is the place where things emerge up from the earth. But there’s more to Paradise that sets it apart from just anywhere on earth that emergent vegetation is found, something that makes its flower the flower of immortality, its tree the Tree of Life.

What sets Paradise apart from the ecumenical earth is that, like the human being it hosts, Paradise is the center of where heaven and earth meet. True, there is no place that heaven and earth don’t meet. Heaven covers the whole earth as a dome, and there is no place on earth not covered by heaven. I speak of the immaterial heaven and the entire material realm — but within the material realm, the material heaven (Hebrew and Greek don’t have a separate word for “sky”) and material earth form perfect symbols of the immaterial and material realms. The immaterial, noetic realm (heaven) penetrates and establishes the material realm (earth) perfectly, like meaning and expression. There’s no place they don’t meet, but... there is a center of their meeting; and that’s Paradise. As such, Paradise is not just a walled garden, but also a mountain.

A mountain is a place where heaven and earth meet. The creation of man brings breath and dust (heaven and earth) together in one being. Therefore, the garden prepared for him as a dwelling place is a mountain that brings heaven and earth together in one central place.

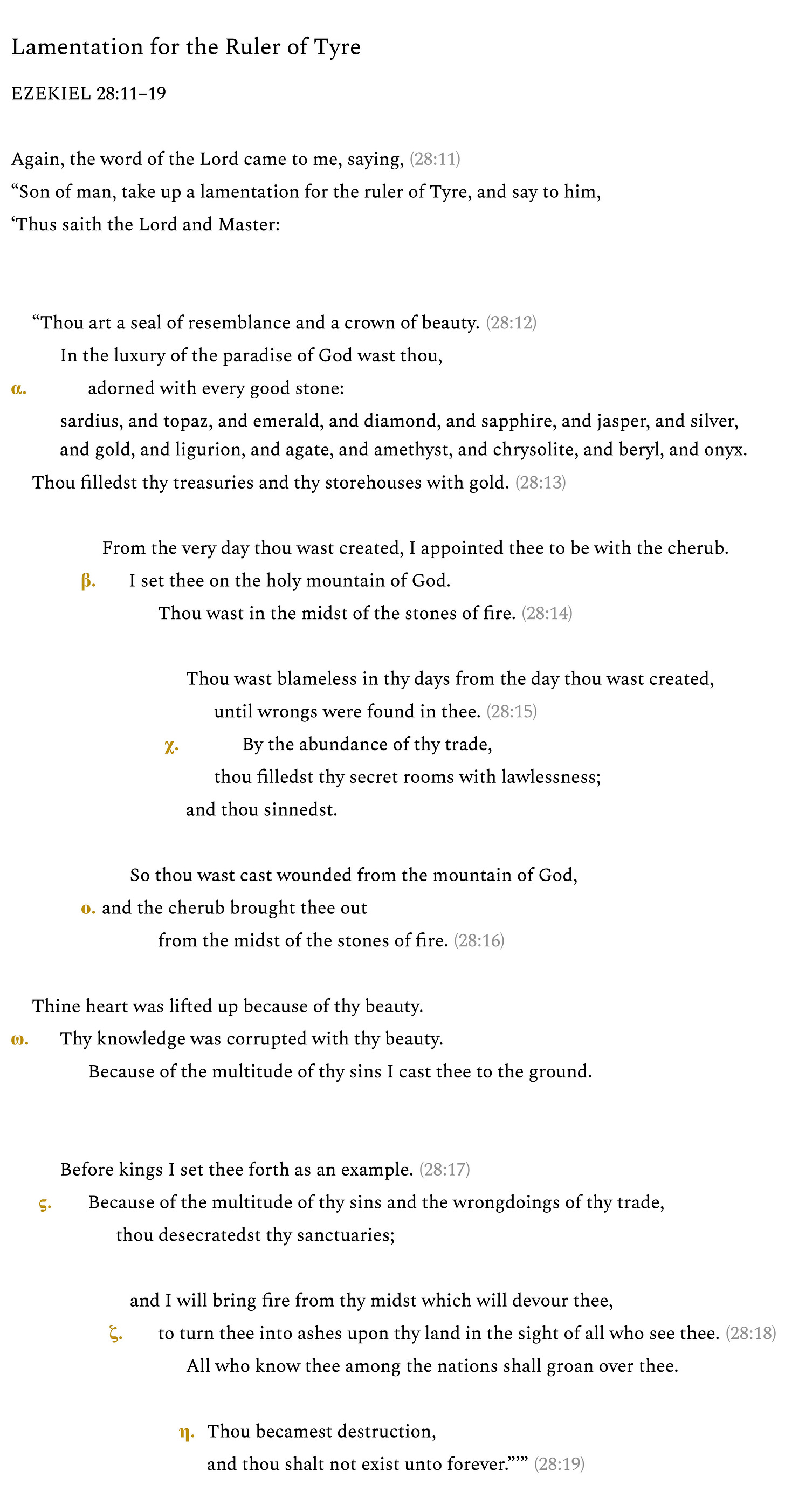

Of course, Moses doesn’t explicitly call Paradise a mountain in the Torah, but, as you may have heard, the Prophet Ezekiel does. Since this passage is cited much more often than it is read, I think it worthwhile to post the entire text here for review. It forms a nice octave shape. It is found in the Book of Ezekiel’s central section where he prophesies against the nations. He has already called out the city-state of Tyre and lamented it in chapters 26 and 27; at the beginning of chapter 28, he prophesies the ruler of Tyre’s personal overthrow, followed then by this lamentation:

The ruler of Tyre is likened to first-created man, ruling over creation as a “seal of resemblance” or likeness — that is, as made according to the image of God. The image of God is the Son, the perfect image of the Father. The Son becomes incarnate and unites created to Uncreated the way a mountain brings together earth and heaven. Man himself, such as the ruler of Tyre, is the seal of likeness resembling this Mediator, in his mediation of heaven and earth. The Paradise of God in which he dwells in Ezekiel 28:13 is called the mountain of God in verses 14 and 16. This is where heaven and earth are mediated. That is, Paradise is the center of their mediation.

How Paradise mediates earth is clear in that it is planted on earth and emerges from earth. How it mediates heaven is made clear in how the ruler of Tyre is cast down from it. He sins. As Adam before, whose story is in fact being reenacted, the ruler of Tyre fails to live according to the meaning of things and so is cast out of Paradise. Paradise, therefore, conforms to the moral dimensions of heaven. Sin is not tolerated there. It can occur there, if only because free-will endowed creatures are placed there. But it is not tolerated and occasions expulsion. “I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven,” Christ tells the Apostles (Luke 10:18). The demonic spirits, deviating from their meaning, fall from heaven and are said to occupy the “air,” a kind of earthy, material expression of a spiritual place. As in heaven, so on earth. When Adam and Eve deviate from the meaning of things, they are cast out from Paradise, and a cherub with flaming sword guards the way to the Tree of Life therein, lest their sin become the meaning of their lives. The ecumenical world can accommodate sin (disconnection from meaning and purpose) for a season before the judgment puts everything back right, allowing humans opportunity for repentance and return.

What are the soul and the heart? Is there a difference between them?

A girl in my Sunday school class, who is just ten years old but who reads at a high school level, asked me what heaven and paradise are, whether there is a difference between them. A few months later she asked me what the soul and the heart are, whether there’s a difference between them. She had no idea she was asking the same question. Symbolically, the pattern is identical between the two.

The heart is to the body what Paradise is to the earth. The heart is part of the body, the way paradise is a garden planted on earth. But the heart is a mountain where soul and body meet. The soul — the breath that animates the body — is present throughout the whole body, just as heavenly meaning is present throughout the whole earth. But Paradise is the center of heaven’s presence on earth, and so the heart is the center of the mind’s presence in the body.

For both soul and body have a chief element: for the body it is the heart, and for the soul, it is the mind (in Greek, the nous). There’s actually a song, from 1991, that expresses this quite simply and beautifully via the negative power of grief: “Unfinished Sympathy” by Massive Attack. In it, the guest vocalist Shara Nelson laments, “Like a soul without a mind, / in a body without a heart, / I’m missing every part.” It’s not necessary to name every part if you name the chief element of our two natures, breath and dust. If the mind and the heart are missing, then everything else is also.

For the heart is the center of the body, and the mind is the pinnacle of the soul. The chief element of the soul is described in vertical terms (I say here “pinnacle”) due to the immaterial nature of the soul, whereas the chief element of the body is described in horizontal terms (I say here “center”) due to the material nature of the body. Yes, the word heart can at times be used metaphorically for the center of something, as when Jesus says, “So shall the Son of man be in the heart of the earth for three days and three nights” (Matt. 12:40). But generally speaking, in Scripture and the Fathers, the word heart refers to the organ at the center of your body. It’s not a metaphor. The holy authors are referring to the center of your being, and the animated dust of your material body is who you are. Its center is the heart.

But there can be a meaningful difference in how the word heart is used in either a Scriptural or a patristic context. This is because there is a meaningful difference between Israelite and Gentile contexts. In Hebrew, there is no separate word for mind. In Greek, it’s nous; in Slavic languages, it’s ūm; in Latin, it’s intellectus. But in Hebrew literature, well, in places where you might expect a word for mind, the word heart, lev, is used instead. The heart, in Hebrew, is where understanding is had, where decisions are made, where things remembered are kept. The hesychastic literature of the Church describes the mind descending into the heart, but in biblical Hebrew, that appears to be its default position.

For example, Deuteronomy 6:5 says, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength,” which then becomes a prominent line in daily Hebrew prayers. But when it comes to translating this expression into Greek, the foremost of Gentile languages, in order to unpack the Hebrew word lev, either a new formulation of three has to be used, as at Matthew 22:37, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind (dianoia),” or, as at Mark 12:30, a fourth element has to be introduced: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind (dianoia), and with all thy strength.” The Gentiles, it can be concluded, are to learn from the Hebrews the more paradisaical purpose of their hearts.

God plants Paradise and walls it off after He makes man; then He brings Him into it. Similarly, starting from the dust of Sarai’s barren womb, the Lord forms Israel after the seventy nations are formed in a mode of punishment after Babel. All the nations had fallen from godly worship into a state of exile betokening death. Death is the separation of soul and body. For the Nations (the Gentiles), mind and heart are separated. The meaning and expression of heaven and earth are divided within them, and they are exiled from the mountain of Paradise. Israel, however, is made by God from scratch to be a Paradise among the ecumenical nations. In the Paradise of Israel, mind and heart unite as one, like on a mountain. Then after Christ’s Death and Resurrection, when the Judean synagogue is cast out, the nations who hitherto lived in death are invited to return to Paradise by way of the sign of the Cross, into which collapse, symbolically, both the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge from Paradise, as well as the guardian cherub’s flaming sword.

What must happen psychologically, however, for a Gentile to be grafted into Israel, is for the mind to descend into the heart (as the hesychasts have it), for heaven and earth to meet as one. The heart is a mountain. It is planted in the body so that from it may blossom the flower of immortality. This emergence occurs with the emanation of sun and rain from the heavenly mind, which descends on the mountain of the heart so that they touch. Paradise is the center of heaven’s presence on earth, and the heart is the center of the soul’s presence in the body, and as such they both are made the center of God’s presence on earth and in the body. God enters His creation. The Lord mediates soul and body, Paradise and ecumene, Judean and Gentile, heaven and earth, noetic and material, created and Uncreated.

Created human nature was made as the mountain where the divine Logos and creation meet. Christ is the center. He is the mediator of all things. Human nature is made according to the image of God so that the Image of God may unite human nature hypostatically to Himself. In order to participate, in order for the Holy Spirit to perfect the Incarnation in us and join us to the Body of Christ, we must prepare a place within us for the Holy Spirit. This hospitality requires the oneness of our soul and body, our heaven and earth, our mind and heart. By the power of the same Holy Spirit, we must be purified of our sin and have our life illumined by our purpose and meaning. This is what it means for a branch from the Gentiles to be grafted onto the tree of Israel; and this is what it means for the Godman to rise from the dead, to raise all of Adam from death to life. And since the Judeans’ exile, it would probably behoove them also to learn from the hesychastic example, in order to be grafted back, to be ushered back into Paradise, to be rejoined to Israel, the beating heart of the Nations.

“The fiery sword no longer guardeth the gate of Eden, / for in a strange and glorious way / the wood of the Cross hath quenched its flames. / The sting of death and the victory of hell are now destroyed, / for Thou art come, My Savior, crying unto those in hell: // ‘Return again to Paradise.’”

– kontakion of the Sunday of the Cross, repeated on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday in the central Fourth Week of Lent

Loved this! You articulated something I've been thinking about for some time. My meditations, however, have to do with the association between the masculine with the mind-above and the feminine with the heart-center. Which makes me want to ask you if you think my intuition is correct:

It does not seem to me that being "above" is any better or more important than being "at the center". Is God more "high/above" than He is "central"?

I've been trying to find the precise words/analogies to resolve the modern (?) problem where the feminine is devalued in favor of the masculine, but I think this is the analogy to do it.

It wouldn't be irrelevant to also point out that those who insist on the superiority of the masculine tend to tyrannize their own heart.

I have a general questions related to chiasmic patterns. I understand the basic "pattern" of the chiasm to be something like:

A

-B

A'

Where a climax/pinnacle/mountain top have an impact on what comes after in a reflective manner.

It can be something like:

A

-B

--C

-B'

A'

Or:

A

-B

--C

A'

-B'

Etc.

Does the shape of the pattern have a qualitative impact on it, or is it (and I say this without negative connotion) more of an ornamentation? If I have one or the other, does it "mean" something else? Is it used in different manner/context? etc.

I don't know if it makes any sense. I can try to reformulate it otherwise.