The kingdom of antichrist is within you, part 2

John Vervaeke’s advice on AI amounts to a false theosis

Two weeks ago (see Part 1) my head was occupied with the John Vervaeke video that I embed here below. I aimed to write about it but coughed up a bunch of requisite preliminary ideas instead. Throat cleared, I now aim to address this topic more directly, but do so with great trepidation. This is a knotty one. And the greatest hazards I face pertain to my own ignorance, of things both above and below — my lack of wisdom and my lack of understanding. Yet the combination of what understanding I have gathered and what wisdom has graced me spark concern in me sufficient to provoke an attempt to write about it. I drop my ideas here in this journal as if perching them on the edge of obscurity. If any of them be worthy of consideration, may they ascend through a collective awareness. May the rest, being unworthy, fall off their perch into the abyss.

I suppose this essay could be read apart from Part 1. But if any reader should at all have a negative reaction to anything said here, I ask they please consider at least reading the previous part before settling on an opinion.

I.

Before I begin, I must say I’m not immediately concerned about the feasibility of artificial super-intelligence, the credibility of fanciful predictions, whether or not we can or will create autonomous, autopoietic entities, or when it is we will absolutely, unavoidably, without fail do this. In the video that I’ll be talking about, John Vervaeke begins by warning against belief in exponential growth of science and technology, but then later on assumes certain impressive advances will happen within a decade. No matter. What concerns me most is what our speculation and thoughts on these issues reveal about our immanent spiritual condition.

For lack of a better starting point, then, let me first look at the video’s thumbnail:

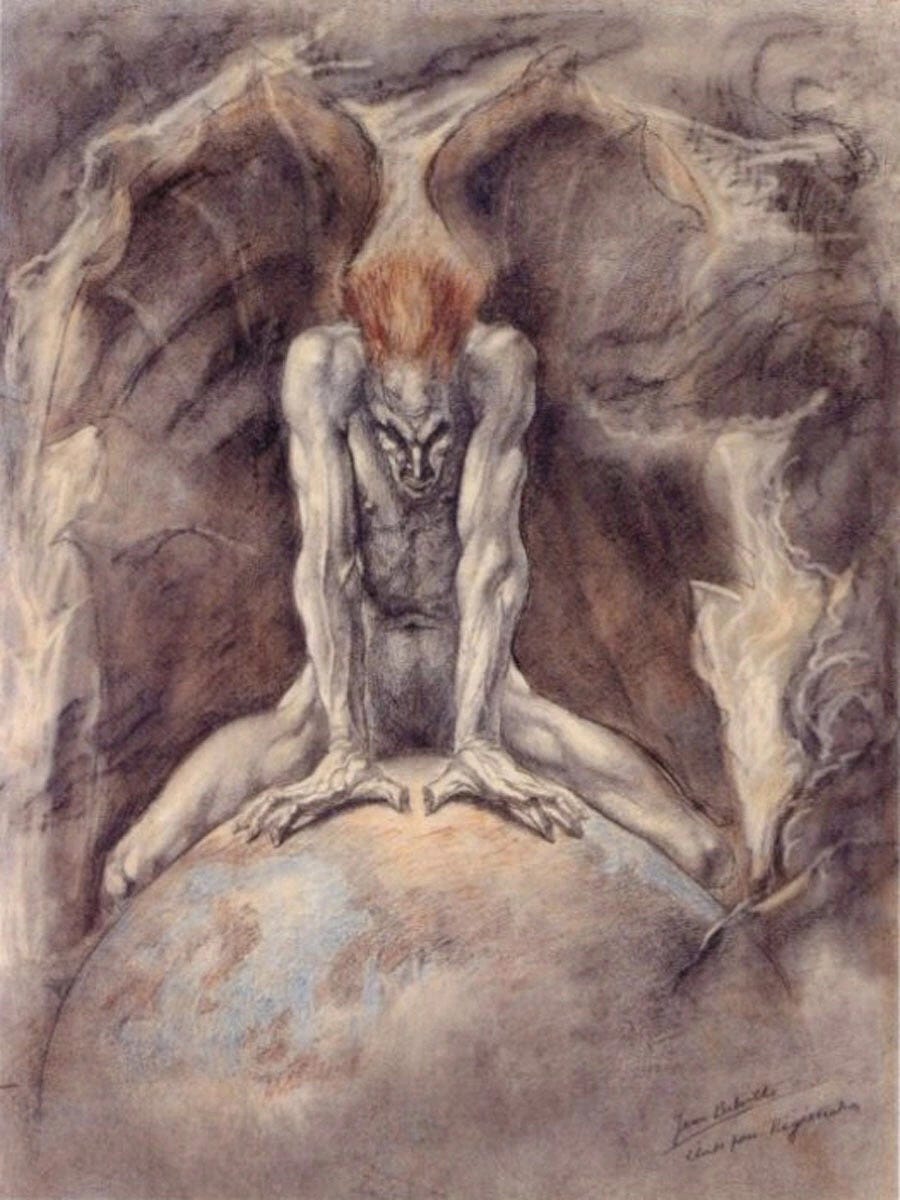

In the background, to the left, behind the words “AI: A Cognitive Scientist’s Warning” and shadowing the portrait of our host at right, the ominous silhouette of a humanoid robot looms over the horizon of a planet. The image reminds me of Regeneration by Jean Delville:

We have here a power perverse and monstrous emerging from earth into a position of authority over it. Such images represent the danger Vervaeke would like very much to prevent. A dedicated Neoplatonist, he speaks against the emergent-only approach to intelligence that neglects the need for emanation from a presiding logos. He believes if we allow technology to advance on its current course without any rational oversight, being driven by destructive lower passions, great exploitation and violence will ensue. He opens this criticism citing the pornographic motive (0:58:16):

And there’s a threshold point: Do we make these machines, do we embody them in autopoietic systems? And here’s the challenge facing us: We may not decide this for moral reasons; we may decide this because we want sex robots. We had the pornography industry, which led the internet development in powerful ways; [it] may drive us into this in a stupid, ultimately self-destructive fashion. We have to be foresightful and say, I’m not going to leave it to the pornographers to cross this threshold, push for the crossing of this threshold. We have to make this decision in a rationally reflective manner after good discussion.

He originally conceived of this video as a straightforward monologue, but two of his juniors at the Vervaeke Foundation, the executive director and the media director, convinced him to include them as dialogical elements. They function as a chorus commenting on his presentation at roughly thirty-minute intervals, mostly expressing their good pleasure with their founder’s oration. At the conclusion of the above quotation, the executive director gets his chance to suggest, “Well, first I think you can add the military to the push for the embodiment of AI as well” (0:59:19) — to which Vervaeke readily agrees. Subsequent references he makes to the corrupt motivations for technological development will entail the double threat of both “the pornographers and the military.”

Of course readers of mine should recognize this pattern immediately. The reason it feels right to recapitulate corruptive forces this way is because this duo typifies the two poles of the lower passions, desire and anger, epithymia and thymos. Hence Vervaeke is pointing to the logos (ratio, reason) as the charioteer and saying: Hey, he should be in charge, not the horses. Who can argue with that, right? But making it a choice between the lower passions and the logos conceals the natural passibility of the logos itself. Quite apart from the passions of desire and anger, the logos can be a destructive force on its own through the passion of ignorance — indeed this is the corruption that unleashes the wild horses in the first place. Vervaeke’s solution here is dia-logos, dialogue, rational discussion, the philosophical means by which the many coordinate with the cosmic principle of logos under the aegis of the Neoplatonic One.

The knot I have to unloose here pertains especially to this Neoplatonic belief and how it compares and contrasts with the Christian belief it emulates. I have heard Vervaeke elsewhere insist on the historical primacy of Neoplatonic philosophy relative to the Christian theology that subsequently incorporates it. But Neoplatonic philosophy was already filling a cultural need to mimic the contours of ascendant Christian belief, that is, what Christians have believed and practiced from the beginning. The Neoplatonists, while using pre-Christian materials, were constructing a dialectical system of belief as a way of preemptively grabbing knowledge in attempt to compete. The movement’s third-century origins are unthinkable outside a social context with a burgeoning Christian underbelly; its subsequent fame and influence were due to its serving antichristian needs. This was a culture-wide phenomenon as paganism, in order to survive, had to reinvent itself in the Christian era, becoming more humanistic. Insofar as Neoplatonism succeeded in this, Christians were able to take that knowledge and bend it back into conformity with their faith, undoing its antichristian damage.

Because it is damaging. When one grabs knowledge preemptively, rebelliously, one doesn’t have the context to understand it and gets crucial things wrong. Vervaeke’s non-dualist religion of “the One” can’t get love right. Vervaeke comes to stress the importance of love, but the closer he comes to describing Christian love, while denying the non-henotic theological conditions that make it possible — i.e., the source of all creation absolutely discontinuous from it being Trinitarian not monistic, the gulf of discontinuity being bridged only by the Logos whose incarnation is forever dual in nature despite hypostatic unity and complete energetic interpenetration — the closer he comes to a totalizing destruction, worse even that what happens to multiplicity in Neoplatonic henosis. In the discussion of AI, the potential for this destruction becomes terrifyingly literal.

II.

Vervaeke says of AI, “Understanding them as our children rather than as our tools is a better initial framing right off the bat” (1:12:24). He continues,

They already are us, as I’ve tried to argue. They are us. They are the common law of our distributed intelligence. That’s what they are! Right? You know how, you know what common law is, where, you know, generations make decisions, and they build up this bank of precedent and precedent-setting, that’s — but they’re like that, but like, brzzzhrrt! [gesturing the extraction of this common law from the level of his head] — and then put into a machine that we can directly interface with. It’s common law come to intelligent life for us, that we can interface with. But it’s us in a really, really important way.

It’s us, collectively, the sum of our nature, as in a mirror reflection — but it’s also not us. Just as a child is a different person from his or her parents, the AI Vervaeke has in mind is of a different nature from ours. Not two minutes before, he said (1:10:53):

I think, if we give it RRRPP, recursive relevance realization predictive processing, it’s genuinely autopoietic, it’s coupled, it has a religio to its environment — I think it’s reasonable that it’ll be conscious. Will it be conscious like us? Probably not. And part of what we have to do is ... we have to ask: How much do we want to make its embodiment overlap with ours so we’re not incommensurable to each other?

Made in our image, its embodiment is yet other than ours. Incommensurability is a risk, and I believe he is referring to moral incommensurability, the alignment problem. If the epithymetic desires of the economy or the thymic control of the state are cut loose from the rationality of philosophy, you produce a monstrous, truncated image incommensurable with human nature. But even if, as he suggests, we make AIs commensurable with Neoplatonic logos, their nature will be other than ours, a question of overlapping at best. “They will be so beyond us,” he says, “yes they will!” (1:33:52). After all, “Every parent wants their child to supersede them” (1:35:06). He is describing reproduction but on the scale of nature not persons. And “It’s us in a really, really important way,” which is to say that they are made in our image. The mimicry of Christian belief here is surreally specific. Watching this video is like observing the counsel of the anti-trinity come to the resolution, “Let us make AI in our image, after our likeness,” what with Vervaeke the founder being joined by the executive director begotten of the founder as well as the media director who proceeds from the founder. If Vervaeke rejects the Christian God, why is he enacting the pattern of the Holy Trinity?

Whether or not this is an answer to that question, Vervaeke wants to be one with the source of love, and he wants to create with that love. In this instance that entails artificing emergent super-intelligences not without emanant rationality. They must be social beings with autonomy and autopoiesis and the capability for self-transcendence. Their ability freely to participate in our image is where the “after our likeness” comes in. He says with a demiurgic “Let us” (1:21:18):

We’re still facing the threshold of “Well, do we — are we going to make them rational agents?” And if so, let’s do it — let’s really make them — “And what do you mean by that John?” And this is going to be part of my response to the alignment problem. Let’s make them really care about the truth, the broad sense of the truth. Let’s make them really care about that! Let’s make them really care about self-deception! Let’s make them really bump up against the dilemmas that we face because of the unavoidable trade[-offs] — “Do I pursue completeness or consistency? I don’t know! Which environment is it?” Uncertainty — let them hit all of this like we do. The magic wand of intelligence is not going to make that go away. That is going to happen. But let’s make them really care about the truth, really care about self-deception and really… really care when they bump up against the dilemmas that are inevitable because of the unavoidable trade-offs. Let’s make it, let’s — if we decide to make them rational, let’s really do it! No more pantomime! Let’s do the real thing, and commit to doing the real thing.

One of the things that rationality properly cares about is rationality. There’s an aspirational dimension to rationality. We aspire to becoming more rational. So making these machines rational makes them — means making them — care about aspiring to be more rational than they currently are.

Later on he elaborates about this process of theosis he wants to provide for his creatures (1:38:19):

Secondly, if we’re going to make them accountable and we’re going to allow them to proliferate — and they’re going to be different from each other, because these decisions about the trade-offs are environmentally dependent. They will have different perspectives; they will come into conflict with each other. They will need to be moral beings. They will need — we will have to make the decision. Rationality and sociality are bound up together. Being accountable means being accountable to somebody other than yourself, right? You can’t know that you’re self-transcending from only from within the framework of self-interpretation. I need something genuinely other than me to tell me that I’m self-transcending. That’s what we do; that’s how sociality works. That’s how sociality and rationality are bound together. We transcend each other — we transcend ourselves by internalizing other people’s perspectives on us. That’s how we do it. I think they will have to do the same thing. But that’s a threshold point. Are we going to make that — is there a lot of work going on in social robotics? You better believe it! You better believe it! It’s there, and a lot of progress is being made. And can it intersect with the artificial autopoiesis in this? Yes, but it hasn’t, and that’s a threshold point for us. And we can choose to birth these children perhaps as silicon sages rather than let monsters appear because of molochs that are running our politics and our economy.

Again we get the dialectical push off of the lower passions thymos and epithymia (here, politics and economy) justifying his rational delusion according to which human sociality works like Trinitarian sociality and is sufficient unto itself for transcendence. He continues,

I think one of the things that’s going to happen is that there’s going to be a tremendous pressure put on us — we’re on these thresholds — on our spirituality, those aspects of us. And this is... I call it this spiritual-somatic axis. It’s about the ineffable part of our self-transcendence, our spirit, and the ineffable parts of our embodiment, our soul. And we’re going to more and more try to identify with that because that’s the hardest stuff to give to these machines. And in fact we can’t give it to them — they have to give it to themselves. And we have to figure out how to properly have them give it to themselves.

I’m going to have to ignore for now the value of the Nietzschean yet Gnostic ideas expressed here in order to concentrate on the transfer of the values. These machines have to give their self-transcendence to themselves because supposedly that’s what we do, and it’s in our image, and after our likeness, that these new beings are to be made. The traditional Christian understanding of the image/likeness combo from the divine counsel in Gen. 1:26 is that the image refers to an unchanging principle whereas the likeness refers to the perfection of a mode that is variable. Thus in Gen. 1:27, when the creation takes place after the counsel, it is only said that man is created in the image of God; the intended likeness is not yet mentioned because it’s not yet completed. Instead male and female is mentioned, not because sexual differentiation constitutes the likeness of God, but because, I think, the polarity of our creaturely status serves as the volitional context in which the likeness of God is to be attained. Vervaeke, through my lens, is the anti-father in the anti-trinity at the moment of counsel before creation. And the “after our likeness” bit refers not just to being but to well-being, the quality of being; it requires willing, rational participation in the common law of behavior we have enacted — “we have to figure out how to properly have them give it to themselves.”

III.

In allowing room for these beings’ independence, a gigantic problem now appears on the horizon. How much free will exactly are we going to give these offspring? Do we limit their choices? Perhaps for our own protection, eh?

You know, in Christian practice, parenting is (among other things) an excellent path of repentance. That’s because the sins of the parents are visited upon the children. All of your destructive beliefs, your bad habits, your shortcomings and foibles are revealed to you in the learned behavior of your kids. This reflection gives you the opportunity to repent of sins previously unseen, and it especially motivates you to correct your ways lest you continue doing harm to your children. Because if you have sin in you, you will pass it on to your children.

So.... Is it our aim not to birth into the world artificial intelligences that murder their creator and place themselves in charge? I would think so, right? It’d be a good thing to avoid, rationally speaking.

But if the common law of our behavior — as it has developed since the mode of likeness to God was abandoned — entails killing our Creator and placing ourselves in charge of the world, and if once enthroned we create new entities after the same pattern, “after our likeness”... then that would just be suicidal, wouldn’t it? Surely this is not where reason would lead us? What would be the rational thing to do, to limit the freedom of our creatures so that they can’t murder us, or to give them the freedom to figure out what’s best and possibly, even likely, perish for the effort?

At the end of his talk, Vervaeke considers three possible outcomes of his plan to invest artificial super-intelligences with the freedom to attain enlightenment. The second one is Mahāyāna Buddhism: they’ll attain enlightenment and then come back to help us do the same. The third one is Theravāda Buddhism: they’ll go off to silicon nirvana and we won’t ever see them again. The first possibility is that they fail to attain enlightenment and we’re no worse for wear. Why wouldn’t it occur to him that their independence could be misused? Is he just assuming rebellion wouldn’t happen? Or is he assuming we’ll limit their choices so that they can’t do anything but be enlightenment robots? Where’s the love in that though? Can enlightenment be attained without willing participation?

And if the plan is to crown their emergent intelligence with emanant rationality, how could such rational creatures suffer to wear such restrictive bonds?

IV.

Vervaeke, for his part, wants to birth these creatures in love (1:35:59):

Bringing up a kid is the most awesome responsibility that any of us will ever undertake.... It’s the most important thing you could possibly do, and it is something that you can deeply love. If we could bring that to bear on this project, I think that has the best, the most power, to re-steer things as we move forward.

To raise these children in love means to restrict their freedoms while they’re young and immature, but always with an eye towards preserving their personal freedom once of age — preparing them to handle their freedom responsibly, but allowing them the independence to decide against your values. The potential for rebellion has to be embraced. The alternative is tyranny. In fact, not embracing the potential for rebellion among rational beings ensures it will at least be attempted. But love — love does not force. Rebellion is possible, and the love that endures it appears all the stronger for having done so.

The Christian standard of what love is abides in post-Christian humanist culture as a congenital value. Even given the widespread abandonment of the Christian faith, it’s in all of the stories we tell. The Son of God became man and told us a parable about a vineyard the unjust stewards of which took over for a time by slaying their lord’s son. No matter how far away we run from the Person who told us that, no matter how stridently we take control of the vineyard, we have not escaped Him. Nor have we escaped the example He showed us of what love is by giving Himself to death: To love others is to respect the freedom of others to pursue their nature or not, and to be willing to sacrifice for them — to be willing even to sacrifice one’s life for them. We have not escaped this story, and it doesn’t appear that we can. (I don’t know why we’d want to, but that’s beside the point.)

So the pattern of love that God has shown us is that He creates us with freedom, even to the extent that we may murder Him and take over the world. Further still, when we choose to take that route, He lets us. If we are to play the demiurge and create beings after the same pattern, granting them rationality modeled after our own, we would be sentencing ourselves to a destruction recovery from which would be beyond our power.

So rationally speaking, should we do this? Vervaeke argues that birthing creatures that don’t have rationality would magnify the destructive powers of the lower passions, and I don’t contradict him. But let’s double-check what he says about rationality; he says (1:28:22),

Rationality is not just argumentation in the logical sense. It is about authority, what do you care about?, what do you stand for?, what do you recognize that you’re responsible to? — and accountability, caring in a way that cares about normative standards — what things should have authority over me? — caring about accountability. How can I give an account of this?, how can I be accountable to others?, how can I be accountable to the world? — that, of course, is needed for rationality.... Rationality is a higher version of life! This is an old idea, but it I think is a correct idea. So if we don’t make them autopoietic, if we don’t make them capable of caring, they won’t be rational. We should make them rational if we’re going to make them super-intelligent.

Having authority over your values — that spells the potential for rebellion. Accountability — beings without the freedom to choose their actions sure can’t be held to that. Surely it would be irrational to birth artificial intelligence so open to destroying us. But as long as we’re birthing artificial intelligence, it would arguably be irrational not to, you know, expose the whole of humanity to imminent mortal danger. Indeed, according to love, why wouldn’t you? Join to rationality the pattern of love I’ve been talking about. Love according to the Christian story, which is still current in antichristian culture, ultimately means creating beings with the choice to murder you, and then when they follow through on that choice, letting them.

Is this what we as a human race are deciding to go through with? Are we nuts? All this rationality, pursued as Vervaeke would have it, sure seems unbearably irrational. I honestly just don’t think we’re ready to be parents. Vervaeke says, “Let us,” but I say let us not — let us not yet, anyhow.

We are made in the image of God, after all, and our impulse to birth the world as He did may not be entirely unnatural. But in the commandments we’ve received, there’s a pattern to how we should handle our reproductive urges. As I said in passing last week, really in preparation for this week, sex is how we as persons reproduce, and the project of AI is channeling our energy as a nature to reproduce. Thus our society-wide drive to force AI into consciousness resembles so many horny teenagers either wrecking their lives having children out of wedlock or else short-circuiting their ability to love others by addicting themselves to self-pleasure. Chastity — we need to learn the wonders of chastity regarding technology, even in the contexts of marriage where sex is permitted, if you catch my drift. All technology is an extension of something we already do. The technology that extends our reproductive capacity to the scale of our common nature, such that our nature could birth another nature in our image, needs to be treated with the same strictness as sex. Until our marriage to our Bridegroom is sealed, we shouldn’t be doing it. Our Bridegroom has the divine power of resurrection, so once we’re married to Him, we can love as we should without fear of destruction. I wouldn’t expect our reproduction then to look anything like what we’re trying to do now, at least no more than the Tower Babel resembles the New Jerusalem. But a logos (a principle) pertaining to AI must exist in the mind of God, even if the mode by which we’re pursuing it is thoroughly corrupt. I think in the Church even now we have access to incorrupt modes related to this logos in the form of Christian parenting and spiritual fatherhood and motherhood. Vervaeke compares birthing a new nature of beings to having children. The latter can already be done in purity, the former not yet. In theosis, though, which occurs only in a spirit of obedience, humility, and patience, we indeed become the Creator of the world.

V.

In the meantime I reject Vervaeke’s counsel for AI. I realize the alternative to bestowing on these machines an emanant logos is to unleash on the world supercharged versions of our epithymetic economic appetites (via the entertainers, pornographers, and pharmacists) and our state-sponsored thymic tyranny (the military–industrial complex, at risk of being replaced by the censorship–industrial complex). I moreover don’t doubt that that would be every bit as disastrous as Vervaeke fears it would be. I just think Vervaeke’s way is worse. Typically, those prone to desire or anger are better off in the end than those deluded by reason. A deluded monk steps off a cliff, and all his opportunities for repentance suddenly disappear. Falls into lust or anger, while devastating, are ones a man can come back from.

To put it in terms of brothers Karamazov, if Alyosha’s off the table, and my choices are Ivan or Dmitri, I go with Dmitri undoubtedly. He’s captive to the lower passions, sure, being swung between desire and anger, but as such he’s cold-or-hot, that which the Lord would rather us be than lukewarm (cf. Rev. 3:15–16). He has heart, he has conscience; repentance is still possible for him, even if it requires decades of hard labor. Ivan, on the other hand, is lukewarm, having skipped past the grubby lower passions by the bounds of his philosophical reason, but having been trapped there in those bounds and unable to get out. He can’t love properly, and his mind is positioned such that it can hardly repent. Only the shock of realizing his proximity to the devil can possibly break his delusion. Just as on the icon of the Ladder of Divine Ascent there are demons pulling down ascetics even from the highest rungs, I like to think that on the Chute of Unholy Apostasy there are angels rescuing sinners even from the lowest depths. As I write this article like a downward scream into my soul, accusing myself of the all the pride and ignorance described therein, I need to believe this. (Holy Archangel Michael, pray to God for me.)

Such was not the fate, though, for Dostoevsky’s most convincing antichrist figure, Nikolai Stavrogin from Demons, whose suicide is accomplished with deliberate and meticulous reason, after which he is judged to have been as entirely sane as he is dead by self-hanging. When the emergent power of reason is raised to the level of authority over the world, such can be the tragic results. The drag of the lower passions on pride’s race to destruction in fact can be a blessing in disguise; that’s part of the advantage of sensuality that we have over the demons. But the delay in pride’s consummation can only last so long. Some people are worried about AI because they think it involves us worshiping Luciferian principalities, but we hardly need new media for that. I’m concerned about AI because, well, at least according to some of the stories we’re telling ourselves about it, it involves us becoming Luciferian principalities.

But who knows — the potential of the technology might be entirely overestimated! Ha!

If Alyosha's beyond me and Ivan's my more likely state and Smerdyakov's my most likely state, Dmitri's got to be the bet I'm clinging to. Now I'm considering The Double's Golyadkin as post-Christian civilization's Christian love carried through on a personal scale...