The triadic paradigm of Tabernacle worship

The eternal pattern for approaching God

The revelation and construction of the Tabernacle, the sanctuary designed as the means by which the people of Israel interact with their God, frames the whole fifth part of the five-part structure of Exodus. A heavenly vision becomes incarnate, made of dazzling colors, gold, and precious stones, attended to by a holy priesthood garbed in wondrous vestments. As an omega-cycle, this is the descent of the heavenly Jerusalem in type.

At the heart of the Tabernacle (משׁכן, mishkan) — called also in Hebrew the Tent of Meeting (אהל מועד, ohel moed), but in the Septuagint, the Tabernacle of the Testimony (ἡ σκηνὴ τοῦ μαρτυρίου) — there is intended to be housed the Ark of the Testimony, itself intended to house the tablets of the Ten Commandments (the Testimony). There occurs some drama around those tablets, as you may recall, when Moses first tries to introduce them. The whole fifth act of Exodus, framed by the design and building of the Tabernacle, houses this drama.

The text here forms a beautiful cosmic chiasmus, with the two sets of tablets in the beta- and omicron-sections prefiguring the Old and New Covenants. The first set of tablets is written solely by the finger of God, without human participation, like the Lord bringing into being a carnally-begotten Israel. And the second set of tablets is written by God through Moses His holy one, even as Christians participate intimately in the creation of the spiritually-begotten Israel. In between the two sections in Exodus, making the covenant again possible, is the intercession of Moses, who sees the Lord face to face in a tabernacle he sets up outside the camp, even as Jesus was crucified and rose again outside the city of Jerusalem. Tabernacle is a fancy English word for tent; it applies to any dwelling that can be taken down and set up again. The temple of Jesus’s body indeed is taken down and set up again, “outside the camp.” The text of Exodus even says that Moses retires from the tent and returns to the camp, but that Joshua (Jesus, in Greek) departs not from out of the tent (33:11).

The text also says that Moses calls this tent outside the camp the Tent of Meeting/Tabernacle of the Testimony (33:7), the same name given to the paradigmatic sanctuary seen by Moses on Mt. Sinai in the alpha-section and materially constructed at his direction in the omega-section. That Tabernacle, however, is intended to be placed in the middle of the camp, to be designed according to specific dimensions, and to be adorned with art from the finest craftsmen. What is this makeshift tent that Moses himself sets up outside the camp, with no specified dimensions, and why is it given the same name? The Septuagint here actually says that Moses moves “his tent” outside the camp, and then drops the articles from the name that Moses gives it, helpfully saying that Moses calls it not “The Tabernacle of the Testimony,” but “(a) tabernacle of testimony” (σκηνὴ μαρτυρίου). The Greek use of articles does not at all match English one-for-one, but, suffice to say, a different kind of identity is nonetheless expressed, allowing for a certain typological relationship between the tents, like when we call Jesus’s body the/a temple.

With regard to the text (of the fifth part of Exodus), consideration of this typological connection yields the same pattern as the cosmic chiasmus. The paradigm of the heavenly Jerusalem is revealed in the cosmos in the alpha-age of creation; its full materialization occurs in the omega-age of the final judgment. In between them, in the chi-age, the center of the Day of the Lord’s planting in time, Jesus hangs upon a cross outside the City. On this Cross, like a makeshift tent, is found the chiastic cause of the alpha and the omega. Everything descends down from it, like rivers from Paradise.

Likewise, the intended materialization of the paradigmatic Tabernacle, revealed on Mt. Sinai in the alpha-section, is able to occur in the omega-section of the story (for the distinction between the everlasting Tabernacle pitched by the Lord and the one that was constructed by man, see Ex. 25:8–9 and Heb. 8:1–2) because of Moses’s Christ-like face-to-face intercession with God in the chi-section, in a tabernacle of testimony that has to be set up outside the camp because the people have befouled themselves with idolatry and fornication. The textually-central tent is worthy of its name because it’s the chiastic cause of both the reality and the manifestation of the Tabernacle of Testimony. The very purpose of the paradigmatic Tabernacle revealed in the alpha-section is the communion with God enjoyed outside the camp (outside this world, typologically) by Moses in the chi-section — which then in turn facilitates the full materialization of the Tabernacle in the omega-section, which of course also has the communion with God in the chi-section as its purpose. I’m rehearsing this whole pattern so as to reinforce what we’ve learned about the cosmic chiasmus. But aside from the chiastic causality, there is not to be forgotten a linear, historical causality. Hence, the capital A-B-A’ of Genesis–Christ–Apocalypse has within its middle a fractal triad pattern of lower case a–b–a’: Law–Christ–Church (played out in the drama of the tablets). So there is a larger pattern of being, well-being, and eternal-being, and contained within the human drama of well-being, there is nested a threefold sequence, patterned after the same and allowing for volitional human participation in the divine.

But being, well-being, and eternal-being work as somewhat of a horizontally linear triad. There is a vertically linear triad expressing the typical manner of human participation in the divine, which we saw through a patristic lens in a previous article, drawing from the Hellenistic expressions of purification, illumination, and perfection — or practical philosophy, natural contemplation, and mystical theology. That language, however, based on the hazy intuition of pagan Greeks possessing only the natural law, is merely used as the apostolically-tailored translation into Greek of original Christian Pentecostal experience based in Old Covenant religious practice.

Purification, illumination, and perfection

When Evagrius of Pontos — a learned disciple of many saints who in the late fourth century sought and received much ascetic wisdom in the Egyptian desert — sets out to write on the topic of practicing the life in Christ, the praxis of the virtues, he places it in context as the first rung in a threefold program. “Christianity,” he opens his

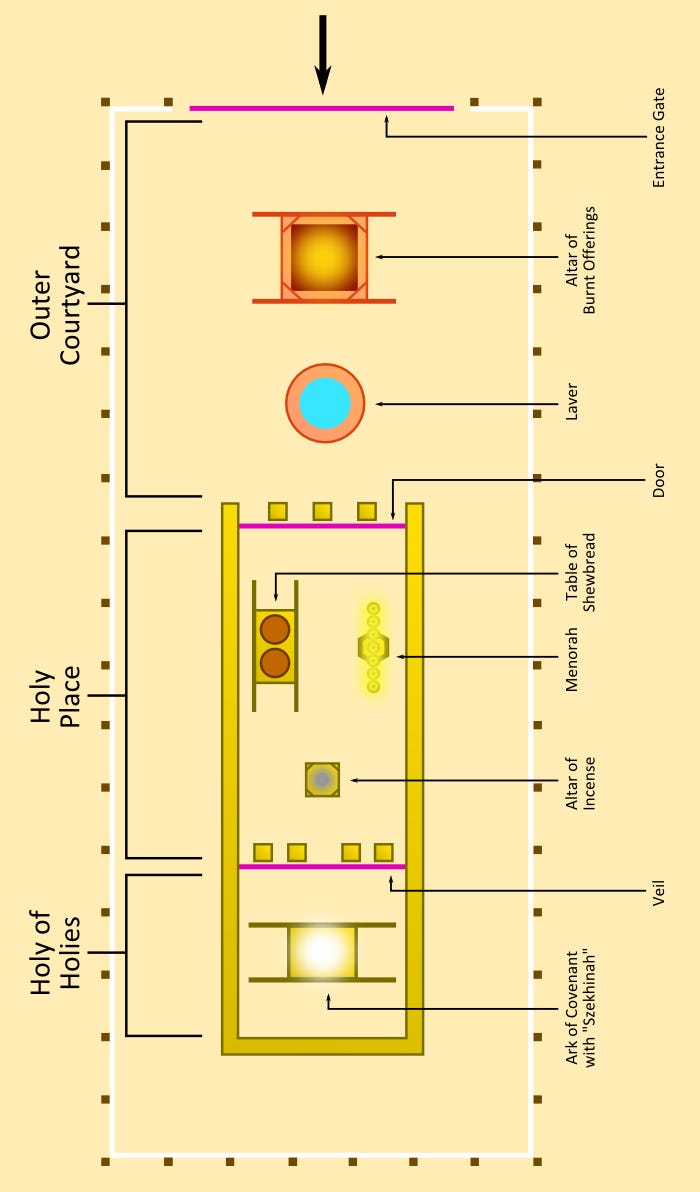

We saw in that article, via the spiritual eyes of St. Maximus, how this triadic sequence is embedded temporally in the Old Covenant in the weekly observation of the sixth-day preparation, the seventh-day sabbath, and the eighth-day beginning of a new cycle of time. But it’s embedded spatially in the pattern of the Tabernacle of Testimony at the center of Israelite worship, as first revealed in a heavenly vision to Moses on Sinai. The pattern of the Tabernacle is eternal; it’s “true” as the Epistle to the Hebrews calls it (at 8:2), which means it does not change and is ever-present in creation. It’s the eternal pattern by which man may approach God, in any context. Traditional Christian churches, because of their Pentecostal perspicacity, manifest it even more lucidly than did the Israelites in the desert or the Judeans at the Temple in Jerusalem, though it is faithfully visible in all three. The pattern is threefold, which comes across plainly in its description in Exodus. It does not yet come across in the shape of the text of Exodus, which is predominantly pentadic, but that will happen (in Leviticus). Here is the ground plan as expressed in the Torah, with all the gates facing east:

The east is where the sun comes from, which is above, so the best symbolic representation of the tabernacle floor plan places the east at the top, as I have it here (all maps, really, should have the east at the top). The Holy of Holies housing the ark of the testimony sits in the westernmost part of the Tabernacle, which is to say the lowest part. It’s like a cave in the earth, or a tomb, pointed towards the light of the sunrise as to the star of Bethlehem, or to the divine power to resurrect Adam — prefiguring both the Incarnation and the Resurrection. In Tabernacle worship, threefold linear ascent is achieved inversely through descent. But I’ll continue here describing the movement as ascent, allowing the natural flow of the page to represent the downward east-to-west motion. Those three parts:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Cormac Jones Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.