Two Psalms

Fifty and Sixty-nine, namely

I’ve been preparing to lead a day-long Advent retreat at an Orthodox parish next month on the topic, broadly assigned, of literary structures in Scripture and their incarnational meaning. The event has given me the opportunity to take stock of what all I’ve done in outlining books of the Bible — and more so, what all I haven’t done. The Psalms are an area of neglect that I should probably pay more attention to because there is so much pedagogical benefit to be had there. I’ve long had an outline mapping the whole Psalter on a macro scale; that’s public on my website. But I’ve never committed to outlining individual psalms on any kind of comprehensive scale. I’ve just done a few here and there. Commenting on them would be such a gargantuan task, requiring a whole book, I always figured if I ever end up doing it, it would be as an old man with more spiritual maturity than I have now. In general I’m in no rush, and I prefer it that way. But also, perfectionism is a lame excuse for not doing anything. Looking at the matter today, I figure at least mapping the psalms out should be a task I engage in more actively. Here are two important ones to get the ball rolling.

Psalm 50

The most commonly recited psalm in the Orthodox Church, Psalm 50 documents King David’s repentance after bedding Bathsheba, killing Uriah, and being convicted of these sins by the Prophet Nathan. It might be hard to see now, looking back at history, but I believe this repentance on behalf of David stands as the most innovative and paradigmatic shift (of the positive variety) in man’s relationship to God apart from the work of Christ Himself. Who before David begs for mercy from God like this? Having done what he’s done? The Lord had told Moses in the Torah, “I will have mercy on whom I’ll have mercy” (Ex. 33:19), so would anyone previous to David have even thought to ask God for mercy?

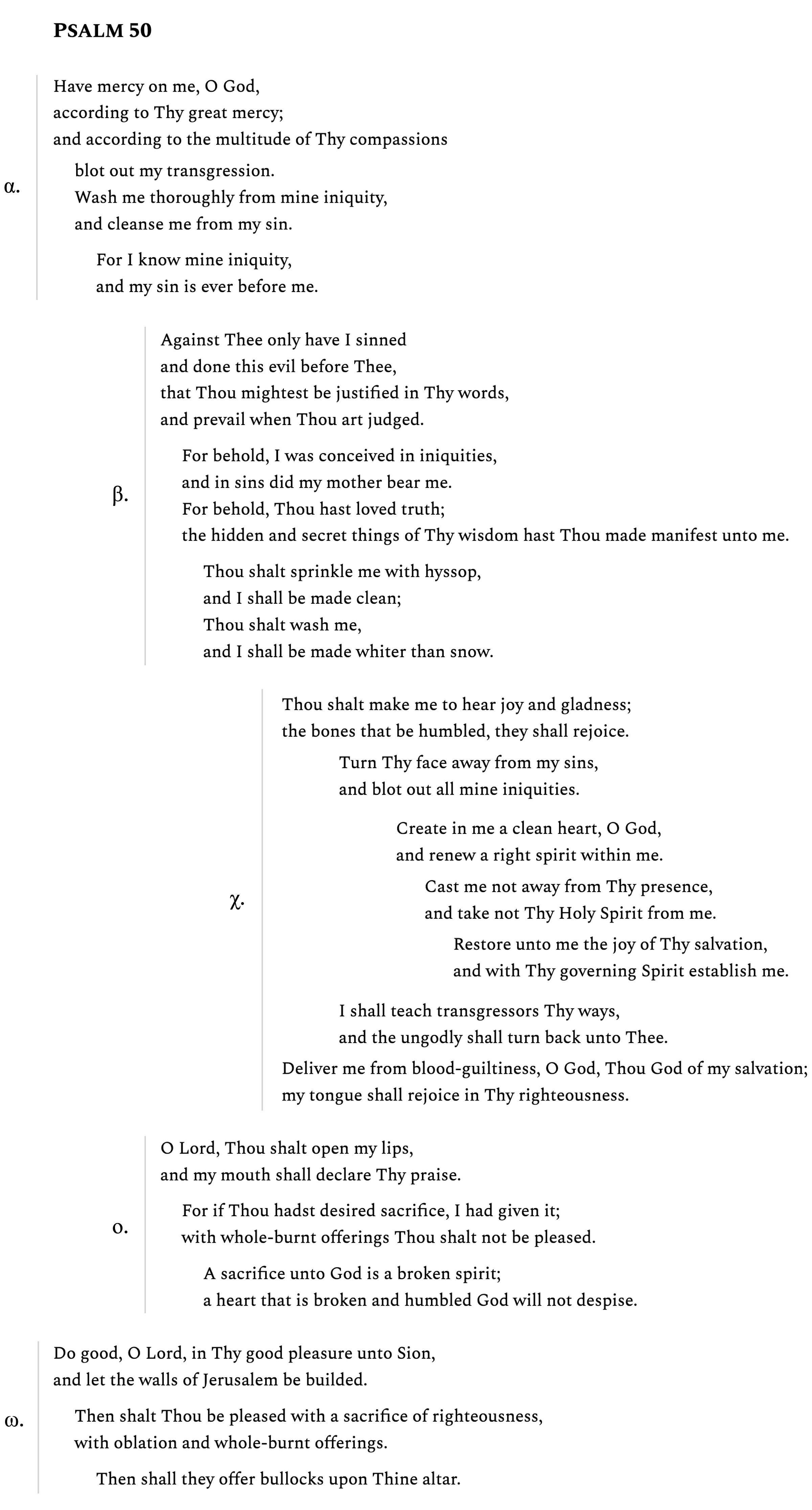

The structure of the psalm flows chiastically out of a powerful threefold invocation of the Spirit in the center of the center. The rest of Scripture has taught me to be receptive to triadic centers, and “renew a right spirit within me” / “take not Thy Holy Spirit from me” / “with Thy governing Spirit establish me” is too conspicuous.

Reader Donald Sheehan doesn’t see it though. In his posthumously published book The Shield of Psalmic Prayer (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2020) — which I recommend to others, valuing it very much for its piety and poetic sensibility, although I frequently disagree with his arrangements — he sets the psalm as a long-range chiasmus, a nineteen-part palistrophe. Palistrophe is another word for chiasmus, and I like to use it to denote big, long structures. Sheehan’s Psalm 50 (pp. 81–82), being nineteen parts long, is centered on the tenth verse, “Create in me a clean heart, O God, / and renew a right spirit within me,” the first of the three invocations of the Spirit. That means he has the second two invocations inversely paralleling the two verses before the triad, and in effect the triadic mention of Spirit has no structural meaning in his eyes.

I’m not partial to these long-range palistrophes, common in chiastic studies. I don’t think the mind retains information efficiently enough to keep track of the parallels in such long sequences. They look impressive in print, but aren’t practical when it comes to encoding them in memory for free-flowing recital, on the reader’s part, or, more commonly, when it comes to listening comprehension. To use a latter-day metaphor, there’s not enough data compression. Short, iterative patterns that repeat in layers like a fractal are much more accommodating to the human mind. Though in many ways digital technology is obliterating human experience, I think in many other ways (which we would do well to cling to), the hacks of digital technology are actually bringing us back in wavelength with ancient patterns of perception lost in the flood of modernization.

That’s my arrangement of Psalm 50. Look at the part labeled β. Those verses parse into a triad of coupled couplets very simply and intuitively. The mind, on a microscopic level, clings to couplets, like DNA to the double helix structure. Look at the double “behold” structure, contrasting “I” and “Thou”; it’s a couplet of couplets, a couplet fractal. In a long-range palistrophic setting, not just the central triad, but each of these little coupled couplet structures is broken up and unaccounted for, which just doesn’t reflect the way that we experience the psalm.

But let’s zoom out and look at the whole pentadic structure. Each of the four parts around the central chiasmus makes most sense as an ascending triad, reflective of the chiastic center of the chiastic center. There are perhaps other ways to see it, and some readers may prefer a different arrangement. The first part, α., definitely makes sense, perhaps the most sense, as a couplet cubed, that is, two stanzas each consisting of two couplets (2 × 2 × 2). But it also clearly makes sense as a triad (3 + 3 + 2, reflecting the rhythm of 2 + 2 + 1 in ω.), and at this party, everyone else is wearing a triad costume.

But that the party itself is pentadic in shape seems very clear to me, with the chiastic center reflecting the pentadic housing around its own triadic center — and the relevant pentad certainly appears to be a chiasmus rather than a ksiasmus, with the “heart that is broken and humbled” in ο. resolving the “Against Thee only have I sinned” in β., and the pleas for a merciful blotting out of transgression in α. culminating in the building of the walls of Jerusalem in ω.

As for the chiastic center, at the start of χ., the humbled bones which shall rejoice announce death-and-resurrection typology we are accustomed to centralizing. The physical image of rejoicing bones in the local alpha-line is then matched with a rejoicing tongue in the omega-line, about deliverance at last from the retributive cycle of blood-guilt (for “shall rejoice,” the Hebrew in these two verses has different synonymous words, whereas the Greek has the same word). Then the pleas for an exodus from sin in the beta-line is matched in the omicron-line with the conversion of transgressors to the ways of the Lord, as when the Gentiles turn back to God in the Church.

It all centers around the threefold mention of Spirit, indicative of the triadic shape of our union with God (see last week’s article), which the sinner King David innovatively sees — with hope against hope — as potentially restorative.

Psalm 69

Not everything is chiastic! Commonly when I read people writing about chiasms in literature, it appears obvious that they only found a chiasmus because they were looking for one. It’s a “they picked up a hammer, and now all the world’s a nail” kind of thing. The objective should be, especially with Scripture, to listen to the text and be open to whatever form its meaning takes. Sometimes a chiastic structure makes the most sense of the meaning of the text, but oftentimes it does not.

The most elementary form of biblical structure, as I’ve been mentioning, is the couplet, two consecutive lines that can relate to each other in different ways. Their juxtaposition can represent a reiteration, an inversion, a reversal, an intensification, a generalization, or any number of other ways two things can relate to each other. When this form expands — well, first of all, the couplet can be a simple fractal of itself, as in Psalm 116,

It’s a couplet of couplets, structurally nothing more. This is the whole psalm, so there’s no other material anywhere to bend this into a more complex structure. You can’t make a pentad out of it. If you see in your translation of the Masoretic text (where it’s numbered 117) a “Praise the Lord!” at the end, that’s just the “Alleluia” inscription meant for the next psalm (Psalms 110 through 118 all have this). No, it’s a couplet of couplets, and there’s nothing even especially chiastic about it on the whole. I suppose the second verse gets a little chiastic in its Hebrew syntax, in that mercy (chesed) ends the first line and truth (emet) begins the second line, but the four lines of the psalm go A–A’, B–B’, not A–B–B’–A’. Not a chiasmus.

But when a couplet expands, say into a triad, or when a fourfold fractal couplet expands into a pentad, what you get is not necessarily chiastic. A triad can be a linear progression. In a pentad, the four verses around the center can relate to each other in direct parallelism, rather than the inverse parallelism of the chiasmus. This of course is what I call a ksiasmus, based on the shape of the Greek letter Ξ rather than Χ, which I explain in “The Cosmic Chiasmus.” The pattern is A–B–Ξ–A’–B’, rather than A–B–Χ–B’–A’. Just as the two lines of a couplet can be a reiteration or an inversion, so the two sides of a pentad can be directly or inversely parallel. If your hermeneutical mind is not receptive to the difference, the literary shape of certain texts will elude you, especially as you negotiate different fractal layers.

With Psalm 69, we have the fractal couplet expanding into a pentad, but it’s ambiguous whether it’s chiastic or ksiastic. Here directly below we have a chiastic arrangement, which keeps the couplets together as undifferentiated units. From the Greek:

That’s a very coherent “cosmic chiasmus” pattern, and very useful as such. But, as indicated by the indentation, there are parallels being drawn between the individual elements of the couplets that the chiastic symbolism doesn’t capture. Also, there’s a fivefold structure of “let them” verbs in the middle that also is not recognized. That’s why I prefer the following ksiastic arrangement. The words are very much in the same setting, but the symbols adjust one’s vision of the fractal layers as well as identify the parallels between the lines within the couplets. There’s a pattern of direct parallelism here, one that seems meaningful for a psalm that is desperate not to circle back on itself, but to look beyond itself, even while inescapably remaining within itself.

For if Psalm 50 is the epitome of repentance, Psalm 69 is the epitome of the fight against vanity. I treasure this psalm very much, and apparently so did the ancient desert fathers of Egypt. St. John Cassian reports in his Conferences that among at least certain monastics of fourth-century Egypt, the first two lines of this psalm — “O God, be attentive unto helping me; / O Lord, make haste to help me” — were used for ceaseless, circular prayer of the heart, like the Jesus Prayer that you read about in other ancient sources.

The psalm’s pleas for help mount towards a climactic volley against the demons of vanity, spouting, “Let them be turned back straightway in shame that say unto me: Well done! Well done!” Let me tell you, for those suffering from vanity, these are the most precious, most powerful words — with its words inspired by the Spirit, the psalm itself is the help the psalmist is begging for! You want mercy? This is what it looks like. This is what it feels like. And it is glorious.

That’s the center. That line (ξ.) is the third in a pentad of “let them” verses, and it’s pivotal. After that line, punishing the source of our duress, we may say instead (ο.), “Let them be glad and rejoice in Thee all that seek after Thee, O God.” The seeking here parallels the enemies seeking after the psalmist’s soul in the first “let them” verse (α.), according to a ksiastic pattern — with, moreover, the desire for evils in the second verse (β.) being countered with the love of the Lord’s salvation in the fifth verse (ω.).

The ksiastic shape is reinforced when you zoom beyond the “let them” verses (ξ.) and see two lines on either side that parallel each other directly and not inversely — or at least that distinction is clear in the Greek. I’m Orthodox Christian, so the Greek text of the Old Covenant Scriptures, which happens to be the oldest complete manuscript tradition, is my heritage, my starting point. The later Masoretic text of the Hebrew (which we’ve already seen messes up the inscriptions in Psalms 110–118) along with more ancient witnesses like the Dead Sea Scrolls comprise essential resources, as I duly recognize that texts like the Psalms were originally written in Hebrew, even if the Hebrew texts that we have are imperfect witnesses to the Second Temple renditions of texts many of which originally existed in a different, earlier form of Hebrew. At this point in my consideration, though, I realize the impossibility of identifying an original text and just return to what has been handed down to me by a tradition I recognize as Spirit-filled. That would be the Greek — specifically the Greek Psalter I bought in Greece, but also all the other resources I can get my hands on.

But I still reference the Hebrew to glean what I can, and in the case of Psalm 69 all these textual discrepancies are doubled because the whole psalm is excerpted from, or is incorporated into (depending on which psalm came first), a much larger psalm, Psalm 39, where it comprises the concluding section. The basic shape is identical, but the words are different, both in the Greek and the Hebrew. To look just at the Greek of Psalms 39 and 69, you might think that two different translators produced two different translations of the same thing — but to look at the Hebrew that we have, you might get the same impression! Now, the Psalms originally had musical accompaniment, so it’s not so outlandish to think the wording might have been altered to fit different musical settings in the two psalms. But again, what’s the original text? It would appear the original would be whatever the Holy Spirit says it is, and that can be different in different times and places. The wind bloweth where it listeth. The meaning of the words, and their great spiritual utility, remain unaltered by the textual differences (and, seemingly, by the removal from its musical context), and that in itself is plentifully instructive. Literary form is not the objective of prayer!

Insofar, however, as we the detritus of history can really use study of literary form to begin to rediscover the meaning of words made hollow by the idolatrous abuse of language, I do care about these things. I accept that the differences between the Greek and Hebrew, in both Psalms 69 and 39, frustrate our ability to nail down a single outline of Psalm 69, authoritative for all comers. The ksiastic identity of the five interior “let them” verses at least is stable between the different versions. But the structural relationship between the first and last verses of Psalm 69 is in question. If we agree on the Greek, we’re fine. If we agree on the primacy of Psalm 39(40), we’re fine too, even in Hebrew, where the structure visible in Greek is intact. The problem is with the Hebrew of Psalm 69(70), where the structure doesn’t hold.

To explain what I mean, let’s first consider just the Greek version of Psalm 69. That’s the text reflected in the English translation outlined above, which I’ll place here again to reduce scrolling. (See? Scrolling. Digital technology really is resurrecting some ancient modes of noesis.)

The condition of being poor and needy (ο.) explains the need for the attentive care requested in the opening line (α.). The intensified request that haste be made in the second line (β.), meanwhile, is followed with the final line, “make no [long] tarrying” (ω.). And the ksiastic shape of these lines neatly reflects the ksiastic center (ξ.).

However, in the Masoretic text of what there is numbered Psalm 70, for starters there is no word present for what is translated from the Greek as “be attentive”. There is a similar word there in the Masoretic equivalent of Psalm 39 (what there is numbered Psalm 40), but it was either added there or taken away when excerpted as Psalm 69(70). It would appear the Greek translators either had that Hebrew word there also in Psalm 69, or else they made an interpolation based on Psalm 39. As is, Hebrew Psalm 69(70) begins something like, “O God, to deliver me, O Lord, to help me, make haste” — whereas Hebrew Psalm 39(40) reads as “Be pleased, O Lord, to deliver me; O Lord, make haste to help me.” The latter is still shaped like a couplet, but the former not so much. Grammatically it’s more like a single line, and even if you were to break it up, it would be unclear why the first part, “O God, to deliver me”, would be parallel to either of the lines in the last verse, on the other side of the central ksiasmus.

Speaking of which, in the omicron-line of Psalm 69(70), rather than what is translated from the Greek as “come unto my aid”, from Hebrew it’s “make haste unto me”, which muddies the ksiastic correlation between the making haste at the end of the first verse and the “no tarrying” at the end of the last verse. This formal disruption doesn’t occur in the Hebrew of Psalm 39(40), where it has something like “the Lord takes thought for me” or “the Lord will account it unto me.” Really, as far as Psalm 69(70) in Hebrew is concerned, since the first couplet isn’t really a couplet, the psalm loses its pentadic shape altogether, which is unfortunate — and which isn’t even the case in the Hebrew of Psalm 39(40), where it’s still pentadic. It’s reasons like this that I really appreciate the Greek version of the Old Testament.

But, really, it’s the living tradition of the Holy Spirit that I prefer. These words — words, words, words.... Insofar as they are created things, mere human rhemata (ῥῆματα), they are included in the indictment of the Preacher when he says, “All is vanity” (Eccl. 1:1–2). Vanity — as in, emptiness, creatureliness. It is the Creator alone that gives life, and it is for Him and His energies, His words, His logoi (λόγοι), that I yearn. Without Him all is vanity. But when He fills our words with His life, the vanity is abolished, the purpose made clear, and that which has been created is united to the Creator in an ecstatic, merciful, and everlasting love. That’s why we pray the Psalms!

Very good, and I am very much looking forward to the retreat.

Umm, Cormac? Isn't this Psalm 51?