‘Waiting to Hold You’: a screenplay

This year for Christmas, I’m just releasing the whole thing

Merry Christmas to all my readers, most of whom will be within the twelve days of the feast when this is released on New Year’s Eve. I, however, observe the old calendar and am yet a week away from the Nativity. ’Tis the season nonetheless: Merry Christmas.

I’ve often said the worst thing you could do to someone is ask them to read your screenplay. When the Antichrist appears, I’m certain, you will recognize him when he asks you to read his screenplay. Well, don’t worry, I’m not asking. I’m just putting it out there — to be largely ignored, no doubt, but it’s time. I knew going in that there was never any hope that this, my dream project, would ever be produced. I had no hope, sure, but I had a dream. There was a time when that dream played a useful role in my spiritual life. Through the creation of cinematic narrative I could embed all my ideas cultural, philosophical, theological, historical, and structural in the context of human experience so as to subject them to the priority of relationships with others, the commandments to love God and neighbor, even if in an artificial medium. Now, the fantasy of participating in filmmaking, present in my soul if not terribly active, provides nothing positive towards my Christian purpose. If anything, it’s holding me back from advancing in a life of virtue by generating a background hum of epithymetic desire, contributing to my egotism. Time to turn a page, time to cut it off. The dream is worth more to me now as a sacrifice.

But this screenplay I created, I still cherish it very much. I felt in times past like it was a child, one I mothered and was responsible for raising. Raising a screenplay would mean getting it an education and preparing it to have a life in the world beyond oneself. Well, I’ve failed at that. Maybe it was more like a horse than a child, one that I’ve kept in a barn. I haven’t found a place for it to live and can no longer afford to keep it fed. Releasing it into the wild is the very least I can do. Maybe it’ll find a way to survive on its own. There’s a non-zero chance, after all — whereas if I keep it locked up, there is 100% certainty it will die and do so as soon as possible. But maybe that metaphor’s not right either. There are no horses in my screenplay. Maybe it’s less like releasing a horse in the wild, and more like placing a seeded fruit on a curragh and pushing it out to sea.

So, for any of you gulls out there, circling the coasts of electronic reading material, here’s a pdf file to download, if you so wish:

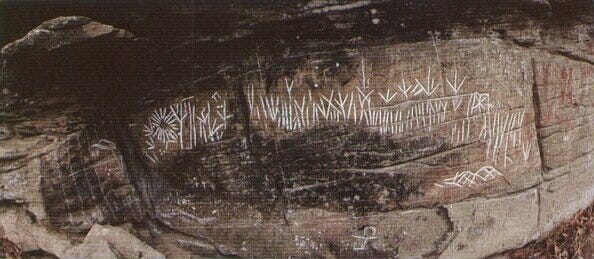

And this is what you’ll find if you do: a drama taking place first among monastics (a small men’s community and a small women’s community) in ancient Ireland circa 690, and then among Irish American teenagers in 1990 West Virginia. The ancient petroglyphs in West Virginia that I’m so fascinated by — having written a long personal essay about them twenty years ago (see “Man from West Virginia” available on my website) and having again visited them this past year as documented here in this Journal — provides the loose connective tissue between the two stories.

Knowledge that these petroglyphs are at least partially Irish in origin is speculative and not at all certain, so the screenplay makes no claims regarding this. The impetus of the Irish part of the story, rather, is to explain why I think it was that so many monastics during this historical era fled Ireland. The original flowering of monasteries in Ireland occurred starting in the fifth, but mostly in the sixth century. By the end of the seventh and into the eighth century, a flowering of Christian art occurred, but concurrently with a lot of monastic corruption. There were no towns in ancient Ireland; it was entirely rural. When all these monasteries sprouted up, at first they were very countercultural, as monasticism always is in its origins. But as they became institutionalized through the generations, and ingrained in the culture, they began to play the role of towns and were corrupted by secular ambitions. In some monasteries, the abbacy would be passed down from father to son, which is not how monasteries are supposed to work. This is not just a cute facet of Irish Christianity but a corruption of original purpose. As I said, there was also a tremendous artistic flowering at this time — I refer to the famous illuminated manuscripts and high crosses that were made in the century before the Vikings arrived in 794 — but the royal patronage that made all that art possible came with a lot of downsides. The original monastic impulse persisted among Irish Christians, but they were continually finding their monasteries diverted to other purposes. Those who still longed to renounce the world for Christ had as an outlet the tradition of floating monasticism and “white” martyrdom established already in the sixth century by the likes of Sts. Brendan the Voyager and Columba of Iona. (For the meaning of white martyrdom, see my post on St. Cormac of the Sea, disciple of St. Columba.)

So the Irish part of my story ends where our certain knowledge of that history ends: floating in the North Atlantic Ocean. That was a long, long time ago. I then pick up a modern tale set in 1990 among the teenage descendants of Irish immigrants to America so as to explore all the majestic tragedy that has occurred in our exile from our deep Christian past. This West Virginian half of the movie turns out to be much longer, but there’s a reason for that. In outline form, I’m actually telling the same story twice, just in two radically different moral and historical contexts. The Irish story I conceived as a kind of paradise narrative. It only admits good; all evil is banished to the margins and occurs off-screen. There’s a central monastery in the lives of the characters which functions as a source of corruption, but no scene of the movie occurs there; it’s only ever mentioned in dialogue. Postmodern dialectical storytelling cannot possibly craft such a paradise narrative. Where’s the conflict, right? How can this at all be interesting? Well, the interest is in following the characters progress through a painful but rewarding journey of divestment and spiritual advancement patterned after the schema of purification, illumination, and perfection. The whole Irish story is a triadic fractal patterned after these spiritual principles (like the Book of Leviticus or the Gospel of Luke, in my estimation).

Then the West Virginian story repeats the whole outline, except it exists in exile from paradise; its oikoumene narrative admits evil modes of purification, illumination, and perfection alongside the good modes (oikoumene is the Greek word for the world we inhabit outside paradise). The chaff grows alongside the wheat. This complication causes the story to be much longer than the paradise narrative of the Irish story, but actually they have the same overall shape. It’s a diptych. And the purpose is to depict the pain of exile in myriad fractal ways, the unrequited love that burns in the heart when we are separated from our home, our source of being.

Thus the West Virginian half of the movie is a love story, but it’s a break-up. It’s about all the lust and anger, violence and desire, that tear us away from all the beauty, goodness, and truth the pathways of which we still trace with our lives and can feel is our real purpose. It’s not just a matter of remembering a paradise once experienced. It’s more present than that. It’s like the very outline of the story we are living depicts the image of a Bridegroom from whom we have been separated. It’s about being everywhere in the presence of God and yet being kept from His embrace by the iron restraints of sin and death. Yet within this exile, within this superposition of paradise-form and exile-content, there is an opportunity extended to us for repentance, for resolution of vexation, for the requital of our love. There is hope for return.

The script’s current length is 219 pages (in screenplay format). As I’ve said, that’s the size of two movies. So on page 99 there’s a break, space for an intermission. That’s not the division between the Irish and West Virginian stories, however. The Irish story finishes on page 60, leaving the rest of the script for West Virginia. You actually wouldn’t want an intermission at the meeting place between the two stories because the transition between them is the sweetest and most essential experience of the combined narrative. The movie on the whole really is a love story (largely unrequited) between its two narratives. But the narratives are both in three acts, and the intermission occurs between acts one and two of the West Virginia story. I mention all this because I think, due to the length, it’s helpful to know the parameters of what you’re getting into and what you should expect — should any gull out there ever choose to snatch this fruit up, maybe even to deposit its seed in the fertile soil of some foreign land. Sadly, as I write this missive on the edge of the year of our Lord 2024, the soil of my land is spent.

This journal is for my writings, made available for anyone who wants to read my writings. Well, here it is, my favorite thing I’ve ever written, Waiting to Hold You.

Oh, and one of the joys of writing a screenplay you know will never be produced is that you can write into it whatever music you like without ever having to worry about paying for the clearance rights. The West Virginia part of the movie employs a number of songs that, for your convenience, I’ve placed in a YouTube playlist here.

Oh man, the first part of this is so beautiful and I mean - really something. I haven't got to the modern part, but the first part is doing a great job of making me not want to leave, causing me to feel like there is something ahead that is going to ugly up the beauty and simplicity of the first part with complexity and dissonance. I honestly just feel like...ugh. I don't want to go from this part, I just want this part to fill up the whole film. Ha! Too bad...but I grew up in the 90's so maybe I just have this feeling that ugh, I know what's coming - but then so did the monks when they got in the boat to head West. So I suppose we have to go with them into death with the same dread/hope. Now, the part where the nuns walked together with this sense of "...being alone with you, what will it be like?" and they talked about being soul friends - well. Up to this part the whole beginning was a tension of beautiful things, and this moment with the nuns had me weeping - it reminded me of me and Jared, especially when she says "But we have to stick to virtue" - ah! So I was in tears on the couch - Jared looked over at me and was like "something really had an impact". Lol. Now I will definitely have to follow this all the way through. I really really hope this does become a film some day - hopefully someone will make it beautifully. I'll say something more when I finish the whole thing. Thank you for sharing this with us, it really is beautiful.