What’s the earliest octave in the text of the Bible?

Do musical scales have anything to do with it? What about decads? And is the Apocalypse of Weeks in 1 Enoch of any relevance?

The question occurs to me: What’s the earliest octave in the Bible? I’m not just looking for the suggestion of the octave or the meaning of the octave, but an actual in-the-flesh literary structure. My earliest recognition of the pattern came from trying to figure out the structure of the Psalter, and I’ve always wondered if the literary shape were related to the musical scale. Psalms are song lyrics, and the Psalter is a mixtape. Whoever edited the Book of Psalms I believe did so according to musical principles. Now, I am in way over my head whenever I speculate about musical theory or the history thereof, but the ideas are so attractive I can’t but strive to understand them. Here, though, I merely consult the field of music in attempt to understand literary structure. Extending what I’ve learned from King David to the Books of Moses, I ask, What’s the earliest octave in the Bible?

The Hexaemeron?

Where else to start looking but “In the beginning”? The six days of creation in Genesis 1, I think, conform first of all to the pentatonic scale, rather than the heptatonic scale related to the octave. As I explore at the end of “The Cosmic Chiasmus,” the first five days of creation comprise a ksiasmus which is then circumscribed by the sixth day after the fashion of a Celtic cross. This sequence accords with a pentatonic scale resolving in a sixth note, again the tonic but at twice the frequency — what we heptatonic supremacists call the octave. A pentatonic scale covers the same interval as the heptatonic, but with two less notes. It derives naturally from the overtones discoverable in any note and is widespread in ancient cultures across the globe. Numerically, it is the common scale of all humanity.

Like a pentatonic scale, then, the first day of creation resolves in the sixth. Between the heaven’s circumscription of earth on the first day and the way man is given to rule material creation on the sixth day, we have an image of the same tonic spread an “octave” apart, though here a “sextave” apart would be a more numerically appropriate expression. The two renditions of the tonic, I think, even reflect the polarity of male and female — physically, in that men’s and women’s voices are naturally an octave apart on average, despite being equally contained within “adam” — and symbolically in that the first day’s repulsion from non-existence corresponds to the sixth day’s attractive, sensory encompassing of creation, according to the pattern of thymos and epithymia. Contemplating sex this way, according to the sextave of the pentatonic scale (pun unintended, and etymological connection non-existent), I think offers an opportunity of understanding the biblical story of woman coming from man in a meaningful, non-sexist way. The biblical conception of sex is as natural and harmonic as the root and sextave of a pentatonic scale. In other terms, our thymic repulsion from non-existence comes prior to our epithymetic embrace of creation. In more numerical terms, before you can embrace the relations of the one and the many, you first must move from zero to one.

But of course none of this text in Genesis is yet ogdoadic in the way that we’re looking for. The whole reason I’m mentioning it is discovered with the addition of the seventh day, the sabbath, which transforms the pentatonic understanding of what precedes it by suggesting the heptatonic scale present in the ancient Near East. Not only did God reveal to Moses the cycle of seven days, but heptads were also popular in Mesopotamian and Greek cultures, musically as well as cosmologically. If pentatonic is the common scale of mankind, the heptatonic scale, derived from the interwoven sequence of tonic and dominant (the circle of fifths), appears to play a more priestly role.

And the heptatonic scale resolves in an octave. Musically speaking, the seventh day begs desperately for an eighth. The structure of the creation account in Genesis, however, contents itself with mere implication, including no eighth element resolving the sequence. Rather, I believe, the sabbath is used structurally as a ksiastic center between the two creation accounts in Genesis 1 and 2 (as I discuss in “The Cosmic Chiasmus”). In his Whole Counsel of God podcast, Fr. Stephen De Young recently commented on the strangeness of the chapter break (introduced in modern times) coming between the sixth and seventh days. Yes, numerically that is strange, but also structurally I find it not a little perceptive. The aspect of the sabbath here that portends death — ultimately Christ’s resting in the tomb — is being utilized structurally as the center of a pentad, not as the heptatonic lead-in to an octave. Yes, the thematic suggestion is present, powerfully so, and the meaning of an octave is directly related to the sabbath sequence, but structurally this is not yet an example of the octave that I seek.

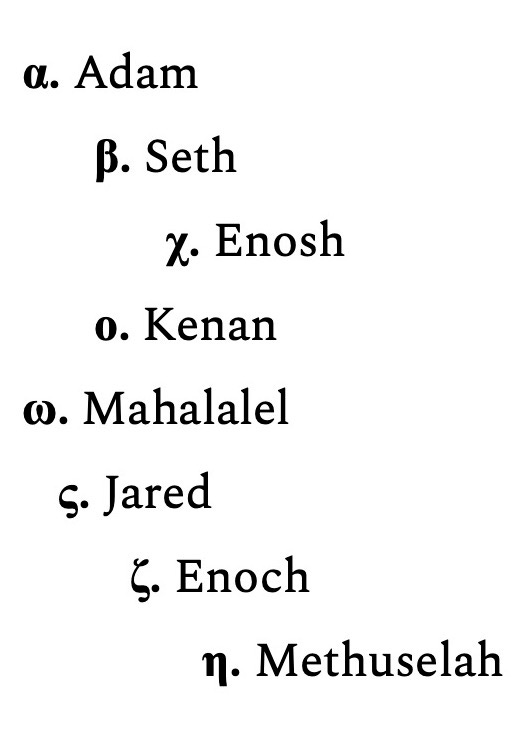

Could Enoch and Methuselah be a clue?

In the genealogy of Adam’s line through Seth in Genesis 5, the seventh generation, Enoch, conspicuously lives a measly 365 years, and then, because he walked with God, “was not, for God took him” (Gen. 5:24). This mysterious non-death is followed by his son Methuselah, the eighth generation of Adam and the longest living patriarch in the Bible at 969 years, beating his grandfather Jared (Enoch’s father) by seven years. As such, this Methuselah could represent symbolically the everlasting life of the age to come — the eighth day.

However, the genealogy isn’t eight generations long. It continues past Methuselah two more begettings, to Lamech and Noah, the ninth and tenth generations of Adam. Whereas Methuselah in the eight-spot seems in a limited way to symbolize the age to come, it’s really Noah in the ten-spot who crosses over into another world. The idea that this text comprises a decad is reinforced by Genesis 11 when the genealogy of Shem spans ten generations of Semites down to the sons of Terah: Abram, Nahor, and Haran. From Adam to Noah is ten generations, and from Shem to Abraham is ten generations. That’s the textual form of these pericopes.

But what is a decad, and can it be related to the octave? I frankly have not examined enough decadic literary structures to speak about them with any confidence. Honestly, I don’t see them all that much. (Neither the ten plagues on Egypt nor the Ten Commandments, for a couple of obvious examples, take the shape of a decadic literary structure.) And when looking at these genealogical decads, I’m relying heavily on etymology of the names in Hebrew — a language I haven’t studied as I should — according to different resources that don’t always agree with each other. Even if I had studied Hebrew, I still don’t suspect I’d have much to hang my hat on. Names like Lamech and Arpachshad aren’t even Hebrew, their derivation being lost to the ages. With all those caveats in hand, though, doesn’t this look like it could be an octave, a fivefold chiasmus followed by a triadic ascent?

Adam (α.) means “human”, the creature made in the image of God, and Mahalalel (ω.) — of the first generation of men to have the divine signifier “el” in their names (Mehujael in Cain’s line is also fifth from Adam) — means “praise of God” or “shining of God”. Chiastically central to that pair, Enosh (χ.) means man, but with the added sense of mortality, prefiguring the death of Christ. When he was born, “At that time began they to call upon the name of the Lord” (Gen. 4:26). In the intermediate positions, Seth (β.) means “appointed”, as when Israel is appointed to the service of God before the time of Christ, and Kenan (ο.) means “acquiring”, as when the Church acquires the grace of the virtues after Christ. I find these first five rather appealing as a sequence in the style of a cosmic chiasmus.

What remains to fulfill a potential octave is the 6–7–8 of the next three patriarchs. Methuselah in the eight-spot (η.), as mentioned, is the longest living human in a world where long life is considered a divine reward. Enoch in the sabbath-spot (ζ.) is relieved from the cycle of life and death on account of his virtue. And the name of Jared in the six-spot (ς.) means “to descend”, because according to the Book of Jubilees, “In his days the angels of the Lord, who were called Watchers, descended to the earth to teach the sons of men, and perform judgment and uprightness upon the earth.” According to the same source, he married a woman named Baraka, meaning a spiritual blessing, and she was the one who brought forth Enoch, who walked with God. Thus these three generations plausibly comprise a triadic progression of praxis, theoria, and mystagogy. I’d call it an octave if the sequence ended there.

Lamech (θ.) and Noah (ι.), however, follow as the ninth and tenth generations, and that right there is the first time I’ve ever used the Greek numerals theta (nine) and iota (ten) as symbols. What to make of the decad? I speak not just of the number ten, the symbolism of which is as well attested to as any other number. I speak of the decadic sequence. Is it possible it could be built on the octave the way the octave builds on the pentad? The eighth day is the day with no evening, indicating something everlasting that circumscribes all sequences. How could it be limited within a sequence?

My only guess relates to how all items in the octave sequence have the potential for negation and perversion. In the place of the Lord’s day can step an anti-Lord’s day. The long years of Methuselah may seem to reflect eternal life, but in fact he dies the same year as the flood; he does not cross over into the next world. It may be that he died before the flood — maybe he was virtuous, and so God held back the flood until he passed. Or maybe he perished in the flood, having spent all his vast potential for repentance like everyone else not named Noah. We don’t know. This ambiguity reflects that of Christ and antichrist, the way human evil has been given power to usurp all Christian symbols. The nine (θ.) and the ten (ι.) then unpack that ambiguity, resolving it in the perfection of the ten, the perfection of Noah who does indeed traverse the end of the world, and with his progeny intact.

Before it, however, is needed an interval of metanoia and renewal, another type of sabbath. Lamech is a name of unknown derivation, but the son of Methuselah carrying this name in the Sethite line, who lived to the age of 777, shares it conspicuously with the descendant of Cain seventh in line after Adam, the founder of polygamy who murdered twice over and declared he shall be avenged seventy-sevenfold (see Gen. 4:19–24). Methuselah was of the same generation, the eighth from Adam, as the sons of the first Lamech, descendant of Cain. That’s where the description of Cain’s line ends; if the sons of Cain carried Adam’s seed to a ninth generation, the flood made them not worth mentioning. Methuselah, on the other hand, carried his line on to the ninth generation with a new Lamech, he who was a new sabbath rest and the father of Noah, a true eighth. Maybe the tenth is like a true eighth, and the triadic sequence of η.–θ.–ι. (8–9–10) is contained within the inherent ambiguity of the octave.

Perhaps. I can’t say I’ve verified this pattern elsewhere. The first place I’d want to look is the tenfold genealogy of Shem through Abram and his brothers in Genesis 11, but when I do, the results are inconclusive. Shem, whose name means “name”, as in reputation, is a good analogue for Adam the image of God. And Abram, the one who hears the call to leave the land of the Chaldeans for the land of Canaan, who receives the covenant of circumcision, and whose name means “exalted father”, is an excellent analogue for Noah. In between, however, the etymology of names is less helpful, as are also the scant biblical narratives. Possibly this decadic sequence is conformable to the genealogy of Adam to Noah, but I can’t say at this time.

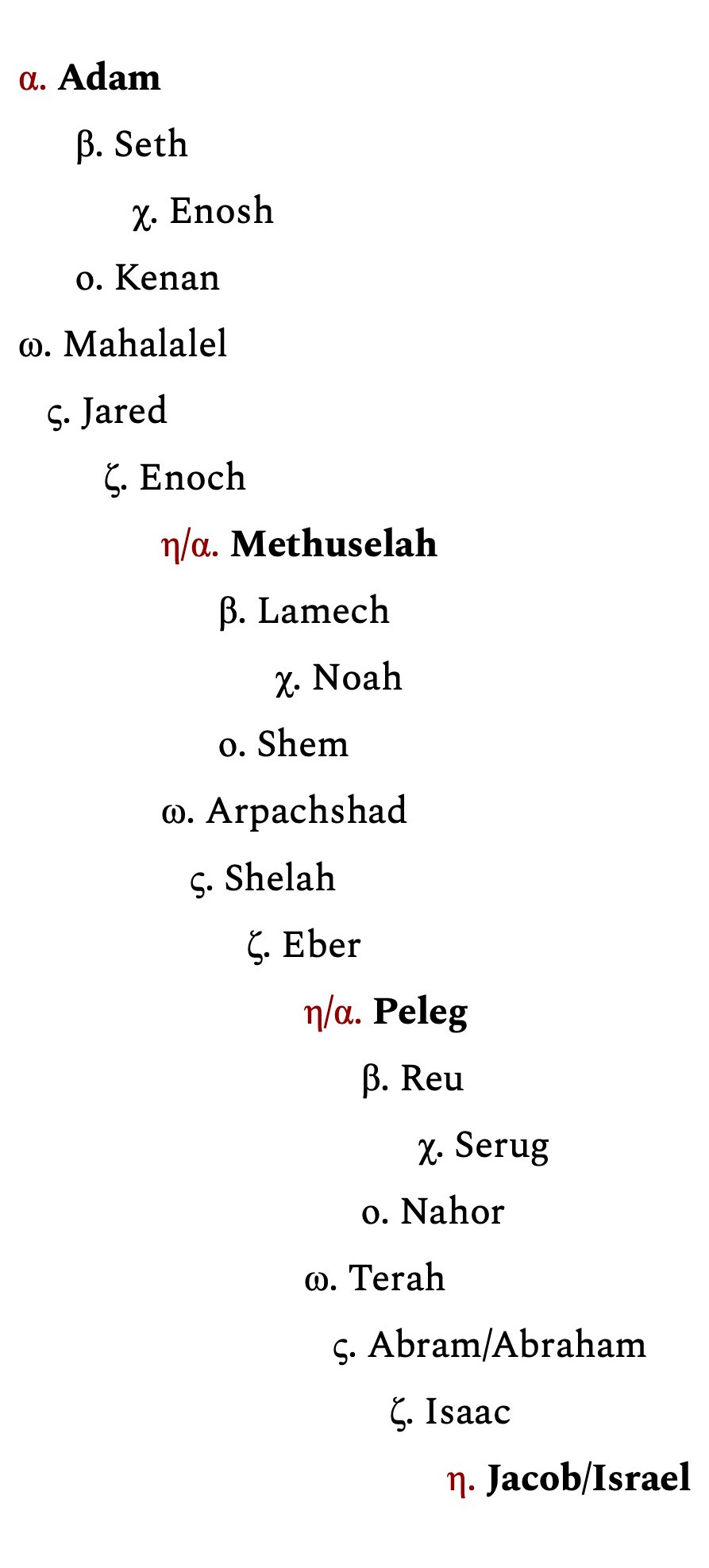

While I hesitate to apply a decadic interpretation to the line of Shem in Genesis 11, I am in fact much more bullish on a separate extra-textual contemplation. [This article is about to take a long, unexpected, roundabout journey; readers pressed for time, or losing interest, are invited to skip ahead to the concluding section if they like.] Aided a good deal by the Book of Jubilees, I see in this Semite sequence, joined with the preceding genealogy, the following triple octave shape including Isaac and Jacob:

From Adam to Israel is 22 generations, a three-octave structure with overlapping Sundays, as with three octaves’ worth of musical scales. The triadic structure is based around two separations, two global divisions. The second octave overcomes the nephilim-induced deluvian catastrophe, and the third octave undergoes the division of nations at the Tower of Babel. Of the patriarch Peleg (η/α.) it is said that in his days “the earth was divided” (Gen. 10:25), and the Book of Jubilees says furthermore that the birth of his son Reu (β.) coincided with the beginning of the Tower of Babel’s construction. Peleg was thus also the first generation of the Hebrew people, a new designation for a post-Babel world, the ethnonym Hebrew being derived from Peleg’s father Eber (ζ.), which means “crossing over”.

Serug (χ.), meanwhile, a name that means “branch” (as of a tree; it’s related to the word for tendril or twig), would be the first generation coming of age in this divided world. The Book of Jubilees describes his birth as coinciding with the instigation of war and bloodshed and slavery and idolatry. He shamefully took up this idolatry and had his son Nahor (ο.) educated in the Chaldean ways of divination and astrology (a negative fulfillment of the omicron-typology). The life of Nahor’s son Terah (ω.), meanwhile, was marked by a plague of crows eating everyone’s crops, causing a catastrophic famine. This lasted until the time that his virtuous son Abram (ς.), who resisted pagan worship, managed to fend off the crows in an act of determined purification. All of these additional narratives are from the Book of Jubilees. Then Isaac (ζ.) could be seen to represent illumination by means of the Christological revelation occurring at his sacrifice — as well as anti-illumination in his late-age blindness both physical and metaphorical, in that he preferred the wrong son among his twins. Jacob (η.), the right twin, represents perfection in his renaming as Israel and fathering of the twelve nations to be covenanted with God.

Going back to the second octave in this triad, I can say I like the sequence of Methuselah–Lamech–Noah as parallel to Peleg–Reu–Serug in the α.–β.–χ. positions. Those generations relate in the same way to the global challenges of their days, howbeit Serug appears to have succumbed where Noah (χ.) succeeded... though I suppose Noah’s drunkenness did accomplish something similar to Serug. Anyways, Shem (ο.) fits the four-spot as having benefited from his father’s sacrifice and living a virtuous life, filling the earth with his seed. His son Arpachshad (ω.), meanwhile, according to the Book of Jubilees, received the allotment of southern Mesopotamia known as Chaldea, a geography suggestive to me of the judgment due to the separation of the rivers and its subsequent identity as the location of Babylonian exile. Shelah (ς.) and Eber (ζ.) are absent from the Book of Jubilees, so all I have to go on is the etymology of their names, “sent” and “crossing over”, respectively — the latter of which is excellent for the sabbath-position because it denotes change. “Sent” suffices for the stigma-position betokening purification; the word shelah can also mean javelin or dart or some other weapon that is projected or “sent”. Thus is the purified soul sent out of sin, or as a weapon against sin. Peleg (η/α.), again, is the one in whose time the earth was divided into the nations, the oneness of humanity being decimated according to the negative mode, or, if viewed positively, fulfilling the divine mandate of multiplication, of fructification. The name Peleg means division, but in a way that is also used for a brook or small river.

If the genealogy of Shem through Abram in Genesis 11 were to form a decad after the genealogy of Adam through Noah, the symbolic associations with the patriarchs would all be shifted around, restarting with Shem, and they make less sense to me in those positions. This procession of weeks appears to fit the generations better — and perhaps, enticingly, it illumines an ancient prophecy from the Epistle of Enoch in 1 Enoch, the so-called “Apocalypse of Weeks”.

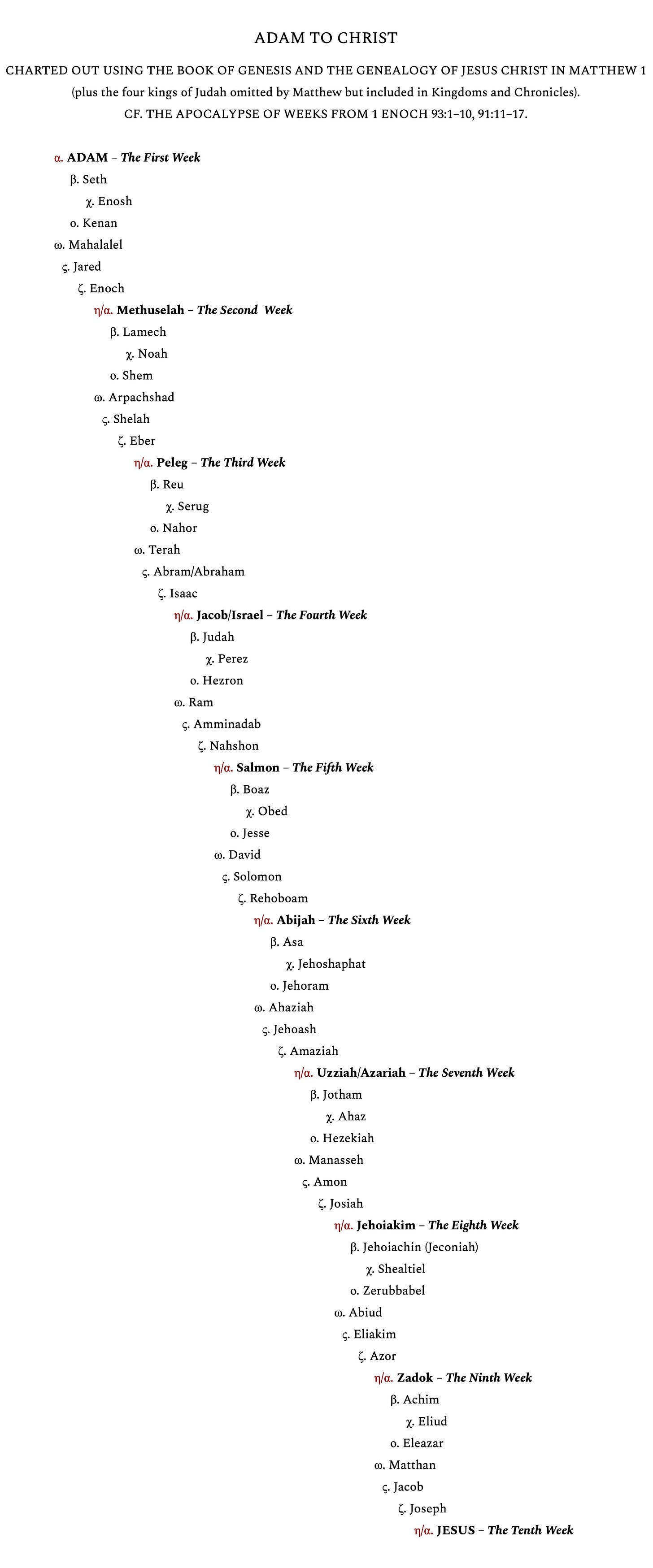

After all, why stop counting the generations with Jacob/Israel? If you keep running with the genealogy past the Book of Genesis and the birth of Perez to Judah and Tamar described there, you’ll find the line of Perez to David at the end of the Book of Ruth, plus the line of Davidic kingship in Kingdoms and Chronicles, and then the rest of the line down to Joseph the Betrothed, legal father to Jesus our Lord, in the first chapter of Matthew. I haven’t gone through the symbolism of each and every figure on this list, but what I have reviewed looks promising; and just look at how well the numbers work out:

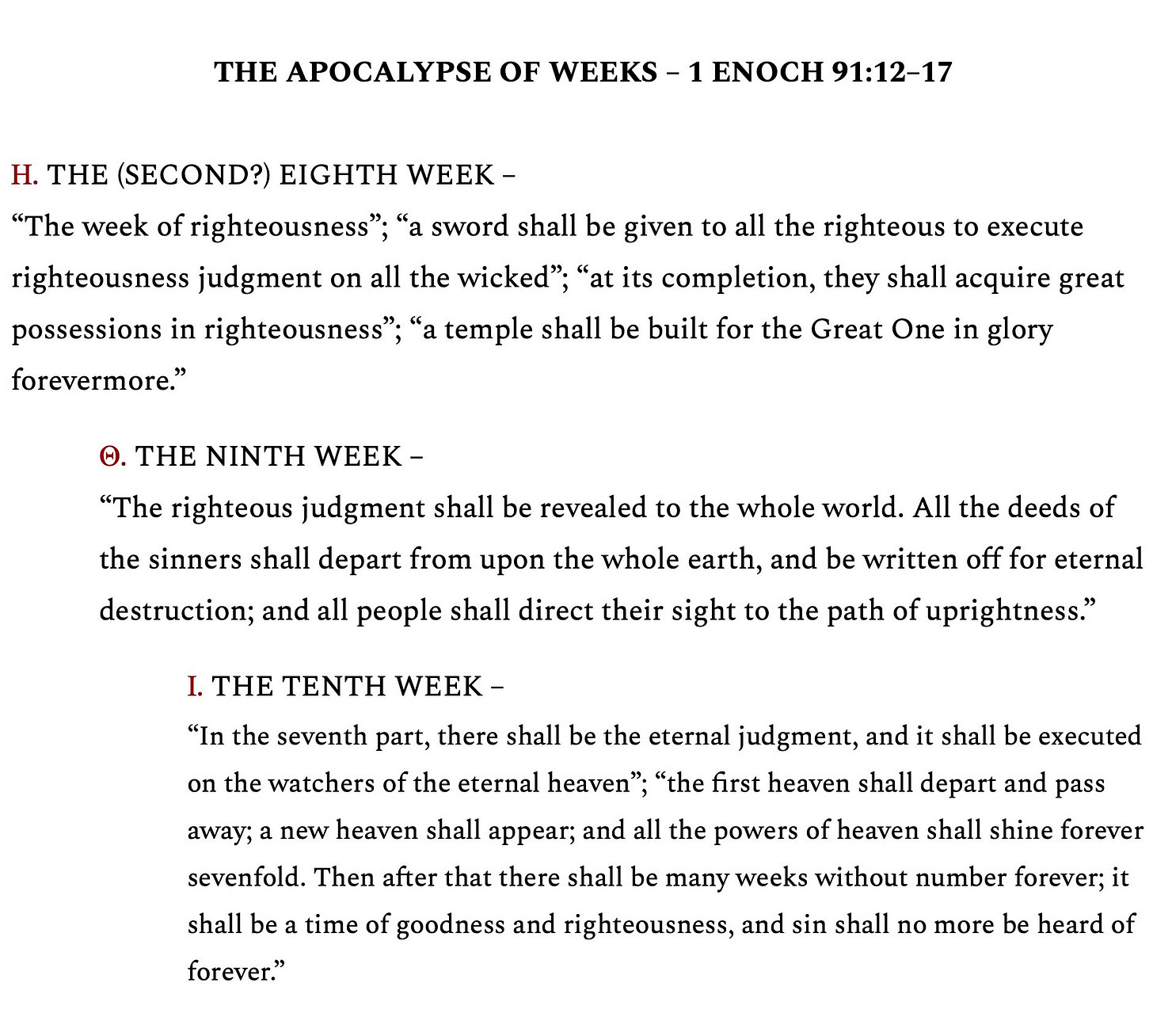

In the Apocalypse of Weeks, meanwhile, in 1 Enoch 93:1–10 and 91:11–17, Enoch identifies himself as having been “born seventh in the first week” (93:3). He goes on to describe a second through a seventh week and then, in a passage of ambiguous textual placement, an eighth, ninth, and tenth week. If a week is to be understood like a heptatonic sequence, not necessarily of days, but possibly, according to how Enoch identifies himself, of generations, then this list above could potentially represent the fulfillment of this prophecy. The Evangelist Matthew explicitly calls attention to there being fourteen generations from Abraham to David, fourteen generations from David to the Babylonian exile, and fourteen generations from the Babylonian exile to Christ (Matt. 1:17). If we understand Abraham to be at the end of the third week of generations, Matthew is deliberately adding six more weeks, making the messianic subject of his Gospel the beginning of the tenth week, which 1 Enoch describes in unequivocally eschatological terms.

As for the rest of this sequence of generational cycles that I’ve plotted out, it nearly works out according to how 1 Enoch describes the weeks. Nearly. The first five weeks, for one thing, are a cozy fit:

As you read 1 Enoch’s description of the sixth week with my genealogy in mind, you should be hearing a loud record scratch: there’s a major discrepancy there. First of all, the sixth octave of generations is in fact a time of straying from wisdom, and that is when “the man ascends”, a prophecy everyone agrees is about Elijah — the last biblical figure to be referenced directly. But... 1 Enoch goes on to say the temple will be burnt and the exile will begin already at the end of the sixth week. In the order of the genealogy I’ve drawn up, that doesn’t happen until the end of the seventh week (the final vassal king of Judah at the time of the destruction of the temple was Zedekiah, a son of Josiah like Jehoiakim). That’s a conspicuous deviation between the two models. As long as 1 Enoch was alluding to historical figures, it tracked with the generational octaves. Henceforward it becomes harder to square the connections.

Thus 1 Enoch says for the seventh week, “An apostate generation shall rise” and “all its deeds shall be perverse,” which doesn’t sound all that different from the hearts of all straying from wisdom in the sixth week. But that naturally fits the genealogical version of the seventh week in that the apostasy that culminates in exile and the destruction of Jerusalem was ongoing at that time. What it goes on to say about the elect ones of righteousness from the eternal plant of righteousness (earlier identified as Israel), and how sevenfold wisdom shall be given them, ... I guess could sound like the flourishing of prophets and rediscovery of the Law at the time of Josiah. But honestly it sounds to me more like the post-exilic restitution of Judah to Judea and Ezra’s biblical revival, which occurs during the eighth week of generations, not the seventh.

In the surviving manuscripts of 1 Enoch, a description of any further weeks does not follow from there in the 93rd chapter. Rather, back in the 91st chapter, there is a description of an eighth, ninth, and tenth week that many assume is misplaced and continues the Apocalypse of Weeks. Some editors indeed choose to move these verses to reflect that textual interpretation. I lack complete confidence in that decision, however. Judging by the prophetic content, I don’t see unambiguous continuity. Nor am I ready to dismiss the scribes who produced the manuscripts as incompetent. There’s something strange going on here in the textual tradition that I’m not sure we fully understand.

It begins in the 91st chapter with the mention of an eighth week, but the original Ge‘ez translation (the only surviving version in full) doesn’t just say “eighth week”. Now, I don’t know the first thing about Ge‘ez (besides, that is, which way the apostrophe should point) and am just going by what different explanations say. But one possible translation says, intriguingly, “the second eighth week”. It possibly could be understood as “another eighth week” or “another week, the eighth”. This is not consistent with the sequence of seven weeks prophesied in chapter 93, but neither is there any context in chapter 91 that makes sense of it, a chapter which up until this point had not been talking about weeks — though what it had been talking about is not out of line with the prophetic content of the “second eighth week”. Let’s look at the prophetic content:

If these descriptions — both greater in length and lighter in historical detail than previous weeks — were to match with the genealogical octaves, the righteous judgment on all the wicked in the eighth week would have to be understood typologically at best, and the temple for the Great One would have to be the Second Temple. Its “forevermore” status, again, would have to be understood typologically, not historically. As for the ninth week... it’s admittedly hard to square this description with the theta-symbolism I named when attempting to understand the decad. And you’d have to squint pretty hard to see this as a description of the era known for Hellenistic, and ultimately Roman, domination of Judea. Even if you could force an inference of typological connection, why in the world would a prophet think to describe that era in this way? What would be the purpose in that? I don’t see any. The tenth week, meanwhile, is a clear description of the final judgment, which is said to begin on the seventh part of the tenth week. The generation of Jesus Christ is indeed the omega of all things, even as it is the alpha. As my genealogical chart has it, though, Jesus — in Whom the final judgment exists eschatologically — is the very beginning of the tenth week, suggesting that all perfection is reached immediately, not after a sabbath’s wait. So that’s a little weird.

I wish this decad of weeks in 1 Enoch could give me insight into the pattern of the decadic sequence, but I’m not even confident that the last three weeks formally belong with the first seven. In his book Apocrypha: An Introduction to Extra-Biblical Literature, Fr. Stephen De Young describes the eighth, ninth, and tenth weeks in 1 Enoch 91 as messianic, ecclesial, and eschatological (respectively), which makes a good deal of sense, no squinting necessary. But that prophetic pattern is definitely Χ.–Ο.–Ω., as in a cosmic chiasmus. To my pattern-reading eyes, that doesn’t fit neatly with the heptatonic sequence before it. It might work if you understood the messianic eighth week as the second eighth week — that is, the tenth week. And then the Ι–week would double as the Χ–week (Ι and Χ are, it just so happens, the Greek initials for Jesus Christ), and it would be natural for an omicron and an omega to follow. But in that case, whither the eighth (the first eighth) and ninth weeks? The intertestamental period is obscure enough without intertestamental literature itself overlooking it!

My formalistic interpretation of the Apocalypse of Weeks — at points so promising — doesn’t hold together in the end. St. Maximus teaches that the point of failed conjectures is to obtain humility from them, and I thank God for that. In all sincerity: Alleluia. Formalistic interpretation, we should always keep in mind, is a method and a tool, and not an end in itself.

Returning to my original quest, I can declare this contemplation of generations only to have been an enriching detour. I can see the meaning of the octave all over these passages in Genesis, but the concrete literary text therein cannot be accounted for by means of the octave structure alone. I have no other candidates in Genesis and proceed to the second Book of Moses, where I already know I’ll succeed in my search.

The Theophany at Sinai

Nearing fifty days from Passover, fugitive Israel arrives at the base of Mt. Sinai in the Book of Exodus, ch. 19. As yet the Torah — the Scripture I have been searching — has not been given to them, but now it will be. At first there is an introduction between Israel and their God, and immediately they are taught the boundaries of their intercourse. The people are warned to keep their distance and are given three days to cleanse themselves in preparation for God’s descent upon the mountain. These instructions have been delivered to the prophet Moses, who alone is made worthy to approach God. The third day comes, the Lord descends and convenes with His prophet, and Moses is sent to the people.

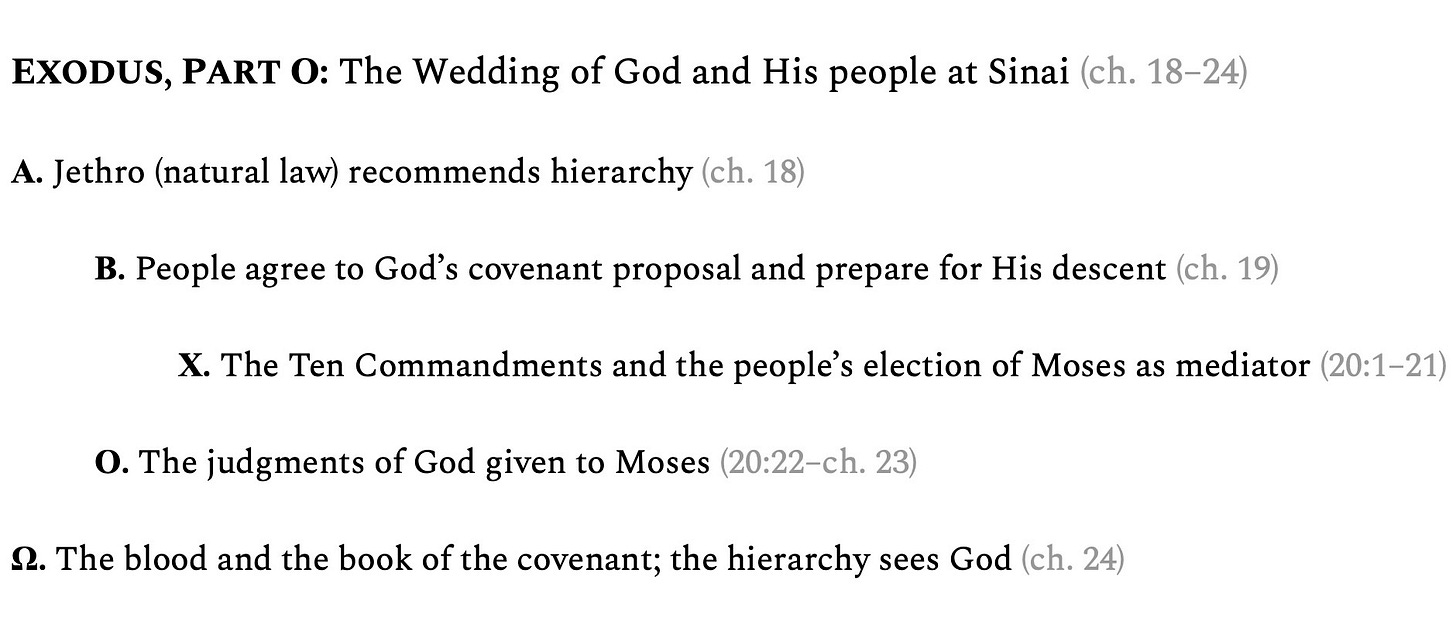

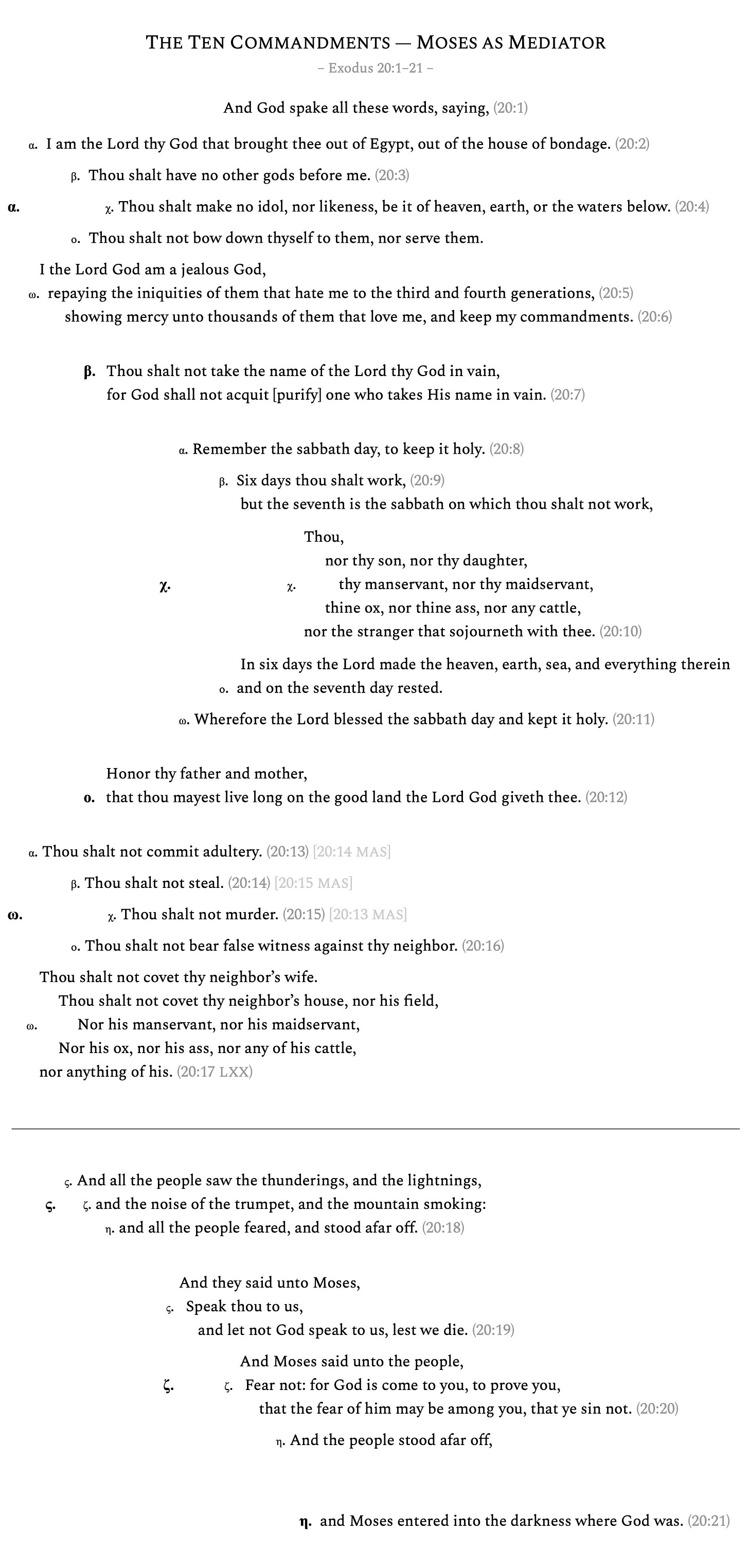

What follows immediately in the text, in ch. 20, is what is later in Exodus identified as the Ten Commandments (see 34:28). The whole of ch. 19 forms a neat cosmic chiasmus (see outlines on my website), and a set of additional laws commences in 20:22 and continues through the end of ch. 23. That leaves 20:1–21 as a single passage, the chiastic centerpiece of the fourth act of Exodus.

The thing is the Ten Commandments form a beautiful pentadic structure in just the verses 1 through 17, as I explain in “The Cosmic Chiasmus.” That leaves verses 18 through 21 dangling there as something extra. I believe that the fearful election of Moses as mediator by the people of Israel, narrated in those verses, belongs in the center of Exodus Part Ο along with the Ten Commandments, and that together they form an octave structure, the earliest in the Torah that I can identify.

First (ς.) they feel the fear, then in humility (ζ.) they are given to transcend the fear by understanding its purpose, that they sin not — then (η.) their mediator, the best among them, undergoes a divinizing embrace, that which is relatively called darkness because it lies beyond understanding. This fractal pattern of ς.–ζ.–η. is visible, furthermore, within the stigma- and zeta-parts. In verse 18, that the people feared and stood afar off is the perfection of their praxis. Once they enunciate their humility and the purpose of their fear is revealed to them in verses 19 and 20, the stigma and zeta of the zeta, then it says again that the people stood afar off, but not also that they feared. The perfection of their illumination lies both in their fulfilling and in their transcending the fear on which their praxis is based. Then in the end, the perfection of their three stages of perfection comes in the form of entry into divine darkness.

When God names Himself “the Lord thy God” at the beginning of this octave, claiming Israel as His people for having rescued them from bondage and prohibiting their worship of other gods or any false incarnations, the finale of this octave was always the end He had in mind, an incarnation only He could achieve: the loving inclusion of created human nature within the life of His divine nature beyond the light of this world. The purpose of the Ten Commandments — this stable, unchanging pentadic expression of human life in righteousness — is for their whole structure to be subsumed by this triadic transformation (ς.) based in fear, (ζ.) elevated by knowledge, and (η.) perfected in love.

The octave structure is both so immensely satisfying and so immensely moving. What do we want from love? We want to have revealed what and who we are, and we want that to remain while at the same time we become something that we’re not. Without loss of a stable identity, we want a life that is eternally new, eternally other. By harmonically combining both stability and change, the octave provides the most fulfilling image of the cosmos energized by God. The octave note is continuous in identity with the root; it is one tonic. Yet at the same time it is elevated to a different plane as a new note. Music naturally happens this way. Time, the sequence of days, is naturally created this way.

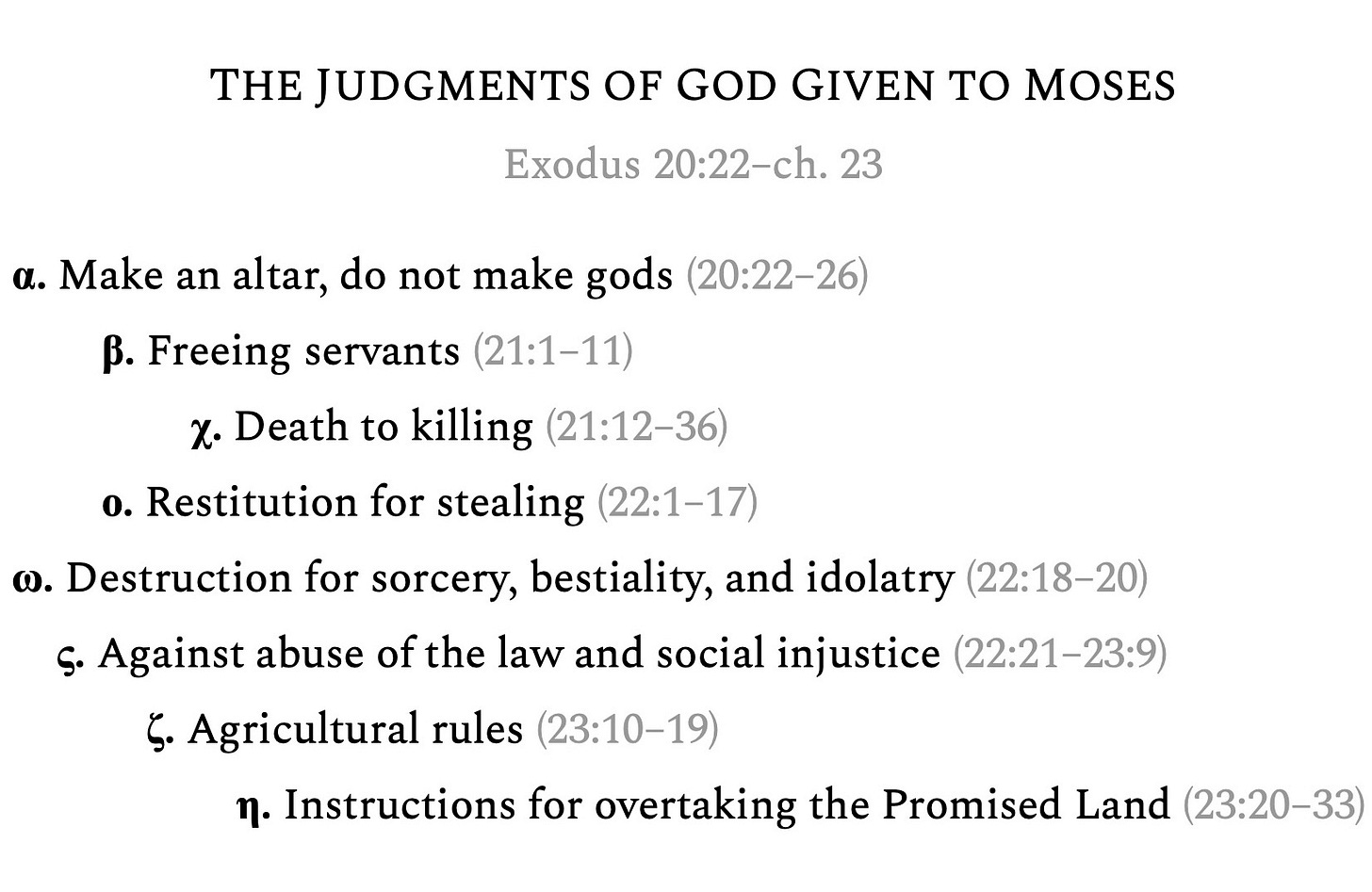

And sometimes the Bible is written this way. After the Ten Commandments and Moses’s ascent into divine darkness, Scripture wastes no time in playing its second octave. I see no better way to organize the judgments of God given to Moses in Exodus 20:22–ch. 23 than in octave form.

I’d talk more about this structure, but I’ve already fulfilled my assignment to name the earliest octave. And from the Hexaemeron, to Enoch and Methuselah, to the Ten Commandments and the divine darkness, I’ve also completed the three-part ς–ζ–η structure of the post. There’ll be no nine or ten here!

With each post it is becoming progressively harder to read a Psalm without awakening to the brilliance of these structures silently hiding within!

“Oh, the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are His judgments and His ways past finding out!” Romans 11:33