In the following video posted a couple months ago, we are presented with the following, not insignificant exchange:

Jordan Peterson: Well, Ben Shapiro told me that the original Hebrew for what’s translated as ‘help meet’ in the King James Version is actually something like ‘beneficial adversary’.

Matthieu Pageau: It’s because it says God created a ‘help against him’ — that’s literally what it says, a ‘help against him’.1

I’m sure no authority on such matters, but insofar as I’ve got a Substack newsletter and a column to write this week, I gotta say: This interpretation of ezer kenegdo is wrong. The insertion of a dialectical opposition between man and woman in Genesis 2 is not warranted at all.

The relevant phrase occurs in Genesis 2:18 and again in 2:20. It concerns God’s inspiration for creating woman, and the KJV translates it as ‘an help meet for him’ — that’s ‘meet’ as in ‘appropriate’ or ‘fitting’, an archaic word for most, though it’s commonplace in the church hymnography I’m used to; anyways the RSV updates it as ‘a helper fit for him’. The word for ‘help’ or ‘helper’ (ezer in Hebrew, boethos in Greek) doesn’t imply an inferior assistant necessarily. It just means one who helps; God Himself is often called this word relative to man. It’s not going to be the focus of what I’m writing here.

Kenegdo (כנגדו), on the other hand, the word translated as ‘meet’ or ‘fit’ — or ‘against’ — is the operative word in the interpretation I’m rejecting. It is a unique variation on a common word in Hebrew. Its components are a pronoun suffix (the letter vav, which here transliterates as ‘-o’) that in context refers back to Adam; a prefix (the letter kaf, here responsible for the ‘ke-’) that means roughly ‘like,’ ‘as,’ or ‘similar to’; and, centrally, the preposition neged which is wrongly having a sense of opposition being read into it.

If we look at other uses of neged in the Pentateuch, we can see it usually means ‘before’ in the spatial sense of that word, as in ‘in front of’ or ‘in the presence of’. A typical example is Exodus 19:2, where it says the people of Israel came to the desert of Sinai and there “camped before the mountain.” That’s as if to say they were ‘in the presence of’ or ‘in view of’ the mountain. In Genesis 33:12, when Jacob and Esau have their peaceful reunion, Esau tells his brother, “Let us take our journey, and let us go, and I will go before you” — ‘before’ as in ‘in front of’. In Numbers 25:4, on account of idolatry with the daughters of Moab, Moses commands that the chiefs of the people be hanged “in the sun”, as in ‘in the presence of’ or ‘in full view of’ the sun.

That’s a decent enough sampling of neged and its uses, but a better appreciation of the word can be had by looking at its root verb nagad. This word has the sense of ‘declare’, ‘show’, ‘manifest’, ‘announce’; it’s often just translated as ‘tell’. Technically it means something like ‘to place in front of’ or ‘to make conspicuous’. God asked Adam, “Who told you you were naked?” (Gen. 3:11); likewise Ham saw the nakedness of his father and “told his brothers outside” (Gen. 9:22). Pharaoh asked Abram, “Why didn’t you tell me she was your wife?” (Gen. 12:18). When young Joseph dreamed a dream, he “told his brothers” (Gen. 37:5). When Pharaoh related a dream to his magicians, “none could declare it to [him]”, but Joseph explained that in the dream, God “showed to Pharaoh what he is about to do” (Gen. 41:24–25). This is just a sampling from Genesis; in the final drama between Joseph and his brothers in Egypt, there’s lots of ‘telling’ going on in both directions, all using the verb nagad.

That’s enough for now; nagad’s a pretty common word. A lot of these connotations are pertinent to what Matthieu Pageau goes on to say about man and woman in a positive sense. But there’s no cause to see an adversarial relationship built into the principal structure of a gendered humanity. Kenegdo, based on the preposition neged, does not mean opposite. Sure, because neged means ‘before’ or ‘in front of’, it’s sometimes thought of as ‘opposite’, as in ‘facing’. Even in English the word ‘opposite’ is occasionally used in a dialectically neutral way that implies no negative contrast or antagonism. Maybe the Israelites could be said to have camped ‘opposite’ Mount Sinai. That is not at all to open a door into a dialectical contemplation of the text.

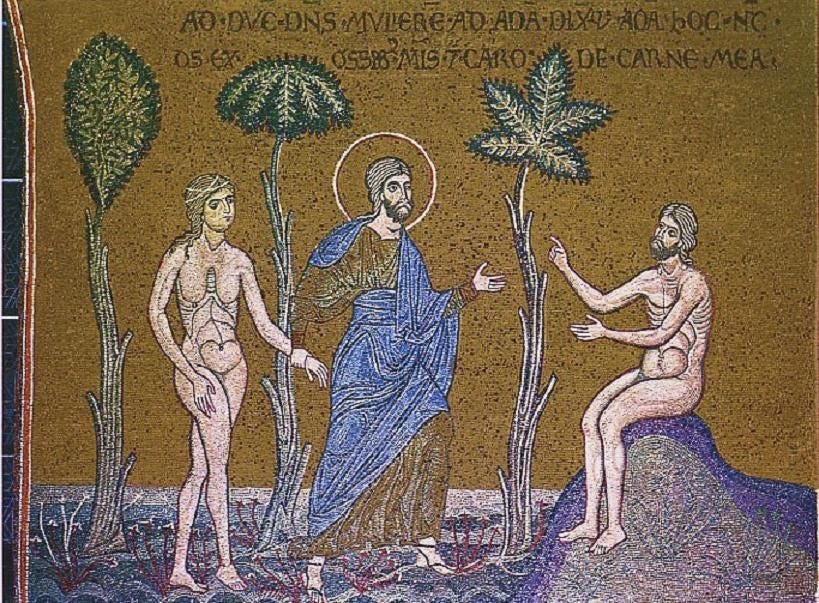

The ancient Septuagint translation of Genesis into Greek grounds us in a view of how a collection of Hebrew-literate minds understood the phrase a couple centuries before Christ. We even helpfully get two variations on what kenegdo means since it is translated differently the two times it appears. In 2:18 it’s kat’ auton, and in 2:20 it’s homoios auto. The first one means ‘according to him’ or ‘corresponding to him’, whereas the second means ‘similar to him’.2 Both meanings are contained in kenegdo, as, recall, the prefix ke- brings shades of ‘similar to’ or ‘like’. The woman, then, is someone who stands in the man’s presence and is similar to him. This differentiation gives great help to him. As the contextual narrative makes clear, she ‘corresponds’ to him in a way that the animals fail to do.

Whence the adversarial understanding? And why is this important? We need to reject the idea that the principle of the sexual differentiation of anthropos into man and woman can at all be contemplated according to the patterns of dialectical thinking. This is important because dialectic — the interplay of negation and opposition — denotes polarization, and that’s precisely what happens after the fall when human nature is corrupted.

Genesis 3:16 features God’s knowing response to woman’s fall from obedience, and He in part says to her, “Your desire shall be to your husband, and he shall rule over you.” Longtime readers of my month-old newsletter may recognize in this dynamic of longing and lording the pattern of the passions epithymia and thymos. As I began to say in “Are you filled with anger? Are you filled with lust?”, this appetite and this drive work in polarized opposition to each other like a magnet. They work to tear us apart while at the same time preventing us from escaping ourselves. That’s because, like a magnet, the poles are contained within each other; polarization exists on a molecular level. Man and woman each have epithymia and thymos working inside of them even as they typically personify one to the other. This is the pattern of corruption and death. It is the sentence we bring down upon ourselves when we sin. It’s ‘Babylonian exile’, as Babylon is the land split between the two rivers it contains.

Dialectical reasoning works the same way, according to patterns of opposition and negation. When a thing is defined by negating its opposite, it tragically then depends on what it has negated for its very meaning. Dialectic is death, and though the world was created capable of death (as a means of limiting the effects of any potential sin), it was not intended for this purpose. The world was created in life, centered on the tree of life, and if we are to understand the principles of creation — if our minds are to rise from the dead and enter life — we must lay aside the patterns of dialectical reasoning so as to see things defined in relationship with each other, not in opposition. Symbolic thinking serves this purpose. Analogical hierarchies of meaning are how creation works. If sexual differentiation is at all to be a ‘help’ to us as it was designed to be even in a prelapsarian context, we must learn these symbolic patterns in a manner free of the dialectical corruption consonant with death and sin.

And just in case, in order to ward off any puritanical understanding of what I’ve just said, I do not mean that to think dialectically is to sin. Death is the consequence of sin and so is shaped like it, but Christ shows us it is possible to undertake the consequence of sin without having sinned. Love for sinners actually inspires such behavior. Dialectical thinking may only be appropriate for tracing the patterns of corruption, but that can be an essential component to repentance and confession, to “dying daily”. Christ engaged dialecticians in argument plenty in the Gospel, but always with an eye to transforming the conversation.

Take for instance the time Pharisees and Herodians cooperating with each other approached Christ to snare him in the same dialectical trap to which they were subject (see Matt. 12:15–22; Mark 12:13–17; Luke 20:20–26). They asked if it were lawful to pay tribute to Caesar. If he said yes, the Pharisees could accuse him, and if he said no, the Herodians could accuse him. How he responded broke their lines of reasoning like the gates of hades to which they correspond. He asked to be shown a denarius with which the tribute is paid and then said, “Who’s head is this and whose title?” They responded from their dimwitted perspective, “Caesar’s,” but the answer is not actually so simple. For to whom does Caesar’s head and title belong? Man is made in God’s image, and all earthly authority is a symbol of God’s authority. In order to understand these things, you have to think analogically — not dialectically.

It’s the same thing as man and woman. In Protestant society, there is big debate over the meaning of ezer kenegdo and other Scriptural passages addressing gender relations. Complementarianism upholds a hierarchy while saying men and women are hierarchical complements of each other, whereas egalitarianism avers complete equality of the sexes, decrying all hierarchical modes. The debate is shaped by the same dialectical pattern of thinking to which the West has been sold for the past thousand years. It insidiously polarizes every issue to ensure that everyone is wrong about everything all the time.

The proper Christian, symbolical view can acknowledge the existence of hierarchical patterns while recognizing the purpose of the hierarchy is its own anagogical collapse upwards in theosis. Christian hierarchy does not work like worldly hierarchy. The first shall be last, and the last shall be first. The Virgin Mary, occupying the lowest part of society and of creation, is revealed in the cave of the manger to be the Mother of God, more honorable than the cherubim and beyond compare more glorious than the seraphim. Christ God calls His disciples friends. How does that make sense? It’s incomprehensible but true. The divinizing dynamic between high and low otherwise known as love, which both differentiates and equalizes, cannot be captured by dialectical thought processes. The proper understanding of spiritual truths is scattered and expelled by submission to dialectical logic.

Dialectic is death — we may be called to endure it like Christ, but like Christ we are to do so with the power of life that overcomes death.

Jordan B Peterson, “The Language of Creation | Matthieu Pageau | #292,” YouTube, September 29, 2022, at 26:02.

For English translations of the Septuagint, Brenton has “a help suitable to him” (with “according to him” as an alternate reading) and “a help like him”, while the NETS has “a helper corresponding to him” and “a helper like him”.

Thank you Cormac. Very helpful and in depth. I think that a dialectical approach is a natural consequence of not rooting thinking in Trinitarian theology. Within the Trinity, one of the divine Hypostasis (Persons) cannot be described in terms of not being like one of the others, since there are two hypostases not like the other. The divine Persons can therefore only be described relationally, by the nature of their relationship with the other two. This means that characteristics and 'roles' of any one created reality (be it male, female, earth, heaven or whatever) cannot be understood in terms of opposition to another i.e. dialectically, but only by love and relation. So, for example, love for one other human person can only operate in a healthy way if it includes a third 'party' (ultimately God, but also one's neighbour). Aidan Hart

Do you have any thoughts on the relationship or anagogical complementarity between marriage and monasticism in this light? It seems in some places to be presented dialectically, but while the Church confesses virginity the higher mode, it also steadfastly retains the doctrine of the holiness of marriage, and the synergy and common telos of both paths. Any deeper insights? Forgive me if I am unclear or misrepresent the teaching of the Church.