Barbie’s call to monasticism

What I think most people are missing about the blockbuster movie

I hadn’t planned on seeing Barbie in a theater. It’ll be streaming in just a few months, and nobody’s exactly pressing me to join the conversation. Getting to a movie theater and spending the time there has turned into something of a sacrifice for me. It really is a religious practice. Generally I’d rather spend those opportunities going to actual Church. But I was interested in seeing Barbie. I liked Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Little Women a whole lot and wanted to see her follow-up. The doll and the brand do not interest me, but if it interests Gerwig this much, I’d hear her out. Also, I was interested in the conversation. It’s an interesting conversation.

Enter a day’s worth of car maintenance in a town with a theater, at a dealership with shuttle service, and behold, I have seen Barbie. Barbie is a movie with a vicious gender dialectic in it. Booby traps abound for anyone who can’t overcome the dialectic. The movie itself, however, is not unaware of the traps and in the end proffers a route for evading them. A lot of the critics of the movie that I’ve seen aren’t engaging with this aspect; mostly they’re falling for the dialectical booby traps and gender wars. Some critics in response mark the parity of satire that does exist in the movie, and they come off looking a lot better. But even still, Greta Gerwig is smarter than every critic of Barbie that I’ve yet encountered. Paul VanderKlay, give him credit, is smart enough not to play the role of reactionary man‑shriek, and makes good points, but if you’re not coming from a tradition that gives proper place to monasticism, I don’t think you’re going to be able to see clearly what Gerwig is reaching for, albeit in a humanist mode.

The movie isn’t flawless, no doubt, even relative to its own humanism. Let me add my voice to the universal chorus proclaiming how poorly written the corporate antagonists are, for example. But most of the flaws being talked about aren’t worth prioritizing. Here’s what I see as most pressing.

I. Beyond gender

I’ve seen in several places people refer to Ken as the real protagonist. He’s not. He has an arc, for sure, but it begins and ends purposefully within Barbie’s larger arc, being contained wholly therein. People have said the movie has too many endings. Again, sucked into the antagonism of it all, people are mistaking the dialectical gender conflict as the conflict of the movie. It’s not. Ultimately the movie is concerned with the conflict we have with gender conflict itself. By the time the “patriarchy” is subdued and “feminism” is restored in the ideological space of Barbie’s plastic fantasy land (and nowhere else, it’s worth mentioning, because neither idea does much to explain reality), this resolution — pilloried by certain critics — is recognized by the movie itself as unsatisfying. That’s why that’s not the ending. The dialectic of conflict and resolution up to that point is a chimera relative to any actual catharsis. That’s why Barbie herself, the heroine of the movie, has to make like Frodo and leave her world behind.

By the time Barbie-inventor Ruth Handler, played by Rhea Perlman, tells her creation that the world is a messed up place and that’s why we create things like patriarchy and Barbieland, in order to cope, it should be obvious to anyone paying attention that a dialectical equation is being made between patriarchy and feminist anti-patriarchy. To invert a pattern you identify as bad is just to generate a bad pattern. The movie itself is saying this in regard to gender.

And so reactionary critics counter with the marriage card, saying we need marriage to solve this problem (see Douthat and Crawford). That’s not a bad card generally, but I don’t think it’s the right play here. It’s not as if the movie would have been concluded better if Barbie submitted to marriage with a Ken doll whose original purpose (his logos) is to be her accessory. Ken worships Barbie like a mother goddess and looks to her to provide him meaning. That’s just not good husband material. In the end, appropriately enough, Barbie admits to her character design, that she is just not interested in Ken that way.1 Indeed it would have been a perversion of original purpose otherwise. I don’t think the screenwriters (Gerwig and filmmaker Noah Baumbach, who are unmarried decade-long partners with two children together) had any other choice in the matter. So Barbie the character and Barbie the movie, goaded by thoughts of death, reach for a mode of existence beyond marriage. This impulse of the soul, I would argue as a Christian, is perfectly good and right. Barbie is experiencing the call to monasticism.

II. Singlehood

The problem is this makes zero sense in a humanist context. Monasticism makes sense in pre-modern traditions where a principle higher than humanity is held in honor. Monastic dedication to that principle allows for a relationship of love that both transcends marriage and provides for marriage a pattern by which it can be meaningful beyond just being an engine for a pointless, endless cycle of birth and death. Barbie is reaching for such a principle and not unrighteously so, we must allow. When committed to humanism, however, would-be monastics unite themselves to no other principle than their own nature, composite of soul and body. The sick, materialistic solipsism that results creates a society of egotists and a famine of meaning. Those who would be monastics become “singles” instead, the etymological meaning of monastics, yet in this case passively prone to pleasure-seeking and pain-avoiding, with no defense against non-being’s threat to our existence. I’m sure many of today’s singles are meant for marriage instead, being confused by the humanist zeitgeist, but the real meaningful analogue to singlehood is monasticism. Those who would counter the resolution of Barbie with mere calls to marriage are missing the link upon which marriage’s meaning depends — they’re not escaping the toxic humanist context.

For by humanist context I refer not only to Progressive America but equally to the Protestant America that Progressive America identifies as bad and inverts (no more productive a maneuver when performed with religion than with gender). Protestant America’s nuclear family values do not on their own satisfy the human need for meaning, and nothing requires we resist Barbie’s calling attention to that. The movie, however, in reacting against that insufficiency, retains the humanist milieu in which Protestantism is embedded, jettisoning the baby and submersing itself in the filthy bath water. The self-worship incurred by humanist singlehood renders the monastic calling so insipid as to make no more sense than monasticism makes historically to Protestantism. But I see the error as inherited from the previous dialectical generation and do not venture to judge the unfortunate, deprived humanists of our era. Are a higher percentage of them at fault for the decline of civilization than their Western dialectical forebears? I see only disadvantage in assuming so. Reactionary critics would have humanists go backwards dialectically to an earlier rendition of corruption, merely a slope that leads right back down to where we are today. This they recommend when the entire inclination of humanists is forward-looking and progressive. That orientation is not evil in itself and shouldn’t be treated as such. To look backwards or forwards is of relative value, and either of the two can be baptized in the life of Him who would have us look upwards most of all.

III. Überfrau

It’ll take some radical effort to baptize the Nietzschean self-worship out of progressivism, I acknowledge. When the Ruth Handler character speaks of maturing beyond coping mechanisms like “the patriarchy and Barbieland,” she also reassures Barbie that her story has no end because it’s self-determined. Here Gerwig and Baumbach are engaging in cultural criticism as much as original storytelling, blurring the lines between the two in efforts to stay true to the material. A Barbie doll is played with as a technique of imagining what we want to make of ourselves. She is presented as an object of desire so as to reflect and nurture the desire we have for ourselves. She is the developed form of an adult woman for as yet undeveloped children to play with. She’s an Überfrau.

Worship of the Uncreated is not a pattern that Nietzsche rejects in his mimicry of the Christian faith. In biblical tradition worshiping created things is strictly proscribed; the uncreated God alone is worthy of worship. Nietzsche retains this dynamic but locates it within the self, refusing to worship the already created past version of oneself and identifying the not yet created future self as the Uncreated worthy of worship. This Übermensch, an aspect of oneself, becomes the principle from which is sourced meaning and purpose. And the means of creating it are dialectical reaction against everyone and everything else, the incessant breaking of past values of good and evil and the creation of new ones such that the poles of good and evil are always contained within oneself.

The life to be yearned for above all else, therefore, is defined as permanent corruption, evil always mixed with good. Barbie the movie embraces this. Weird Barbie, played by Kate McKinnon — one wonders, what are this character’s qualifications for playing the role of sage such as she does? She’s a prophet basically and lives on a mountain. She possesses the summit of Barbie-knowledge, but how? Has she had some epiphany of the Beautiful? No, quite the opposite. Whereas all the other Barbies know only good and not evil, Weird Barbie has been abused and traumatized. Her body has been tortured. Anti-theophanies of corruption’s ugly truth are what elevate the mind and soul in this society (and victimhood takes on a priestly status). This theme is reflected in the feminist enlightenment speeches of America Ferrara’s character, Gloria. Gloria realizes her humanity when she embraces the deviancy from beauty within her, the weirdness, the darkness, and beauty is redefined on this basis. Beauty having been redefined to include ugliness, and good having been redefined to include evil, truth is redefined as corruption, the mixture of darkness with light. Meaning is determined by loss of purpose.

There is supreme irony in the scene in the park that I think comprises the pinnacle of Barbie the movie. The pinnacle of this pinnacle is when Barbie sees an old woman on a park bench dressed in green (played by Ann Roth, the costume designer on Baumbach and Gerwig’s previous film White Noise) and realizes that she is beautiful, telling her so. This is so very important because it’s not an anti-theophany of trauma like Weird Barbie has had, but an epiphany of beauty. Weird Barbie may have been a helpful prophet, but it’s the epiphany of beauty that makes Barbie into the movie’s messiah figure. Taken out of context, this scene could easily be given a Christian interpretation. The woman is beautiful — she’s made in the image of God. But she responds with satisfaction, “I know.” How does she know? Does she know because this knowledge comes down to her from above, from her Creator who made her in His image? Or does she know because she takes this knowledge, and the power thereof, for herself — like Prometheus or Nietzsche or Oppenheimer?

Zoom out and take in the rest of the scene: Barbie beholds in the green parkland tableaus of human bliss and misery both, people together and alone, in happiness and agony, beauty and ugliness. It’s as if to say there is not one without the other, and this is the green, natural truth about beauty which has been ignored in pink, artificial Barbieland (despite being present in the plastic grass and trees). Optically, you see, pink is a synthetic color created in the mind but not corresponding to any wavelength of light. From an objective extrasensory perspective, the color wheel is not a wheel; beyond red and violet on the spectrum of light are infrared and ultraviolent radiation (and beyond them, X-rays and gamma rays in one direction and microwaves and radio waves in the other). The range of color we perceive between red and violet, variously called pink, magenta, and purple, thus symbolizes the sensory materialism we use to mask over and distract from invisible realities. In extrasensory fact, optically, what we perceive as pink is actually the negation of green wavelengths.2 In Barbie we’re being told, therefore, that any human conception of paradise where everything is good, and evil is expelled — not just secular utopias but also the biblical account of our origin they are meant to replace — is an untrue pink fantasy and that the green scientific truth from which pink fantasy would have us distracted is that the corruption of values is the principle of beauty to which we must devote ourselves.

But this pink-green dialectic is no less synthetic than, no differently patterned from, the dialectic of gender conflict that the movie itself tells us is illusory, fun to play with for a time maybe, but unsatisfying in the end and soul-wrecking if not overcome. Good relative to evil does not and can not retain its identity. Bliss made relative to torment will be swallowed up in torment. Good can only be good if it’s related to a principle of Good that has no relation to evil. Real bliss can only be experienced if we are created faithfully for that purpose by such a Good. The concoction of good and evil upon which Barbie’s humanism is built is unstable and does not last. It’s not true.

IV. Creative motherhood

So how do we get out of this mess? In the beginning of the film, as a parody of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the notes of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra accompany the 1959 debut of the Barbie doll as a violent force of sterile pleasure-seeking that destroys all images of motherhood. The scene functions as a neutral critique of what Barbie (and the sexual revolution at large) has meant for culture, one in which progressives and conservatives alike can see their values of good and evil reflected back at them. But the movie begins with this negative depiction of motherhood as a barrier to pleasure, fit to be destroyed, specifically so as to reject this dialectical negation. The way Hollywood screenwriting has developed, it nowadays always begins with an anti-theme, that negative state of being which the screenwriter forces the protagonist to overcome in the course of the story.3 If Barbie the doll is a symbol of sterile sexuality that obliterates motherhood, Barbie the movie wants to mature beyond that caustic dialectic.

So as long as the movie’s stance towards motherhood is “It may be mixed with evil, but there is a lot of good here that deserves to be rescued,” I would say the same about the movie itself.

By all accounts Greta Gerwig loves motherhood. Not only is she a mother twice over herself, but all three of her mature directorial efforts have a form of motherhood at their heart. In the autofictional Lady Bird the relationship between mother and daughter is the prism through which to understand the teenage daughter’s own artistic ambitions. This symbolic refraction repeats in Little Women, a story of four sisters raised by their mother during the Civil War, when the ending is rewritten to incorporate into Louisa May Alcott’s alter ego, the main character Jo March, elements from Alcott’s own experience becoming a published author. Unlike Jo, Alcott never married, never gave birth in the flesh, and yet how many souls has she mothered by way of her writings? She gives birth even today.

The beating heart of the Barbie movie is likewise made up of a mother-daughter relationship between Ferrara’s Gloria and daughter Sasha, played by Ariana Greenblatt. The story’s conflict is incited mysteriously by this relationship, and the mystical resolution (post–gender war) is patterned after it. For to find her direction in life, Barbie must learn it from her own mother, Barbie-creator Ruth Handler, here playing the role of artist as mother to her art and through her art, like Gerwig’s Jo March–Alcott hybrid. To write a story, to create a character — to make a doll — is to be a parent in type. You give them life, a name, a purpose; you provide for them along their journey. You send them out into the world to have a life of their own amongst their audience. And the process commonly requires tremendous acts of sacrifice and can be excruciatingly painful even as it exalts the soul to see human life flourish outside oneself due in part to one’s agency.

When looking at anti-patriarchal feminism (and anti-feminist patriarchy), we saw how identifying a pattern as bad and inverting it only leads to the generation of bad patterns. The healthy alternative is to find good patterns and to repeat them. When Gerwig looks to the patterns of motherly love to craft her relationships with characters, and through them, with us her audience, we receive a story with the potential to humanize — not in a dialectical way as with Nietzschean humanism, but in a typological way, according to natural law, whereby the human being is created in the image of God. By becoming an intelligent creator, an author (or dollmaker) enacts a pattern that when extended to a cosmic level declares us all to be creations of a divine author to whom we are to look to find our purpose and meaning in life.

I admit to being not a little moved when Ruth Handler offers a path of humanization to her creation, such that Barbie thereby has a vision of intimate homemade images of women in little moments at various stages of life. Indeed the mother typology is moving, but it was the form of the images that really got to me. They were analog. I can hardly stand the world of inhuman digital images that we have built around ourselves. Composed of ones and zeros, they are a thoroughly dialectical construction, designed for the purpose of easy manipulation, and representative of how computers, not humans, perceive things. When we constantly consume images like this, we become exactly like them: anti-symbolic, fractally polarized computers primed for easy manipulation. After having Little Women shot on film (quite beautifully, I might add), Gerwig chose to have Barbie shot digitally specifically for the inhumanity of digital images:

I love film. But with this movie there was something about it where, like, because it’s Barbie and because it’s plastic, there was something about the hyperreality of, like, the Alexa 65, that I was, like, “Actually, that’s what I want. I want the total saturation.” And we talked about it, and I was like, “This has this wonderful quality of like a, you know, 70mm Jacques Tati, but — it’s synthetic.” And the syntheticness is actually part of Barbie, which felt correct. It’s like a philosophical thing. Whereas, like, Little Women, that’s — we’re making a movie in the 1800s. It has to be a photochemical process because it’s, like, what they had.4

But it’s no longer what we have. This is the meaning of all the digital photography we’re constantly surrounding ourselves with and building our souls out of, transforming our humanity into a mass-produced plastic Barbieland. A simple montage of analog images dropped at the end of a movie like this hits me like a breath of air to a drowning man. It’s so sad though: in order aesthetically to represent a process of humanization we have to put away our normal tools and resort instead to methods of analog recording that we’ve largely forsaken. It’s this little reminder that we’ve abandoned typological modes of human imagery for the sake of dialectical dehumanization that really pricked my heart in that theater.

But Barbie in the end becomes human, the daughter of her mother, made after her image. The way the metamorphosis is confirmed to the audience is her arrival for an appointment at a gynecologist. Having been reproduced by a mother, she now has the capacity to reproduce as a mother. The transformation symbolizes the maturation of those who as children may have identified with the plastic toy, but who nonetheless return in their identity to the form of human beings. Hopefully the genitals aren’t bestowed merely so that Barbie can become a syphilitic like Nietzsche (a real downer of a sequel that would be!). But the acquisition of sexual capacity signals the capacity for more than just sex — more than just sexual pleasure, and more than just sexual reproduction.

V. Monastic motherhood

It helps to have genitals to be a monastic. And hormones. Being a eunuch is not helpful. The battles with eros that occur at the outset of an adult’s spiritual life prove vital preparation for the warfare against non-physical passions that happens later on. The normal pattern of human development is arranged with great intelligence, and eunuchs to whom celibacy comes as a given are at a terrible disadvantage when it comes to more advanced trials. This is not to take anything away from the importance of chastity, but… in order to transform your eros into something spiritual, it helps to have it in the first place. Chastity without that spiritual eros is like a rusty lamp without a flame (and eros without chastity, it follows, is a house on fire). Barbie’s genitals could be given to her, it should be acknowledged, so that she becomes — not necessarily a biological matrix through coupling — but instead a monastic mother radiating divine eros.

In the Church, monastic women are called mother, just as monastic men are called father. Life and death have a double meaning according to our double nature, noetic soul and sense-endowed body. The word ‘death’ in Scripture is often used not for bodily decease but for separation of the soul from God. The word covers two levels of the fractal pattern, and the higher level is more important and the source of meaning for the lower level. The same with the word ‘life’: the soul may be the life of the body, but this relationship is merely patterned after God being the life of the soul. When conflict occurs between the two, the soul’s adherence to God as the source of life is to be maintained at all costs, even if the body’s relationship with the soul is to be disrupted as a consequence; since God is the ultimate source of life, He has the power to restore the body, we must believe. So if being a mother or father indicates the act of giving life to another, someone who shines the light of the Gospel into the hearts of others by his or her way of life is performing the role that provides bodily motherhood and fatherhood their meaning.

Christ says this when he instructs the people at the end of Matthew 12. He points to His disciples and says, “Behold my mother and my brethren! For whosoever shall do the will of my Father which is in heaven, the same is my brother, and sister, and mother” (12:49–50). The disciples give birth to the Body of Christ through their apostolic labors and martyric witness, just as the virgin Mother of God gives birth to the body of Christ despite being unwedded to a man of this world. Jesus expresses the higher relationship in terms of the lower relationship, which is right, because that which is lower is the expression of the meaning that comes from above. The Mother of God is so great because she gave the seed of meaning, the Logos Himself, the lowest possible expression; she loved the Uncreated God to the exclusion of all created things so purely that He materialized in her womb. But that which is expression and that which is the Logos of meaning are not to be misidentified or disordered. Isaiah chapter 54 is about this, too, which passage begins by announcing, “Sing, O barren, thou that didst not bear; break forth into singing, and cry aloud, thou that didst not travail with child: for more are the children of the desolate than the children of the married wife, saith the LORD.” The prophecy refers to the advent of the Church, when the source of life is dispensed freely to all via virgins and martyrs and consequently the bodily generation of Israel by means of lawful marriage is revealed to be the symbolic expression of a higher spiritual meaning.

The spiritual motherhood of Louisa May Alcott, of Ruth Handler, of Greta Gerwig, as those who provide meaning for others by way of artistic creation, operates as a humanist shadow of this original Christian calling. The discipline they have to go through to achieve their lives of providence entails a degree of self-sacrifice and love, and I honor it very much. You can witness the fruit of it in the “But I’m so lonely” scene in Little Women (clip below). I remember seeing a trailer for this movie that made me dread it because it used this little feminist speech but without the final lament. Alas I needn’t have worried because “But I’m so lonely” changes everything:

After first being forced to acknowledge that loving requires sacrifice, we then receive here expression both of the femininity of humanity and the full humanity of women compounded by the confusion of a broken society that can’t hold both of these thoughts for being so far removed from love of God and neighbor. I recognize the agony, and I can identify with it, my heart burning with compassion. But I’m not captive to the same agony because by grace I’m confined in no way to the loneliness of humanism. The ambition of humanism, I’ll honestly say, is a much greater temptation for me, but let me address the freedom from loneliness. St. Herman of Alaska, patron saint of all America, lived alone on Spruce Island as a simple monk. A worldly man once asked him how he could live alone, but he replied he was not alone but lived in the presence of God and all His angels. To live in worship of the divine Image according to which we are created, rather than in worship of the world or our own human nature, is to be immune to the ravages of loneliness even if you’ve known full well what that’s like. This is true whether you’re having visions of God and His angels or you merely know by faith that they’re there. Either way you’ve taken your place in the heavenly hierarchy, and you maternally shine grace on those around you.

Our collective call to be such a mother to the Body of Christ in the world can be fulfilled through a variety of means according to the diversity of vocations. Indeed none is so profound as marriage and parenting because it comprises the deepest expression of truth. But none is so essential and potent as the monastic path because this spiritual union with our Creator sheds meaning and life on everything we do. As for the artistic calling, obviously it overlaps with the calling to mother children in innumerable ways. But in a humanist context the artistic calling frequently provides shelter for the misunderstood monastic impulse because to be monastic is in fact the highest artform and the most essential creativity. The medium is one’s entire life, soul and body coupled like husband and wife, the mind descending into the heart like the Word of God into His mother’s womb — and such a mind’s constant occupation is prayer. A Christian prays to God and His saints. But a humanist prays to herself and her fellow humans, and these communications take the form of art, be it verbal, visual, musical, or a brand of dolls.

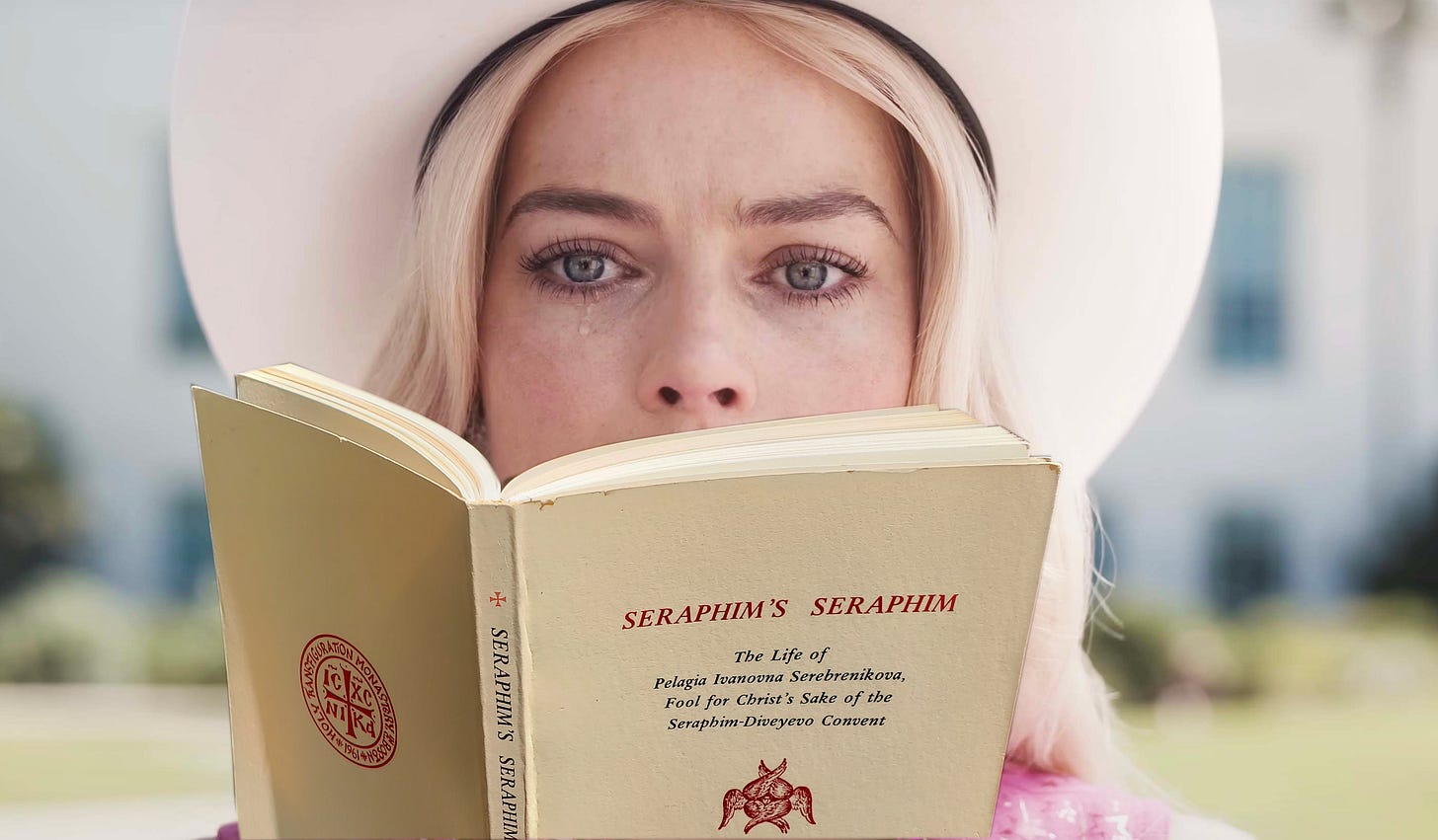

Given the character of the Barbie doll as created by Mattel and interpreted by Gerwig, marriage thus does not make sense to me as the path of conversion solving the corruption of her humanist self-worship. Gerwig perceives that Barbie’s true relationship with Ken is more sister to a brother than wife to a husband, and I think correctly so. Yet Barbie was brought into being by a mother and has received from her a purpose of being that is patterned after motherhood. Once equipped with the capacity for creation she will like Jo March yearn to fulfill this purpose. Having a personality forged in a process of humanization, a process of divinization is the natural next big step. The single women who identify with this character in her singlehood, her humanity, and her pre-divinity are answering the call to monasticism in a humanist mode. As someone who has received a call to monasticism in my life, one I have lost and wish to reclaim, my heart goes out to such fellow humans. I wish they could meet saints like the Great Martyrs Barbara and Catherine, unmarried feminine champions of humanity against the patriarchy of sin in this world. I wish they could read the Life of Blessed Pelagia (Serebrenikova), fool-for-Christ of Diveyevo, and recognize in her love, and in her rebellion against the world, the creative energy of God joined to her nature.

I’m not a poet, but the following is a poem I wrote on precisely this essay’s topic when I was 21 years old, a long time ago. It makes reference to Psalm 81:6–8, “I said, ‘Ye are gods, and all of you the sons of the Most High. But like men ye die, and like one of the rulers do ye fall.’ Arise, O God, judge the earth, for Thou shalt have an inheritance among all the nations.” But I’m referencing Nietzsche when I say, “If the gods exist, how could I bear not to be one?” — appropriating the line and recontextualizing it. Most of all, this is how, from a young age, my heavenly mother the Church taught me to think of my earthly mother and of my own creative urges emerging according to her image:

My Mother Was an Artist

(Psalm 81:6–8)

My mother was an artist,

O Lord,

But I waited.

And since birth I have yearned

To create, and be a creator

A god — like Thee, O Lord,

My God.

For if the gods exist,

How could I bear not to be one?

A creator, like my Father in heaven,

An artist, like my mother on earth,

A god, like a child of the Most High,

O Lord, I have waited.

I have written and built dreams

I have made films in my head

That caused people to tremble

But I waited.

I have poured my soul into song

Strummed harmonies and won hearts

But I waited.

I have exited windows at night

Strolled empty streets in moonlight, listening to music

Breaking hearts with the indignant poetry of my stride —

But I waited...

I have read modern novels

Which according to the authors

Is like writing them myself.

Thus, I have written modern novels.

I have created them in my mind.

But O Lord I have waited.

I have written poetry, indeed,

Which is entirely mine,

Without meter, ungainly

Proud, awkward, false

I wait

Bearing these empty words

As a suitable rebuke

For a life lived poorly.

Until I can pray,

O Lord,

I shall wait

Until I can pray.

Until I can receive Thy love, O Lord,

To create it with my life

And give it to others

To return it to Thee

As the only gift meet

Thy love, O Lord

Deeper and more beautiful

Than my mother’s landscapes

More penetrating and true

Than any portrait drawn by her

If higher praise exists, O Lord suggest it to me

My mother was an artist

And a child of the Most High

O Lord, I have waited.

(Sunday of St. George, 2001)

Barbie and Ken, after all, were named after sister and brother, the Handlers’ children. Why is it that whenever we see a man and woman together we think of them as a romantic couple, and never consider they might be brother and sister? The kiss cam don’t lie.

For the science, see this short video by Minute Physics, “There is no pink light.” The video “There’s no purple light” by This Place explains the phenomenon a bit more technically.

My article in Richard Rohlin’s upcoming Finding the Golden Key anthology is all about this topic, namely typological and dialectical modes of storytelling in Hollywood screenwriting.

Caroline Young, “Greta Gerwig Shot Barbie Digitally, And Her Reasons Make A Lot Of Sense,” Cinema Blend website, July 21, 2023.

What a wonderful article to break your short but felt silence on Substack. You put eloquently to words so many of the raw feelings I experienced when I saw this film and sensed there was more to it than critics were catching. I hope many people read this. I will certainly be passing it along. Cheers!

Phenomenal, Cormac. You have definitely expanded my perception of the movie.