I was heartened to read a comment on my last post which said, “I let the ideas reveal themselves as art, and it seems to work.” This was an inspiring response for me to hear because — well, it’s good to know what works and what doesn’t; positive feedback can be as practically useful as negative — but also because treating ideas as art is exactly what I’m trying to do.

I do not believe in my ideas. It’s essential to go over this before I talk anymore about the ideas that I have. Ideas play an extremely important part of our lives collectively and as individuals, so important that they could easily be mistaken as the things to pay attention to, the gods that rule over our lives. Well, they do rule as gods, and they are often worshiped as gods — but this shouldn’t be the case, no, not even with the good ones.

In the history of letters, different techniques have been employed to explore the power of ideas while simultaneously putting them in their place. Plato wrote dialogues. Kierkegaard used pseudonyms. Dostoevsky — a personal favorite and major influence on me — wrote novels, so-called “novels of ideas.” When you put your ideas in the mouths of fictional characters, when you place them in the context of characters’ lives, you are able to investigate ideas while remaining free of their influence. (I think Plato was doing the same thing.) And when discussing these brilliant ideas of yours, you can highlight what is actually most important: how they affect our relationships with others, whether they contribute to love or damage it.

I wrote a screenplay about ideologues: activists, authors, talking heads on the internet and television. It’s a “screenplay of ideas” in the tradition of the “novel of ideas” at which my hero Dostoevsky excelled. I wrote about ideologues because I did not want to become one, yet here I am on the internet playing indeed very much the ideologue. I’d rather write fiction about ideas than non-fictional essays and articles because I believe ideas are best treated as fiction and in fiction. Ideas themselves operate as a layer of narrative that is wrapped around the kernel of truth. They should be beautiful and harmonious, as a piece of art. They should not be an end in themselves.

But my screenplays go nowhere. I won’t complain too much here about the state of the film industry. Regardless of whether or not my screenwriting actually meets my ambitions, there wouldn’t be anywhere to send it even if it did. No one makes the kinds of movies I want to see. There are a few old masters that got their start in a bygone world that are still worth seeing, it is true. But all the points of access have been integrated into the media machine that preys on the passions of desire, anger, and ignorance as the most efficient route to winning the lucrative ongoing attention rush.

By this point, if you’re normal, you’re probably ready to suggest I write novels instead. If I could write novels I would, truth be told, but I think cinematically. If I relished describing things in words, I would describe to you why, but then I wouldn’t have to, because I’d be a novelist already, see? Writing is a necessary evil, the result of whittling down all other possible creative outlets. I do the best with it that I can.

But then what is a writer without readers? I finished one screenplay in 2020, and wrote a second one in 2021. I have a third that I began working on before either of those two, but I have not worked on it in about a year and a half. It became clear with my completed ones that the readership just isn’t there. I can hardly blame anyone — I myself don’t care to read screenplays. And asking people to read your screenplay is not something decent people do. What’s more, asking someone to read your screenplay has got to be one of the most callous, most hardhearted things a human being could do to another. I believe you will be able to recognize the Antichrist when he asks you to read his screenplay.

People will read articles. They’ll read essays. Editorials. Opinion pieces. The cynic in me says it’s because people worship knowledge as a means to power over others. I have to check myself there, of course: it is a good thing to seek understanding. Just because ideas aren’t pure Good doesn’t mean they’re evil. My literary hero Dostoevsky may have saved his grandest expressions for fiction, but he also wrote plenty of “non-fiction”: journals, essays, letters. I’ll have to get used to this real fast because as soon as in a week or two the Symbolic World website could be fixed, and when it is, I’m set to succeed Jean-Philippe Marceau as the new chief editor. Between that and my ongoing Substack efforts, this is my life now — my literary life at least.

So what do I do now with ideas like this one?

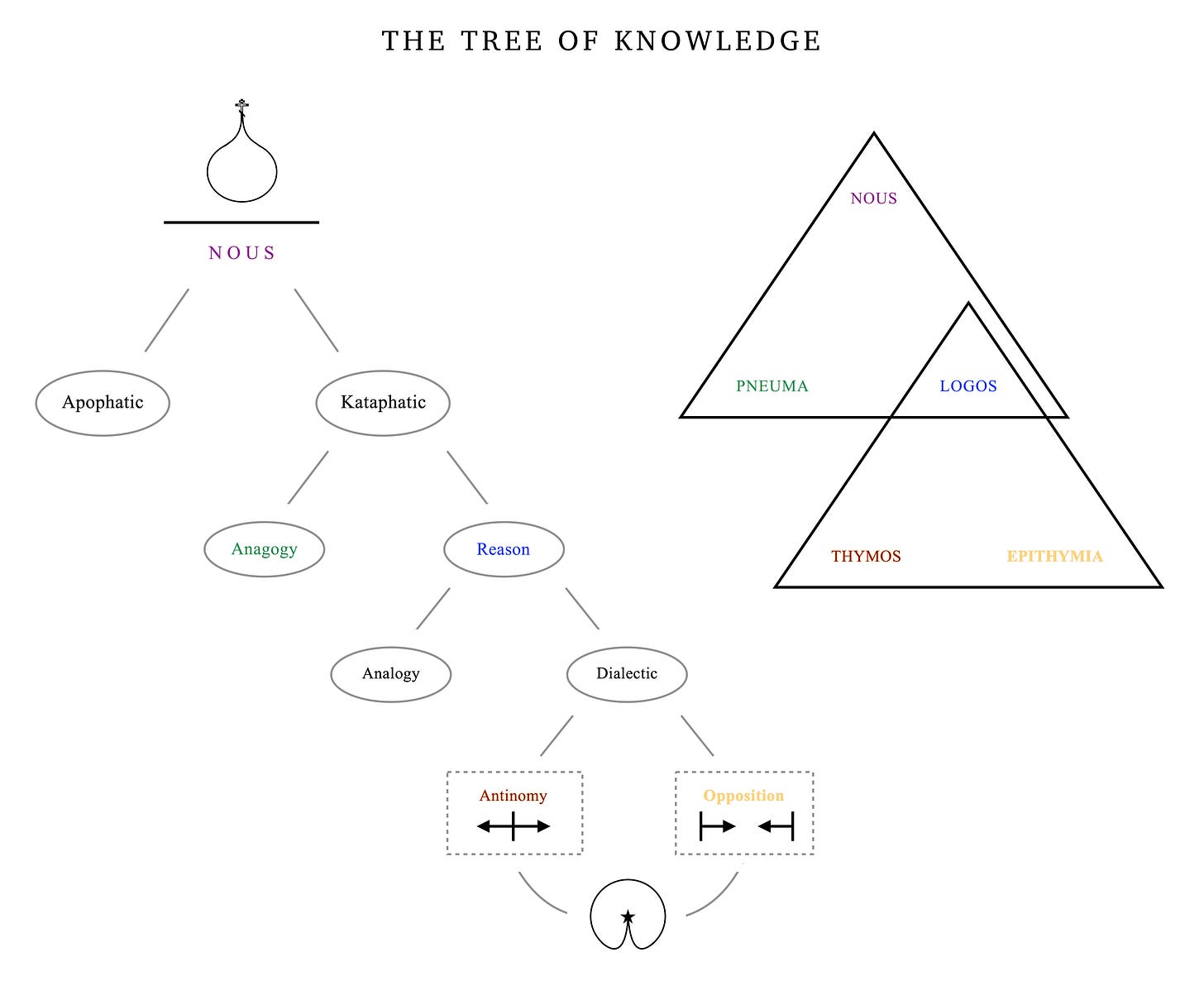

This is a very coherent pattern of all human thought, a version of which I first drew up in college. Then I read St. Maximus the Confessor’s Ambiguum 41 and found verification of the reality of the pattern in the five mediations of Christ:

The two diagrams map onto each other well. But my Patristics professor in seminary taught me to identify the second one with the Tree of Life. Honestly, a book could be written about all this. And these ideas occurred to me at a young enough age to pursue writing such a book. But I chose not to be impressed with my ideas and shelved them in favor of pursuing a life of virtue out of love for God. What good are my ideas if my mind and heart are inhospitable to God? Anyways, it was according to the very ideas that might have seduced me that I knew that life was more precious than knowledge, and that the latter will come in time anyhow to those that pursue the former.

Yeah, so I tried the life of virtue thing. Having failed that (Lord have mercy), I found myself sitting around with all these ideas lying about, wondering if I could construct anything helpful with them. I perceived a story, an intricately patterned story. Towards the end of the story, a central character meets a hieromonk residing at a woman’s monastery. This hieromonk, Fr. Benjamin, is an older Jewish man with a lively intellect, a hippy-ish background, and a thick Bronx accent (he sounds a lot like Richard Feynman, actually).1 It was in him that I discovered these ideas anew, these trees of knowledge and of life. The knowledge he deploys plays a specific role in the life of the character who visits him, a seventeen-year-old kid who is lost and hurt. What Fr. Benjamin says is tailored to his instruction and is a means to an end, a kingdom not of this world. The ideas participate in a story of victory over sadness; they are not confined to a theological tract where they participate only in themselves and other ideas. Fr. Benjamin links the pattern of knowledge with the pattern of the mind, spirit, and soul — that we may know ourselves, know what we’re here for, and know what we should do.

That’s what Fr. Benjamin did with it. What do I do with it now? Where’s my artistic purpose? How can I convey these ideas as true, not in the way that non-fiction is true, but in the way that fiction is true? I mean, where’s the subtext? Subtext I think may be the big thing that distinguishes between the fiction that I did and the journaling that I’m doing. Fr. Benjamin engages in non-verbal communication with his listener and incorporates it into how he approaches him. But where’s the subtext in a Substack essay? How can I let my ideas reveal themselves as art?

I have known many Jewish converts to the Orthodox Church, and several have played formative roles in my life.

Congrats and thank you for stepping up as the cheif editor for the SW Blog. I look forward to the road ahead.

I appreciate you sharing your wrestling with the various creative mediums. I have similar struggles too. I prefer telling someone a story over conversation than writing it down by myself. And many of the project ideas I have are not as suitable for a book, but rather as film and graphic novels and music concept records. Yet, writing is a means to these ends. I've been processing this struggle and journey to sort this out in my Substack letters to a marginal level of success. For some reason writing it out and pressing the 'publish' button challenges my assumptions and fears. It's confessional. Perhaps it could aid you as well.

Anyway, I love reading your posts and articles. I beg of you to continue them. I'll forgive you if you don't, begrudgingly.

I was hoping to support you financially, yet somehow my pledge didn’t link to a donation page. Did I miss something?