This is a paper I wrote for a history of photography class in April 2002 (that year’s historical context will be important, so keep that in mind). Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven is in my inner circle of greatest movies ever. It’s the rare kind of film that I can think about forever without ever exhausting the experience of watching it. Whenever I see it, each time, the beauty of the tragedy and the tragedy of the beauty happen to me all over again. And Lewis Hine, for the timeless iconography of his images, for all the documentary work he did in my hometown of Pittsburgh, and for his inestimable contributions to promoting child labor laws, is my favorite photographer.

The positive approach to humanism that I employ here, meanwhile, represents what a young Orthodox Christian in a collegiate environment hostile to his faith can achieve when he knows how not to react dialectically to the dialectical humanism accosting him from all sides. Exercising my Christian freedom to take such a perspective as the one in this paper was indeed integral, I feel, to the preservation of my faith throughout my college years. I say this not just to indicate a crafty strategy for surviving society, but to show the path I believe is necessary for one’s own spiritual well-being. As I wrote a few weeks ago in my Paul Barnes piece, before one can be Christian, one must be human, and that may entail appreciating human beauty non-judgmentally alongside those who worship nothing but.

I. The Opening Title Sequence

To help recreate the rural world of industrial 1916 America for his 1978 film Days of Heaven, filmmaker Terrence Malick accessed his private collection of photographs from that era. “Eventually,” reports the film’s cinematographer, “we felt these [photographs] to be such an influence that they were the first images chosen for the audience to see during the title sequence, thereby setting the mood and sense of period for the picture.”1 This title sequence, nearly two minutes long, consists of 25 still photographs, about three-fourths of which are by Lewis W. Hine (1874–1940).

Indeed, Hine’s images create the tenor of the introductory piece, but the context in which they are set — the context both of the sequence by itself and of the film at large — select and amplify certain aspects of the photographs, while eliminating others. Hine was a social reformer who primarily intended his humanistic images to have their effect in the present tense across the spatial dimension of the United States. The desired effect was to create a human community between all Americans of his time, especially those like immigrants and child laborers who were neglected and oppressed. Malick, however, is not a reformer but an artist and a storyteller, one who imaginatively recreates the past. While muting the spatial, social effect of Hine’s images, he elicits their temporal power to create community between generations. This power descends from the same humanism that Hine invested in his images for the purposes of contemporary social reform, but only with time has it come to light. In truth, it is a tribute to Lewis Hine that his images have the capacity to bind people together in a common humanity across both space and time. It is likewise a credit to Terrence Malick that, while recontextualizing Hine’s photographs and transforming their meaning, he yet remains true to the images’ incipient humanism.

II. The Original Function and Context of the Photographs

Some eighteen Lewis Hine photographs comprise Malick’s imaginative intro (this paper will only touch on a couple); in origins they range from various parts of Hine’s career. Perhaps the earliest image used is his famous 1905 portrait, “Young Russian Jewess at Ellis Island” (fig. 3). Hine first went to Ellis Island as an instructor at a progressive educational institute, the Ethical Culture School. Disturbed by the anti-immigrant fervor of the general population and especially of the media, while moved by the unmerciful plight of immigration, Hine utilized photography in a classroom context to encourage Americans to welcome immigrants by exhibiting their humanity and their unique voices (visually speaking, of course).

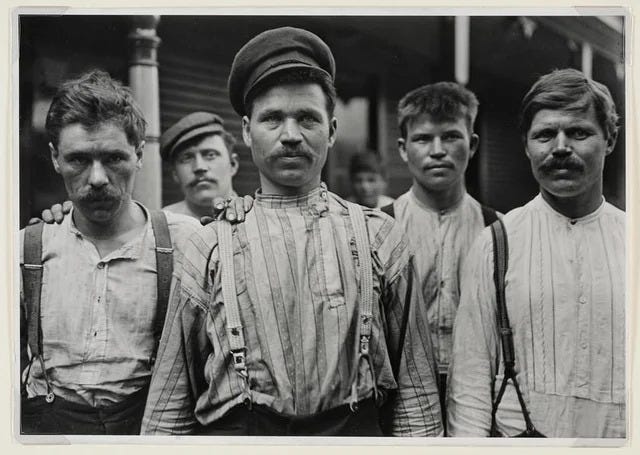

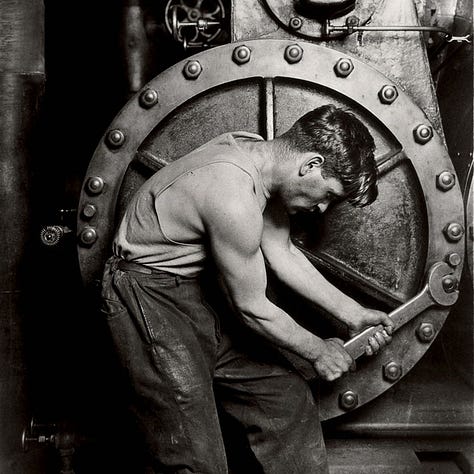

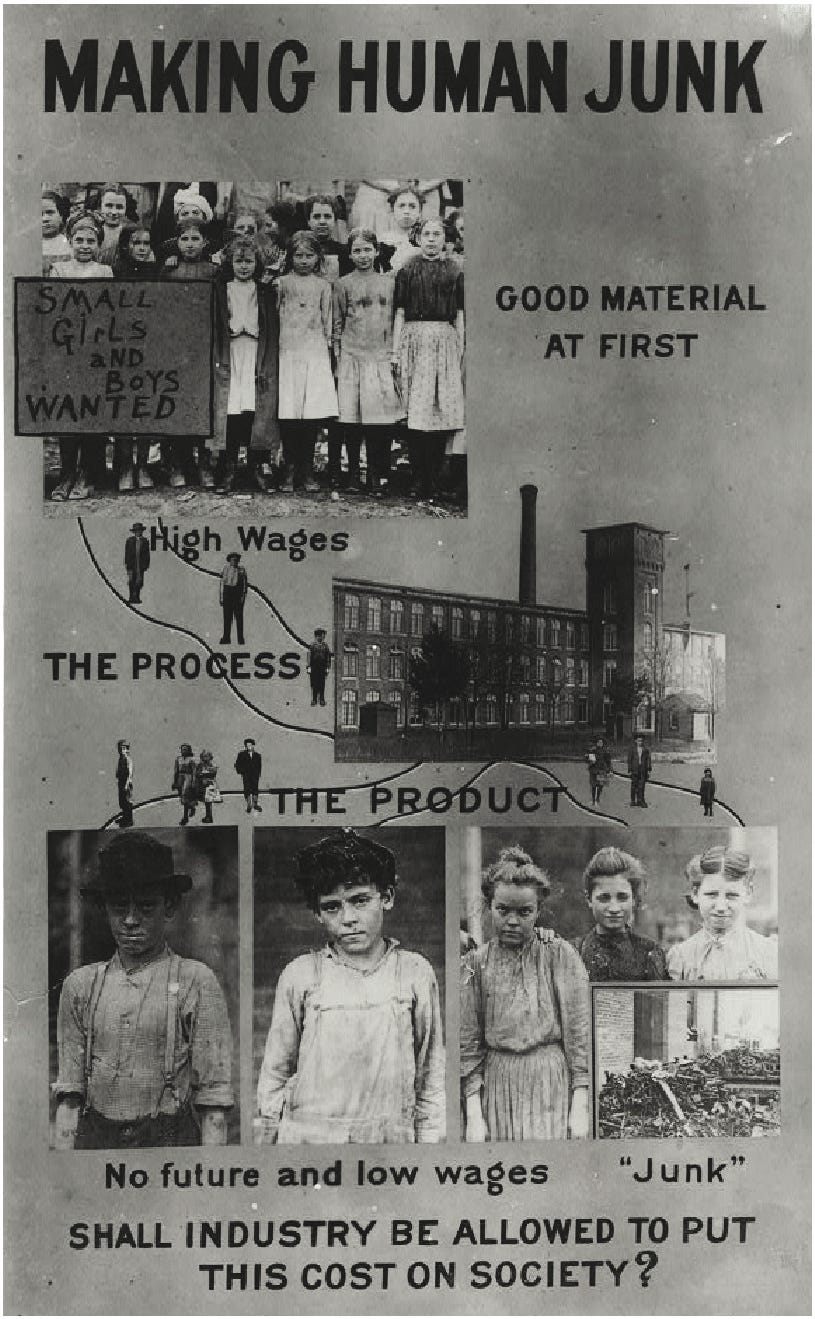

Having met success at Ellis Island, within a few years Hine had become a professional photographer in the social reform movement. The context of the classroom, though, forever lingered with Hine, who wrote, “I held that I was merely changing the educational efforts from the classroom to the world.”2 The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) employed Hine from 1906 to 1918, during which time he also did prominent work for the Pittsburgh Survey (1908). Two important Pittsburgh shots, “Young German steelworker, Pittsburgh” and “Steelworkers at Russian boarding house, Homestead, Pennsylvania” (fig. 1) were used in Days of Heaven. Images like these appeared in the Pittsburgh Survey’s six thick volumes, the gist of which was to portray all aspects of social life, but not merely in an abstract, indexical fashion. The investigators sought to vivify their data with accounted experiences, biographies, and an overall personal stamp believing that if the “hell-with-the-lid-off” social reality of Pittsburgh at that time was shown in scope and in its poignant human dimension, social reform would naturally follow. Hine’s NCLC photographs (which Malick avoids or eschews for reasons explored later) similarly illustrated propagandistic exhibitions, magazines, reports, pamphlets, and such. Scientific biographical data that Hine assiduously recorded often accompanied the images. The combined effect of the mounting data and number of images was very powerful, and the photographs in this context insistently directed their audience primarily toward one thing: social reform, now.

III. The Form of the Images, and a New Function

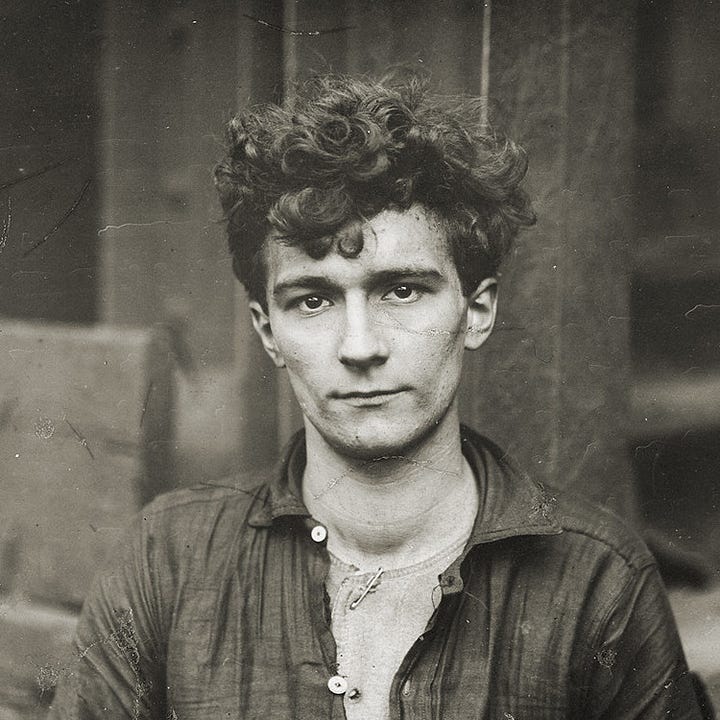

Hine’s form followed his function. Endeavoring to reach out to the oppressed and include them in humanity, he developed a style that can be described as iconic and additive. He would pose his subjects frontally, in their environment, with a distance that grants them the autonomy and dignity of personhood. His images compare well with Byzantine and Russian iconography, as here with the Russian steelworkers from Homestead (fig. 1) and the famous Ravenna mosaics of Emperor Justinian and entourage (fig. 2). The form of both these images is such that the composition is additive; that is, one can keep adding figures without disrupting the balance of composition (or subtracting, as has been done to the detail of the Ravenna mosaic). Indeed, often in mines and factories Hine would gather numbers of children for a portrait, adding whoever came along. His style allows for that. The figures of an iconic, additive portrait exist in an inclusive reality. The mosaic includes the churchgoer in the kingdom of heaven, while the Hine portrait includes the immigrants and those looking at the photograph — Hine’s “pupils” — in the kingdom of America. Later generations look at the image and are included with the immigrants in a single nation.

In this way does Hine’s form follow his function, that of social reform. And in this way does another function, given time, emerge from the form: that of cultural and national memory. Hine himself recognized it late in life when he reviewed his entire career and proposed a project that took as a starting point the accumulative effect of his work. The project was never funded, but one supposes it never had to be because the accumulative effect of his work is indeed extant. Tellingly, he referred to the project with the words, “Ever — the Human Document to keep the present and future in touch with the past.”3 After his death, in the decades leading up to the making of Days of Heaven, Hine’s images slowly began to form a national memory. A writer promoting Hine in 1967 noted,

In recent years, curiously enough, more and more Hine photographs appear and re-appear — as if surfacing from some insistent background undercurrent. Hine photographs illustrate TV specials. Labor union advertisements use them — to sentimentalize the past and usually with no credit to Hine — but use them. So, too, with book illustrations and magazine articles. Life used a double spread of Hine photographs when it celebrated the 50th anniversary of the founding of the NCLC in 1954 — identified him in the text but never indexed his name. And most recently Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium Is the Massage [1967] used a Hine photograph without credit or reference — or probably the knowledge that it was a Hine photograph.4

IV. The Context of the Film: Tragedy and Mythology

Malick’s Days of Heaven was released in 1978, over a half-century after the images of its title sequence were taken. The film is a mythological rendering of the American past as well as a tragedy; every joint of its structure is leavened with tragic irony. The dialectics involved include most prominently those between society and nature — or society and the individual — but also (as the title implies) those between time, death, and eternity.

The film opens when the main character Bill accidentally kills a factory coworker in a fight; he, his lover Abby, and his 9-year-old sister Linda promptly flee their industrial Chicago environs. Hopping a train, they land in the wheat fields of the Texan panhandle, but though they seek escape from society and industry they are nonetheless drawn into a countryside peopled everywhere with migrant workers and steamed with imposing, turn-of-the-century farm machinery. To avoid scandal, Bill and Abby tell people they are siblings.

From here, the story resembles roughly the premise to Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove. A bachelor farmer sees Abby among his sackers and falls for her. Having secretively learned that the young farmer, Chuck, is dying, Bill encourages Abby to accept Chuck’s invitation for her and her siblings to stay on after the harvest. The four live on the farm together as the farmer’s romantic advances increase. One day, Bill reflects with Chuck on how he once realized that he was not the smartest guy in the world and that he was never going to make a big score, though growing up he always thought he would. The next day, in private, he convinces Abby that she should accept Chuck’s marriage proposal with the assurance that within a few months the farmer would die. They marry, but he does not die. To the contrary, with Chuck’s persistent loneliness gone, his health improves. Time goes on as suspicions build in Chuck and tensions emerge between Bill and Abby. Eventually Bill leaves the farm, and for the rest of the winter and through till summer Chuck, Abby, and Linda have the farm to themselves.

Chuck’s tragedy is that though believing in Abby as the cure to his loneliness, he never really knows her. Abby’s heart becomes torn between two men, but the man she is with she cannot properly love. With harvest season and a new crowd of workers, Bill returns, apparently with the motive of moral resolution. Alone with Abby, he admits that he never knew what he had with her, and they consent to part. Though this parting could be the one thing to grant Chuck happiness, he catches their farewell from a distance, misconstrues it, and convinces himself he has been betrayed. Madness quickly descends upon the farm (à la Euripides’s Herakles) in the form of a locust swarm, followed by a raging fire when amidst the commotion of fighting the locusts, Chuck accosts Bill with a gas lantern. After confronting and turning on Abby, Chuck with a gun goes again after Bill. He dies when Bill defends himself with a metal tool.

Bill, Abby, and Linda flee in parallel with the beginning, accompanied by the same jubilant Leo Kottke music that first greeted them in Texas. None of the film’s characters thinks of himself or herself as belonging to a people, but only as an individual. Rebellious and free, they again escape into the wilderness, this time down a river, and again they can hide neither from society nor their social responsibility. There are people all over the river. In the late 1910s it is no longer the Wild West, and law and order prevail. Bill gives the cops a good chase, but he is shot dead when trying to break across the river.

This then is the film that Lewis Hine is contracted to introduce. Stylistically the film and the photographs are diametrically opposed, further leavening the story with tragic irony. Hine’s images exist in a silent, black-and-white stasis, representing a past that is dead, if vividly remembered. The music and dynamism of life, on the other hand, characterize Malick’s style, his camera always moving and his colors glowing. Where Hine is frontal and iconic, Malick is elliptical and lyrical. By incorporating Hine into the film’s beginning, Malick uses his icons as a kind of surface to his own ellipse.

By Malick’s “elliptical style” is meant the way the emotions and events of the story are eschewed in favor of the flow of society and nature around them. If a consequential discussion were taking place, Malick would rather show chickens in the wheat field or the workers playing baseball. Then the conversation would be alluded to in passing, heard in mumbled fragments. In this way are the characters absorbed into their environment, into either the wild nature in which lies the illusion of their freedom and individuality, or the law-regulated society in which “human voices wake us, and we drown.” This T.S. Eliot line is more than appropriate considering the film’s climax. When Bill is shot dead the film achieves a silent stasis akin to Hine. Bill hits the river face down, and an underwater camera catches the instant of his plunge from directly beneath him, so that the shot of him is frontal, showing his face, shoulders, and chest against the soft blue sky. For this fleeting instant the surrounding noises are silenced; even the sound of his body hitting the water is omitted.

The death of the main character, therefore, brings the film back to the stasis from which it came, fulfilling the tragedy, but the film continues with an epilogue. Abby and Linda go to a town where Linda is placed in a boarding school. Nothing is learned of Abby’s destiny beyond her boarding a train headed out of town. Linda, who throughout the film has in voiceover been giving a past-tense narration parallel to that of the film, escapes the boarding school and runs away with a teenaged friend she has known from the wheat fields. Over the closing music Linda says of her fellow traveler, “This girl, she didn’t know where she was going or what she was going to do.” There ends the film, leaving the characters without a future; nor at any point in the film were they given a past.

As a mythology of a bygone era, it is essential that the story and its characters are isolated to their own moment in time, just as all humanity is isolated in a moment of time. Those of us watching the film at present, severed from our past and future, are at least united in this common condition, and this cross-generational union should not be undervalued. It is according to the tragic irony of the film that in temporally severing the characters from their audience, it unites them. “United in our diversity,” is a phrase often used by the current American president [2002]. He speaks of a contemporary political union, but the same can be said of the various American generations. In such a way is the structure of Days of Heaven additive in the way that Lewis Hine’s portraits are additive. It reaches out and includes.

The key to this aspect is the character of Linda. The two main elliptic arches by which the viewer skirts the story are the cinematic excursions into nature and society, into which the characters are absorbed. Linda’s narration, however, is another arch, equally elliptical; narration is only its secondary or tertiary purpose. In the voice of Linda, the viewer and characters have an alternative substance into which to be absorbed, and mercifully it is the concrete perspective of a human person. Linda is the way out, and suitably she also forges the link between Lewis Hine and the greater body of the film. She seems to be intentionally created as the quintessential Hine kid. Gruff and streetwise, quirky, morally precocious, with a biting accent and picturesque face, she is random in her thoughts. In fact, to the end of the title sequence featuring so many Hine photographs a final portrait of Linda is attached, done in similar style. So she emerges from this stasis of the past and forms the consciousness with which the viewer is left, not knowing where to go or what to do.

V. Finally, the Form and Context of the Title Sequence

Photographer and critic Allan Sekula wrote of Lewis Hine in his 1975 essay “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning.” Undoubtedly, he would have hated the use of Hine’s photographs in Days of Heaven. To begin, he admits the two functions of Hine, saying,

Hine is an artist in the tradition of Millet and Tolstoy, a realist mystic.... What these two connotative levels suggest is an artist who partakes of two roles. The first role, which determines the empirical value of the photograph as report, is that of witness. The second role, through which the photograph is invested with spiritual significance, is that of seer, and entails the notion of expressive genius.

He then goes on to say, however, “It is at the second level that Hine can be appropriated by bourgeois esthetic discourse, and invented as a significant ‘primitive’ figure in the history of photography.”5 Maintaining that a photograph’s meaning is determined by the context, Sekula cannot believe that a Hine photograph removed from the context of social reform could retain any of its original significance. Meanwhile, such a displacement is precisely what Malick insists on doing.

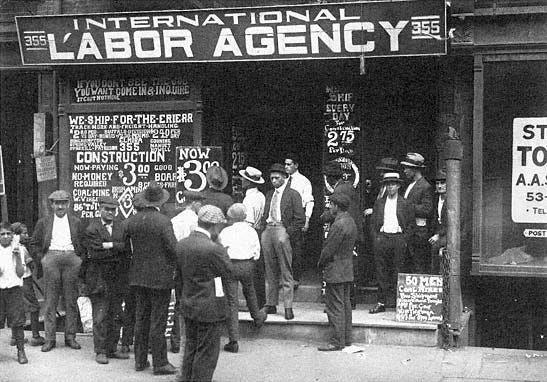

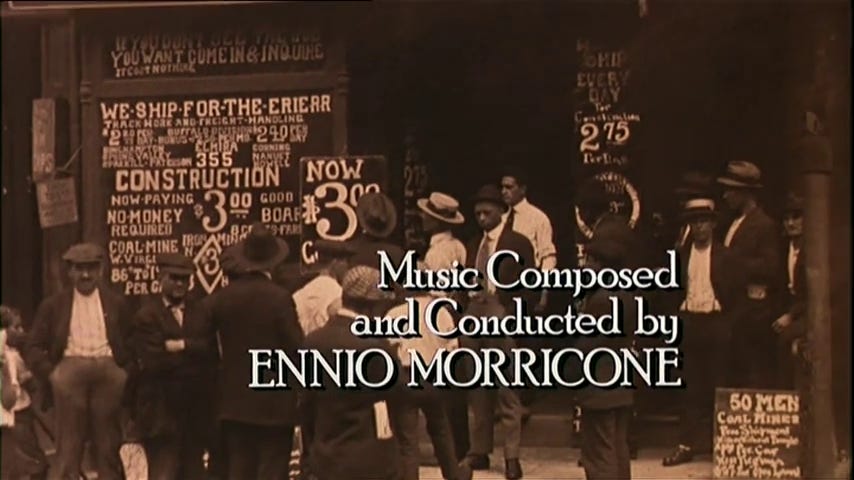

All the photographs used in the title sequence are cropped to fit the screen’s 1.85:1 aspect ratio. In being cropped many of the portraits are removed from their environment, which Hine included specifically for his social message. As seen in the movie, the Russian Jewess might not be at Ellis Island at all (figs. 3 and 4), but the iconic function for the most part remains. The most blatant example of excising the social message, however, comes with Malick’s use of the 1910 photograph “Labor Agency, New York City,” in which the building’s large sign — “INTERNATIONAL LABOR AGENCY” — is entirely omitted (figs. 5 and 6). The moviegoer still sees a group of men looking at a sign with employment information, so the content is still there; but the image no longer screams for reform. Instead, the days of unemployment are romanticized.

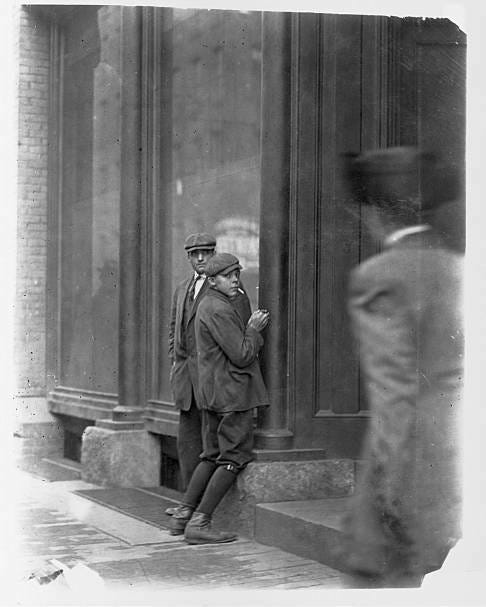

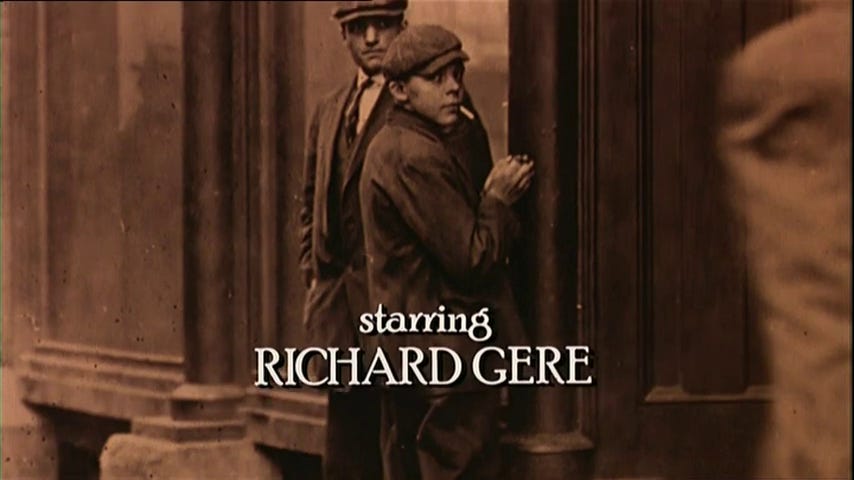

Besides cropping, Malick also pans and zooms the photographs, referencing the dynamic camerawork of the film. Also the images dissolve from one to the next, the favored cut between scenes throughout. Sepia tone is used on all the photographs, a manipulation that could only be for nostalgic reasons. In fact, nostalgia and a fantastical vision of the past are confirmed as the sole purposes of the images by every formal and contextual manipulation. The musical accompaniment is Saint-Saens’s “The Aquarium” from Carnival of the Animals — a perfectly dreamy piece that hardly inspires social reform. Neither do the credits flashing across the scene help distract the viewer from realizing he is partaking of Hollywood fantasy. The first image after the title is a kid on the street smoking a cigarette. Hine’s original notes might have given the boy’s name and how long he had worked as a carrier or a newsie. Here the viewer reads, “Starring Richard Gere.”

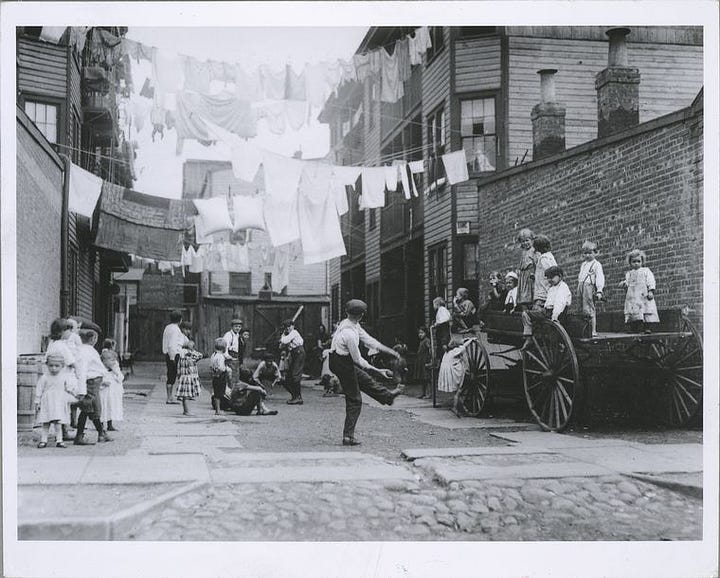

But the other photographs added to Hine’s do the most to alter their meaning. The first is William Notman’s 1884 “Ice Palace, Dominion Square, Montreal.” The fantastical image is included as a prefigurement of the farmer’s Victorian house that dominates the landscape and serves as a metaphor for the structure of the film. But its Pictorialist nature appropriates Hine into a “bourgeois esthetic discourse” — as do the rest. Frances Benjamin Johnston’s portrait of a bride trailing a veil across her face offers an ideal of late-Victorian beauty. Chansonetta Emmons’s “Dorothy on the Rocks at Ogunquit, Maine” from 1910 is downright Romantic (it appears with the words, “Director of Photography / NESTOR ALMENDROS”). In such a discourse, Hine’s images — such as that of the flock of white laundry hanging between buildings and that of the group of kids playing baseball in the alley — are utilized solely as the spiritual expressions of a seer, to use Sekula’s words. Their status as reports of a social witness is muted. This much has been gone over already, and hopefully this essay shows that this liberal use of Hine does not diminish the value of Malick’s film.

Hine’s photographs remain icons of humanism in contrasting contexts because they reach out into both time and space. In truth the images receive fullest meaning in their original context where both the temporal and spatial elements shine, but isolating the temporal does not betray the spatial. Malick is simply not interested in reforming a bygone society. He is, however, interested in enriching and reforming his own times. Certainly, by Sekula’s standards the title sequence is laughable, if not lamentable. He writes, “The celebration of abstract humanity becomes, in any given political situation, the celebration of the dignity of the passive victim.”6 This quotation is key, for in it Sekula dialectically opposes mythology and activism, humanism and humanitarianism, and, by extension, tradition (something transtemporal like mythology) and democracy (something concerning merely the present, like activism) — an opposition purely of Sekula’s creation and not necessarily the case at all. A more adventurous soul can achieve both. The Englishman G.K. Chesterton once wrote,

I have never been able to understand where people got the idea that democracy was in some way opposed to tradition. It is obvious that tradition is only democracy extended through time.... Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.7

To clarify, consider the political and social relevance of Days of Heaven. Americans, like the characters depicted, have for too long not seen themselves as a nation, but as individuals free to escape and hide within our own landscapes. As such we have shirked our social responsibility as a people in a global community. Only recently have we learned what it means “when human voices wake us, and we drown.” Tocqueville said that America was great because America was good, but if America ever ceases to be good, it will cease to be great. That is, if America does not realize its global responsibility, its freedom will prove illusory. Malick’s style of social reform works counter to Hine’s, but the two complement each other. Hine reconciled people across space at a single time so effectively that his influence spreads through time. Malick binds generations of a single space together through time effectively enough that his influence may yet spread through space. His form is capable of that function; it just awaits the proper context.

Nestor Almendros, “Photographing Days of Heaven,” American Cinematographer (June, 1979), p. 564.

Lewis Wickes Hine, America & Lewis Hine (Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture, Inc., 1977), p. 17. Quoted in Naomi Rosenblum’s biographical notes.

Ibid., p. 136. Quoted in Alan Trachtenberg’s essay.

Judith Mara Gutman, Lewis W. Hine and the American social conscience (New York: Walker and Company, 1967), p. 50.

Allan Sekula, “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” 1975. Excerpted in Vicki Goldberg, ed., Photography in Print (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1981), p. 472.

Ibid., p. 473.

G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1927), pp. 84–85.