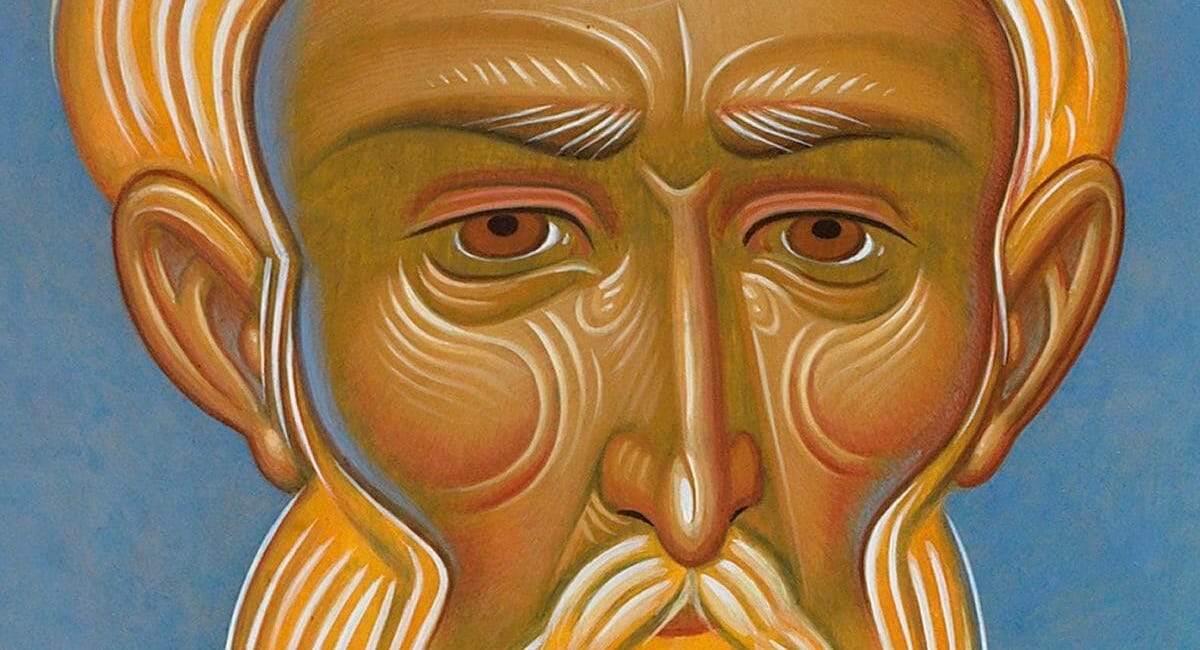

Peter, James, and John

The symbolic meaning of the recurring triad

The Patriarch Abraham sends a servant to find a wife for his son Isaac from among his kinsmen, adjuring him to swear by “Yahweh, the God of heaven and the God of the earth” (Gen. 24:3). The servant does as he is told, except once in Nahor, the servant prays rather to “Yahweh, God of my master Abraham” (24:12).

To the Patriarch Isaac, Yahweh appears and identifies Himself saying, “I am the God of Abraham thy father” (26:24). Since the division of Babel and the founding of the Seventy nations, gods were of nations. This was new that there would be a god of a single person, but the God who created heaven and earth was creating through these patriarchs a new nation through which the Seventy might be saved.

To the Patriarch Jacob, then, God says, “I am Yahweh, the God of Abraham thy father, and the God of Isaac” (28:13). To Moses God introduces Himself in the burning bush as “the God of thy father: the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” (Ex. 3:6). King David prays to “Yahweh the God of Abraham, and Isaac, and Israel, our fathers” (1 Chr. 29:18). The Prophet Elijah too prays to “Yahweh, the God of Abraham, and Isaac, and Israel” (3 Kgdms. 18:36). King Hezekiah admonishes the sons of Israel by letter to return to “the God of Abraham, and Isaac, and Israel” (2 Chr. 30:6).

When making the point to the Sadducees that the dead are raised, Jesus quotes His own words to Moses, “I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” (Matt. 22:32; Mark 12:26; Luke 20:37). Peter, in his capacity as chief of the Apostles, preaches at the Temple, “The God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and of Jacob, the God of our fathers, hath glorified his servant Jesus” (Acts 3:13).

The triadic paradigm of Tabernacle worship

The revelation and construction of the Tabernacle, the sanctuary designed as the means by which the people of Israel interact with their God, frames the whole fifth part of the five-part structure of Exodus. A heavenly vision becomes incarnate, made of dazzling colors, gold, and precious stones, attended to by a holy priesthood garbed in wondrous vestments. As an omega-cycle, this is the descent of the heavenly Jerusalem in type.

Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob/Israel comprise a holy triad, set apart as indicators of the proper way to approach God’s identity. They map onto the triadic pattern of the Tabernacle as revealed to Moses as the proper way to approach God. As Origen writes,

I think, moreover, that this threefold structure of divine philosophy was prefigured in those holy and blessed men on account of whose most holy way of life the Most High God willed to be called the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob [Ex. 3:6]. For Abraham sets forth moral philosophy through obedience; his obedience was indeed so great, his adherence to orders so strict that when he heard the command: Go forth out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and out of thy father’s house, he did not delay, but did as he was told forthwith [see Gen. 12:1–4]. And he did more even than that: even on hearing that he was to sacrifice his son, he does not hesitate, but complies with the command and, to give an example to those who should come after of the obedience in which moral philosophy consists, he spared not his only son [see Gen. 22]. Isaac also is an exponent of natural philosophy, when he digs wells and searches out the roots of things [see Gen. 26:12ff]. And Jacob practises the inspective science, in that he earned his name of Israel from his contemplation of the things of God, and saw the camps of heaven, and beheld the House of God and the angels’ paths — the ladders reaching up from earth to heaven [see Gen. 28:10, 17; 32:2].

(Origen, The Song of Songs: Commentary and Homilies, td. by R.P. Lawson [Paulist Press, 1957], pp. 44–45.)

Purification, illumination, and perfection

When Evagrius of Pontos — a learned disciple of many saints who in the late fourth century sought and received much ascetic wisdom in the Egyptian desert — sets out to write on the topic of practicing the life in Christ, the praxis of the virtues, he places it in context as the first rung in a threefold program. “Christianity,” he opens his

As the patristic tradition lays out, this threefold pattern Origen identifies as ethical, natural, and inspective corresponds to what St. Dionysius calls purification, illumination, and perfection, or what St. Maximus the Confessor calls practical philosophy, natural contemplation, and theological mystagogy. It’s the same heavenly paradigm as the Tabernacle: Abraham’s faithful sacrifice corresponds to the sacrifices in the courtyard; Isaac’s well-digging, his unearthing of the water of life underlying all things, corresponds to the golden fields of light hidden in the Holy Place; and Jacob’s vision of the angelic stairway corresponds to the Ark of Testimony crowned with cherubim in the Holy of Holies.

And in the New Covenant, these roles are taken over by Peter, James, and John — those who, according to the Apostle Paul, were reputed to be pillars in the apostolic community (Gal. 2:9, where they are named “James, Cephas, and John”). The James he’s referring to, of course, is the brother of the Lord (son of Joseph by a different mother), leader of the Christ-believing Judeans at Jerusalem. In comparison to the Gospel text, this James appears to have resurrected the symbolic role left by the son of Zebedee, John’s older brother James, after he was martyred early on by King Herod, he being the first of the Twelve to suffer death and the only one to do so within the text of Scripture (Acts 12:2). In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus multiple times draws Peter, James, and John apart for special revelations (that’s James the son of Zebedee). It happens at the raising of Jairus’s daughter (Mark 5:37, Luke 8:51), the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor (Matt. 17:1, Mark 9:2, Luke 9:28), and the agony in Gethsemane (Matt. 26:37, Mark 14:33). In almost all these instances, the order of the names is Peter, James, and John. (At the Transfiguration account in Luke 9:28, it’s uniquely “Peter, John, and James,” and at the Gethsemane account in Matt. 26:37, it’s “Peter and the two sons of Zebedee”). On these occasions of special revelation, Jesus is deliberately using these three disciples to model the proper Tabernacle pattern of approaching God.

Peter

Peter is the chief of the Apostles. That is not to say that he maps onto the Holy of Holies in this schema. Peter is chief because he goes first; he is the leader — like Abraham. Abraham, through his obedience, his faithfulness, his hope in the resurrection (Heb. 11:19), is accounted father of all those who believe in God. It can be said of his progeny no less than of him that, through their messianic seed (Jesus), they become father of all the nations, but Abraham is the earliest and first this can be said of. When the faithful arrive at the Tabernacle to approach God, they don’t stroll directly into the Holy of Holies. The courtyard is the leader, in the sense that it comes first. At the gates of the courtyard the people do gather, and they offer there the sacrifices that bind them to the Lord.

Insofar as the Christian body of the faithful is to unite around Peter as their apostolic leader, this is the symbolic capacity in which that is done, the spiritual meaning of it. Peter led all the apostles in proclaiming that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of the living God (Matt. 16:16), and on the rock of this confession, the Lord builds His Church. That is to say, Peter symbolizes the foundation: not the apse, not the dome, but the foundation. He’s not even the Church, but the rock on which the Church is built — the same way the courtyard is not yet the Tabernacle, but the sanctified space that allows the Tabernacle to be erected on earth. In the triadic stages of the spiritual life, this sanctified space corresponds to purification, the sacrifices one must make to separate from the world and be united to God’s Body, like Abraham. This is what Peter symbolizes in the Body of the Church.

James

The Apostle James represents what comes next. In the Tabernacle paradigm, that’s the heavenly Holy Place, with its seven-branched candlestand illumining the golden walls like the seven planets, the table of the bread of presence with loaves stacked in two piles of six like the constellations of the zodiac, and most of all the altar of incense before the inner veil. The Apostle James, son of Zebedee, is taken by Herod and executed for his faithfulness to Jesus (Acts 12:2), leading the way among the apostles in their martyric unity with the Lord Messiah, who was crucified, died, and rose again. This manner of death, illuminated with the supernatural energy of the Lord, is whither the apostles are to go after their Petrine confessions of faithfulness. This is how the Tabernacle is erected in the courtyard. Or the Temple in its courtyard.

The Apostle James, brother of the Lord, resurrects this symbolism after the son of Zebedee’s death, in part by himself being thrown down from the top of the Temple and surviving unharmed (see Oct. 23). For Christians are not undone by death, and neither is the symbolism of James. The temporal pattern of preparation, sabbath, and Lord’s day makes even more sense here than the spatial pattern of the Tabernacle. It’s the same heavenly pattern; so the sabbath, the day the Lord rests and creation finds its limit, the day on which the Lord Messiah rests in the tomb and harrows hades, performs the same illuminating function as the Holy Place in the triadic schema of the spiritual life. The son of Zebedee shows the way in being baptized in the death in which the Lord is baptized, drinking the blood of life from the cup of suffering (cf. Matt. 20:22–23) — in fulfillment, it can be said, of the Patriarch Isaac drinking the water of life from his wells. This is how the light of illumination is achieved; the Lord rests in the earth, but is brought up again, all of hades being harrowed along the way.

The brother of the Lord leading the Christian community in Jerusalem fulfills this same symbolism — Jerusalem which should be the holy city, but which, in that it slays the prophets and stones those that are sent to it, resembles rather the kingdom of hades. After the brother of the Lord is thrown from the height of the Temple for boldly proclaiming Jesus as the Messiah, and rises unharmed because Christ is risen, the Judeans present proceed to stone him, just as the Lord lamented (cf. Matt. 23:37). Still he does not die though, not until a man strikes his head with a fuller’s club, because only with a piece of wood like the Cross can James’s victory be accomplished.

John

Death is not the end, of course, and so the Apostle John, beloved of the Lord, represents the resurrection after the sabbath, the beginning of a new creation, the Holy of Holies where God makes Himself known between the cherubim above the covering of the Ark. As the Patriarch Jacob sees the steps reaching from earth to heaven, and the angels ascending and descending on them (Gen. 28:12) and later wrestles with a divine Man who names him Israel (Gen. 32:25–31), so John the Theologian sees the Word made flesh and reclines on His breast. John is the youngest of the apostles because he has all the life of God in him. He alone among the Twelve does not flee at the time of the Crucifixion. He stands with the Virgin Mother of God at the foot of the Cross and suffers everything she does, being worthy to be named her son and protector.

For this cause, He alone among the Twelve does not die a martyric death, having died already at the Cross with Jesus and His mother. Raised again with the Lord, he does however suffer in the hades of this world, miraculously surviving executions, slave labor, and exile to the island of Patmos, where “in the Spirit on the Lord’s day” (Rev. 1:10) he receives revelation of the end of all things. Virginal like the Lord’s Mother, and thus being only questionably subject to death, in the end, having been released from Patmos and returned to Ephesus, he yet does not look away from death (also like the Lord’s Mother) but in love joins the Lord in His death, following the pattern of the Dormition of the Mother of God. He dies peacefully in old age and is buried in a tomb, only later to be discovered to have been taken up whole, leaving no remains, already experiencing the general resurrection.

John among the apostles represents perfection, the completion of all things. The resurrection to come is already here, according to the pattern of chiastic causality, whereby all life, from the alpha of creation to the omega of resurrection, is sourced from the Son of Man who lived, died, and rose again in the center of history and says to His beloved, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, He who is (ὁ ὤν), and who was, and who is to come, the Pantocrator” (Rev. 1:8).

This was a very beautiful text. One of my favorite of yours I think. I'm sorry if this is not appropriate, but it read like St Ephrem or another Church Father: not a stagnant piece of reasoning, but full of (His) Life.

While reading it, I thought: "I must become Abraham/Peter, so I can become Isaac/James, so I can become Israel/John".

Awesome work Cormac.