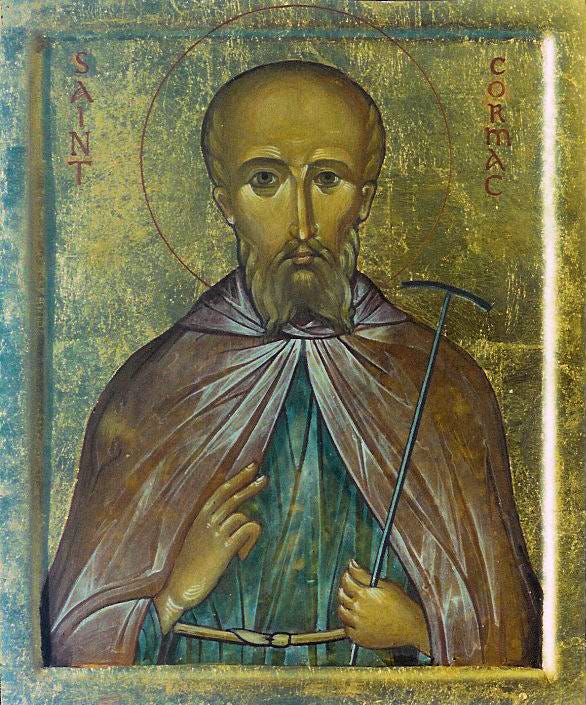

St. Cormac of the Sea, a holy failure

He strove for the margins but was exiled to the center. Commemorated June 21.

St. Cormac Ua Liatháin (“grandson of Liatháin”), also known as St. Cormac “of the Sea”, was a native of County Cork and lived in the sixth century. As a monastic in his adult life, he for a time joined the ranks of “white” martyrs that adorned the Irish people. Red martyrs were those who were killed for Christ; green martyrs were those who lived lives of ascetic virtue in their homeland. The white martyrs were those who of their own choosing renounced the lush green earth of Ireland to find salvation on a path of exile, which before Christian times had rather been a common penal sentence.

Most of what we know concerning St. Cormac comes from the magisterial Life of Columba by St. Adamnan. St. Columba was the most famous of white martyrs, sailing north from Ireland to found a monastery on the small island of Iona, in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. St. Adamnan was his greatest successor as abbot of Iona, living a century after him. He wrote that St. Cormac, “a holy man” and friend of St. Columba, “on no less than three occasions toiled in search of a desert hermitage in the ocean, but without finding one.” Once St. Columba prophesied to those with him on Iona, “Once again today, Cormac sets sail in search of a desert hermitage, from the district called Eirros domno which lies across the River Mod. But not even on this occasion will he find what he seeks, and for no other fault of his but that he has wrongly taken with him as companion on the voyage a monk of a devout abbot, who departed without the abbot’s permission.”1

Of a second and third attempt by St. Cormac to find a desert hermitage in the ocean, St. Adamnan writes as follows:

At another time Cormac, a soldier of Christ, to whom we have made some brief reference in the first book of this work, tried on a second occasion to search for a desert place in the ocean for a hermitage. After he had sailed out from land with full sails across the limitless ocean, Saint Columba during those days, while staying beyond the Spine of Britain [that is, while he was on embassy in eastern Scotland], gave this charge to King Brude in the presence of the vassal king of the Orcades [the Orkney Islands]: ‘Some of our community have lately sailed out in the hope of finding a desert place in the endless sea. If by chance after their long wanderings they come to the islands of the Orcades, give strict charge to this vassal king, whose hostages are in your power, that no harm should be done to them within his borders.’ Now the saint spoke like this because he already knew in the spirit that after some months this Cormac would come to the Orcades, as afterwards happened. And because of the holy man’s aforesaid charge, he was spared in the Orcades from impending death.

After the lapse of a few months, while the saint was living on the island of Iona, one day some men who were in conversation suddenly made mention of the same Cormac in his presence, saying, ‘It is still not known whether Cormac’s voyage was successful, or not.’ Hearing these words, the saint spoke as follows: ‘Cormac, of whom you are now speaking, will arrive today, and you will soon see him.’ And after about one hour had passed, strange to tell, behold, Cormac appeared unexpectedly and entered the oratory, while they all marvelled and gave thanks.

As we have included a brief mention of the blessed man’s prophecy concerning this Cormac’s second voyage, we must now devote some words to his similarly prophetic knowledge of the third.

When Cormac was toiling for the third time in the ocean, such were the perils that beset him that he came close to death. His ship had run from land for fourteen summer days and as many nights with full sails before the south wind, in a straight course towards the northern regions, and he seemed to have sailed beyond the limit of human venture and all hope of return. And so it came about that, after the tenth hour of this fourteenth day, there arose on all sides terrors, inspiring dread almost beyond endurance; for they were confronted by some repulsive and highly aggressive little creatures, never seen before that time, which swarmed over the sea and attacked with fearsome violence, striking at the keel and sides, stern and prow with such force, that it was thought that they could penetrate the hide that covered the ship. Those who were there told afterwards that they were about the size of frogs, with extremely troublesome stings, but they did not fly, but swam; and they attacked the blades of the oars. At the sight of them, together with the other monsters which this is not the time to describe, Cormac and the sailors who accompanied him, in great fear and alarm, prayed tearfully to God, who is a merciful and ready helper in distress.

At that same hour also our Saint Columba, although far distant in body, was yet present in spirit in the ship with Cormac. At that moment, therefore, he called the brothers together at the oratory by the ringing of the bell, and, going into the church, he spoke to them as they stood there the following words of prophecy in his accustomed manner: ‘Brothers, pray with all your power for Cormac, who has now sailed incautiously beyond the limit of human travel. He is now experiencing terrors of a monstrous and dreadful nature, never before seen and almost indescribable. We ought, therefore, in our minds to share the sufferings of our brother monks, placed as they are in unbearable peril, and pray to the Lord with them. For behold, Cormac, the tears streaming down his face, is praying fervently with his sailors to Christ: let us also help him with our prayers, that Christ, in pity for us, may turn round the south wind, which has blown these last fourteen days, to blow from the north. And may this north wind bring back Cormac’s ship out of its perils.’

After saying this, he knelt before the altar, and in a tearful voice prayed to the almighty power of God, which governs the winds and all things; and when he had prayed, he quickly rose, wiped away his tears and gave joyful thanks to God, saying, ‘Now, brothers, let us congratulate our dear ones for whom we are praying, because the Lord will turn round the south wind now to blow from the north and bring back our brother monks out of their perils; and it will return them to us here again.’ And at once, as he spoke, the south wind ceased and a north wind blew for many days afterwards; and Cormac’s ship was brought back to land, and Cormac came to Saint Columba; and by God’s favour they saw each other face to face, to the great wonder and delight of all.

St. Columba had great love and respect for St. Cormac, and when he had founded the monastery of Durrow, back in Ireland (Co. Offaly), he placed St. Cormac as its first abbot. But look where Durrow is on a map of Ireland:

Right smack dab in the middle — St. Columba placed this aspiring white martyr as far away from white martyrdom as humanly possible. Ha! Thus St. Cormac ended his journeys, filling his days with a fruitful pastoral life back in Ireland. Our last glimpse of him in the Life of Columba is in a party of great abbots visiting St. Columba on the isle of Hinba near Iona, a group which included St. Brendan of Clonfert, St. Comgall of Bangor, and St. Kenneth of Aghaboe. And so he kept good company.

Besides the pastoral life, however, in his old age he also found retreat at a hermitage he founded not too distant from Durrow, in the woods of Firceall beside the Silver River (also Co. Offaly). Today this is the town of Kilcormac (meaning “cell of Cormac”) which boasts of St. Cormac as their patron, and has preserved through the centuries his holy well, ever a place of pilgrimage and devotion.

Translations from the Life of Columba are by John Gregory, published in John Marsden, The Illustrated Life of Columba (Edinburgh: Floris Books, 1995).