The Beatitudes as octave and as Octoechos

A multivalent method for seeing the overly familiar with fresh eyes

I’m prepping to teach the kids in my Sunday school class about the Beatitudes. Yes, that’s right, the author of this Substack also teaches children Sunday school lessons. Don’t worry! I do not laden them with structural analyses that they have no use for and would only scare them. I promise you I have never used the word ogdoad with the children. It’s a small parish; there aren’t many kids (or many candidates for Sunday school teacher!), and among the kids there is a wide age range, from ages six to fifteen, give or take. I can’t say how well I’m doing from their perspective, but I know for me it has been a tremendous exercise taking the patterns of revelation I’ve learned in my life and finding them in the most basic expressions digestible for all ages. It’s like using my knowledge of a plant’s organism to isolate the seed and sow it in fresh soil. I’ve only been at it for about four months now, so I have no idea yet about the quality of my farming. For now I keep my hand on the plow, and I pray.

And I continue to study agriculture, as it were. Both farming crops and raising livestock. This inspection of the Beatitudes that I’m here about to undertake won’t be on a children’s level, but milk and meat come from the same animal. I’ve had cause to reflect, whenever I find myself studying some lofty philokalic Church father or other in preparation for teaching children, on how qualitatively different the Orthodox tradition of the East is from the Scholastic tradition of the West. In the West we may get our milk from a certain animal, but we grow our meat in a lab. What counts as advanced theological literature in the Western tradition is completely useless to a Sunday school teacher preparing a lesson on Holy Scripture for children. But in the Orthodox tradition — which in its approach to revelation positions beauty first instead of rationalist truth, as Timothy Patitsas explains it — the Church’s philokalic (“beauty-loving”) literature trains one in patterns that can be applied analogously on all levels of spiritual development. Milk and meat come from the same source. We all know that the Gospel is a pool shallow enough for toddlers to play safely in, as well as deep enough for elephants to bathe completely in, and the Church body animated by this Gospel should share the same qualities.

1. Octave

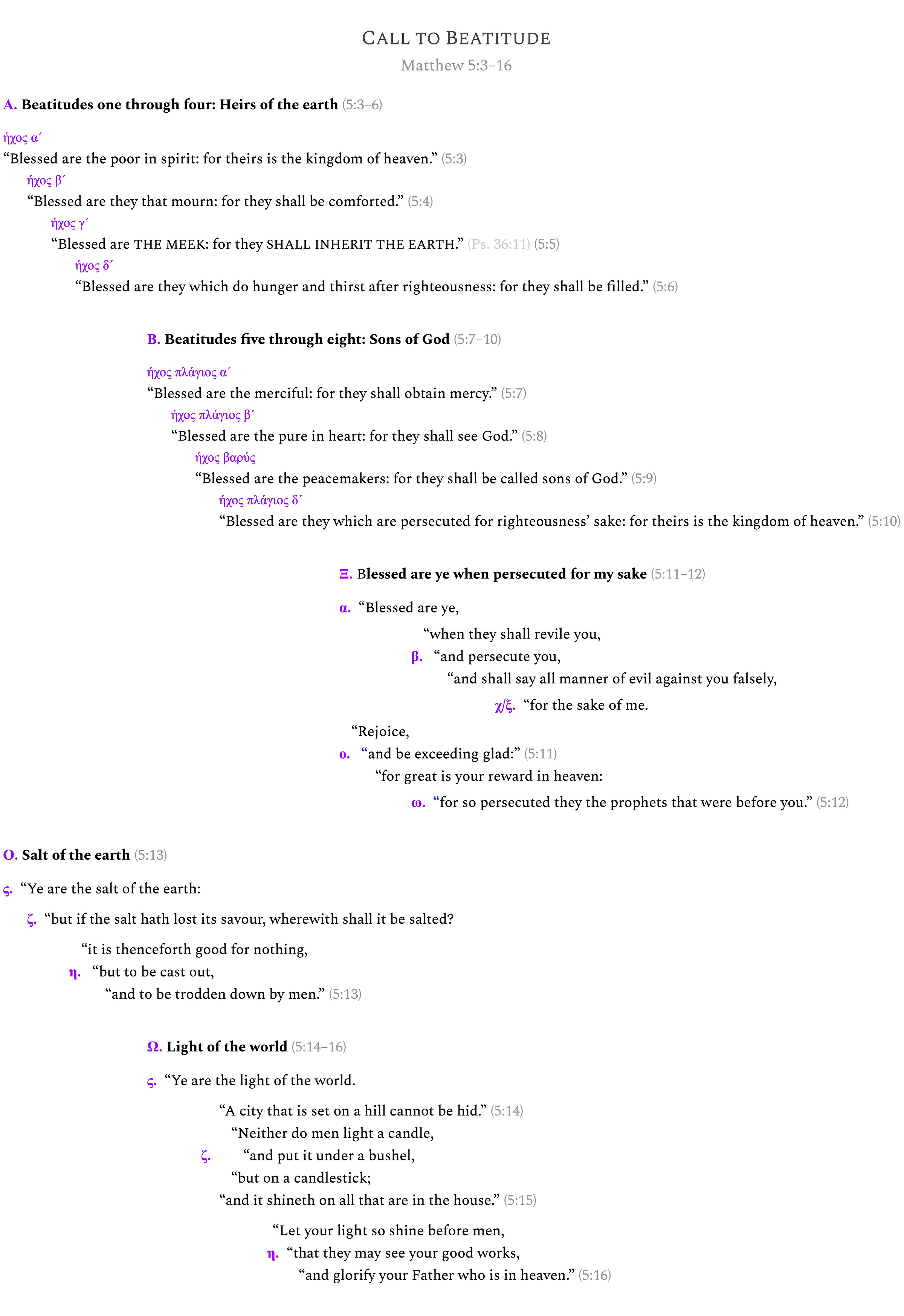

The Beatitudes in Matthew ch. 5 have an eightfold structure. Eight times Jesus says, “Blessed are the...” (Makarioi hoi...). Then a “Blessed are ye...” (Makarioi este...) punctuates the sequence; I’ll get to that later, but first let’s look at the eightness of it all. The octave is the shape of a Christian week, a seven-day sabbath cycle plus an eighth-day resurrection. As I’ve been exploring in this journal, the Christian week can be contemplated in two parts: the chiastic fivefold work week (which I symbolize as α–β–χ–ο–ω) and a weekend of triadic ascent (ς–ζ–η), prepared for on the sixth day, centered on the sabbath rest, and culminating on the octave, both the eighth day of the week and the first day of a new creation.

The fivefold work week forms a chiasmus here starting in poverty and ending in mercy. Poverty (α.) is sheer inferiority, and mercy (ω.) is kindness towards the inferior. So the chiasmus begins with the bestowal of kingship on the inferior and ends with becoming like the one who mercifully bestows kingship on the inferior — thereby obtaining mercy, i.e., thereby becoming the aspirational inferior on whom kingship is bestowed. Only the humble will be exalted. Only the merciful will be shown mercy. Such virtues fit the pattern of creation and judgment at the alpha and omega of the sequence, respectively. Creation bestows kingdom on those previously deprived of existence; those who are impoverished of spirit recognize that debt. In the judgment at creation’s end, moreover, mercy is what we seek most of all; mercy is what we need.

Then, in the next layer of such a sequence, typically beta symbolizes a differentiation, and omicron a reconciliation of what had been differentiated. Accordingly, those who mourn (β.) grieve the separation of what had been united — chiefly God and man, but soul and body, parent and child, and other such pairs are all molded thereafter — while those who hunger and thirst after righteousness (ο.) desire, bodily and spiritually, for that unity to be restored. Both mourning and hungering/thirsting are epithymetic activities, meanwhile; that is, they are functions of desire, the appetite of the soul.

The meekness at the center of this fivefold structure (χ.), however, represents thymic virtue. Thymos (anger) is the seat of repulsion in the soul, whereas epithymia (desire) is the seat of attraction in the soul. These two passions work in tandem like the two poles of a bar magnet, the magnetic vectors pushing out of one pole (thymos) and pulling into the other pole (epithymia). They both in equal measure can be perverted towards evil (as in cupidity and rage, respectively), or redirected towards virtue: for epithymia, the virtues of temperance and divine eros, and for thymos, the virtues of meekness and courage.

Meekness in English sounds like weakness, but it means freedom from anger; the one who is meek can never be controlled by his indignation. Mastering one’s anger is the ultimate strength and the necessary first step towards courageously providing a shelter of protection from danger for oneself and others. Indeed epithymia’s virtue of divine eros needs a shelter protecting it from being malformed into carnal eroticism. So you can think of thymos and epithymia as having this heaven and earth relationship whereby heaven (or the sky) provides for and protects the earth from which the fruit of love is born. And so at the center of this chiasmus of beatitude we have the thymically meek inheriting the earth, a reflection of the chiastic outer layer where the kingdom of heaven is bestowed on the epithymetically poor.

Earth is the same word as land, though, and this blessing should definitely also be thought of in biblical terms as inheriting the promised land. The centrality of meekness here thus reflects the meekness of Christ on the Cross, responding to the rage of His creatures with the submissive love of God the Father, known to Him and shared with Him from before all ages. By means of this sacrifice is the promised land gained. The pattern of the Beatitudes one through five thus tells the whole cosmic story from an objective perspective.

And then the subjective perspective is covered when we reach the triadic weekend, for which I use the Greek numerals ς, ζ, and η (6, 7, and 8) because they perform the function of (ς.) the sixth day, the day of preparation, the day on which Adam was created, the day on which Christ was crucified; (ζ.) the seventh day, the sabbath, the sanctifying day of rest, the Great Sabbath when Christ rested in the tomb; and (η.) the eighth day, the Lord’s day, the day of the Resurrection, the first day of a new creation, which has no evening. This transformative triad of ascent is participated in by each and every faithful member of the Church through the three stages of the spiritual life known by various terms, among them: purification, illumination, and perfection.

“Blessed are the pure in heart” (ς.) literally refers to purification; its reason for blessedness is the succeeding stage of illumination: “for they shall see God.” “Blessed are the peacemakers” (ζ.) signifies the sabbath rest enjoyed by those who see God in illumination; its reason for blessedness is the succeeding stage of perfection: “for they shall be called sons of God.” To be a son of God, Christ shows, is to be persecuted for righteousness’ sake (η.). Voluntarily to take on such suffering, to take upon oneself the sins of others, is the proper understanding of perfection. The scale is completed; as with two notes struck an octave apart, the reason for blessedness is the same as was given in the beginning — “for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

This use of inclusio suggests the close of a structure. The “Blessed are ye” that follows incorporates the octave into a yet larger structure that I won’t be able to discuss before I first consider an alternate arrangement of the eight.

2. Octoechos

As fruitful as I find the 5 + 3 pattern for contemplating eightfold sequences, I would be remiss not to explore also a different, but equally natural pattern of eight. Last week I mentioned the eight services of the day according to the Horologion. First of all there are Vespers, Compline, Midnight Office, and Matins, and secondly there are First, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Hours — two sets of four. But there’s a better example of this I wish to discuss. Last week I also introduced the Octoechos as a hymnal tracing the pattern of the eight-day Christian week in eight week-long iterations according to eight musical tones. The word Octoechos refers to that hymnal, but it also refers to the ancient musical system that the hymnal is based on. Here I mean to consider the pattern of this eightfold musical system, which is organized not as 5 + 3, but rather as 4 × 2.

The Octoechos first of all presents four kyrioi tones, or principal tones, which are musical scales in which melodies are composed. Then there are four variations on these tones called plagioi tones, or plagal tones, which shift and expand the ranges of the scales (the word plagal comes from Gregorian chant which in the Carolingian era adapted the Eastern Octoechos system for the Latin churches). The first four tones are numbered one through four (α΄ through δ΄ in Greek numerals), whereas the next four are known merely as their plagals, as in the plagal of the first tone or the plagal of the second tone — with the exception that there is no plagal of the third tone. That which is seventh in order, and is related to the third tone, is rather known as the grave tone, in Greek the varys tone, varys meaning grave as in “heavy”. Not unmeaningfully is this word denoting “heavy” translated as “grave”, as this is the tone seventh in order, the sabbath rest. So within the linear two-leveled parallel structure of the Octoechos, there is a nod to the sabbath sequence in the seventh position — before, that is, it snaps back into parallel structure with the plagal of the fourth tone being the eighth in order.

I’ve called this 4 × 2 pattern natural, and so it is. The form is found in heavenly nature when considering another facet of the Octoechos, which is its function as an eight-week liturgical cycle (an ancient practice predating the current hymnal several centuries). An eight-week cycle is two months. Symbolically, it’s two moons. A lunar cycle is 29 days (rounding down the fraction), which is (7 × 4) + 1. A sabbath week thus represents one quarter of the lunar cycle. The plus-one signifies the eighth day of the octave, such that a lunar cycle beginning on a Sunday would also end on a Sunday, traversing the interval from the first to the eighth in four iterations. Four weeks are symbolically one moon, so eight weeks are symbolically two moons. The meaning of two moons, meanwhile, is seen in the story of Jephthah’s daughter in Judges 11. Jephthah foolishly vows to sacrifice her, his only child. She consents to the sacrifice on the condition she be allowed to mourn her virginity for two months in the mountains. Two months is the time span from one new moon to a second new moon to a third new moon — three new moons, or in the case of Jephthah’s virginal daughter, three menstruations, three sheddings of blood. The daughters of Israel likewise went to mourn her annually for four days, it says at the end of the story. Veiled within four masculine days are three feminine nights, symbolizing three new moons, three sheddings of blood that propel the cycle of life.

So when one looks at the Beatitudes, as easily as a 5 + 3 octave structure can be seen in them, so can a parallel 4 × 2 pattern be seen. The first and the fifth Beatitudes, poverty and mercy, which I compared as the alpha and omega of a chiastic structure, here correspond as the heads — the first tone (ήχος α΄) and the plagal of the first tone (ήχος πλάγιος α΄) — of two parallel groups of four. The second set of four, the plagals, headed by the omega, accordingly occur as eschatological escalations of the four principal Beatitudes headed by the alpha. I set out the parallels below, interspersed with the phases of the moon to illustrate how this linear eight-week structure corresponds with cyclical time after a fashion both chiastic, in the fivefold structure of a lunar cycle, and triadic, in the linear progression of the three new moons.

The second tone (ήχος β΄) says, “Blessed are they that mourn,” whereas the tears from such mourning provide a necessary cleansing agent to achieve the purity of heart pronounced blessed in the plagal of the second tone (ήχος πλάγιος β΄). Likewise the sensible feeling of comfort for having been “drawn near to” (the etymological sense of the Greek word for “comforted” here) is in purity of heart augmented as a most exalted sensation, the very vision of God.

Then in the next step, the freedom from anger blessed in the third tone (ήχος γ΄) is matched by the making of peace in the grave tone (ήχος βαρύς). In doing so, one goes from becoming the heir of land to the heir of God, for a “son” of God is an heir of God. (Translations that say “children of God” when, as here, the words are actually “sons of God” obscure the context of inheritance law amongst the original audiences of the text; whereas, in context, not all children are heirs, sons specifically are. Followers of Fr. Stephen De Young will likely have heard him make this distinction multiple times.)

Finally, one’s hunger and thirst for righteousness in the fourth tone (ήχος δ΄) turns into willingness to be persecuted for the same cause in the plagal of the fourth tone (ήχος πλάγιος δ΄). Filling the appetite for righteousness then amounts eschatologically to the very kingdom of heaven; righteousness is heaven’s reign.

Hence the serpent of polyvalence comes for the Beatitudes. Contemplating them as two parallel lines of four, the second eschatologically augmenting the first, can be just as productive as my typical 5 + 3 octave structure. Seeing them in two parts, moreover, will be necessary for what comes next: viewing the Beatitudes in a wider structural context.

3. Ksiasmus

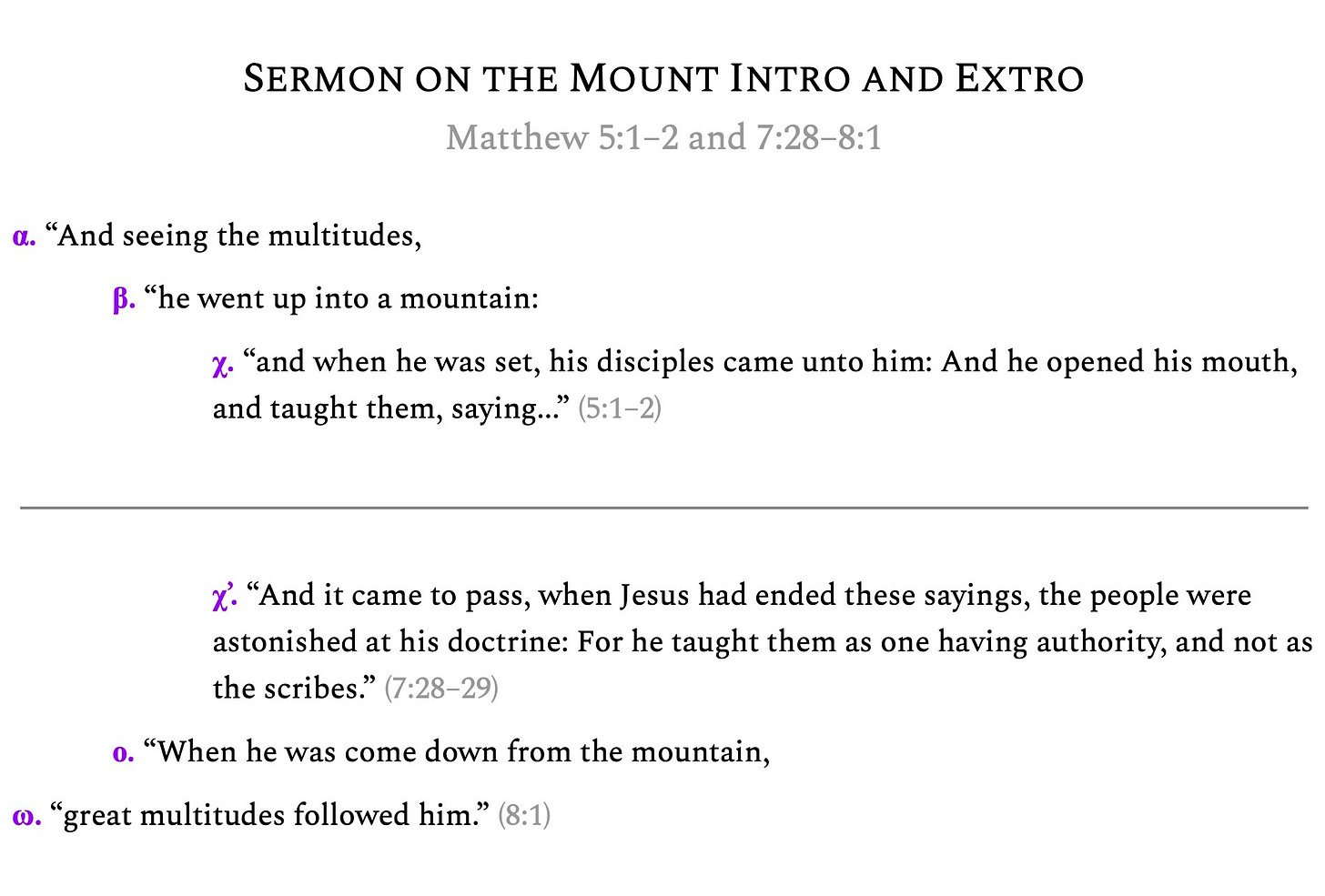

The Beatitudes comprise the opening lines of the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of St. Matthew, a very discrete formal structure in a very discretely structured Gospel. For example, the Sermon on the Mount is introduced and concluded with phrases chiastically reflecting each other. It all begins with an ascent and ends with a descent, like so:

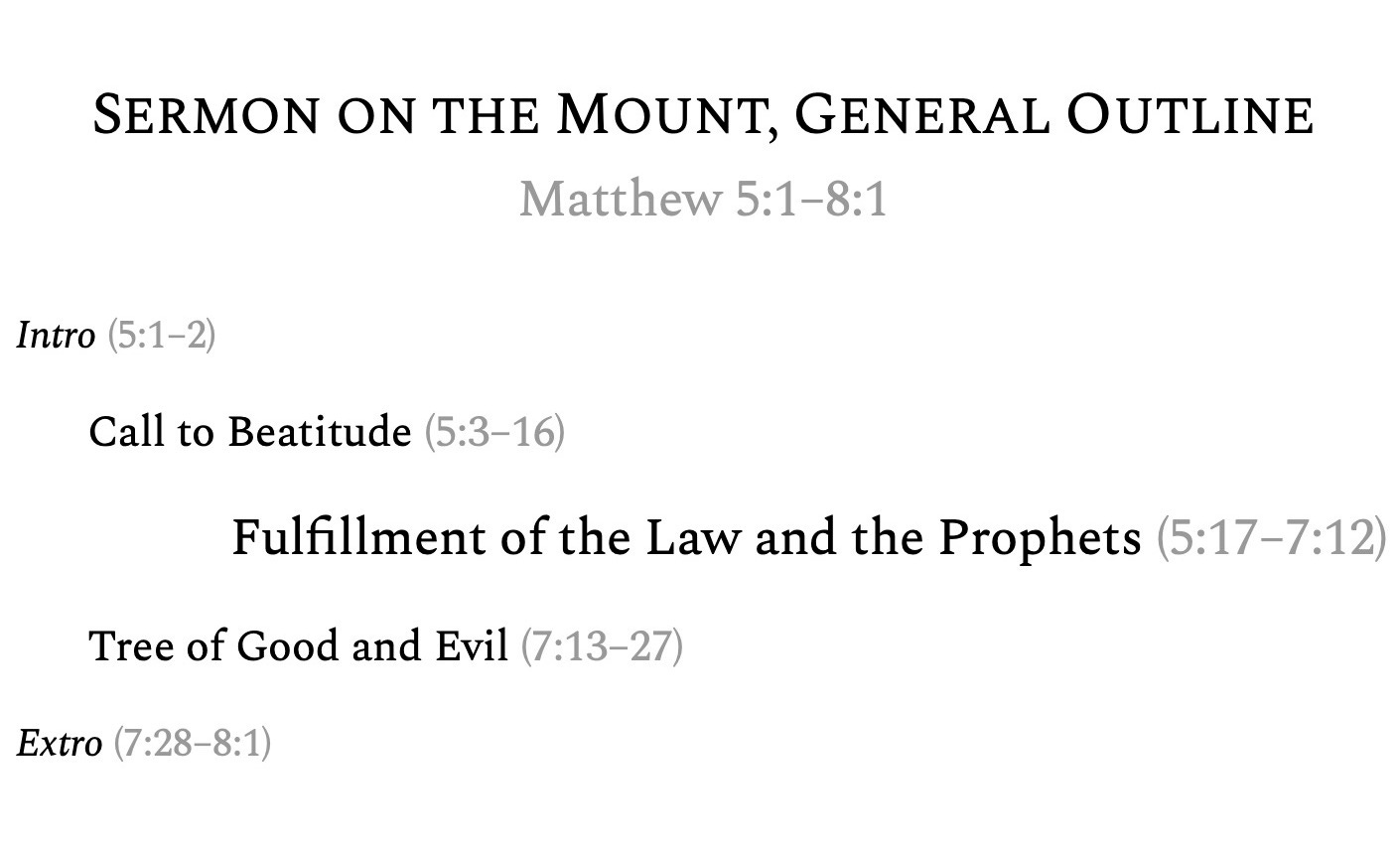

Another use of inclusio bookends a greater chunk of text within the Sermon. It comes in the form of mentioning the Law and the Prophets, beginning in 5:17 and finishing in 7:12. That sets apart 5:3–16 as an opening section and 7:13–27 as a concluding section. A thumbnail general outline of this chiastic mountain of a sermon thus looks like this:

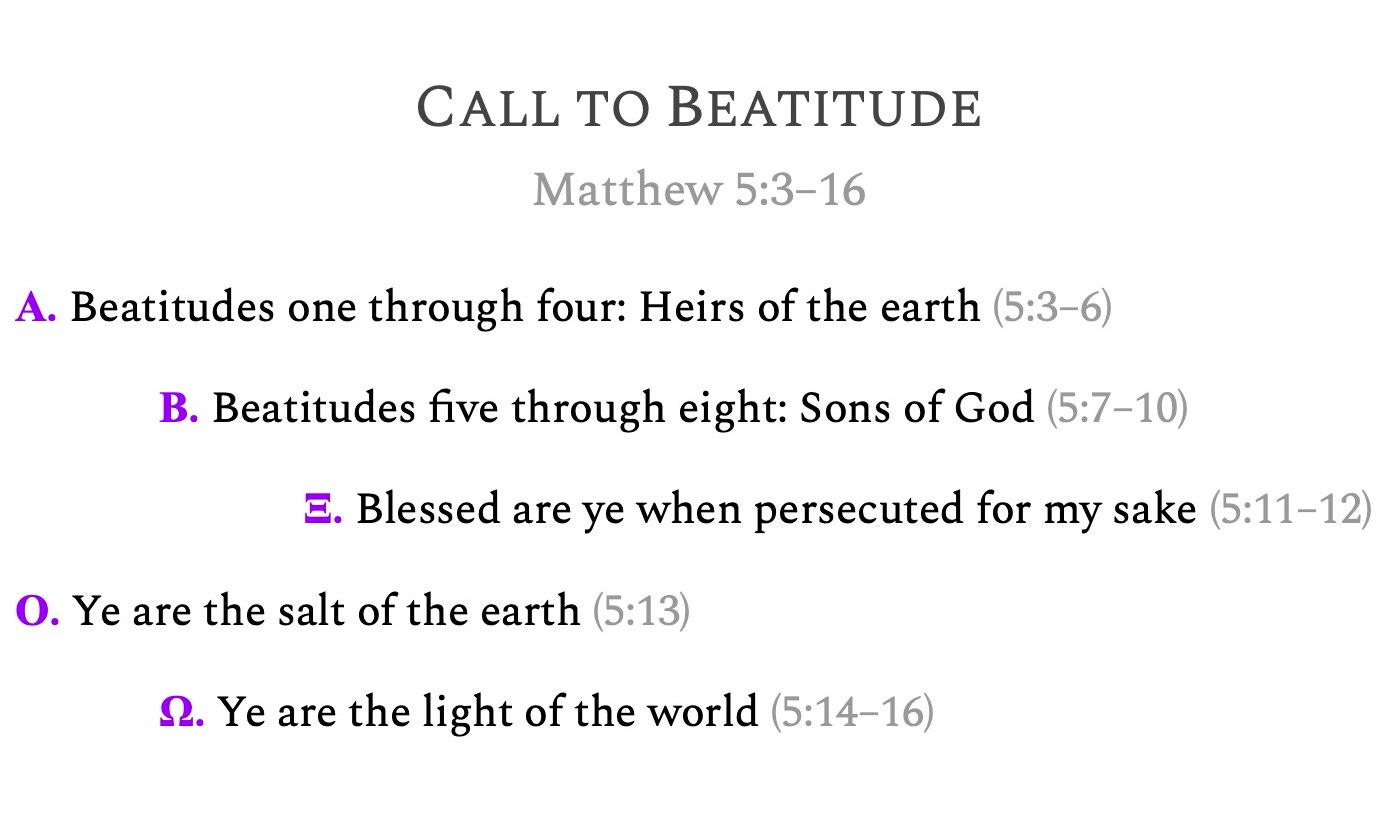

So a structural contemplation of the Beatitudes in the Gospel of St. Matthew would not be complete without at the very least considering how they correspond with the “salt of the earth” and “light of the world” passages that follow in 5:13–16. Here finally is where we find the structural purpose of the “Blessed are ye” verses (5:11–12) — they provide the ksiastic center on which the passage hinges.

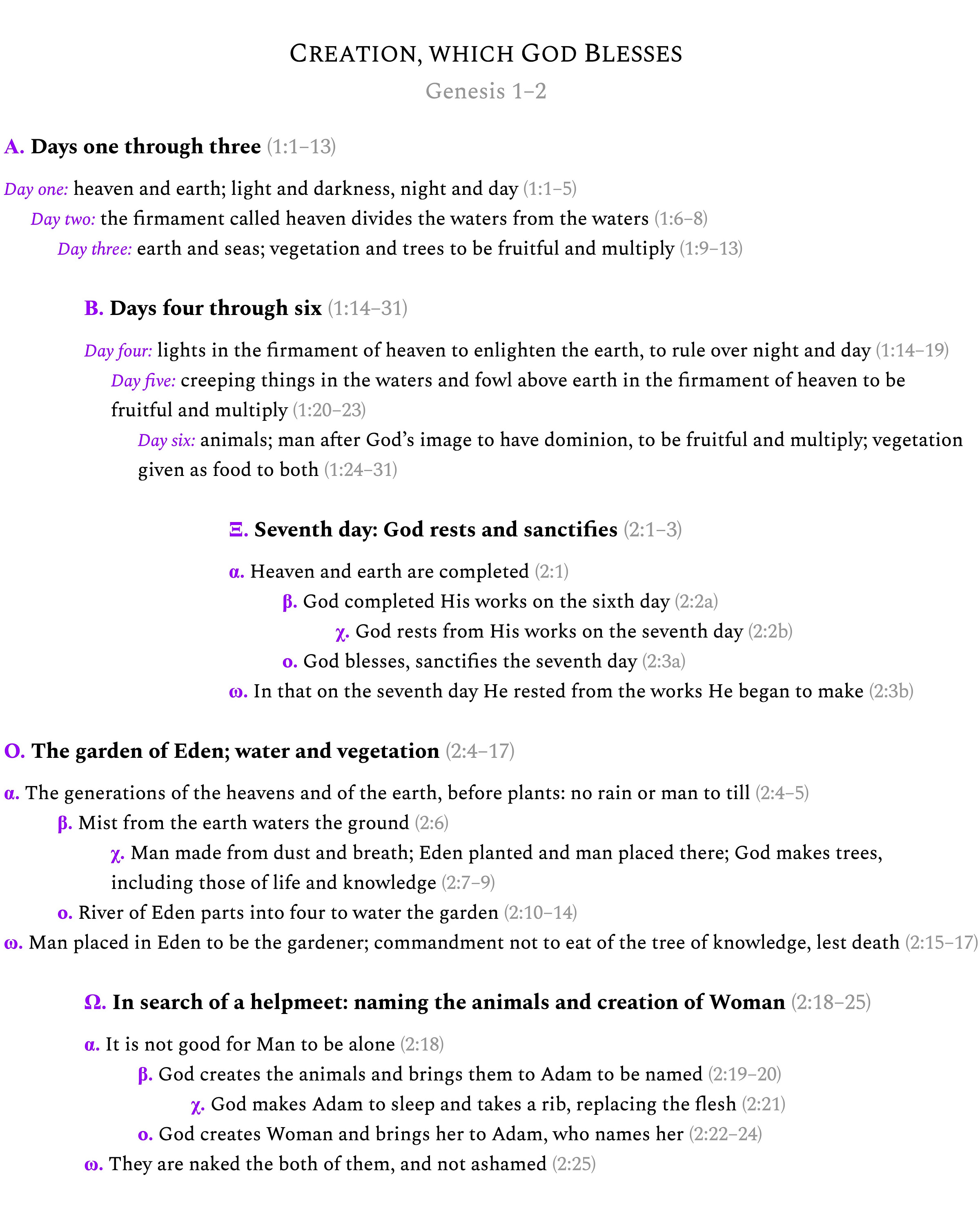

It might seem strange that a unified structure like the Beatitudes would be broken in parallel halves like this, with an extra element in very similar form used as a center binding the two halves to two other passsages, themselves seemingly two peas in a singular pod. Well, this structure definitely has precedent, and it’s no obscure pericope. The first book of the Bible for which I did a chiastic outline was Matthew; the second one was Genesis. Having seen how clearly St. Matthew’s Gospel is arranged helped me see the following structure in the opening chapters of Genesis (see this outline in context here):

The seventh day described in Genesis 2:1–3, though explicitly different from the other days, seems like it yet should not be numbered apart from them. I mean, it’s literally numbered among them. But its content sets it apart; in symbolizing the life-giving death of Christ, it forms a pentadic center. Likewise the Hexaemeron is a unit to be contemplated as a singular structure, as I show in “The Cosmic Chiasmus”. But I also show in that article how the parallel threefold structure is also plainly visible, as God in the first three days sets out to give form to the world, then in the second three days fills the void of the places He made with creatures. This relationship is then reflected in the parallel structures of the creation story in Genesis 2, in how at first paradise is created for Adam as a place of potential, and then it becomes a place of activity in the multiplication of gender.

The opening structure of the Sermon on the Mount follows the same formula, as if to characterize the establishment of the virtues in a fallen world as a re-genesis. To begin, though, the Beatitudes are an octave unit. Whereas the Hexaemeron depicts the relative perfection of six — relative to creation, that is — the Beatitudes show the absolute Christ-like perfection of eight. Nonetheless the Beatitudes, like the Hexaemeron, can be read in two parallel layers, the two moons of the Octoechos. Then we have the passage that appears to be an expansion on the Beatitude idea: “Blessed are ye, when they shall revile you, and persecute you, and say all manner of evil against you falsely, for the sake of me. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets that were before you” (Matt. 5:11–12). Like the sabbath rest on the seventh day, these verses portend the death of Christ and form a ksiastic center binding what came before with what comes after.

Let’s just go ahead, then, and look at the full text:

The central passage, the “Blessed are ye” (Ξ.), is internally both chiastic and ksiastic. Formally, in that the beta and the omicron are both triadic while the alpha and the omega are single lines, it looks chiastic. But if you think about the content, the shape appears ksiastic, with alpha and omicron pairing off in happiness (makarioi can be translated as blessed or happy) and beta and omega pairing off in persecution. It all hinges on “for the sake of me” (eneken emou) — enduring persecution is only meaningful and joy-giving if it’s for the sake of Christ.

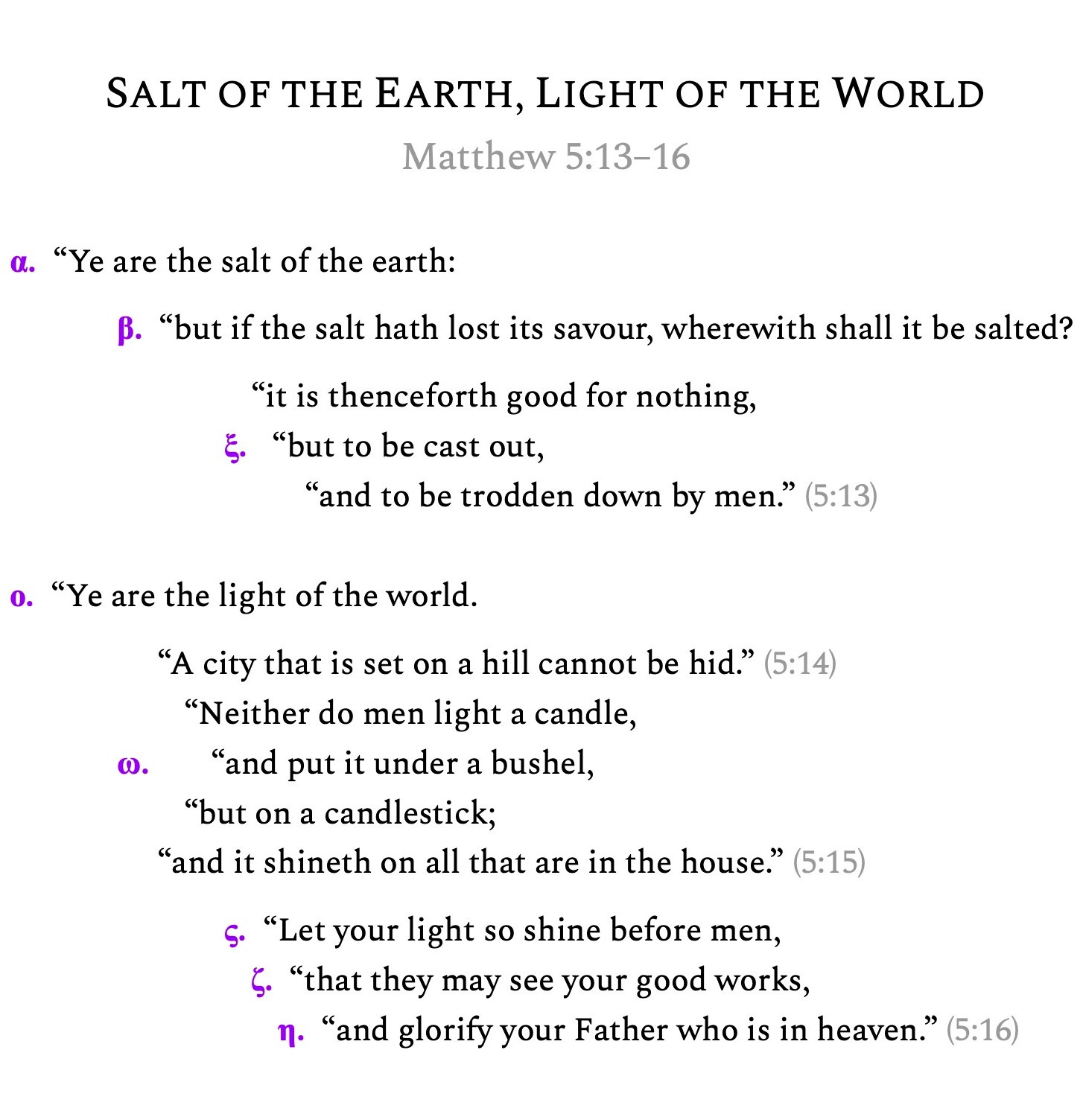

That brings us to the salt of the earth and the light of the world. Salt is meant here as more than mere seasoning, more than mere ornament. Salt is a preserving agent, extending the life of that which is seasoned. The second-person plural “ye” being addressed are of continuous identity with the “ye” of the central blessing: they are those being persecuted for the sake of Christ. They’re the salt of the earth because that’s what Christ is. He preserves that which is subject to spoiling; He gives life to that which is subject to corruption and death. And there is no higher source of life than that. Salt which has lost its savor can’t be salted, just as those who betray Christ have cut themselves off from life. This insight, as I’ve marked it here, forms the zeta (ζ.) to the stigma (ς.) of being the salt of the earth. The perfection of this failing (or the perfection of the awareness thereof) is achieved in the eta (η.): being cast out and trodden down by men as good for nothing else.

But it remains the case that being the salt of the earth is a good thing, and the extension of existence it grants to the earth receives its eschatological escalation in the transference to light. The world exists in light, so to be the light of the world is to be phenomenologically like the source of all created things. The city on a hill is an image of eschatological paradise, the heavenly Jerusalem, and its chiastic juxtaposition with a candle shining within a house refers symbolically to the kingdom of heaven within the human being. This should be made known to others, this little triad concludes, not to the glory of the human being, but to the glory of God the Father.

All together, the “salt of the earth” verse plays the omicron role (Ο.) of the ksiastic structure for the way the followers of Christ extend the life of the world in the era of the Church (until, that is, they lose their savor!). It corresponds to the first half of the Beatitudes (Α.) in its relation to the earth. The “light of the world” verses, on the other hand, play the omega role (Ω.) for their apocalyptic, that is to say, revelatory aspect. As the second half of the Beatitudes (Β.) proclaims that the pure in heart shall see God and that peacemakers shall be called sons of God, so do these latter verses depict followers of Christ shining with a light of good works that causes the men who see it to glorify God the heavenly Father. This is in fact the culmination and final purpose of the Beatitudes: that we participate so actively in the glorification of God. No less than this is the great reward in heaven promised to those persecuted for Christ.

The symmetry of this whole pericope is so complete, I believe, that, even as the Beatitudes can fruitfully be contemplated as an octave, so too can the couplet of the salt of the earth and light of the world. For starters, the two opening lines form obvious parallels that can be thought of ksiastically as alpha (α.) and omicron (ο.).

Then the salt losing its savor presents an image of fall and exile typical of beta in its negative mode (β.). The city on the hill that cannot be hid and the candlelight that shines on all in the house stand in for the eschatological imagery appropriate to omega (ω.). The triadic central ksi (ξ.) describes the curse on bad salt that Christ was willing to undergo for our sake by way of His Passion. Indeed, wherewith shall salt that hath lost its savour be salted? With the mystery of the Cross. It is common for pentads to have a triadic center as a reflection of the transformative ascent that octaves wear as a crown. Here we have both, a triad at pentad’s center and a triad as octave’s crown. Your light shines (ς.), such that men see it in your beautiful works (ζ.), and glorify your Father who is in heaven (η.). Hence are all the Beatitudes crowned with light — the virtuous works of men mystically, incomprehensibly, beyond mercifully being identified with the glory of God.

Ευχαριστώ Cormac! This was a marvel-ous read!

What practical example might you use to explain the ksiasmus and its presence in the fabric of creation to a Sunday school student? Asking for myself, hoping to be numbered amongst them virtually in so doing