The Gospel of Mark takes the sabbath super literally

An approach to the octave shape used also in Bright Week

I have seen attempts to outline the Gospel according to St. Mark using a thoroughly chiastic pattern from beginning to end — wherever one identifies the ending to be! (Scholarship has turned up a bit of controversy in that regard.) But I have never found that approach to yield a satisfying account of the Gospel’s contents. Matthew I could see was clearly chiastic. John, too, I saw as a pentad-based chiasm, and I was not alone in doing so. Acts was the same pattern. But what of Mark? What of Luke? The pattern didn’t seem to fit these books. When you’re looking at these things, you never want to impose a pattern on something that isn’t there. That’s like reading your own passions into the words of the Lord. The point is to reshape your vision according to the Holy Scriptures, not the other way around. I needed another lens to see the body of Mark’s text. Once I learned the octave from the Psalter, I tried it on Mark and felt I had found what I was looking for. There’s a strange catch, though.

The sabbath isn’t there. There’s no “Part 7”. The ending of Part 6 abuts directly with the beginning of Part 8. It’s like the Evangelist himself takes a sabbath rest from writing. I wouldn’t at all feel comfortable going with this model if the text itself didn’t make the structural lacuna as literal as it possibly could. It also helps that the liturgical pattern of Bright Week does exactly the same thing. Let’s look first at the Gospel.

With Mark, it’s best to start at the end. There’s a clear break between the accounts of Jesus’s ministry ending with chapter 13 and the Passion narrative beginning with chapter 14. As with the other Gospels, the Passion is a chiastically composed set piece (I won’t cover it here, but maybe in a future post); it carries through chapter 15 and concludes there. The final scene is set temporally with the words “And now when the evening was come, because it was the preparation, that is, the day before the sabbath...” (15:42). Joseph of Arimathea acquires Christ’s body from Pilate and buries it in a sepulcher; the Myrrhbearing Women behold the burial. Then chapter 16 opens with the tag, “And when the sabbath was past” (16:1). The space between chapters 15 and 16 is literally the sabbath, and there is literally no text there.

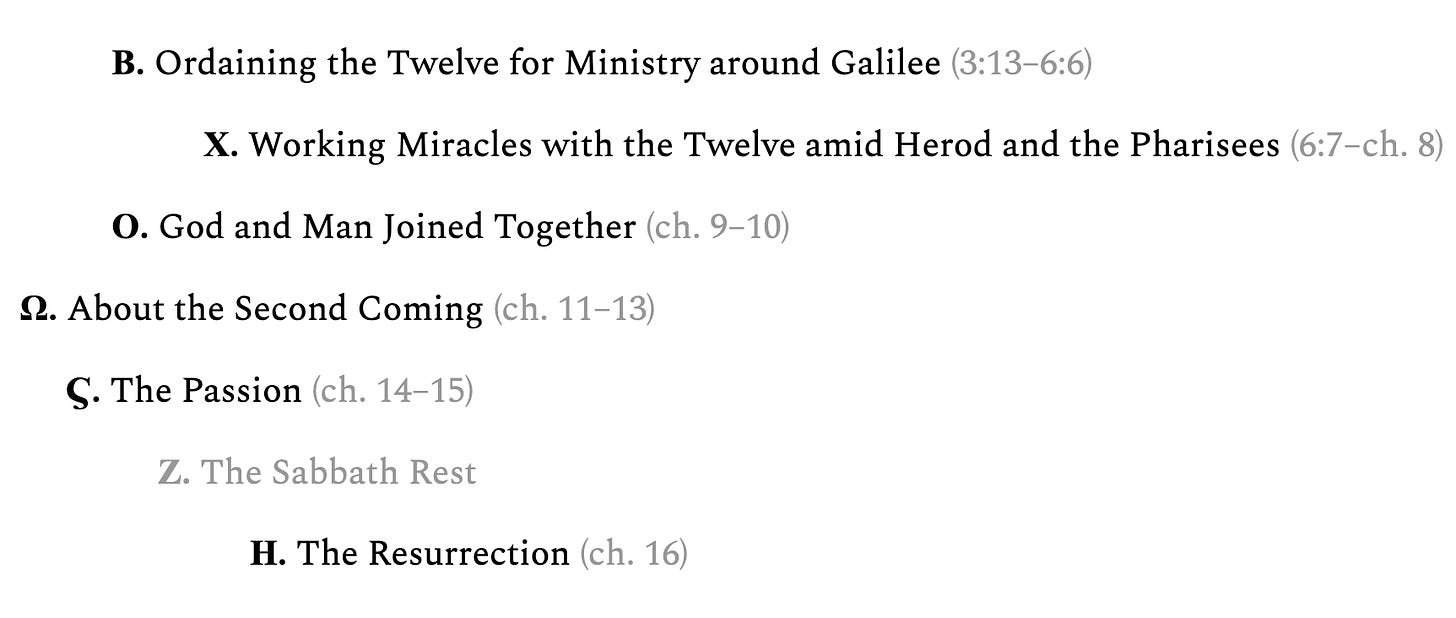

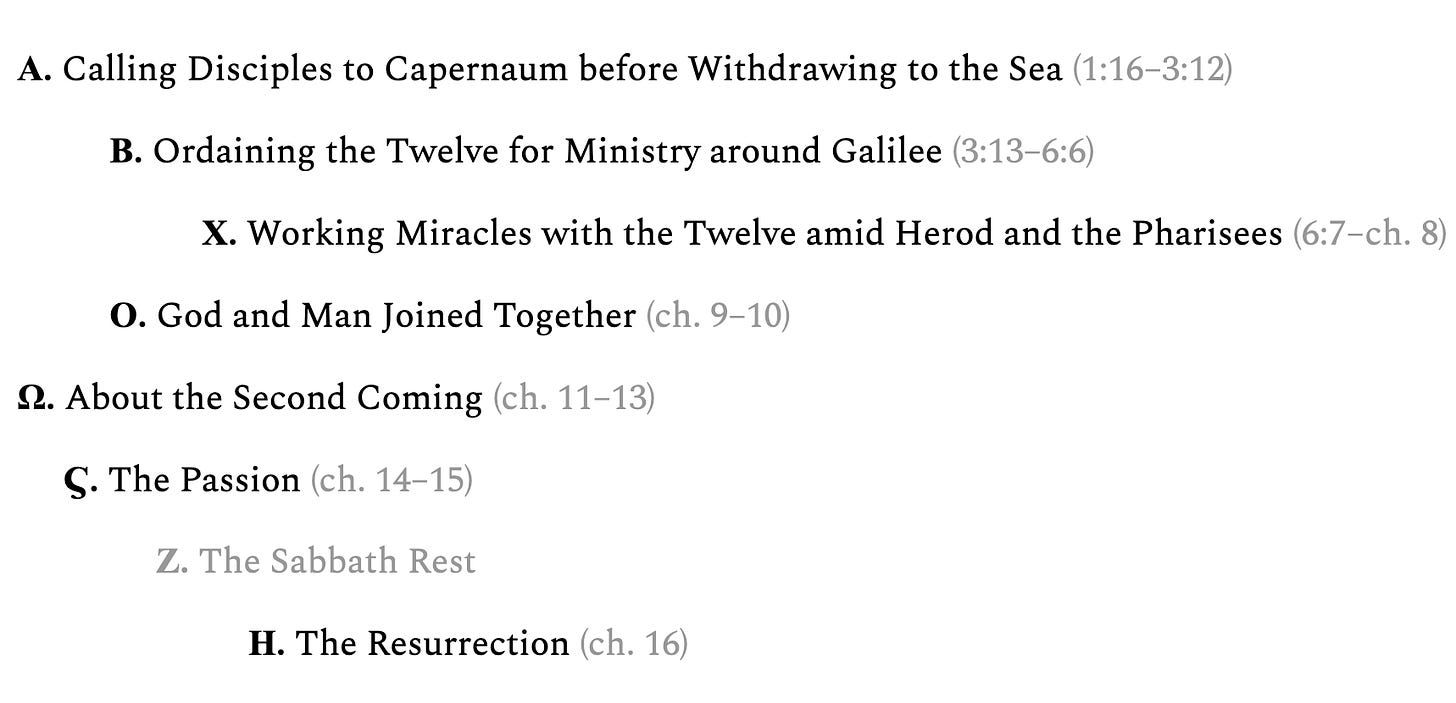

So if we set aside the Passion and Resurrection narratives in chapters 14 through 16, what does the rest look like? I don’t know if anyone else has thought to look for a chiastic structure between chapters 1 through 13, instead of 1 through 16, but that’s the approach I find to be successful. The results are pentadic. Again, working backwards, we first of all see that the Entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday takes place at the beginning of chapter 11, so all the text through the Apocalypse Sermon on the Mount Olives concluding chapter 13 consists of teachings of Christ during Holy Week before the Passion. I’ve mapped the text out as follows on my website:

As you can perhaps see (by way of the italic headings), this section of text could possibly be seen as a pentad, but I think the final three parts are best understood as part of a fractal triad. Either way, the text forms a unit focused on the Second Coming, as the Entry into Jerusalem already typifies the Second Coming by means of the First. This is the archetypal stuff we are accustomed to seeing in the omega-section of a chiastic pentad. Hence the back half of a would-be octave is already in place, with the first ten chapters remaining to fill in the front half:

Before Christ could enter Jerusalem He had to journey there, and we find in the preceding two chapters narrative relating just that. In the outline below, you’ll see in the italic headings mentions of geographic markers that plot out a pentadic sequence conforming to the cosmic chiasmus. Predictions of the coming Passion and Resurrection mark the beginning and end of the structure.

It ends (ω.) “on the way up to Jerusalem,” typologically the heavenly Jerusalem, hence worthy of the omega-symbolism. It all ends with departure from Jericho, the low city by the Dead Sea standing in for the lowly fallen version of this world to which we all will bid adieu. Before that, we are just (ο.) “on the way,” even as the Church is on “The Way” in the interval between Christ sowing salvation in the earth and the harvest of the final judgment. Typically for omicron-symbolism, this is a time for growth and fruitfulness in the virtues; hence, the topic of riches and what to do with them is on point. Previous to that, we found ourselves (χ.) “at the borders of Judea by the far side of Jordan,” a crossroads and a threshold worthy of chi-symbolism. The topic is divorce, an image of death, the separation of soul and body, but put in the terms of marriage, the separation of husband and wife. All of this epitomizes what you would expect in the chiastic center of the omicron-section of a larger structure. The passage peaks with Christ bidding little children come unto Him — children being the products of marriage, not divorce, and symbols of resurrection, of life after death. Before this we were (β.) at Capernaum in Galilee, among Judeans who kept the Torah, but in a place removed from Judea and the Holy City, an exilic distinction appropriate for beta-symbolism relative to the context of this section. Here Christ instructs the disciples in what to cut off (causes for offenses) and what not to cut off (children, those working miracles in Christ’s name). He is teaching how to sacrifice oneself for love of others, an exile from selfishness that works both locally as the beta-passage of this structure, and more generally as part of an omicron-style focus on fruitfulness in virtue.

This backwards-tracing pattern would lead us to expect next a passage of alpha-typology that perhaps parallels chiastically the Passion and Resurrection prediction and healing of a blind man that occurs at the end of chapter 10. Indeed that’s what we find. Whereas at the end of chapter 10, we’re on the way to Jerusalem and departing Jericho, at the beginning of chapter 9, we’re (α.) on a high, paradise-like mountain (not in this Gospel identified as Mt. Tabor) for the exceedingly bright white light of the Transfiguration. Though Jesus is a man, He shines with a light from beyond all creation, and the God-seers Moses and Elijah appear, talking with Him. Mark’s is the Gospel that opens by identifying Jesus as the Messiah and the Son of God (two royal titles), the Gospel that through many displays of miracles recounted in the first eight chapters consistently establishes Jesus’s authority as identical to God’s. In the Transfiguration is revealed how, then, as the central passage of this section might word it, God hath made twain one flesh. God and man are one in Christ, a type of marriage the children of which are virtues and light. We have our omicron-section.

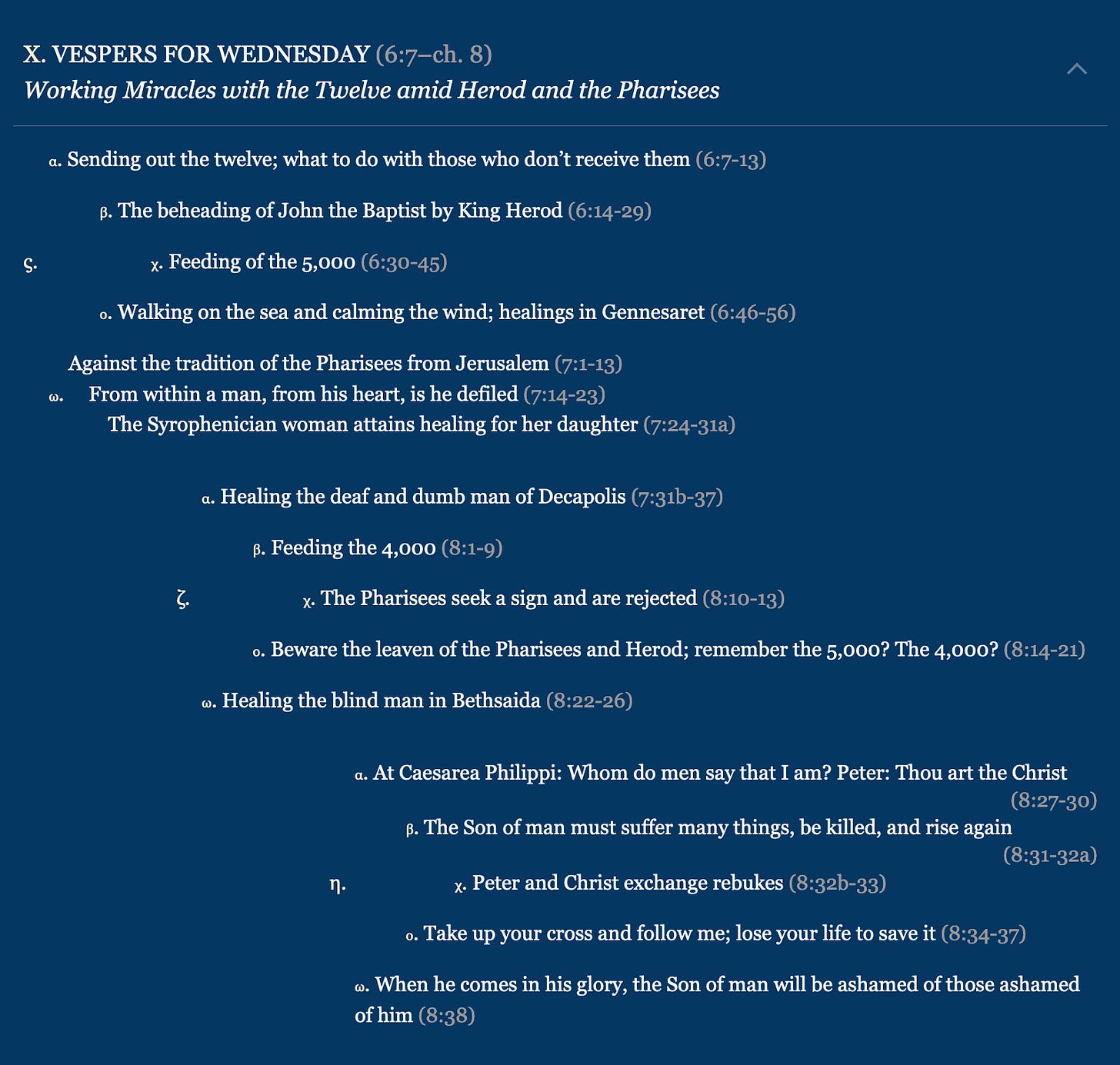

We are now left with the first eight chapters to fill in the first three parts of the octave. This make sense generally, as a turning point is commonly recognized in the eighth chapter, at which the Gospel’s emphasis on miraculous displays of authority gives way to more emphasis on the kinds of teachings we’ve seen in the omicron-section (about virtuous living) and in the omega-section (about the end times). Chapter eight concludes with what feels like the peak of an ascent: the scene at Caesarea Philippi where Peter confesses Jesus is the Messiah but rejects the Passion prediction and is rebuked. The twelve verses (8:27–38) form a clear instance of the fivefold cosmic chiasmus pattern, as charted and labeled in the bottom third of this section’s outline:

Looking back before Caesarea Philippi, starting with the cosmic image of the sending out of the Twelve, I see a triadic ascent of pentads, decreasing in size as they go, a typical shape for the center of chiastic structures. It’s like the tabernacle pattern in the center of the four camps of Israel: courtyard, Holy Place, and Holy of Holies. This shape occurs in the center of the Pentateuch, with Leviticus, and in the center of the Gospel according to Matthew, with the parables of the kingdom of heaven. A chiasmus is a round shape, so putting a threefold ascent in the middle is like an onion dome rising to a point above itself.

Content-wise, we witness in this section God emptying Himself out in His creation, a kind of divine image of a life-giving death. It’s in the sending out of the Twelve like light into darkness; in the martyrdom of John the Baptist, embodiment of the Law and the Prophets, at the hands of the hedonistic rulers of this world (a conspicuously placed flashback passage); and, centrally to the first pentad, in the eucharistic feeding of the five thousand. In the second pentad, the feeding of thousands is de-centered in favor of focusing on our reactions to the feeding, whether we can see its purpose or not, whether our senses, the senses not just of our bodies but of our minds, are opened to what God is communicating. So the first pentad traces the pattern of purification of the passions, as in the omicron-passage when human nature in the Person of Christ walks on the sea and calms a storm, and the second pentad follows with illumination. Perfection comes in the final pentad with the chief of the Apostles confessing Jesus as the Christ and being bent forcefully towards the seemingly impossible meaning of this identity — towards “the things of God,” towards self-denial, passion, and resurrection.

From the invocation of Herod’s tyranny to the mad unbelief of the Pharisees, conflict brought on by the powerful adversaries of Jesus forms the context of all His life-giving miracles in this section. Hence we have the chiastic center of the Gospel, betokening Christ’s life-giving sacrifice in the midst of all creation.

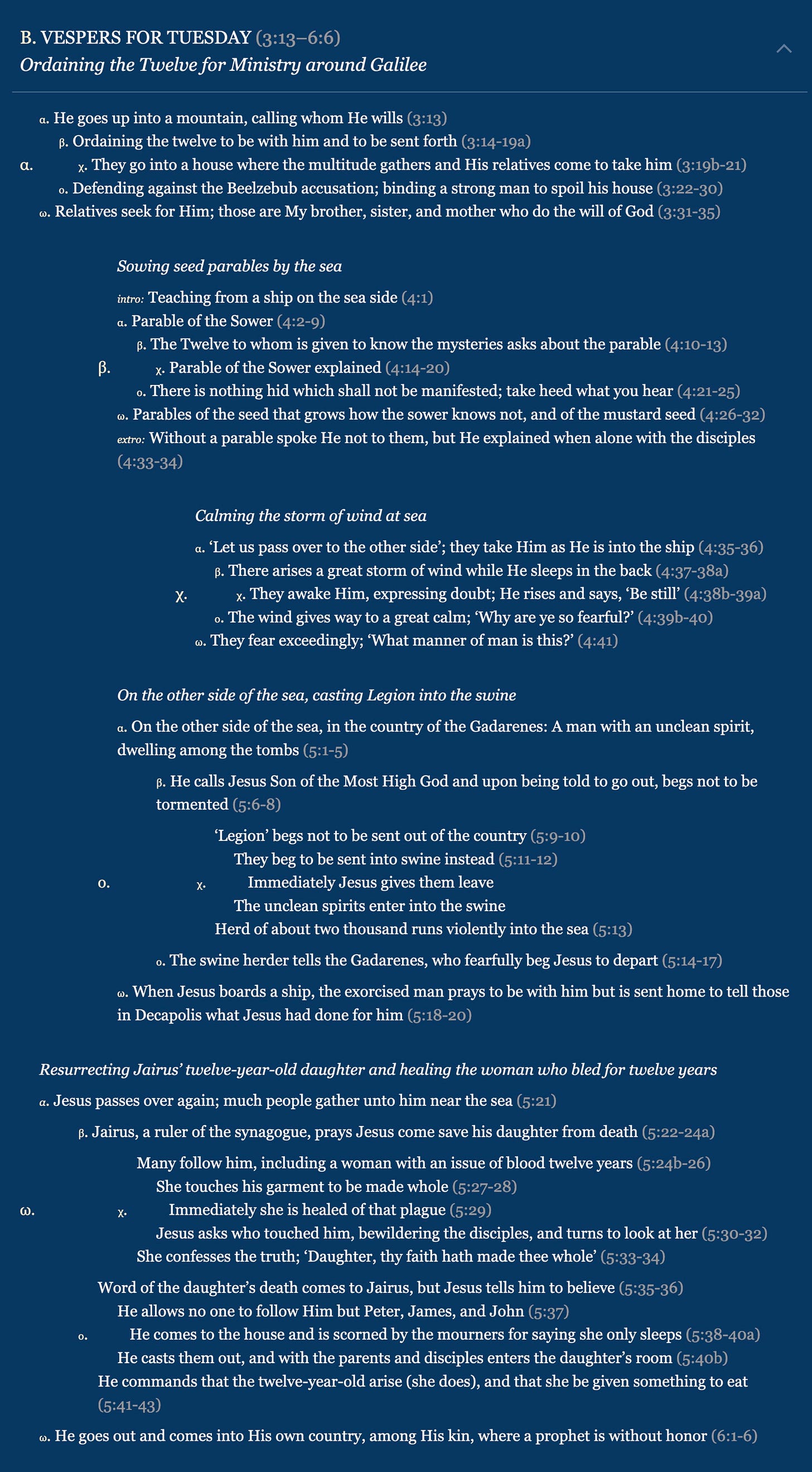

As we continue backwards, it’s clear to see what at least the next four pericopes would be, as indicated by the italic headings in the next outline. The geography forms a clear chiastic pattern around (χ.) the Sea of Galilee, in which Christ awakens from sleep to calm a great storm — symbolic of Christ’s passing through hades and saying to the chaos of death, “Be still.” Parables (β.) are taught on the near side of this journey, and, in the country of Gadarenes (ο.), casting a legion of demons into a porcine abyss occurs on the far side. The symbolically and chiastically entwined stories of healing the woman with a twelve-year issue of blood and resurrecting Jairus’s dead twelve-year old daughter (ω.) conclude the cycle of this part of the Gospel typologically even as they contextually conclude cycles of feminine death.

As with Part Ο when we were left to identify the Transfiguration on a high mountain as the local alpha-section, here in Part Β we find for an alpha-section this sequence of events from 3:13–35 starting with Jesus ascending a mountain, calling his disciples after Him, and ordaining the Twelve. Identifying this chiasmus, in this place in the Gospel, establishes a host of fractal parallels: the Twelve ordained men corresponding chiastically with the twelve-themed women at the end of the section; as mentioned, the parallel between the Twelve being called up a mountain here and the more exclusive trio being called up the high mountain for the Transfiguration in the chiastically corresponding part of the Gospel; and the further parallel of the sending out of the Twelve that initiates the chiastically central part of the Gospel. Indeed, the extension of this pattern will help us identify the remaining part of the structure. Here’s what we have so far:

Looking at the remaining text to be mapped, 1:1 through 3:12, I don’t see one consistent internal structure but two, divided by the beginning of Jesus’s ministry, the suggestion being that there is an introductory passage before the initiation of the octave pattern. Here is where I see the alpha-part of the Gospel beginning; as with the succeeding parts, it entails the calling of disciples:

And as if providing a map for the structure of the Gospel, the part itself is shaped as an octave highlighting the meaning of the sabbath. Here Jesus is alive on the sabbath (notably in 2:23–3:6), and so the evangelist doesn’t leave that section blank but writes what Jesus teaches about the meaning of the sabbath. This lesson is necessary if one is to understand the ultimate sabbath of the Gospel, when Christ lies dormant and the evangelist falls silent.

This meaning is also indicated by the center of the octave’s chiasmus (χ.), the healing of Simon’s mother-in-law. First of all, the disciple is identified not as Peter but with his pre-Christian name, Simon. Symbolically, Simon’s wife is the fallen world of corruption to which he is yoked. The mother of this wife is the death that begets her. This death Jesus heals from fever, and it immediately gets up to serve. Jesus makes a servant of death. Under the influence of Jesus, death becomes a minister unto life, both for Himself and for His disciples. So we have here in the center a symbol of the resurrection leading us to knowledge of the sabbath rest.

This center is chiastically framed by references to Capernaum (“village of comfort”). Firstly (α.), in a triadic sequence that follows Jesus from “by the Sea of Galilee”, to “a little further hence”, and finally to a synagogue in Capernaum on the sabbath, Christ calls Simon, Andrew, James, and John, creating the inner circle of discipleship around Him like the four heads of the river from paradise. (As with the zodiac and the tetramorph, any symbolic group of twelve can be contracted to four heads.) In chiastic correspondence (ω.), they return to Capernaum where the paralytic — “borne of four” — is lowered through the roof like the mind into the heart to receive the forgiveness of sins and healing from paralysis betokening the life of the age to come. In the intermediate layer of the chiasmus, Jesus first of all (β.) garners fame by expelling an unclean spirit from a man at the synagogue, which spirit confesses Jesus to be the Holy [One] of God — which exorcisms continue in the parallel passage (ο.) and are expanded upon in the healing of a leper, cleansing not just spirit but body, and unwillingly garnering even more fame. The crowds choke Him out of the city and force Him into desert places, highly reminiscent of the Church history to come; this is ecclesial typology of the historical variety if I’ve ever seen it.

This pentadic chiasmus is then crowned with a fractal triad to make an octave. First Jesus dines with a fresh convert, Levi the publican (ς.), because they that are whole have no need of a physician, but they that are sick; He came to call not the righteous but sinners to repentance. This purification is followed by the confrontations with the Pharisees over the meaning of the sabbath to which I’ve alluded (ζ.), the ones culminating in the Pharisees taking counsel with the Herodians to destroy Jesus, already in chapter 3, verse 6 of the Gospel. This illumination of the meaning of the sabbath is followed poetically by a withdrawal to the sea (η.), an image of the kingdom to come, with crowds of believers flocking to Jesus from Judea, Galilee, and beyond, from Tyre and Sidon, the Phoenician ports leading to the rest of the world. Here even the unclean spirits fall down before Him and confess, “Thou art the Son of God” (3:11).

Without the intro, then, this octave-shaped section establishing the initiation of Jesus the Son of God’s ministry to the world already fulfills the larger octave structure we’ve been tracing from end to beginning:

The first fifteen verses of the Gospel therefore comprise a sort of introduction, but perusing their contents, one finds the passage to be much more substantial than what a mere formal introduction would suggest.

This prologue covering the appearance of the Son of God in the world, His entrance into public life before the beginning of His ministry represents something especially foundational to the cosmos. The effect is as if the evangelist is establishing typologically the presence of an eternal eighth day already at the beginning of sevenfold time. From the chaos of sin is brought the order of repentance. From the death of the waters is brought the life of the kingdom. Creation is Theophany, and Theophany is creation.

The Christian week, as it is experienced liturgically, provides a perfect model for the structure of Mark’s text, as Sunday is both the first day of the week and already symbolic of the eighth day of the week. I wrote about the Christian liturgical week recently here in the Journal, and I preface the outlines of this Gospel on my website with a bit more description of how the Christian week applies to Mark. If you’re wondering about the vesperal labels I’ve used for the different parts of the octave, that’s where you’ll read about that. I find the use of vesperal thresholds a more fruitful way of understanding the pattern than the bare form of the outline I’ve been building up to here:

And as I mentioned way back towards the beginning, this structure of a week with a blank sabbath, interpenetrated from the beginning with the eighth day, is found also in Bright Week, the sequence of celebrations initiated by Pascha. All throughout the year, the Church follows an eight-week liturgical sequence known as the Octoechos. Each week has a different musical tone, with different texts of prayers to match. Thus there are eight different Sunday services celebrating the Resurrection, which the Church cycles through throughout the year. But each Sunday already is Pascha. And Bright Week recognizes this by using those resurrectional services one a day for the duration of the Paschal week. Pascha Sunday is already in tone 1 as the first day of the eternal week containing all time. Then Bright Monday is in tone 2, Tuesday in tone 3, etc., each day using the resurrectional hymns from the Octoechos. The sequence ends on Bright Saturday, however, in preparation for the eighth day of Pascha, known as Anti-Pascha, which has its own service dedicated to the events narrated in the Gospel of John concerning what happened historically a week after Pascha (Thomas Sunday). So while Bright Friday uses the tone 6 resurrectional service from the Octoechos, Bright Saturday skips tone 7 and goes straight to tone 8. The seventh, the sabbath, is symbolic of death, and in Bright Week truly the kingdom of heaven is established on earth — death is no more. It has become fully transparent, and the light of the eighth day shines through it and suffuses the whole. This is the gospel of the kingdom of heaven. This is the what the Evangelist Mark would have us know and participate in.

And so, courtesy of the evangelist, along with the Triune God who works through him, we have an octave-shaped Gospel, one with a fully transparent seventh part. This understanding of the Gospel according to St. Mark yields plentiful crops of contemplative sustenance — and I think it also diffuses the ambiguity of the textual tradition regarding the ending. The Church from ancient times has proliferated the longer version of the final chapter, with which we are commonly familiar. Scholarship into ancient manuscripts and secondary sources, however, reveals less than a consensus in the “originality” of everything after 16:8. An octave structure of the Gospel, however, does not depend on the presence of 16:9–20. I do find the extra text yields a beautiful internal stucture, though:

In my experience, whenever there is discrepancy among textual traditions, the Church always proliferates the most beautiful version. The idea of “originality” that scholars deploy is overblown and misunderstood. Their dialectical minds don’t understand how writing works or how authorship works.

I rely on input from others for the best things I write. If some digital archaeologist of the future were to dig up an earlier version of something I’ve written and claim that merely because it’s dated earlier, that is the “real” version of the text, despite it being demonstrably a worse version of itself, well, then, let me speak from beyond the grave to tell them they’re silly and wrong. It’s easy to imagine the Apostle Mark leaving a draft in one city and traveling to another to receive feedback, or to do extra research, and there to complete what he has written. Or maybe he wasn’t able to, or was unsure of doing so, and a disciple operating in inspired faithfulness completed the job. The other books of Scripture — the Books of Moses, the Psalms of David, the Book of Isaiah — all seem to demonstrate that the highest form of authorship is actually to form souls capable of speaking in one’s voice after one is gone. The main thrust of the biblical tradition is less about writing books than it is about authoring souls. And this continuation of one’s voice beyond death through spiritual descendants is actually symbolic of resurrection. The Church likes resurrection and revels in it where she can. For her there is no issue in including Mark 16:9–20 among the regular cycle of resurrectional Gospel readings (the eleven eothina read at dawn on Sundays) or in attributing it to Mark. According to the larger symbolic sense of his authorial body — no matter what — he wrote it, and this fuller text is (in some sense objectively) the most beautiful version of what he wrote.

Hey Cormac,

I am new to your substack. Could you point me to some beginner level resources (either your own here or a book or article) outlining the basics of things like chiasm and patterns in biblical texts and why these patterns matter? I know this is important, but I do not know why yet, and I need a kindergarten level primer for it.

Thanks