The initiation of dialectic in ancient Greece

How philosophy was prefigured by advances in vase painting

I remain very tied up with things other than Substack momentarily, so this week again I’m publishing something old, but something that is very relevant to what I want to do here. This essay I wrote all the way back in December of 2000, a couple weeks before my twenty-first birthday. Already evident, though, is the analogical thinking that would serve me very well going forward, even when — especially when — looking at dialectical subject matter.

This analogical approach is operative, for example, when in latter days I’ve come to see the pattern of dialectic described in the essay below (an interplay of negation and opposition founded in rebellion) as conforming to the pattern of the lower passions thymos and epithymia, which I’ve described previously in this space as, respectively, the seats of repulsion and attraction in the soul. As desire (epithymia) gapes with appetite for the objects of the will, so the unity of opposites championed by Heraclitus is such that they rely on each other for meaning and thus compel each other’s existence. Likewise, as anger (thymos) repels obstacles to the will, so the non-contradiction–based reasoning epitomized by Parmenides negates opposites such that they exclude one other.

Even today our physical models of the universe have not progressed any further. General relativity relies on the attraction of gravity to show how everything is related in unity. Meanwhile the antinomy of quantum mechanics yields a multiversal cosmology as if the world is fractally repulsed by itself at every moment, in every place. Both theories are the products of impassioned minds relying on dialectic to conjure the laws of the cosmos. Analogously, then, quantum mechanics represents the thymic end of the polarized mind, general relativity the epithymetic end — the illustration of a bar magnet remains apropos in this context.

Dialectic follows the patterns of the passions. For matter, maybe, it is a natural rhythm — if I’ve implied that modern physics is all in the head, I should clarify I don’t believe it is only in the head. For the mind, however, subjugation to the rhythm of matter, viz. dialectic, comprises the logic of rebellion and is evidence of a soul being destroyed by polarization. It is the knowledge of good and evil tasted in disobedience. For created beings trying to originate meaning from the self like a god, dialectic represents the most powerful option, but I would say this is a type of suicide.

For indeed I describe dialectic like death, and intentially so, because as with death, in Christ it is possible to turn dialectic into glory. Such a Paschal motion was achieved by the Church in the era of the Ecumenical Councils, for example. The Hellenism based on the dialectical logic of the passions first thrust itself onto God’s people in the time of Alexander the Great, whose early demise gave way to a divided empire that the prophet Daniel described in terms of the King of the North (Seleucid Syria) and the King of the South (Ptolemaic Egypt). The battles between these poles — relative to each other, the imperious Seleucids were thymos on the north pole of the magnetic field, while the learned Ptolemies were epithymia on the south pole — routinely seduced and thrashed the Judean remnant of Israel caught between them like a soul repeatedly desecrated by the passions. Under such apocalyptic pressure the valorous martyrdom of the Seven Maccabees showed a new Judean approach to death that would prefigure Christ’s own. Then the blood of the martyrs became the seeds of the Church, and, as a token of Christ’s victory over death, the Roman Empire which had marshalled the passions of Hellenism under one emboldened ratio (the Latin logos) was converted. From Constantine until the Triumph of Orthodoxy in the ninth century, when the dialectic of Hellenistic heresies had finally run its course, it only took five hundred years. The Church Fathers in this time overcame dialectic not by abolishing it but by transforming it, even as they first of all overcame the passions by purifying them.

This is all just a lengthy introduction to the following essay, which I hope to expand on more in the future. As context, I hope this suffices for now. I wrote this essay for a course in ancient philosophy. It was taught by a short old Greek professor with a very Greek name and a thick Greek accent. He always wore a suit, was always clean shaven, and had finely sculpted silver hair that visually stood out from his weathered olive skin. I remember he had a mouth like a turtle, with a little pointy tongue, and he would spur on his pupils with spittle-laden shouts of “Di‑aaa‑lectic!” The class after this paper was submitted, he sought me out beforehand and told me it was “really good”, asking me to come see him at office hours. When I did, the conversation didn’t get too far before it came up that I was a recent convert to the Orthodox Church. I remember seeing the light go out of his eyes as his interest in me as a student immediately dissipated. “You really believe in all that stuff?” he asked with cocked head, wincing in disappointment. I replied that I did and held back from elaborating. I was a young, dumb convert, sure, but not dumb enough to miss that this old Greek man already knew everything he was ever going to know about the Orthodox Church. Partial to dialectic as he was, I suppose he missed the irony of my paper’s final line, that the finale of dialectic was “pending.” The implication is that dialectical progress, left to its own devices, is eternally pending, forever subject to an unsatisfiable appetite for opposition and a contradictory drive to negate — or in biblical language, to weeping and gnashing of teeth.

Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Parmenides —

and the Initiation of Dialectic in History

Exekias, the Andokides Painter, and Euphronios

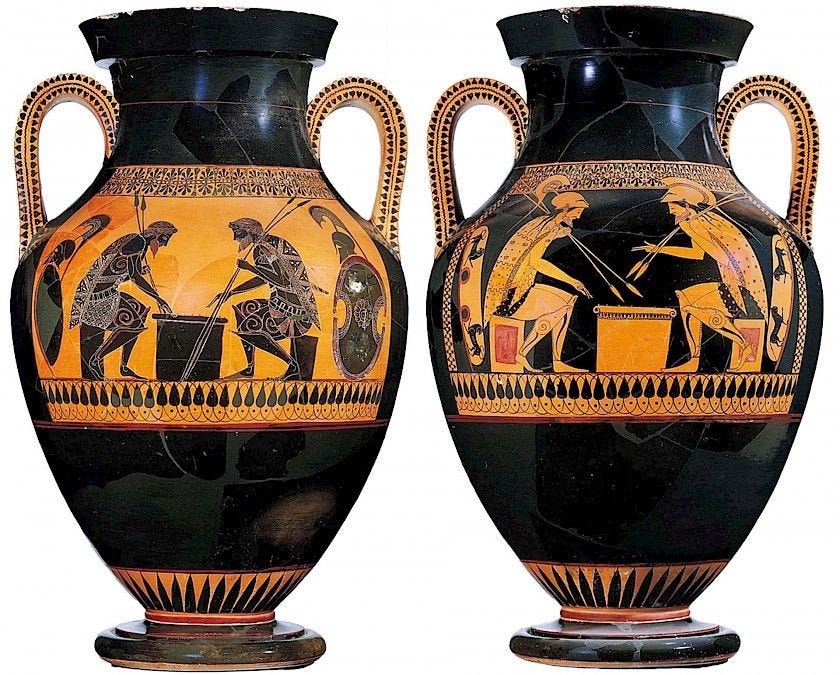

Two warriors, who are friends, oppose each other in a peaceful contest before they battle together in opposition to their enemy. Such is dialectic, the play of opposites. In opposition to the Archaic predilection for activity, the revolutionary vase painter Exekias [see the detail at top, as well as the full image that follows] depicts a calm scene that actually feels anything but. The content is charged with its opposite, the violence of war (i.e., opposition), and thus imparts its tension in a unique and powerful way. Even peace contains the horror of war when it is defined as the opposite of opposition.

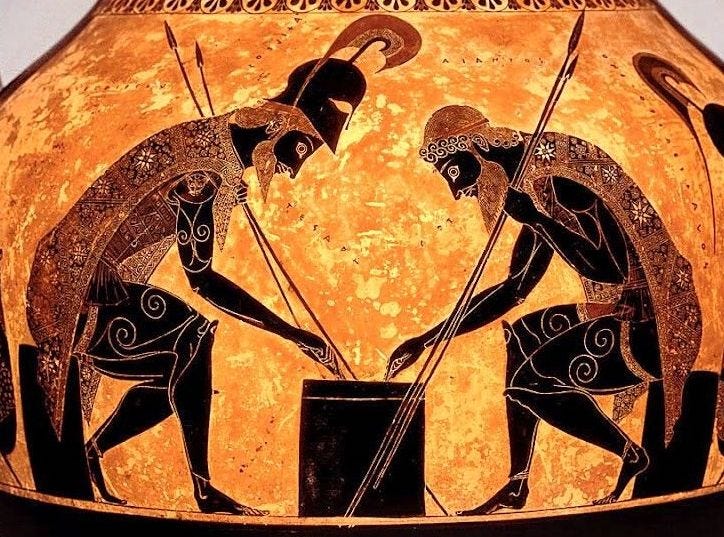

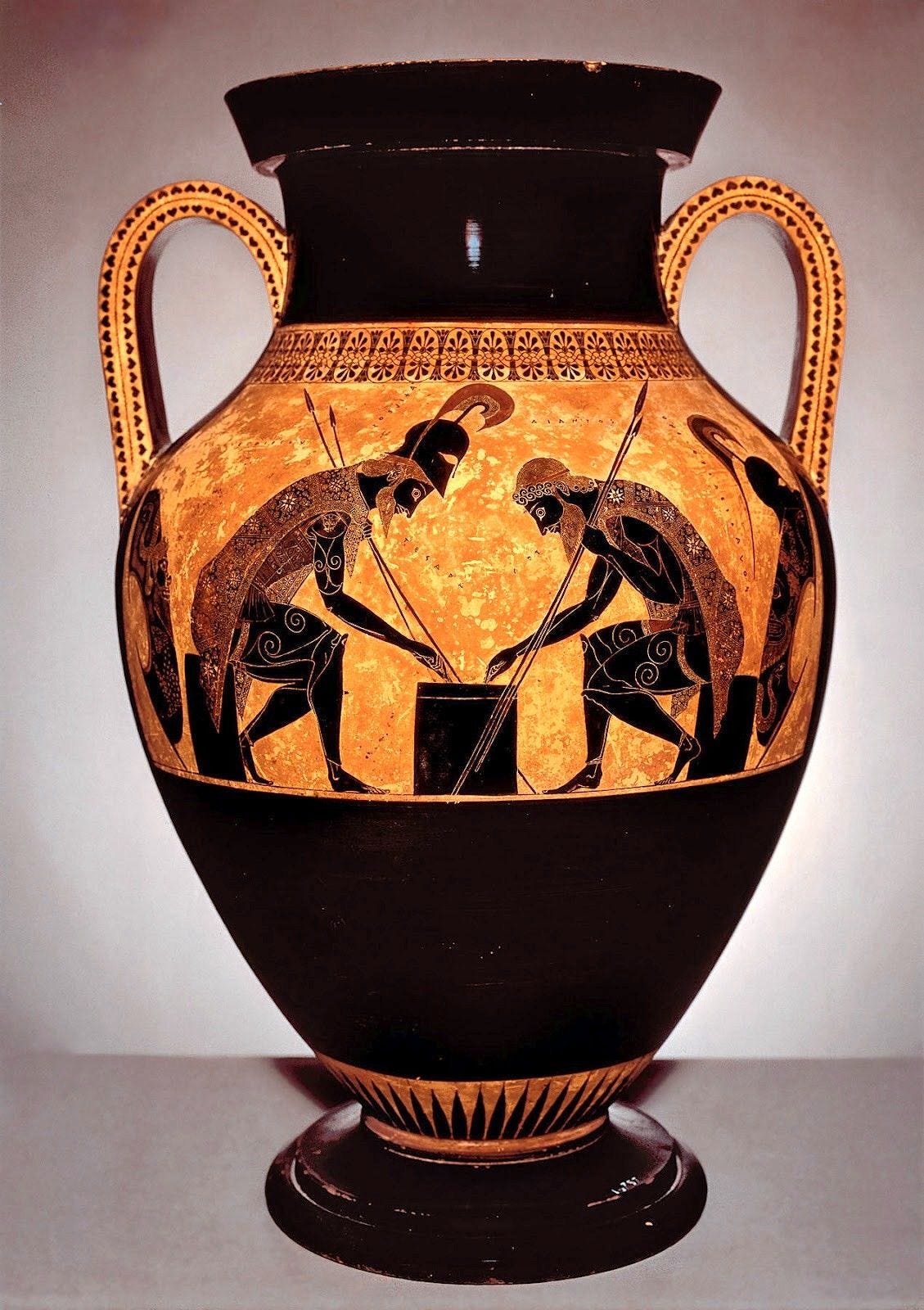

The Andokides Painter, in response to Exekias, expresses this theme technically in a revolution of his own [see the double image immediately above].1 In contrast to painting black figures on a red vase, he first outlines the figures to be drawn and then fills in the background of negative space. Detailing the figures, which are now red against black, the anonymous painter of the potter Andokides’s vases has created a method that leads directly into a world of new versatility and inventiveness. Another painter Euphronios [see the image below] uses the red-figure style to venture into an illusory third dimension — examine the figure of Antaios on the right and notice his right foot, peeking out from behind him — and man’s perception of images will never be the same.

The literary and philosophical analogue, roughly contemporary though definitely subsequent, of this aesthetic revolution is found in Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Parmenides. Richard D. McKirahan, Jr.’s Philosophy Before Socrates [PBS]2 and G.S. Kirk and J.E. Raven’s The Presocratic Philosophers [TPP]3 provide the text for the following discussion.

Xenophanes

Inasmuch that Xenophanes (fl. 540–537 BC) is the pinnacle of the Ionian tradition, he represents the diametric opposition to the past implicit in Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes. The rebellion, seen also in Exekias, is characterized by a rejection of tradition in favor of rational criteria. This move involves more than just diametric opposition but complete contradiction, as will be made evident with further discussion. The traditional pagan Greek worldview maintains a plurality of anthropomorphic gods who control the world through dramatic intrigue among themselves and others. Xenophanes switches the many into its opposite, the one, saying, “God is one, greatest among gods and men, / not at all like mortals in body or thought” (PBS 62). Writing polemically, his ideas are a direct reaction to what he sees wrong with traditional belief. In contrast to the activity of the Olympians, Xenophanes’s god is motionless and controls things rather with the power of his phren, his thought or active will. This move bears similarities to Exekias’s switch from Archaic activity to an eerie calm that strikes the viewer not outwardly but with the dialectic charge of tragic fate — witness Aeschylus’s application of the idea: “(Zeus) hurls mortals in destruction from their high-towered expectations, but puts forth no force: everything of gods is without toil. Sitting, he nevertheless at once accomplishes his thought, somehow, from his holy resting-place” (Supplices 96–103, TPP 171).

The epistemological implications of such an utterly new stance are reflected in Xenophanes’s fragments. If all previous thought is fallacious, what of knowledge? It is not had by anyone, but “belief is fashioned over all things” (PBS 67). Nevertheless, Xenophanes defends why he should be believed above all, saying, “...the gods have not revealed all things from the beginning; but by seeking, men find out better in time” (TPP 179). He knows better, or rather believes better, because having more past behind him, he benefits from more research. This radically new thought of intellectual progress, placed in the context of Xenophanes’s agnostic worldview, provides the incipient mission statement for a project embraced by those that follow and continuing to the present. It is the path of constant rebellion, of continuous discontinuity — a harmony of opposites that proceeds from contradiction.

Heraclitus

“We should not be children of our parents” (PBS 117), Heraclitus says (ca. 500 BC), continuing this anti-tradition; he elsewhere lists Xenophanes among those who have no insight. A harmony of opposites, however, is exactly what Heraclitus achieves, calling it the Logos and setting it as the underlying principle of a world in flux. Xenophanes in his physical thought says that all things are earth and water and describes the eternal existence of the world as lying on a continuum of wet and dry. Heraclitus takes these kinds of ideas and expands them into a magnificent system based on the unity of opposites. In Heraclitus is found the philosophical explanation of Exekias’s artistic achievement: “It is necessary to know that war is common and justice is strife and that all things happen in accordance with strife and necessity” (124). The Logos is dialectic, or opposition, or strife — “War is the father of all and king of all...” (TPP 195).

When things are defined by their opposites, a binding dependence exists between them, for they depend on each other for their very meaning. Of this Heraclitus says, “Disease makes health pleasant and good, hunger satiety, weariness rest” (PBS 123). In Exekias’s portrayal of Achilles and Ajax playing dice (and this is continued in the bilingual amphora of the Andokides Painter), the scene of peace attains its power only from its opposite, war — this is Heraclitus’s Logos in action. “An unapparent connection (harmonia) is stronger than an apparent one” (121), Heraclitus explains. The subliminal depiction of war (i.e., the Logos) in the vases of the present discussion is stronger than the Archaic depictions of war that proceed them. For the final word on the matter, Heraclitus declares, “What is opposed brings together; the finest harmony is composed of things at variance, and everything comes to be [or, occurs] in accordance with strife” (121).

All that has been said so far about Heraclitus is akin to the achievement of Exekias, but the philosopher proceeds in such a way as to depict himself as on one side of a coin — as on the black-figure half of the Andokides Painter’s amphora. Heraclitus describes the world as being in flux. The history of this belief can be said to begin with Xenophanes’s monotheistic reaction to polytheism and the initiation of the dialectic between the one and the many. Heraclitus writes, “Changing [or, by changing] it is at rest,” and “Even the posset separates if not being stirred” (124). Posset (a kind of mixed drink) is one and its components are many, but for Heraclitus, unity is only found in plurality, as rest is found only in change. Regardless it is flux that he appears to emphasize saying, “Upon those that step into the same rivers different and different waters flow.... It scatters and ... gathers ... it comes together and flows away ... approaches and departs” (TPP 196). Important to note, however, is that the rivers of different waters are nevertheless called the same, and that Heraclitus’s doctrine of flux is not the extreme “Heraclitean flux” later ascribed to him by the likes of Plato (see PBS 142–44 and TPP 196–99). Unity and plurality, motion and rest are merely pairs of harmonically balanced opposites included in the Logos.

Previous to Heraclitus, the Ionian philosophers established a tradition of naming an arche, a first principle that underlies and/or is the source of the physical world. For Thales it is water, Anaximander the infinite, Anaximenes air, and Xenophanes the one god. Heraclitus calls it generically the Logos, and being the arche, that it is one and unchanging is a given (in truth, however, not all arches have been the latter, unchanging; Xenophanes sets that tradition). How, though, does Heraclitus define the Logos? By its opposite, necessarily; according to the dialectic of Heraclitus, a thing is defined by its opposite. In this way does flux define the world. Since this definition in fact accords with the harmony of opposites, any imbalance in this regard is merely perceived due to historical circumstances. However, it is perceived as such not only by others, but also by Heraclitus himself — the real imbalance is found in his epistemology.

The separation of sense perception and reason occurs first in the thought of Heraclitus, and he clearly has a preference: “The things of which there is seeing and hearing and perception, these do I prefer” (TPP 189). He does qualify this statement, however, saying, “Evil witnesses are eyes and ears for men, if they have souls that do not understand their language” (TPP 189). He therefore roots his knowledge primarily in sense perception though qualifying it with the “soul” — what can be understood to mean reason. This epistemological hierarchy is the result of a perceived imbalance between plural flux and monistic rest. Sense perception is of the present moment and lacks the time to be reflective. With the eyes, one sees only the flux between day and night and does not comprehend, as does the qualifying soul, that “day and night ... are one” (PBS 123). Because Heraclitus defines the world as being in flux, moreover, he therefore grants flux-perceiving senses priority over reason. The imbalance is unfortunate because one can see that, according to dialectic, reason and the senses — just as the one and the many that they respectively perceive — should be treated as diametric opposites of equal force.

Parmenides

In fact the imbalance appears tragic, as if compelling a contrary reaction to a lopsided epistemology and falsely perceived doctrine of flux. Parmenides (fl. circa 475 BC) is the red-figure revolution of the Andokides Painter, the flip side to the old black-figure style of Heraclitus. Although Heraclitus’s epistemological orientation has considerable importance to his thought, it is only cursorily mentioned in the extant fragments. Parmenides thoroughly explores it and explodes it. He asserts the primacy of reason and not only demotes sense perception but denies it altogether. Accordingly, he denies all plurality and motion. “It is,” is ultimately all Parmenides can say about anything and everything.

That which leads Parmenides to these beliefs is logical deduction, and therein lies the true revolution he accomplishes. Where the Andokides Painter fills negative space rather than positive, Parmenides depicts dialectic not positively as diametric opposition, but negatively as mutually exclusive contradiction. Diametric opposition presents a pair of arrows face-to-face as it were, directed towards and against each other; as reference to a diameter suggests, the two forces result in a single sphere. Contradiction, on the other hand, places the arrows back-to-back, facing contrary directions and infinitely contradicting each other. Rather than spherical, it is linear.

Thus in Parmenides’s worldview there are three ways of going about things. The first two ways are the two mutually exclusive directions on the line of contradiction. The third way is that “on which mortals wander knowing nothing, two-headed; ...who are persuaded that to be [i.e., the first way] and to be-not [i.e., the second way] are the same, and that of all things the path is backward-turning” (TPP 271). In the third way, Parmenides describes oppositional dialectic without distinguishing it as such. He uses criteria based on linear contradiction to judge the nature of diametric opposition, which accordingly fails. Now let it be said that opposition and contradiction appear not to oppose each other, but to contradict each other. In Heraclitus’s mode of thinking, as he himself says, “What is opposed brings together” (PBS 121); opposites define each other and therefore compel each other. To posit one is automatically to affirm the existence of the other. In a contradiction, conversely, even as the positive space and negative space of the Andokides Painter contradict each other, to posit one thing is automatically to negate the other. Unless, therefore, one can simultaneously affirm and negate something, opposition and contradiction contradict. In other words, to say two sides of a linear contradiction can be spherically joined is on its face absurd — one would have to be either Christian or Nietzsche to believe such a thing, and no such options exist in ancient Greece.

Interestingly, however, Heraclitus once comes close to uttering just that when writing, “The path up and down are one and the same” (TPP 189). He does not, however, place a perspective on this path that looks up and down, but rather takes the path as a whole. In the passage that introduces Parmenides’s philosophy, he describes a goddess leading him into a doorway that is formed by a lintel bridging two other, presumably opposed, doorways — that which leads to the path of Day and that which leads to the path of Night. Only once Parmenides is in the doorway does the goddess dictate his non-contradiction–based philosophy to him. This detail signifies that two contradicting paths (the doorways are opposed, but to face them one must look in contradicting directions), such as the past and the future, require a perspective between them, such as the present, in order for the contradiction to occur. In not taking such a perspective, Heraclitus might as well mean hot and cold when he says up and down, for by them he means mutually affirming diametrical opposites.

To return solely to Parmenides, that he discovers a method that negates by contradiction rather than compels by opposition leads him to an entirely new way of contemplating things — just as does the red-figure style for the painter Euphronios. By taking the negative outline of images, Euphronios begins to see a fictive third dimension within the two-dimensional surface. The analogous benefit for Parmenides is logical deduction, and the inaugural pair for this new mode of thinking is “It is” and “It is not.” In poetic verse he delineates

the only ways of inquiry there are to think:

the one, that it is and that it is not possible for it not to be,

is the path of Persuasion (for it attends upon Truth),

the other, that it is not and that it is necessary for it not to be,

this I point out to you to be a path completely unlearnable,

for neither may you know that which is not (for it is not to be accomplished) nor may you declare it. (PBS 152)

The rest of Parmenides’s thought is the process of logically deducing the implications of this premise (Premise A). First of all, a thing cannot come to be or perish (Conclusion A). If it could do either (Premise B), at some point it could be said that it is not (Conclusion B). Conclusion B contradicts Premise A for a thing cannot be said not to be; therefore Premise B is negated, and therefore: conclusion A, a thing cannot come to be or perish.

Continuing this train of thought, Parmenides proceeds to deny time and all temporal distinctions. He asks, “How could what is be in the future? How could it come to be? / For if it came into being, it is not, nor <is it> if it is ever going to be” (PBS 154). The same logic applies to the past. Here Parmenides places not only the past and the future in contradiction to each other (both extending in contrary directions from the present, as in his doorway imagery), but he also places the present in contradiction to the future and the past. The question, “How could what is be in the future?” excludes the possibility that something could maintain identity through time. What exists at present can not endure a future that implies change in very contradiction to the present. Moreover, if something exists in the future, that means it does not exist in the present, and at some point it came to be. Nothing, of course, can be said to come to be, nor can anything in the present be said not to exist. Therefore, insofar that temporal distinction is equated with existential change, it is negated from being: “Nor is [that which is] divided, since all is alike; / ... / Therefore, it is all continuous, for what is draws near to what is” (PBS 154).

Not unexpectedly (if madly), the same logic applies to space, and all spatial distinction is obliterated as well. In the end, “Remaining the same in the same and by itself it [i.e., what is] lies / and so stays there fixed; for mighty Necessity / holds it in the bonds of a limit, which pens it in all around” (PBS 154). Parmenides concludes by describing his great “what is” as a perfect sphere, “like the bulk of a well-rounded ball” (154). Its boundaries are not spatial or temporal — indeed in these regards it is infinite, “without start or finish” (154) — but rather entirely conceptual.

Parmenides’s entire system is conceptual — in contradistinction to the sense perception preferred by Heraclitus. His method is characterized by apparently undeniable premises that lead inevitably to conclusions that exist in sharp contradiction to common sense. “But judge by reason the heavily contested refutation / spoken by me” (PBS 153), he exhorts. This separation of reason and perception, started by Heraclitus and finalized by Parmenides, will define philosophical arguments for centuries to come. Euphronios’s fictive third dimension likewise leads to a long tradition...

Uncanny

The analogy is uncanny. Exekias and Xenophanes begin with reactions against tradition. The Andokides Painter creates on one side of an amphora a pastiche of Exekias; likewise Heraclitus expands on thought implicit in Xenophanes, namely the harmony of opposites so prevalent in the pastiched Exekias — but Heraclitus is a bit one-sided. Parmenides reacts, placing himself on the flip side of the vase with the contrary views. To make this jump he, as well as the Andokides Painter, switches from a dialectic of opposition to one of contradiction. Euphronios, dealing likewise with the contradiction of positive and negative, discovers a new fictive dimension akin to Parmenides’s new logical dimension in that they both proceed from contradiction and lead to long anti-traditions that continue to exist in the present day. It all can be said to begin with Xenophanes’s mission statement for continuous discontinuity, a project entailing intellectual progress within an agnostic worldview. The finale — is pending.

Concerning this amphora, we find on the Museum of Fine Arts Boston website the following attribution: “Although the Andokides Painter is credited with the red-figure composition on this vase and the Lysippides Painter with the black, researchers debate whether one person or two painted the vessel; both names may refer to the same artist.” See collections.mfa.org/objects/153408.

Richard D. McKirahan, Jr., Philosophy Before Socrates (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1994). Abbreviated in this essay as PBS.

G.S. Kirk and J.E. Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1957). Abbreviated in this essay as TPP.

Fascinating article! I read it with much ignorance unfortunately so I let the ideas reveal themselves as art and it seems to work. As well, these ancient vases were almost a complete enigma to my eye and now they have a bit of place, which is very settling.