The earth was divided in the days of Peleg son of Eber (Gen. 10:25), Eber being the name from which the ethnonym Hebrew is derived. It means ‘to cross over’, as when Abraham would cross over the Euphrates, or as when Israel would cross over the Red Sea out of slavery, and again over the Jordan into the Promised Land. The line of Eber and Peleg descends from Shem and Noah, ultimately Seth and Adam — Seth who is made in the image of Adam (Gen. 5:3), and Adam who is made in the image of God and is called son of God (Gen. 1:26–27; Luke 3:38). This whole patrilineal genealogy is the story of how we humans are to be sons and heirs of our Creator.

I say the earth was divided in the days of Peleg, which is a reference to the destructively premature attempts at global unity made at the Tower of Babel, how the seventy-fold cleavage of nations precipitated from this rashness. In the divided earth, the heirs of Adam and Seth, of Noah and Shem, of Eber and Peleg were losing their grip on life, gradually decreasing in lifespan as the seed of death was at work in the world. Eternal darkness appeared to have prevailed by the time of Abram son of Terah, when the holy line of divine sonship looked as if dead and buried in Sarai’s barren womb. The Bible is not telling the stories of other peoples at this time. It doesn’t have to; this is the most important story, the one that stands for them all, the one without which no other stories can exist.

From a barren womb, from a world of death, from an earth without form and void, the Lord brought forth resurrection. He brought forth life. He restored our divine kinship, the image of God within us. He created a new nation. Sarai became Sarah, and she brought forth Isaac, who fathered Jacob, who became Israel. Israel fathered twelve tribes, the family of God. The princely line was found in Judah son of Israel, and from him was raised up King David, the anointed one. David ruled over all Israel, but he sinned badly before the Lord, falling prey to the passions of lust and murder (desire and anger). He repented and was restored. He was accounted blameless before the Lord. The offspring from Bathsheba (the woman whom he took lustfully, and whose husband he had murdered) was allowed to die mercifully in infancy, and to her and David in repentance was born a new son Solomon, who would build a house of God in the Judean city of Jerusalem. The Lord would descend on this city, in the holy place within this Temple, in a cloud of glory, the earth being raised up to heaven and crossing over beyond. King Solomon would be graced with all wisdom and knowledge, and his kingdom would rule over all. This is the end of the story — but only in type.

Outside that limited instance of this fractal pattern, the story goes on. King Solomon who taught all the sons of Israel to avoid the seduction of foreign women (as in the Book of Proverbs) himself fell prey to the desire for foreign women, even worshiping their gods, and the wrath of antagonism followed. The Temple which was to foreshadow the New Jerusalem became instead like another Babel, for as in the days of Peleg, the kingdom was divided. First it was cut into two, north and south, but the ten northern tribes were carried away by the Assyrians. The southern kingdom, centered in Jerusalem and known as Judea after Judah, was warned that this catastrophe could happen to them too — and then it did. On account of their attachment to the passions, the Lord’s holy people were carried out of the holy land like a soul leaving its body. From the death of this Babylonian exile, the Lord again raised up His people, for the sake of His promise to David His anointed one. The Judeans were restored to their land, Jerusalem was rebuilt, and a new, resurrected Temple awaited the glory of God.

It did not come, not for a long while, and when it did, it was not at all as expected. In the meantime the Judeans were throttled by hostile powers, first the Hellenes, whose dialectical harnessing of the passions manifested itself in Seleucid Syria and Ptolemaic Egypt warring and seducing on either side of Judea. Then the Romans embodied those passions in one centralized, world-dominating power, Judea becoming just one of many subjects. These Romans cemented their authority by building infrastructure, and their Judean vassal Herod the Great renovated and expanded the Temple in Jerusalem, be it an emblem of the Kingdom to come or just another Babel. The time was right for the Lord to descend on it either way.

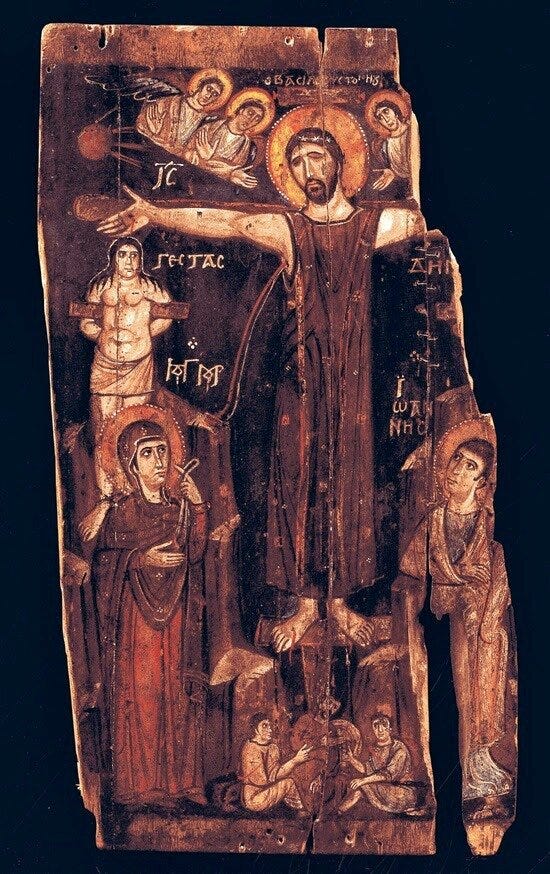

Instead of a cloud of glory, however — the Holy Spirit as a cloud inhabiting Judean history and carrying it along towards its predetermined purpose — the Son of David, the Anointed One, the Christ, the Son and Word of God Himself entered the Temple in the flesh, being in the form of God and yet taking the form of a servant, coming in the likeness of men (cf. Phil. 2:5–11). He thus attended the Temple regularly and ritually, the Lawgiver Himself submitting to the Law alongside His people. He preached against sin with manifest authority; He effected the forgiveness of sins; and He worked signs and wonders against the ravages of bodily corruption.

Many Judeans followed Him and believed on Him, but leaders among them rejected Him, preferring their own subservient power. The scandal of that power caused their subjects to dishonor themselves and incited Christ’s disciples to flee. As a people the Judeans failed to receive their Christ. They delivered Him to the Romans to be crucified. The Romans of course failed to receive the Christ, too, but they were like animals of whom nothing was ever expected. The Judeans had been prepared for this; they represented the best of humanity, the image of God within man. To say they failed is synecdochically to indicate the failure of all humanity. That means you. The Judeans are you.

Anagogically, the Judeans are that part of you that is the best, that has been prepared to receive God — they are the image of God the Father, the Son, and the Spirit, within humanity: your nous, your logos, your pneuma. When you read a story about the Judeans failing, you are reading the story of your own failing before God, in nous, in logos, and in pneuma. You read about this so that you may repent. This pattern you read about in Scripture of bringing light out of darkness, righteousness out of sin, habitation out of exile, wisdom out of ignorance, life out of death, is meant to be enacted in you, lost in sin and darkness though you are. When the grace of God’s forgiveness visits your soul and you are no longer captive to passions which previously ruled over you, you can truly testify to Christ’s resurrection from the dead.

This anagogic hermeneutic is how the Church expects the faithful to engage with its revealed texts. When the Judeans saw the Northern Kingdom of Israel conquered by the Assyrians and exiled among the nations, they were not to point and feel superior but to understand that such obliteration was a vision of the very fate that awaited them should they not repent and begin behaving as the sons of God they were meant to be. And in the Epistle to the Romans, the Apostle Paul explains that the disinheritance of the Judeans should be a source of humility and fear among the Gentiles grafted into the Church. For if from the trunk of His olive tree, God casts off natural branches for their lack of faithfulness and instead grafts in wild branches from the Gentiles, these latter branches should by no means be highminded, lest they also be not spared, and then the natural branches be brought back in (cf. Rom. 11:16–24). Subsequent history has evidenced at work in the Church the same pattern of longsuffering and impending wrath that God showed His people of yore.

When the faithful of the Church lose their faithfulness, their hermeneutic suffers, and they no longer understand revelation as they should. Instead of persecuting sin in themselves, according to an anagogical reading, they persecute sin in others so as to define themselves as righteous in opposition, falling as though deliberately into unrighteousness. This is Holy Week, the time of the holiest services of the year, and the texts that the Church prays on this occasion say many things about the Judeans that are vulnerable to crooked, self-defeating misinterpretation. This vulnerability, I think, is a feature, not a bug. These events we are liturgically witnessing are apocalyptic, and they will reveal by way of our interpretation whether we are to be worthy of the Kingdom or not.

Last week for example, at Matins on Wednesday, the Church prayed (for this is a prayer):

Israel was clothed in purple and fine linen, arrayed in the glory of priestly and royal garments; rich in the Law and the Prophets, it rejoiced in the worship of the Old Covenant. But it crucified Thee outside the gates, O Benefactor who hast made Thyself poor, and it rejected Thee when Thou hast returned alive after the Crucifixion, O Thou who art ever in the bosom of God the Father. Israel thirsts now for a single drop of grace, like the rich man clothed in purple and fine linen, who showed no mercy to Lazarus in his poverty, and so was punished in the fire which never shall be quenched. Israel is filled with anguish as it looks upon the people of the Gentiles, who once lacked even the very crumbs of truth. But now they are comforted in the bosom of the faith of Abraham; they wear the purple of Thy blood and the fine linen of Baptism; and they make glad and rejoice in Thy gifts of grace, saying: O Christ our God, glory to Thee.1

To pray these words with an overliteral, antisemitic understanding would be a grave mistake running in contradiction to the entirety of revelation. The Apostle Paul says variously that in the Church are called both Judean and Gentile (Rom. 9:24), because there is no difference between Judean and Hellene (Rom. 10:12), and that in Christ Jesus there is neither Judean nor Hellene (Gal. 3:28), which is to say that no national identity has precedence over the fullness of human identity recapitulated in Jesus. When a Christian prays words like those above, he or she is to understand them from the perspective of such a full human being. Israel’s behavior towards the Lord, both before and after His death and resurrection, is emblematic of each Christian’s own. Imagine, sinning against the Christ, even after He has risen from the dead! Well, Christians who know their own weaknesses do not have to imagine. We recognize this description of ourselves immediately. In this context the Gentiles are the undeserving ones, the ones upon whom God showered grace freely and abundantly, regardless of their spiritual poverty. By God’s mercy and beyond reason, we recognize ourselves in this depiction, too, through no merit of our own. We are both Judean and Gentile. The comparison of these two to the rich man and Lazarus, moreover, a story which relates eternal states of blessedness and damnation (see Luke 16:19–31), serves as a warning to our souls that our dual identity is destined to calcify in one direction or the other. If we persist in sin and lack of witness to the resurrection of Christ, the image of expulsion we see historically with the Judeans could be a sign of our own eternal fate, we Gentiles who are ostensibly in the Church, clothed with the fine linen of Baptism. Rather we should consign our merciless audacity to everlasting perdition, identifying ourselves instead as meritless sinners raised to the glory of royalty by grace. Go ahead, if you like, and reread the passage above anagogically, as a prayer, recognizing both Israelite and Gentile as versions of yourself.

Try out also these stichera from the service for Palm Sunday, when the non-dialectical contrast of Judean and Gentile is a repeated theme. First from the aposticha at Vespers:

O Thou who ridest on the cherubim and art praised by the seraphim, Thou hast sat, O gracious Lord, like David on a foal, and the children honoured Thee with praise fitting for God; but the Judeans blasphemed unlawfully against Thee. Thy riding on a foal prefigured how the Gentiles, as yet untamed and uninstructed, were to pass from unbelief to faith. Glory be to Thee, O Christ, who alone art merciful and lovest mankind.2

Next this verse from the Praises at Matins:

Come forth, ye nations, and come forth, ye peoples: look today upon the King of heaven, who enters Jerusalem seated upon a humble colt as though upon a lofty throne. O unbelieving and adulterous generation of the Judeans, draw near and look on Him whom once Isaiah saw: He is come for our sakes in the flesh. See how He weds the New Zion, for she is chaste, and rejects the synagogue that is condemned. As at a marriage pure and undefiled, the pure and innocent children gather and sing praises. Let us also sing with them the hymn of the angels: Hosanna in the highest to Him that has great mercy.3

These are prayers that Christians should pray, but they should pray them correctly and not incorrectly. They should read them anagogically, in relationship to the divine, not dialectically in opposition to the human. Otherwise how can this tropar from the selfsame service make sense?

The Church of the saints offers praise to Thee, O Christ, who dwellest in Zion, and Israel rejoices in Thee that made him. The mountains, figuring the stony-hearted Gentiles, exult before Thy face, and they sing to Thee, O Lord, a hymn of victory.4

To define Gentile and Judean dialectically, to see one as good and one as bad, to see one race as damned and one race as saved, is already to be among the cursed. The Judeans who rejected Christ did this, the Pharisaical, rabbinical tradition that survived the destruction of the Temple in the first century. They redefined their religion in opposition to what the ascendant Christians believed and practiced. Christians who are antisemitic do the same in reverse, redefining and making ugly everything they believe in. And Protestants who instead adopt Zionism merely give the dial another twist, not escaping the Germanic dialectic in which they are born and to which they are captive. Do not mistake this Holy Week screed against antisemitism as justification for any violence you read about currently going on in Gaza and Lebanon. Quite the contrary. But such topics run astray from my original purpose.

To be Christian and to be antisemitic is to be cut off from the family of God, and any Judeans whose lives are taken as a result share in the blood of their Anointed One. There is nothing new under the sun, and for the presence of antisemitism in the Gospel account, look no further than Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. He despised the people he ruled over. He saw the same envy and hypocrisy in them that Jesus did; but that’s all he saw, and he hated them for it. He heard them out of one side of their mouth swear that they had no king but Caesar (cf. John 19:15), and out of the other side demand the release of an insurrectionist with blood on his hands instead of an innocent man who presented no threat to anyone (cf. Mark 15:7). In effect both Jesus and Pilate said in response, “Not my will but your will be done,” except Jesus said it to God the Father, establishing His will in good, and Pilate said it to the hypocritical mobs, fixing his will in wickedness. Jesus hence responded to His people in sacrificial love, and Pilate in rebellious hate. It was out of racist anger that Pilate posted on Jesus’s Cross, “This is the King of the Judeans,” because crucifixion is what he would have liked to have done to their king had they been allowed a proper one. Jesus being an effigy of all Judeans, the crucifixion was a synecdochical act of rage on behalf of the Roman governor. Christians repeat it when they succumb to carnal understanding and engage in antisemitism. They play the role of Pilate, and the Judeans who suffer at their hands, the role of Jesus.

All of European nationalism unfortunately partakes of this dialectical hermeneutic. In the 17th-century the dialectic of Reformation and Counter-Reformation blew apart the phony Holy Roman Empire that the Germans had going on. In the process of the ultra-traumatic Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), initiated by religious conflict, the peoples of Central Europe learned to define themselves in opposition to their neighbors, and, like the fallout from the Tower of Babel, the modern nation state was born. Then, next door to the east, in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Slavonic-speaking Orthodox peoples around the Dnieper River, who had centuries before been identified as the Kievan Rus’, got caught up in the spirit. Oppressed by Roman Catholic tyranny, they staged a protest of their own. This is the early origins of Ukrainian national identity, though the name Ukraine was never officially used in this era. Ukraine in the Slavic tongue means borderland. If one were to understand the name symbolically, it would denote a margin, which means it would require an external center; it itself cannot be a center so long as that is how it identifies itself. A symbolic hermeneutic is not, however, how this identity comes to be. Understood dialectically (the way it actually originates), this borderland identity means “I am not you,” and this polarized charge against others has reifying powers.

The Cossack hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky led the rebellion. The Poles and Lithuanians had formed a synthesis of their dual identities that they called a republic. These former Kievan Russkies, nascent Ukrainians, defined themselves in opposition to it, successfully establishing, by violent means, an independent Cossack Hetmanate. And not just to their Roman Catholic overlords did they oppose themselves. For they knew they weren’t Polish, and they knew they weren’t Lithuanian, but they also knew they weren’t Judean. In coming to power, while privileging the Orthodox Church in all policies as if he knew what it meant to do that, Bohdan Khmelnytsky forbade from his territory all Polish military and all Judeans. Thousands of Judeans, as many as tens of thousands, were slain in pogroms that terrorized their descendants for centuries to come. The name Khmelnytsky, for example, casts a pallor of death on the Volhynian shtetl in the story of The Dybbuk filmed by a Yiddish theater group that in 1937 Warsaw was staring down their own annihilation in real time (see my review of this remarkable movie here).

Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky remains to this day a national hero for Ukrainians, a fact that hardly dissuades me from the opinion that Ukrainian national identity, because dialectically defined, is inherently antisemitic. To support his state’s power from hostile forces on all sides, Khmelnytsky eventually forged an alliance with Muscovite Russia, and so he and his antisemitic Cossacks have been heroes to Russia too. The Slavonic-speaking denizens of the Dnieper-centered region thus entered their centuries-long “Little Russia” period, the name Russia offering an interesting point of contrast with Ukraine. Originally the Rus’, centered in Kiev, exercised dominion over modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, and European Russia. They as people collectively were all named Rus’, or in adjectival form Russkies (if you’ll forgive the English pluralization). Their territory was known among themselves as Russky Land, but sources from the Roman Empire called it various forms of Russia. The southern portion of the land dominated by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth came to be known externally as Little Russia, and Great Russia — the epithets referred to the size of their territory — referred to the various principalities comprising modern-day European Russia. In Great Russia, where they internally still called themselves Russky Land, power eventually centralized in Moscow, and the Tatars were finally fended off after centuries of tyranny and abuse. In the 15th century, when the Roman capital Constantinople finally fell to the Turks, the name Russia came to have prominence (over the name Russky Land) among the Russkies themselves. But Great Russia was on its own in independence. Not until Khmelnytsky’s uprising was a door opened for the reunion of all the “Russias” that formerly comprised the land of the Rus’: Little Russia, Great Russia, and eventually White Russia (Belarus).

In adopting the name the Eastern Romans had for their territory — particularly in contrast to “Ruthenia”, by the 15th century the preferred Latin name for the Russky Land — there is present in the Russkies a submission to the source of their faith and a centering of the religious identity by which the image of God in man can be learned. The name Russia I believe is therefore redeemable in a way that Ukraine isn’t unless it adopts the symbolic understanding of margin requiring an external center. But insofar as Russia is a redeemable identity, the people of Kievan Russia have as much claim to it as the people of Muscovite Russia, as do also the people of Minskite Russia, all of them united under the aegis of the Body of Christ, the Orthodox Church. In the names of Little Russia, White Russia, and Great Russia, there is potential for a non-dialectic hermeneutic of identity where people are defined in loving relationship to God and neighbor and not in opposition. That’s not to say that’s the potential that was actualized in history, however. There is also potential for a dialectical understanding, for the triumvirate of Russias to be a dialectical synthesis forged in nationalistic opposition to their nationalistic Western neighbors. To discern which hermeneutic is active, we can ask ourselves: Is antisemitism present? That would be a sign of apostasy among God’s would-be heirs, the type of sign familiar to those conversant in the sacred history of the Old Testament Prophets.

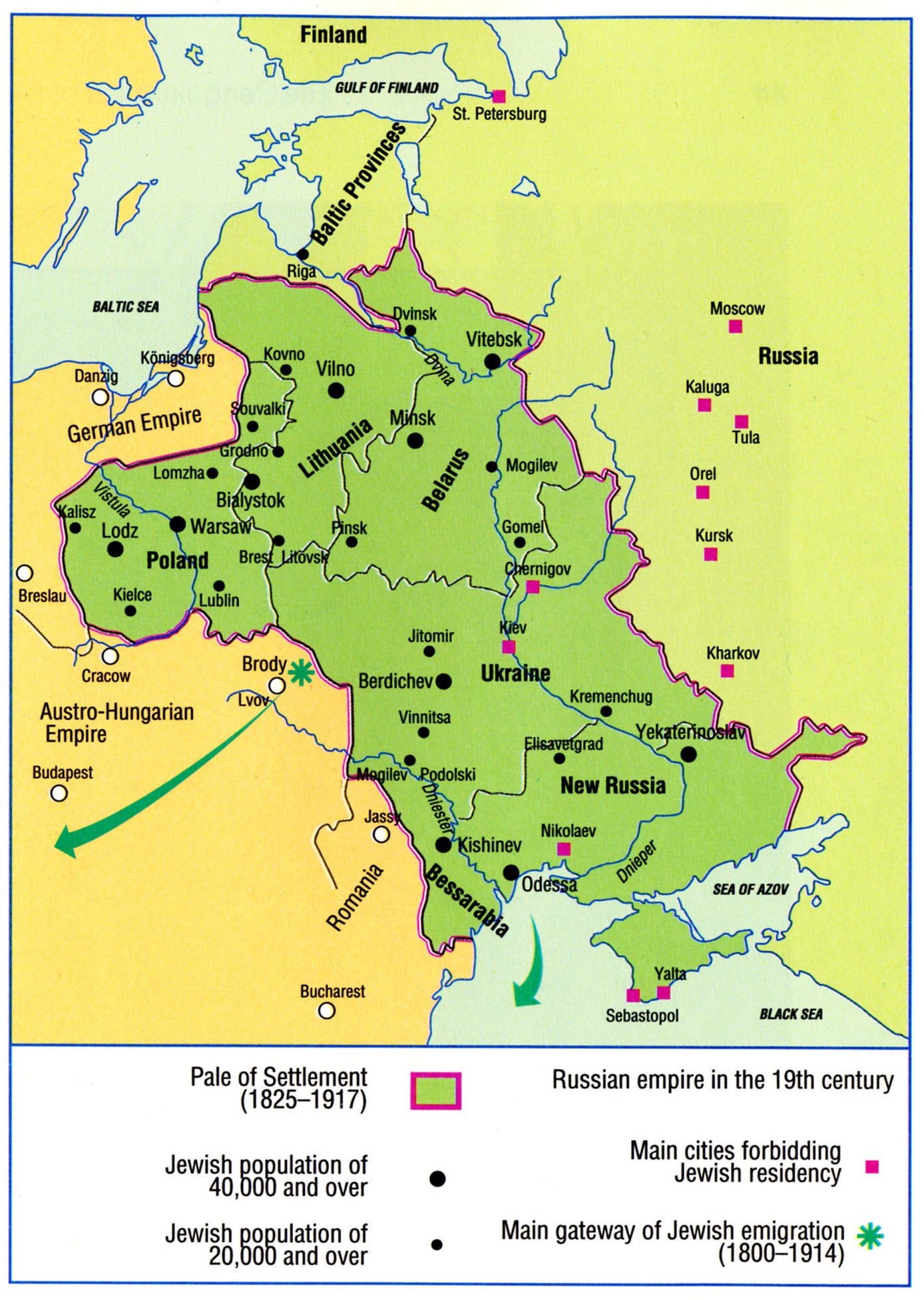

By their fruits you shall know them. And the Russky lands boast of vast fields of rich wheat and tares both. When adopting an historical perspective, however, the tares always appear to win out in the end — an appearance effected by the horizontal perspective, no doubt, but let’s see what events look like on this plane. The events of the 17th-century reunification of the Russias culminated with the ascent of Peter the Great and the founding of Russia as a German-style Empire, sidelining the Church and baptizing the whole structure of authority in dialectical efficiency. The new Russian Empire, especially once it expanded westward into Polish territory, hosted the largest population of Judeans in the world, but by the end of the 18th century Empress Catherine the Great, that secularizing devotee of the Enlightenment and enemy of the Church’s spiritual life, created the Pale of Settlement to which Judeans would be restricted. The Pale encompassed the western parts of the Empire, modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Poland, and persisted in various shapes through the end of World War I. Sometimes Judeans there were not allowed to farm or live in major cities. Poverty was the ironclad rule among them, but in the villages called shtetls where they commonly lived, a Yiddish culture thrived nonetheless.

The 19th century saw the rise of Western-influenced dialectical hermeneutics in all Russian territories, including “I am not you” nationalism, revolutionary activity, and antisemitism. Ukrainian national identity, in opposition to Little Russian identity, put down roots that persist to this day. Dialectical materialists of the socialist bent scored a breakthrough accomplishment when in 1881 they assassinated Tsar Alexander II, ironically cutting short the most liberal reign of the century and inciting the reactionary counter-reforms of Alexander III (or it would be ironic if that weren’t exactly how dialectic works). The assassination unfortunately precipitated an eruption of antisemitic pogroms among Orthodox Christians across Little Russia. Dozens of Judeans were killed, hundreds of Judean women raped, and countless Judean homes destroyed. From the relative safety of Great Russia, the tsar responded by punishing the Judean communities with harsher restrictions. The violence set the tone for the next forty years of imperial decline, particularly deadly pogroms breaking out from 1903–1906, precisely when revolutionary activity was heating up and constitutional reforms were adopted. This violence against Judeans was concentrated in the southern lands of burgeoning Ukrainian identity. Of course they weren’t going to happen in Great Russia — Judean communities were forbidden by law from forming there.

The Orthodox Church in the Russian Empire at this time was deprived of its patriarchal authority and reduced to a ministry of the state. Besides the synod of bishops there was a non-clerical government minister assigned to overlook the Church. From 1880 to 1905 that man was Konstantin Pobedonostsev, who was vocally opposed to all Western influence and customs, but in a dialectical way that was entirely in keeping with the conservative half of Western polarity. He as a matter of church policy used dialectical opposition to non-Christian peoples, prominently Judeans, to prop up Orthodox Christian identity for nationalistic purposes. One can only imagine how this man in charge of the Church must have interpreted her prayers during the holiest time of year.

On Holy Thursday, at the Compline Canon, Ode 8, we read,

‘Let Jesus Christ be crucified,’ cried the Hebrew people together with the priests and scribes. O faithless people! What evil has He done, He who raised up Lazarus from the tomb and wondrously has brought to pass the salvation of all?

The lawless people cried aloud before the judgment-seat of Pilate: ‘Crucify Him, and set free for us Barabbas the murderer who lies bound. Scourge Christ and take, O take Him and crucify Him with the evildoers.5

Then at Ode 9, in the context of the back and forth between Pilate and the crowd demanding Christ’s crucifixion, there’s this:

O lawless Judeans! O people without understanding! Do ye not remember how many miracles of healing Christ performed for you? Do ye not comprehend His divine power, just as your fathers before you understood it not!6

Again, the Judeans are you. By their “fathers” understand their preceding types. Their preceding types are your preceding types. These sins which historically happened and are described accurately in the Gospels, as also in the church services based on the Gospels, are yet presented to us in narrative form for our interpretation. Are we sensitive to our transgressions against Love, and do we interpret the world accordingly, taking blame upon ourselves and excusing all others? Or do we indulge in the highmindedness deserving of Bolshevik decimation?

The service of the Twelve Gospels held on Holy Thursday evening (Matins for Holy Friday) are particularly rife with traps targeting antisemites. In Antiphon 6, we pray:

Today the Judeans nailed to the Cross the Lord who divided the sea with a rod and led them through the wilderness. Today they pierced with a lance the side of Him who for their sake smote Egypt with plagues. They gave Him gall to drink, who rained down manna on them for food.7

At Antiphon 12:

O lawgivers of Israel, ye Judeans and Pharisees, the company of the apostles cries aloud to you: Behold the Temple that ye have destroyed; behold the Lamb that ye have crucified. Ye gave Him over to the tomb, but by His own power He has risen again. Be not deceived, ye Judeans: for this is He who saved you in the sea and fed you in the wilderness. He is the Life and Light and Peace of the world.8

Crucifixion is not a Judean form of execution; stoning is. Crucifixion is the Roman form of execution. Yet these verses are prayed in the midst of reading all the Gospel accounts of the Passion. They are not deceived as to how the events transpired. The Judeans represent the best of us, and they are held responsible for using Roman law by way of false witness to achieve their wayward intentions. That is how the story goes.

Antiphon 13:

The assembly of the Judeans besought Pilate to crucify Thee, O Lord. For though they found no guilt in Thee, they released Barabbas the malefactor and condemned Thee the Righteous; and so they incurred the guilt of murder. But give them, O Lord, their reward, for they devised vain things against Thee.9

Advocating for sinners to receive their reward is a pattern of prayer drawn straight from the Hebrew Psalms (passim). This verse is to be read anagogically by Christians no less than the Psalter is. That the condemnation is to be directed inwardly is indicated already in Psalm 7: “O Lord my God, if I have done this, if there be injustice in my hands, if I have paid back evil to them that rendered evil unto me, then let me fall back empty from mine enemies. Then let the enemy pursue my soul, and take it, and let him tread down my life into the earth, and my glory let him bring down into the dust.” The self is not spared for those whose desire above all is that God’s will be done on this earth. That’s what great love dictates. Howbeit the punishment (e.g., Babylonian exile, or Bolshevik decimation) is not understood to be retributive in aim but rehabilitative, should the will of those punished ever come around to join this purpose. (Resurrected Russia, like the Second Temple, seems still to be awaiting the glory of God, even as Herod the Great builds up the church.) In such dire cases, it is desired that the flesh be given over to destruction, that the spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord Jesus (1 Cor. 5:5).

But the hits from Holy Friday Matins keep coming. Here’s one from among the stichera at the Beatitudes after the Antiphons — it actually occurs directly after “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy”:

The murderers of God, the lawless nation of the Judeans, cried to Pilate in their madness, saying, ‘Crucify the innocent Christ’; and they asked rather for Barabbas. But with the words of the good thief we cry to Him: Remember us also, Saviour, in Thy Kingdom.10

Hermeneutically gruelling, isn’t it? This is the Passion of the Christ. It’s meant to be. The moral dissonance between “Blessed are the merciful,” preached in peace by Jesus from a mountaintop, and the extreme mercilessness shown Him in Jerusalem is intentional. Later, at Canon Ode 9:

The destructive band of evil men, hateful to heaven, the synagogue of the murderers of God, drew near to Thee, O Christ, and as a malefactor they led Thee away, who art the Creator of all. Thee do we magnify.

Ignorant of the Law in their iniquity, studying the words of the prophets in vain and to no purpose, unjustly they led Thee, the Master of all, as a lamb to the slaughter. Thee do we magnify.

Moved by jealous wickedness, the priests and scribes took Him who is by nature Life and Life-giver, and they delivered Him to the Gentiles to be put to death. Him do we magnify.11

You’ve read this article all the way to this point; you’ve already been shown the difference between the anagogical and the dialectical readings of such texts. You should know the difference, and know which reading to pursue and which reading to dismiss. Yet if you’re like me, and I’m the one writing this even, it’s hard to keep one’s understanding anagogical! The way we perceive the text is a function of how much purification our mind’s eye has undergone. The stomach churns of any humanist who reads these lines (“‘Murderers of God’? Really?”), tragically blind both to these words’ immense spiritual utility and to humanism’s own debased hermeneutic being the cause of the discomfort. Insofar as we ourselves are humanists, preferring our own pride to God’s humility, we too will struggle to see the manifest love and mercy in these lines. For the hesychastic Christian, however, it is clear that these verses are offering a symbolic roadmap to perfect love of God and neighbor.

For example, let’s backtrack to Antiphon 12:

Thus says the Lord to the Judeans: ‘O My people, what have I done unto thee? Or wherein have I wearied thee? I gave light to thy blind and cleansed thy lepers, I raised up the man who lay upon his bed. O My people, what have I done unto thee, and how hast thou repaid me? Instead of manna thou hast given Me gall, instead of water vinegar; instead of loving Me, thou hast nailed Me to the Cross. I can endure no more. I shall call My Gentiles and they shall glorify Me with the Father and the Spirit; and I shall bestow on them eternal life.12

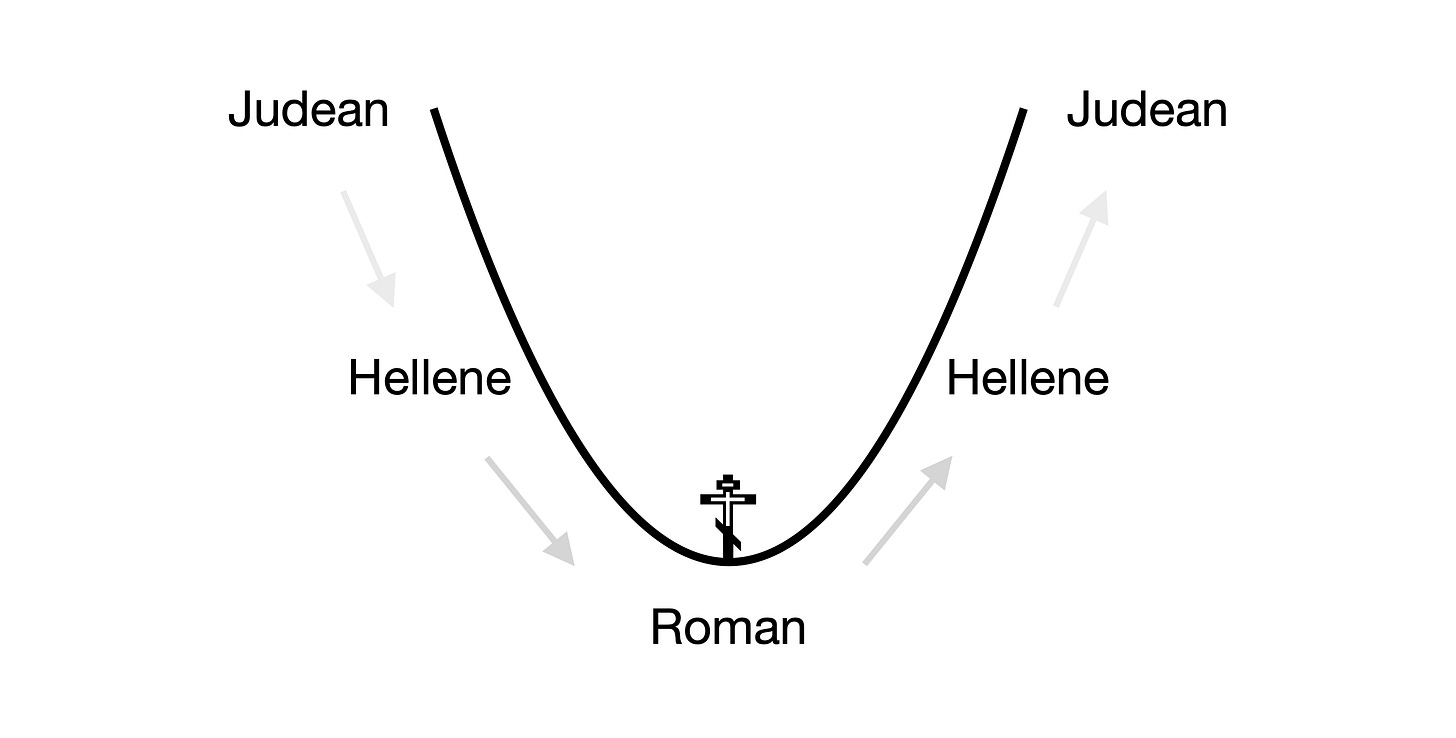

If, anagogically, the Judeans are the image of God in me, that which distinguishes me from the animals, I can learn here from my failure how to take accountability for all evil and attribute all good to the incarnate God. Scripture indeed may teach us many useful things about ourselves, but we should never forget it is primarily about Christ. So in the Incarnation of God we see death-defying, life-bestowing grace imbuing the flesh in a way that hadn’t been done before. That’s what the call of the Gentiles can be seen to signify. The Gentiles represent the flesh as well as the lower passions of the soul associated with the flesh: the Romans (flesh) and Hellenes (soul passions), respectively. Recall that the sign placed on the Cross announcing the King of the Judeans was written in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, encompassing symbolically body, soul, and spirit (that which is Roman, that which is Hellenic, and that which crosses over). The Son of God comes to us in a body, with the passions of the soul in blameless perfection, conquering both death and sin. Likewise the Church comes to us in Roman body, Hellenic soul — and, if we look in the heart of the Church, Judean spirit. In “Bodies and Souls” I drew this diagram to explain the process of how redemption is made real in our lives:

Perhaps also we can see in salvation history the following rendition of the same:

In the expansion of kinship with God beyond the Judeans to include the Gentiles, we see an image of the Incarnation, of God’s “enfleshment”. That the Judeans did not go along with the expansion is emblematic of the spiritual barrenness afflicting all mankind, thus necessitating the divine condescension. The spiritual solution, as I traced out in “Bodies and Souls,” is for the body to be trained in spiritual patterns so that the body’s stability in virtue can then train the wayward soul in the more difficult virtues that eventually refer back to Spirit. Only once Christ conquers the death of the body at the bottom of this arc, can we finally learn how to resurrect our soul from the passions and be deified by the Spirit. And so grace having first rested on the Judeans — so that we fallen humans drunk on knowledge can come to know the difference between our lowly selves and Almighty God — it then crosses over to the Gentiles, so that we can also know the gratuitous mercy of God in His unfathomable loving union with us. But the point after all this is not for us to remain in the stubborn, unworthy condition in which we were found. Having been shown the gratuitous mercy present in the resurrection of the flesh, we are to be resurrected in all three aspects of our soul, testifying in our lives that Christ frees us from sin as well as from death. Then, even nature is overcome in our crossing over into perichoretic union with God the Holy Spirit, the very breath of God by which the world was spoken into being.

This way the spiritual barrenness in us, which we read about in Judean history, is in the end cured. There’s a fractal pattern here; it’s abundantly evident in narrative miniature in Christ’s resurrection from the dead, in the reassembly of the dispersed disciples, in the conversion of the brute Gentiles — the folds keep getting wider. We would expect the fold tracing the journey of the Judeans to be the widest yet. It’s not hard to imagine Paul’s prayers for his kinsmen according to the flesh (in Rom. 9–11) indeed coming to fruition. That’s especially so given the typological resemblance of Gentile history in the New Covenant to Judean history in the Old. Maybe the former will culminate with a transferral of grace not unlike the latter. We’re already told by the Prophets (Ezekiel, Zechariah, John) all history ends in the establishment of the New Jerusalem and a roll call of all Israel, omitting only the tribe of Dan (cf. Rev. 7:1–8), historically associated with the Hellenes.13 Revelation at least seems to confirm a chiastic flip back to an affirmation of the original Judean-centered symbolism of Israel, a symbolism in which all humans are called to participate, which indeed never went away because it’s a fractal pattern, present in all things. What more can be said? The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards Judeans — and with them, all Israel.

From the Aposticha at Matins for Wednesday of the Sixth Week of Great Lent. The Lenten Triodion Supplement, td. by Mother Mary and Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia (St Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 2007), p. 288.

From the Aposticha at Vespers for Palm Sunday. The Lenten Triodion, td. by Mother Mary and Archimandrite Kallistos Ware (St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 2002), p. 492.

From the Praises at Matins for Palm Sunday. Ibid., p. 501.

From Canon Ode 1 at Matins for Palm Sunday. Ibid., p. 496.

From Canon Ode 8 at the Compline Canon for Holy Thursday. Ibid., p. 562.

From Canon Ode 9 at the Compline Canon for Holy Thursday. Ibid., p. 564.

From Antiphon 6 at Matins for Holy Friday. Ibid., p. 577.

From Antiphon 12 at Matins for Holy Friday. Ibid., p. 584.

From Antiphon 13 at Matins for Holy Friday. Ibid., p. 586.

From the Beatitude verses at Matins for Holy Friday. Ibid., p. 589.

From Canon Ode 9 at Matins for Holy Friday. Ibid., p. 595.

From Antiphon 12 at Matins for Holy Friday. Ibid., p. 583.

See Philippe Bohstrom, “Tribe of Dan: Sons of Israel, or of Greek Mercenaries Hired by Egypt?,” Haaretz, 4 December 2016. I wanted to give a citation for this association, knowledge of which I’ve absorbed from various disremembered sources over the years, and this was the first item that turned up on a Google search. It’s decent enough.