In Parts 1 and 2, we covered the whole chiastic base of U.S. political history from alpha to omega. Now the octave ascends to its conclusion in a triadic process we are still in the midst of.

Ϛ. The Sixth Party System (1980–ca. now)

Red State v. Blue State

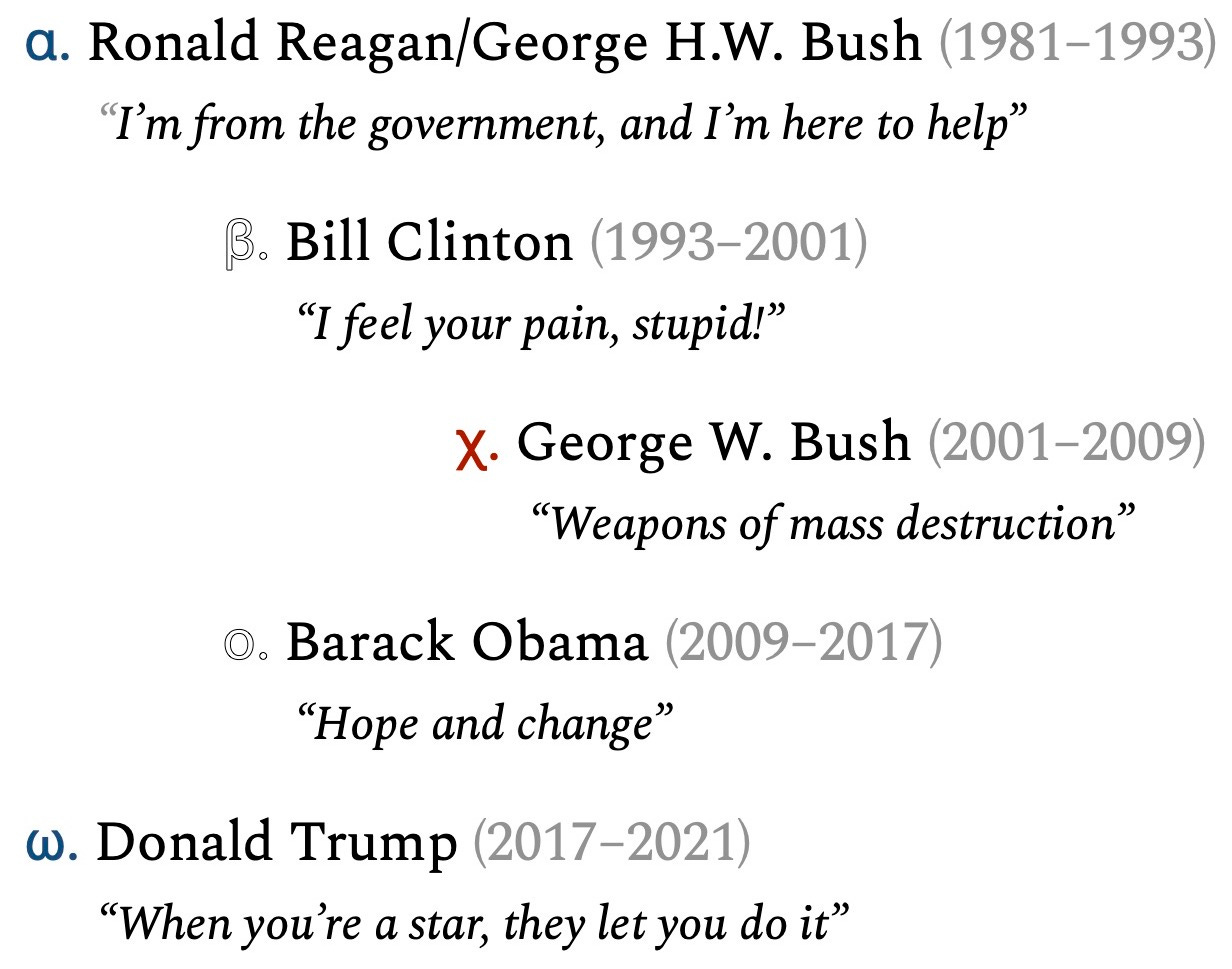

Though it’s always been true, when I wrote “The dialectic of Western politics is patterned after the corruptive polarity of desire and anger, and it’s killing us,” I especially had our most recent party system in mind — the one in which I’ve spent my whole life. What I have to say about the brand of political polarization that erupted first of all with President Ronald Reagan and his conservative opposition to big government (but not at the expense of big military) I have already said in that piece, and I’m not interested in detailing here the history of the past four decades the way I did for prior party systems. The story of Enlightenment reason triumphing in American statecraft like a new god on earth has ended for now. The lower passions of thymos on the right and epithymia on the left have overthrown reason. Once that revolution happens, it’s very hard to tell the succeeding story in detail because, the poles being contained within each other, none of it makes any rational sense.

What does interest me greatly here is how the revolution happens, how the eruption of this polarization — out of the Fifth Party System, which was highly depolarized — came about. And when did it happen? Where do you draw the chapter break between the Fifth and the Sixth Party Systems? There’s general consensus around when the previous realignments occurred. The years 1824, 1896, and 1932 are uncontroversial. In the 1850s, things got a little chaotic when the Whigs crashed and burned, and the consensus as to where the line is drawn between the Second and Third Party Systems is a bit fuzzy, but not too much. The line between the Fifth Party System and the Sixth, however, varies greatly depending on whom you’re asking. A key component of the realignment is the conversion of the South from the Democrats to the Republicans, for example. That can first be seen to happen with Barry Goldwater’s campaign in 1964, the same year as the Civil Rights Act. Some would point to the realignment occurring as early as that. But Goldwater’s campaign was an abject failure, a conservative opposition to New Deal bureaucracy that the Republicans wouldn’t try again until Reagan in ’80. The South, meanwhile, voted for a Democratic president as recently as Jimmy Carter in ’76. With Reagan, the burgeoning Evangelical vote swung right, and things really changed.

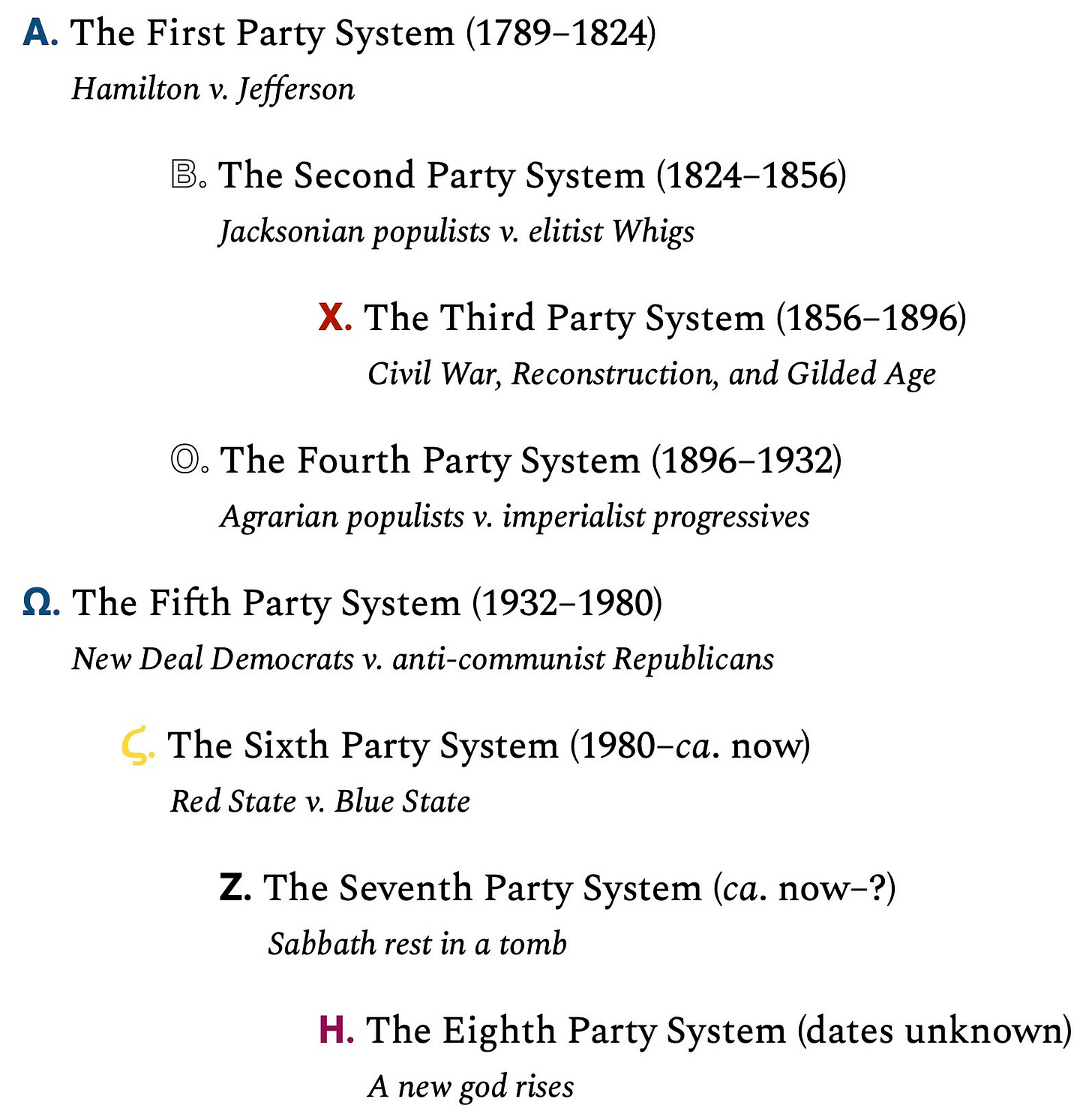

The Republicans finally going conservative in the style of William F. Buckley, Jr. was only part of the realignment, however. It is extremely interesting how, late in the Fifth Party System (as I identify it), the dialectical process of U.S. history began to become conscious of itself. The whole idea of party systems and realignments had been around for a while, but the idea made new headway in 1967 with the publication of The American Party Systems: Stages of Political Development, an anthology of articles by historians and political scientists edited by William Nisbet Chambers and Walter Dean Burnham. A second edition with an additional chapter was published in 1975. President Nixon himself imagined he ruled at a turning point in history and was the engineer of a new realignment. You can find some whose views agree with that assessment, pointing to a break between party systems either at the beginning or end of his presidency. But I don’t see the once–vice president under Eisenhower being all that different a Republican in regard to New Deal–era politics. Nor do I think his presidency comprises the realignment that occurs when the history of party systems becomes conscious of itself (Nixon was just conceited).

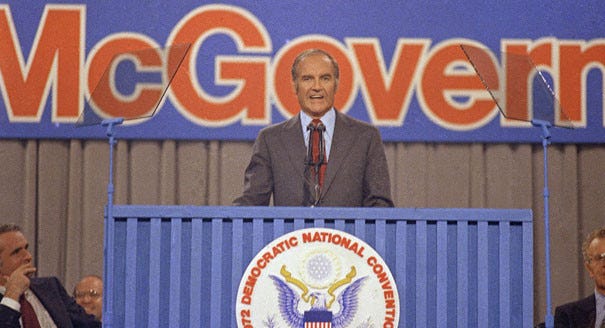

The key to what that looks like, and how the parties realigned so as to embody polarization instead of frustrate it, is something I found in a 2015 book by John S. Jackson, The American Political Party System: Continuity and Change over Ten Presidential Elections. Jackson tracks the changes that occurred in the presidential nomination process of both parties beginning in 1970. That’s when the Democrats, deeply wounded by the political disaster of their 1968 election cycle, empowered a so-called Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection, also known as the McGovern–Fraser Commission (after the congressmen who chaired it), to change the way presidential nominees are chosen. In 1968, Vice President Hubert Humphrey only entered the race once President Johnson dropped out of it unexpectedly after the first primary election. Humphrey entered no primary elections. But he won the nomination at the Democratic National Convention anyway because there the delegates got to decide who to nominate, and the way the delegates were chosen favored powerful insiders who resisted change (whereas primary voters overwhelmingly favored anti-war candidates, which wasn’t Humphrey). The McGovern–Fraser Commission began a trend, much tinkered with through the years, that gave more power to primary elections and radically altered how delegates were chosen so that by means of affirmative action those historically underrepresented, namely women and minorities, would be given greater say in who was nominated.

This was another populist movement, like the ones the Second and Fourth Party Systems hinged on, except that for once, the realignment was occurring based not around how to govern the country, but around how to govern the party. This is what I think it looks like when actors fighting for power in the history of party systems become self-aware that that’s what they are. And then when a representative democracy becomes more populist on the level of party, polarization of the two lower passions, each party conforming to their respective passion, is going to overcome all reason.

The first beneficiaries of the changes in the Democratic party were Senator George McGovern in ’72 (yes, the guy that chaired the commission) and Governor Jimmy Carter in ’76. I covered the downsides of their nominations, how sidelining the insiders proved counterproductive in choosing electable candidates who could effectively lead, in the previous chapter. All these changes the Democrats made eventually dragged the Republican party in the same populist direction (sans as much affirmative action) on account of the primary system being complexly interwoven between not just the two national parties but also a plurality of states jockeying for national influence. For all these reasons, some spectators of history date the realignment of the Sixth Party System to some time in the seventies, before the triumph of Reagan. I gave a lot of consideration to these earlier dates. But I look at the fruits of making the nomination process more populist, less elite-driven, and I see them as unleashing the polarized lower passions from the control of reason. Carter, in all his feeble moralism, was still fighting against this. No, that polarization doesn’t erupt, creating a break with the past, until the 1980 election, when Carter and Kennedy’s antagonism spoiled the Democratic National Convention, and a former B-list Hollywood liberal who converted to conservatism in the time of Goldwater finally arrived.

Looking deeply, trying to figure this out, I think has given me greater insight into realignments of the past. In 1896, which everyone agrees upon as a threshold, everything turned on the Democrats’ embrace of bimetallism, but the issue was commonplace throughout the back half of the previous system; it just hadn’t been harnessed. The same thing happened with the Republicans and abolitionism in the 1850s. The election of FDR in 1932, moreover, is clearly a realignment. Yet Hoover himself had tried many New Deal–like programs just not on the same scale, and Franklin Roosevelt took much inspiration from the progressivism of Woodrow Wilson and distant cousin Teddy. That by 1980 affirmative action–fueled populist reforms of the nomination process, combined with the rise of Buckley-style conservatism, brought about a political realignment need not necessarily mean that that realignment should be dated to the beginning of those developments.

All this reasoning I had in place before looking for internal structures to any of the party systems. I did not anticipate that there would be any coherent internal structures to the party systems. As it happened, the dates I chose yielded neat chiasmi like I had for the Fifth Party System, concluding with Carter, and like I have here:

Now, this is a very coherent forty-year structure, yet as I sit here at the end of 2023, it is not at all evident that the Trump era is over. He has not gone away, and is the presumptive favorite to win the presidency again in 2024, even as he faces a growing mound of unprecedented legal challenges. Just a couple days ago, four state justices in Colorado ruled Trump was ineligible for their state ballot for reasons of insurrection (something he hasn’t been convicted of by any court; in fact the Senate acquitted him of this upon his second impeachment trial). By election day next year... who knows? We could be choosing between one candidate locked in prison and one candidate buried in a grave. And the identity of those candidates might be the reverse of what you’d expect! Is the Trump era over? For now it suffices to admit that realignments aren’t discernible with precision when you’re living through them, not to schlubs like me. This outline is provisional. (I feel weirdly confident about it, though.)

It all begins with Reagan and the era of deregulation that he started, which in terms of banking and finance was to persist throughout the party system. The ’80s were a time of yuppies, patriotic enthusiasm, aerobics in leotards, AIDS, crack cocaine, Evangelical Christianity, blockbuster entertainment, ever rising crime rates, Satanic panic, insider trading, the collapse of unions, and illegal arms dealing — “Morning in America”, as Reagan’s ’84 re-election campaign called it. It was also a time when an empire buckled and collapsed under the weight of gerontocracy, overlong war in Afghanistan, and inability to feed itself. Only on this side of history, it was the Soviet Union. The Cold War ended (ostensibly), and the United States was the last superpower standing. Bush Sr., who had been added to Reagan’s ticket as a compromise with the establishment Republicans of the previous era, rode Reagan’s coattails in ’88 but couldn’t fit the Reaganist mold, promising no new taxes, but failing to deliver due to a recession induced by Reagan’s deregulation and trickle-down economics.

Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas won next, in 1992, overcoming the scandal of an adulterous affair on his way to the Democratic nomination. Clinton was an adulterous man, and he would adulterate anything to get what pleased him. In the midst of a recession, his lead campaign strategist said, “It’s the ecomony, stupid!”, while the candidate himself shouted, “I feel your pain!” This epithymetic persona, skilled in the ways of seduction, had what it took to woo a Reaganite America suffering an economic downturn:

But he could take that epithymetic empathy and whip it around like an aggressive thymic weapon, as at a New York City campaign event where he turned on AIDS activist Bob Rafsky, who had been heckling him from the crowd in order to bring attention to the disease he was dying from:

The poles are contained within each other, and Clinton was a master of both. But his epithymetic approach to power opened a door for the powers of thymos to align against him. The so-called Republican Revolution that occurred in the mid-term elections of 1994 entrenched the polarized political realignment on the congressional level, and the legislative battles, ethical scandals, sex scandals, and impeachment trial that ensued revealed the true meaning of the Sixth Party System. It’s epithymia vs. thymos, desire vs. anger, appetite vs. control, entitlement vs. force, greed vs. tyranny.

The 2000 election was split down the middle like a bar magnet, with the state of Florida dangling from the nation’s body like chad from a hole punch. It was the first election in which I voted, and for the life of me, I couldn’t tell the difference between the parties — I hadn’t yet realized the relevance of tripartite psychology. Not that that would have helped me pick a candidate! Reminiscent of 1824 when the House of Representatives chose the president, or 1876 when a back room deal did, in the year 2000 the Supreme Court in effect decided the results of the election by stopping a recount in Florida. Republican Governor of Texas George W. Bush, son of H.W., was the beneficiary. With a cabinet of thymic all-stars for the ages, Bush waged the unethical, mendacious, and hypocritical “War on Terror” on which the Sixth Party System pivots — a real boon for the military–industrial complex and surveillance state alike.

The 2004 presidential election was largely seen as a referendum on what were being identified as the culture wars — the polarization of desire and anger on the political stage. Days before the election, fugitive arch-terrorist Osama bin Laden surfaced in a video taunting Bush. So did that hurt Bush in the polls? No, it stoked voters’ thymos, which helped the candidate who recapitulated thymos. The day after Bush’s victory, liberal Daily Show host Jon Stewart chalked the Democrats’ loss up to disgust with “the idea of two dudes kissing,” as on the sitcom Will & Grace. Translation: epithymia lost.

America did a lot of the losing in Bush’s second term, first with Hurricane Katrina wrecking New Orleans in 2005, exacerbated by poor federal response, and then in the financial collapse of 2007–8, wherein rampant reckless greed on the part of financial institutions instigated the Great Recession, the greatest economic crisis since the Depression. It all happened under Bush’s watch, but it’s attributable to the whole Reaganite legacy of deregulation (and corporate capture of regulatory agencies). A key factor in the financial collapse, for example, was a Republican bill signed by President Clinton in 1999 that repealed parts of the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933 restricting banks from risky behavior. With the economy in ruins, entrenched in two intractable, unwinnable wars, having unleashed the dystopic powers of the surveillance state plus the “enhanced interrogation” techniques of the War on Terror, George W. Bush ended his time in the White House as what must be the single worst president in U.S. history.

And yet the guy slew AIDS! Reagan could hardly be goaded to mention it. Clinton had to be heckled into caring about it. But it was George W. Bush who, in 2003, with initiative and conviction, instituted the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has since diffused the AIDS crisis and saved dozens of millions of lives worldwide, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. The worst president ever did that. I told you none of this will make rational sense.

So the United States swung wildly from one pole to another. What could I possibly say about the presidency of Barack Obama that won’t set on fire the hair of at least half my potential readers? On account of how deeply polarized we are, even those like myself who strive not to be, it is very difficult for us to think and communicate rationally about that which is designed to thwart all rationality. I will point out that this is where, in opposition to Bush’s thymos, the term progressive is redefined by the epithymetic left to mean something substantially different from what it used to mean in U.S. politics. In the early twentieth century, in the era of Teddy Roosevelt, progressivism was the domain of Republicans, heirs to the legacy of abolitionism, those who sought to control the appetitive excess of capitalistic society by rationalist means in cooperation with those religious morals deemed rational. The aim of progressivism was the rational reform of the lower passions. For instance, a goal was the establishment of family values, as determined by the remnants of the Christian faith that survived the Enlightenment, in the face of passions of desire and anger that would corrupt them. Progressives of our own century, however, harness the justification of epithymetic desires in opposition to thymic tyranny, and redefine rationalist progress along those partisan lines, their reason being enslaved by their desire. Hence, as an illustration, American progressivism of the original variety resulted in the prohibition of alcohol (the consumption of which in that era was way out of hand by any objective measure), whereas contrarily, American progressivism of this century has resulted in the legalization of marijuana (in many states, if not federally, yet).

So we have this new progressive agenda motivating politics on the left, but on the right we have an agenda consisting of, well, nothing more than stopping epithymetic policies and gaining and maintaining thymic power. (Again, I’ve written about this previously.) The rise of the Tea Party in the mid-term elections of Obama’s first term mirrored the Republican Revolution that afflicted Clinton’s presidency, but the differences between the two situations are revealing. In ’94, rising House leaders Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey — whose names have to be mentioned, sure, for their historical importance, but also so that authors who would name villains in sci‑fi/fantasy novels can receive the affirmation from reality that they need in order to go full out and not hold back — rising House leaders Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey provided their thymic rebuke to the President’s epithymetic approach to power in the form of a “Contract with America,” a legislative agenda based in Reaganist principles. Indeed Clinton fought them, but also found ways to compromise with them in taking apart pieces of New Deal legislation, as with a welfare reform act of 1996, allowing states to place work requirements on recipients of government assistance and limit how long they could receive it. Clinton, after all, was an adulterer; compromise was possible with him. He tried promoting his wife’s ideas for a new national healthcare program, but it was not in the congressional Republicans’ interest for him to remain faithful to his wife. In truth, overall, Clinton was not ashamed to adopt Reaganism in order to win elections in a Reaganist country. He supported gay rights, but instituted a “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy in the military and signed a Republican bill allowing states not to recognize gay marriages from other states. He created tough-on-crime policies (not white collar crime, of course), starting even before the Republican Revolution, as a response to conservative critics, greatly increasing incarceration rates over the course of his presidency. As mentioned previously, he balanced the budget and repealed key financial regulations on banks, all at Republican prompting.

Obama, in contrast to Clinton, was (and is) a man of unimpeachable family life. Compromise was not going to characterize his response to the Tea Party, but then I don’t know that there was anything there to compromise with. If the Tea Party expected Obama to be as accommodating to them as Clinton was to the Republican Revolution, well, the political context just wasn’t there. Though they both left recessions in their wake, Bush Jr.’s legacy in the 2010s was certainly not what Reagan’s legacy was in the ’90s. A line had been crossed, and polarization was now a pandemic disease corroding all political operations. If Obama’s response to the financial institutions and regulatory agencies responsible for the Great Recession was underwhelming in scope and harshness, especially coming from the candidate of hope and change, then this at least was a testament to the abiding legacy of Reaganist economics abetting the pattern of polarization. And if Obama only expanded the surveillance programs begun under the auspices of his predecessor’s War on Terror, which after the disposal of Osama bin Laden were destined to turn inward on perceived internal threats, then this is merely proof that the powers of polarization can in fact work together — if, that is, the objective is to overthrow the United States’ original reason for existence, and with it, reason altogether.

After the 2010 sequel to the Republican Revolution, the stated objective of the Republicans in control of congress was to prevent Obama from winning a second term. They failed. More bad-faith acrimony followed. Combative lies were spread that were worthy of the old battle between Adams and Jefferson in 1800. But the reason for the country’s existence grew fainter and fainter from vision. A populist dialectical reaction ensued that only accelerated the nation’s demise by polarization. The elitist-driven media’s dialectical reaction to the populist reaction has induced a state of derangement poisoning the wells of information even more strongly than before.

But the situation’s not changed: the poles are still contained within each other. Consider pizzagate, if you will, the 2016 online conspiracy theory centered around a D.C. pizza parlor.

Just as the left commonly accuses the right of abuses of thymic power that the left themselves perpetrate for the sake of desire (misinformation, conspiracy theories, election meddling, etc.), I can only imagine the reason the QAnon crowd and those adjacent to them on the right are so obsessed with persecuting pedophilia is because they themselves, on account of their thymic overdrive, are prey to this form of epithymetic temptation. And good on them for getting after it; I hope they succeed in their persecution. But I wouldn’t call using rifle blasts to search a pizza parlor without a basement — because you’re convinced Hillary Clinton is running a pedophilia ring in the basement — “succeeding”. I would call that unhinged mania, the pole sharing an axis with the very perversion of desire you’re trying to persecute. I would call that giving the political left excuse to overlook crimes of desire like pedophilia and sex trafficking, ensuring these things have political shade in which to thrive....

This last aspect is a little conspicuous, though, right? The December 2016 incident of violence to which I refer is so blatantly counterproductive to the right-wing cause (while also being conveniently bloodless) as to be easily suspected as a false flag operation. Indeed it is so suspected. People are so twisted in their minds these days, and outrage on the left or the right is so easy to manipulate, you can’t rule out the existence of false flag operations — but people are so stupidly prone to the polarity of their passions these days, no single incident could ever be assumed to be a false flag operation, no matter how idiotic. Our behavior all-around really is that self-defeating. In every way that we engage with the polarity of desire and anger, no matter which pole we cling to, we’re thwarting our causes and killing ourselves.

With the Sixth Party System, the American Revolution has collapsed within itself. Neither the authorities nor the rebellion are worthy of anybody’s trust. Many still are only willing to see one half of the mendacity, and cling to the other side with a dubious faith. “When you’re a star,” as it’s said, “they let you do it.” Those who see both sides of the lie, meanwhile, trust in themselves instead and are just as foolish — possibly even more so. Our own passions have us cornered. Politically, it’s checkmate.

Ζ. The Seventh Party System (ca. now–?)

Sabbath rest in a tomb

As I’ve explained a few times in a few places, the threefold symbolism of stigma–zeta–eta that I employ traces the pattern of Crucifixion, Death, and Resurrection that occurs symbolically on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday — the day of preparation, the sabbath, and the Lord’s day; or the sixth, seventh, and eighth days of the week (Ϛ, Ζ, and Η are the Greek numerals for 6, 7, and 8). In the spiritual life this pattern is experienced as purification, illumination, and perfection, according to such Church Fathers as St. Dionysius the Areopagite and St. Maximus the Confessor.

As with the fivefold chiasmus, this pattern appears in a multitude of contexts, not all of them holy or good. It is fundamentally a pattern of creation, and like the rest of creation can be put to perverted use by souls endowed with free will. The modes of symbolism in which you’ll find the pattern can be positive or negative, Christian or antichristian. I’m at the disadvantage in this grand narrative of not having already demonstrated the octave structure in Scripture, liturgics, and elsewhere, so I can’t expect my readers to have all the contextual background from which I’m operating. But let me share one passage in Scripture that I think will be found both helpful and relevant to the topic at hand.

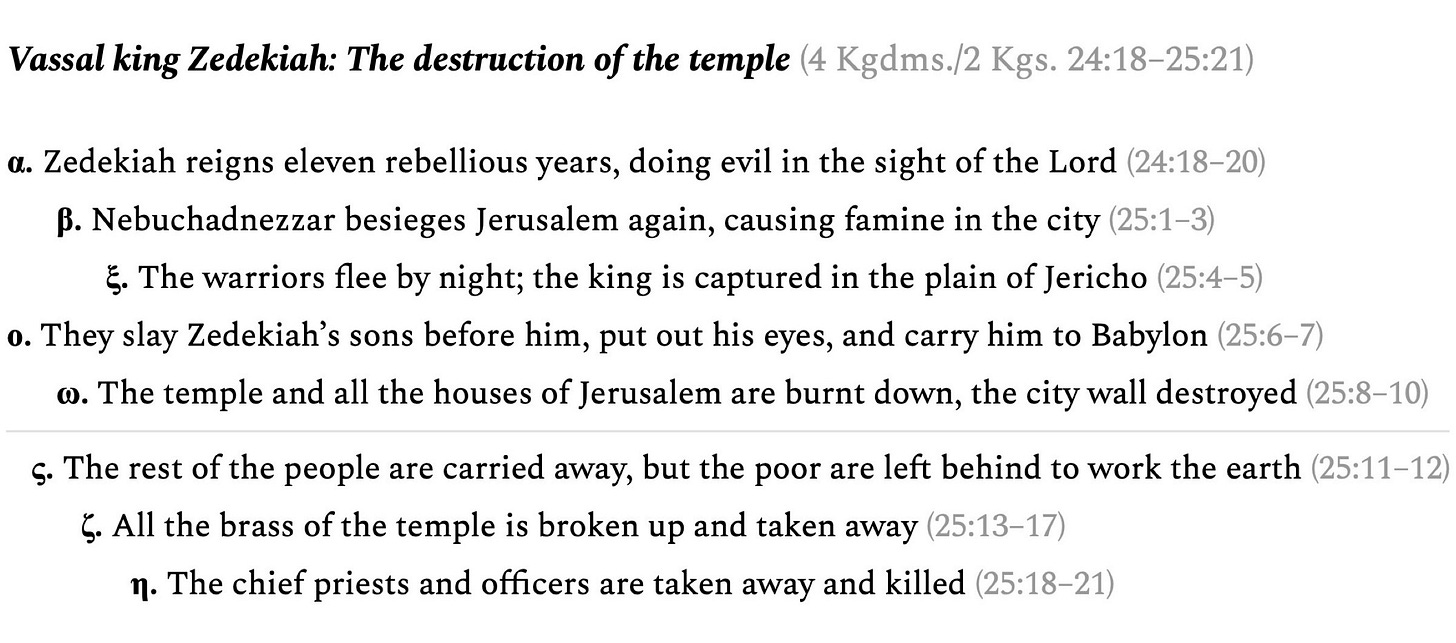

At the end of 4 Kingdoms (2 Kings), the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple is related in the course of the reign of the vassal king Zedekiah. This is the nadir of sacred history before the crucifixion of the Messiah; everything holy is desecrated. Now, each of the books of Kingdoms is in octave shape, and the octave appears in many fractal layers as well. This passage is in octave shape, except each element is a desecration of its potential theme.

The first five items take the form of a cosmic ksiasmus (again, see “The Cosmic Chiasmus” for clarification). First (α.) the king’s reign is established, but in evil not in good. Then (β.) instead of an exodus from death, there’s an exile from life; ironically the Judeans can’t even escape their location, and Jerusalem is turned into a breadless prison. Centrally (ξ.), instead of making expiatory sacrifice, the warriors flee, and the king is captured shamefully not in the heights of Jerusalem, but in the lowly plain of Jericho, symbolic of sin. Fourthly (ο.), in the place where we would like to see fruitfulness and the assimilation of virtue, instead the king’s children are killed, his eyes are blinded, and he’s carried off to Babylon. Lastly (ω.), instead of prefiguring the happy side of the judgment to come, with the establishment of many mansions and worship in the temple, the temple is burnt to the ground, as are also the king’s house and everybody else’s houses. The very walls of the city are demolished.

As I said, everything is a desecration of form, and so also with the final three elements of the octave. The purification is an anti-purification, the illumination an anti-illumination, the perfection an anti-perfection. Firstly (ς.), the people rather than being freed from sin, are carried off by it, save only those who can’t afford to care for themselves, who are left to serve as slave labor in their own land. Secondly (ζ.), all that shone with light in the temple of worship (symbolic of illumination in a rather literal fashion) is stripped from its place and taken away. Lastly (η.), the chief priests and officers who were to embody in foretype the person of Christ, instead of prefiguring eternal life, are put to death in outer darkness. The bleakness is complete.

I do not expect the American sabbath, the advent of which I suspect is presently upon us, to be a virtuous rendition of the form. The day of preparation preceding it certainly was not. In the Sixth Party System, rather than the soul being purified of the irrational passions, the passions rather were purified of rationality. So what should we expect from the Seventh Party System, if indeed this octave is allowed to play out? There are a variety of ways for a sabbath rest to be expressed. I expect it somehow to take the form of death: a disintegration, a dissolution, or a betrayal of purpose.

Just look at the state of our current two parties. They are no longer capable of converting political knowledge into political actions. That’s kind of the job description of what parties are supposed to do. They can convert political feelings into political actions, but those feelings operate independently from reason and have become the masters of reason. No one can control those feelings except the false principality known biblically as “sin”, as when the Apostle talks of sin as a body with agency (e.g., Rom. 7). Our whole democracy is demonstrably sold to sin. Its behavior indicates nothing less.

But let me explain what I mean when I say our parties are no longer capable of converting political knowledge into political actions. The Democrats know full well that they need a better candidate for president next year than Joe Biden. He was already the oldest president ever at the start of his current term (topping Reagan), and his behavior is continually cringe inducing, to say nothing of his policies. He is suffering badly in the polls, losing to a candidate as bad as the historically unpopular president he unseated three years ago. If the Democrats could just nominate someone else instead, they would be in a much rosier position. They are aware of this. This is all knowledge that they have. But they are powerless to do anything about it. Donald Trump, meanwhile, has a grip over the Republican party that I liken to President Josip Broz Tito over Yugoslavia. As long as the party centers itself around him, they guarantee that they will have no future once he’s gone. Tito held the disparate Yugoslav factions together for as long as he was alive. After he died, a decade of disintegration foregrounded the horrific chaos of the Balkan Wars. If the Republicans can’t hold themselves together with anything but the person of Trump — and Trump in a potential second term would be as old as Biden is in his present term — they are dooming themselves. They can see this. This is knowledge that they have. No one can do anything about it. The irrational passions are in full control.

So that you’ll know I’m not the only one thinking these things, Matthew Yglesias recently wrote, in an article citing an upcoming book I’d be interested in reading called Hollow Parties: The Many Pasts and Disordered Present of American Party Politics,

As the system has become increasingly democratic, ... the nominees have gotten increasingly unpopular.... [I]t follows pretty straightforwardly from the fact that we’re not letting political professionals do their jobs. We have lots of columnists doing takes like “Hey! Trump is a criminal and Biden is old! Voters don’t like that!” as if leading Democrats and Republicans are unaware of this information. The issue is that they can’t do anything about it. The voters are like a child whose parents don’t enforce a bedtime — he is superficially getting what he wants, but in practice, he’s cranky and upset all the time.

The fruits of populism! The fruits of democracy! Plato warned us. Tyranny is upon us — us, a nation of rebels whose entire muscle memory knows only one setting, which is to resist tyranny. The “political professionals”, the experts who led us where we are, aren’t going to save us. Reason is beyond reacquiring by the humanist means to which we’re committed. Our Zeus is overthrown.

So what happens next? It should be plain to see that the type of pattern-seeking I’m engaging in does not have the predictive power that one would require who strove to control either history or one’s material fortunes within it. That’s not what any of this is about. The pattern of sabbath rest that I envision us falling into at present can take many varied forms. The idea of the party system in U.S. politics is somehow undergoing death, but how? Maybe the two parties will dissolve into a multitude of parties, and we’ll suffer from the tyranny of chaos. Maybe one party will permanently dominate all opponents, and we’ll suffer from the tyranny of control.

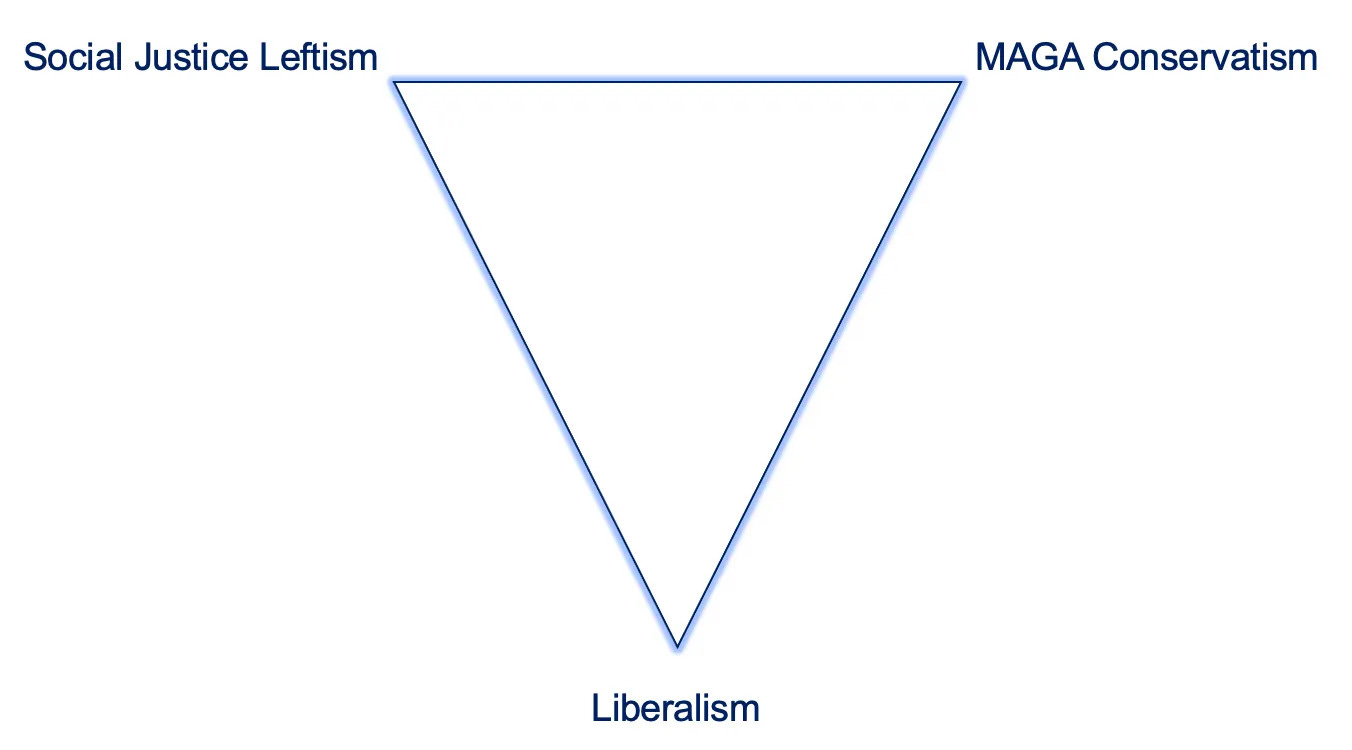

Or maybe the magnetic polarization of the two parties will break apart such that three parties form, something along the lines of what Nate Silver described recently. He keys in on the wedge forming on the left between old school Enlightenment liberals and what he calls the Social Justice leftists, highlighted by the current violence between Palestinians in Gaza and the Israelis. I likewise would point to the recent House Speaker chaos on the right as signs that the GOP is no longer functioning as a party and is at risk of falling apart. That break I could see occurring first since it’s the nature of thymos to divide. And I can see the Democrats triumphing for a moment as it happens, just before the polar force connecting the two parties drags them into a similar break among their own ranks. What could plausibly result is the three-party system Silver describes, with centrist Republicans and Democrats joining forces — though probably not under the name of liberalism. (Maybe they could call themselves the Enlightenment party, or just go full irony and call themselves the Illuminati.)

This triangular situation — in which, as I see it, a party would be attempting to represent the power of logos over thymos and epithymia — could cripple electoral politics in the U.S., since if no presidential candidate wins a majority of the electoral college (which would happen easily in a three-sided race), the House of Representatives is tasked with picking the next president, like it did in 1824. In our current populist environment, it’s hard to imagine there being much tolerance for that happening.

Then again, maybe there won’t be three parties. Maybe there will continue to be two parties but internally they will be as chaotic as a multitude, while together they’ll function as a monolithic tyrant. Maybe the two parties will persist, but their identities will be in constant flux. Maybe it’ll be like the 1850s when everything falls apart, except it’ll take a generation or two for a realignment to put things in order again — maybe it’s the whole idea of realignments that takes a sabbath rest.

One thing that I think should be mentioned is that I wouldn’t automatically expect everyone in the Seventh Party System to experience it as a period of want and suffering, either material or spiritual. I’m forecasting a kind of political death, but the fear of death is not generally how I would counsel anyone to anticipate what’s ahead. In all historical circumstances there have been those who prosper (physically, psychologically) and those who don’t. That’s not likely to change any time soon, and I’m sure when the Seventh Party System passes there will be plenty who regret seeing it go. Putting aside material concerns, psychologically, this era may be a time of anti-illumination as far as U.S. politics are concerned, but that wake-up call might be exactly what a lot of certain people need in order to undergo actual purification, illumination, and perfection. The fear of pain can be transformed into the fear of God, which is the cessation of sin, and therein lies the path to gratitude and love. Sabbath rest and death alike symbolically denote renewal. I can already foresee the nostalgia to come once the up and coming generation’s opportunity for repentance passes. I think a certain kind of pre-nostalgia for that opening in time would be the wise way to anticipate it. You might even call it hope. The sabbath, after all, is when the Messiah rips open the belly of hades and frees all the dead languishing in corruption. The world through vanity may turn this pattern into something negative, into something antichristian, but that doesn’t prevent anyone in their own life from flipping it back to its intended purpose.

Η. The Eighth Party System (dates unknown)

A new god rises

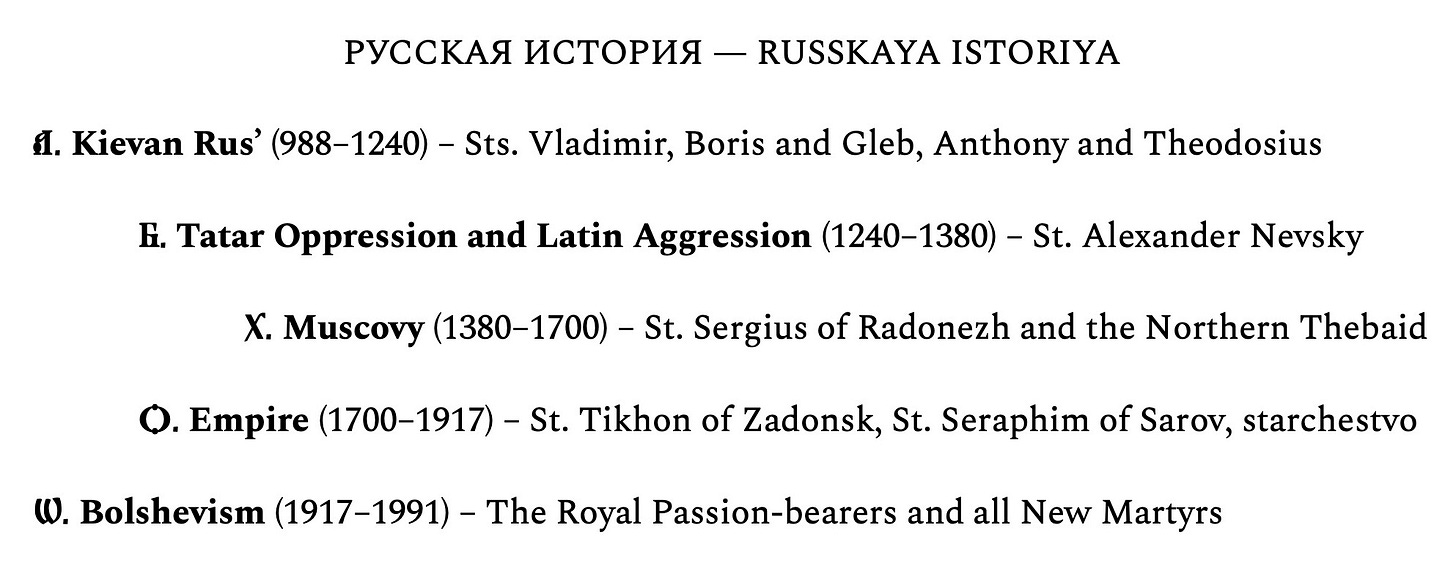

I’ve long thought Russky salvation history (Russky being the adjectival autonym not only for, say, Muscovites, but also historically for Kievans) conforms to the cosmic chiasmus pattern through the Soviet era. Like so (listing with each period the saints that exemplify what was best about it):

The Kievan holy fathers were like Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; St. Alexander Nevsky like a new Moses; St. Sergius a new David; the holy startsy like new Elijahs and Isaiahs and Jeremiahs and Ezekiels and Daniels; and the New Martyrs like new Maccabees.

I never knew, though, what to make of the post-Soviet era. Was it the beginning of a new cycle? Was it an ongoing octave? Or was Russky history in fact dead, and are the zombie states that have taken its place just waiting for the rest of the world to catch up with its apocalypse? That last one had long been my best guess. Now, however, ever since this autumn when I had the whole of U.S. history appear before my eyes, I suspect Russky history is an ongoing octave, and that for the past thirty years it has like the U.S. been in a stigma-period, with a Saturday and a Sunday in its future. Between 988 and 1789, the land of the Rus’ and the “land of the free” may have had disparate start times, but maybe, on account of an accelerated time schedule in the U.S., the two great powers flanking the Northern Hemisphere and determining so much of world history have synced up with each other in their life phases. The discovery of the New World has always had a mystical connection with the Orthodox East on account of 1492 AD being the year 7000 from the creation of the world according to the Byzantine calendar. Because Constantinople had fallen forty years earlier, because the creation of the world was completed and blessed in seven days, and because “one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day” (2 Pet. 3:8; cf. Ps. 89:4), when the year 7000 arrived Russians commonly believed the old world would pass and a new world would dawn. In a way, with Columbus’s discovery of the Caribbean islands that year, they were right. But as their prophecy was worldly minded, so was the fulfillment. The discovery of the so-called New World wasn’t the real eighth day, but the type of it, one easily idolized and given a negative mode as an anti–eighth day.

An antichrist is so called not because he’s hostile to Christ (though out of envy he inherently is), but because he apes Christ, competing for the Lord’s position in the eyes of the saints. The Greek anti has a sense of “against”, it’s true, but more fundamentally it means “instead of”. An antichrist is anyone or anything that is worshiped instead of Christ, fulfilling the patterns of Christ as plausibly as possible so as to deceive. Teaching about the end times, Christ warns, “Take heed that no man deceive you, for many shall come in my name, saying, ‘I am the Christ,’ and shall deceive many,” and further, “There shall arise false Christs, and false prophets, and shall show great signs and wonders insomuch that, if it were possible, they shall deceive the very elect” (Matt. 24:4–5, 24–25).

Judas made of himself such a false Christ, trusting in his own human reason more than the divinity of Jesus. When Judas comes for Jesus in the garden, Jesus gives us a model of how to behave towards an antichrist when approached by one: He neither runs away nor goes on the offensive. The option of fight or flight, after all, corresponds to the pattern of thymos and epithymia. Accordingly, when a companion of Jesus cuts a servant of the high priest’s ear off, he is rebuked and told to put his sword away lest he perish by it (Matt. 26:51–54). When a young disciple in a linen cloth is grabbed, he runs away naked, greatly to his shame (Mark 14:51–52). Christ, both God and man, shows another way, a divine way, fearing not what men shall do to Him. Christ neither backs off nor pushes His betrayer away; He accepts both Judas’s embrace and his kiss, and He calls him friend when he does it. No antichrist is worthy of Christian fear, nor should indignation ever obscure one’s vision of the image of God in all men.

Out of the chaos of the Seventh Party System, we can expect a savior to come and restore order — a type of resurrection. This is how the pattern goes. Theoretically, this political development could even be a thoroughly positive one, a real resurrection from the death of godlessness. But in the case that this realignment is, I don’t know, at all in keeping with the trajectory of U.S. history, deception should be prepared for. Now, this savior of the Eighth Party System needn’t be a global antichrist; an American one would fulfill the pattern just as well. (Though maybe we and the Russkies could share one; that would be a sweet denouement.) The order that is restored, moreover, is not evil in itself and should not be treated as so. The vanity with which the order is restored is what separates one from God, and it is to be scorned even at the cost of one’s life. It is very important not to oppose the antichrist in such a way that repels you from Christ at the same time. Those who would set themselves over men for evil purpose often operate in this way, so as to seduce to the left those susceptible to desire and at the same time provoke to the right those susceptible to anger. True love for both God and man preserves the saints from either trap. It may cause them to be hated and persecuted by the men and women of this world who would much prefer them to be either seduced by desire or provoked to anger — or at the very least afraid for their lives. But in them who put their wills to death for the sake of Christ, who say with God the Son to God the Father, “Not my will, but Thine be done,” there is resurrection, and there is life, enough to fulfill the pattern of the eighth day in all virtue. In Christ, “He who endures to the end shall be saved” (Matt. 24:13), and if there is salvation to be had in the end, then the end isn’t much of an end, is it?

Other than all that, I can’t say much else about this party system. As I said before, this method of pattern-seeking isn’t about predictive power, not in any way that would satisfy those looking to control knowledge. It has all been a matter of pious conjecture, a gaping for knowledge beyond my station, over which I can claim no mastery. Whereas “Love never faileth,” as the Apostle instructs us, “whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away. For we know in part, and we prophesy in part. But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away” (1 Cor. 13:8–10).

My dear readers, before I send you off with one of my favorite moments from recent American politics, I’d like to thank you for taking this journey with me.

When I saw the possibility of writing about U.S. political history, I thought it would be a good chance to get it all out before the year was done — for one thing, so that I could turn the page in 2024 and, amidst all the election noise, write on more joyful topics in shorter, hopefully more frequent postings — but also so that these writings could be on file for the crazy year of politics ahead, in case people found them helpful amidst all the Sturm und Drang. I hope they find their audience.

And if any readers have been dissatisfied with the political commentary or the sheer length of the pieces I’ve put out the last couple months, do know that I aim to transition to more digestible, more edifying content going forward. I myself look for this relief. We’ll see what I can manage! I’ll start with a piece on the Christmas octave as soon as I can.

For now, that’s it. I’m done. I’m finally finished talking about politics.

Thank you for this incredible series! I really enjoyed reading, albeit slowly and perhaps with limited comprehension.

There is so much to take in here and digest, thank you for a very insightful story of American politics.

I wonder if you could comment more on American Christianity and it’s role in the story, specifically in the sixth party?