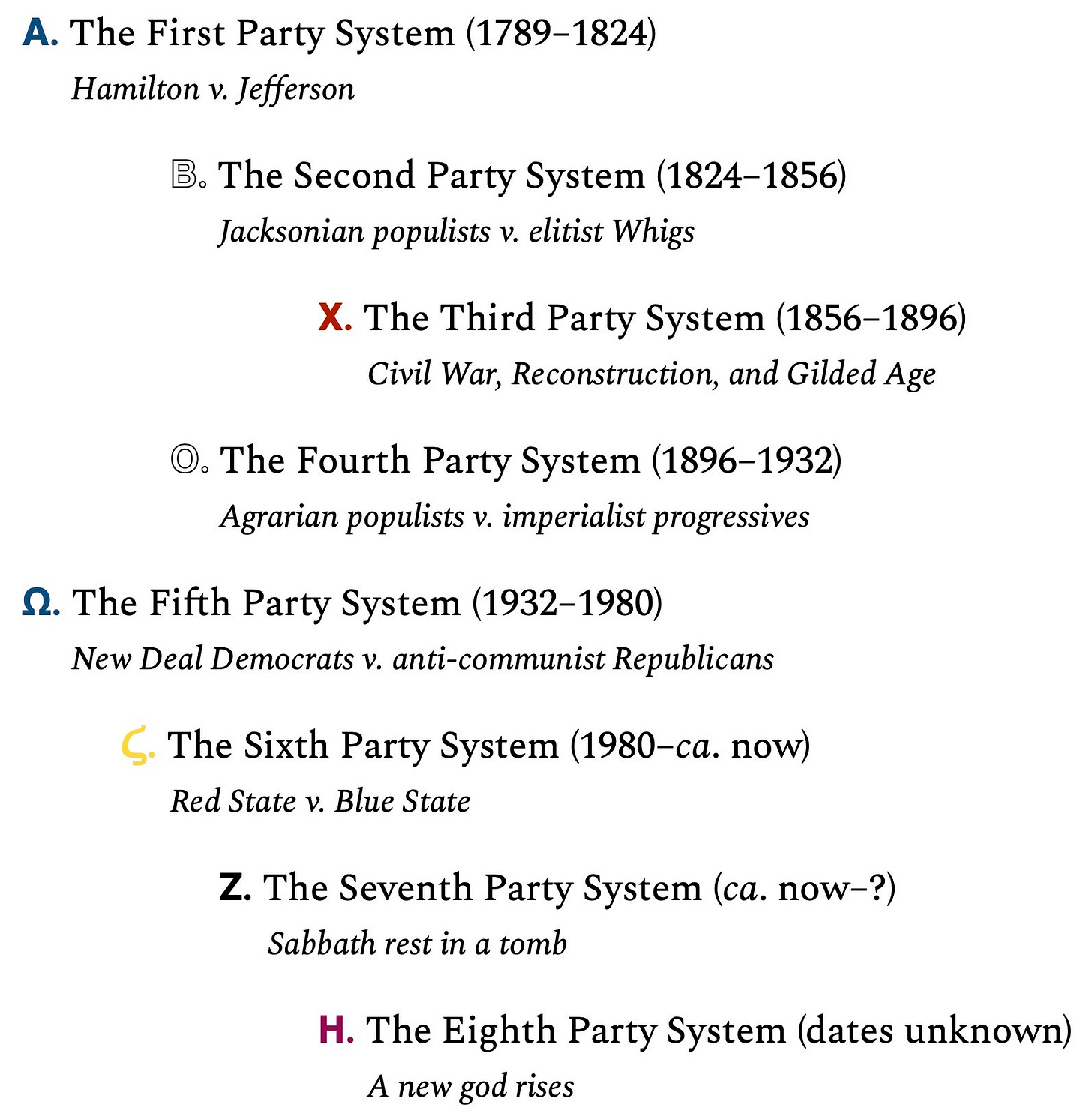

The sequence of party systems in U.S. political history, part 2

Continuing the octave

See Part 1 here. To get back into the narrative, let’s remind ourselves of the overall outline:

The octave can be thought of in two parts, the fivefold chiasmus and then the triadic ascent, like a five-day work week crowned with Friday night, sabbath rest, and the Lord’s Day. Here we pick back up with the Fourth and Fifth Party Systems, completing the chiastic work week.

Ο. The Fourth Party System (1896–1932)

Agrarian populists v. imperialist progressives

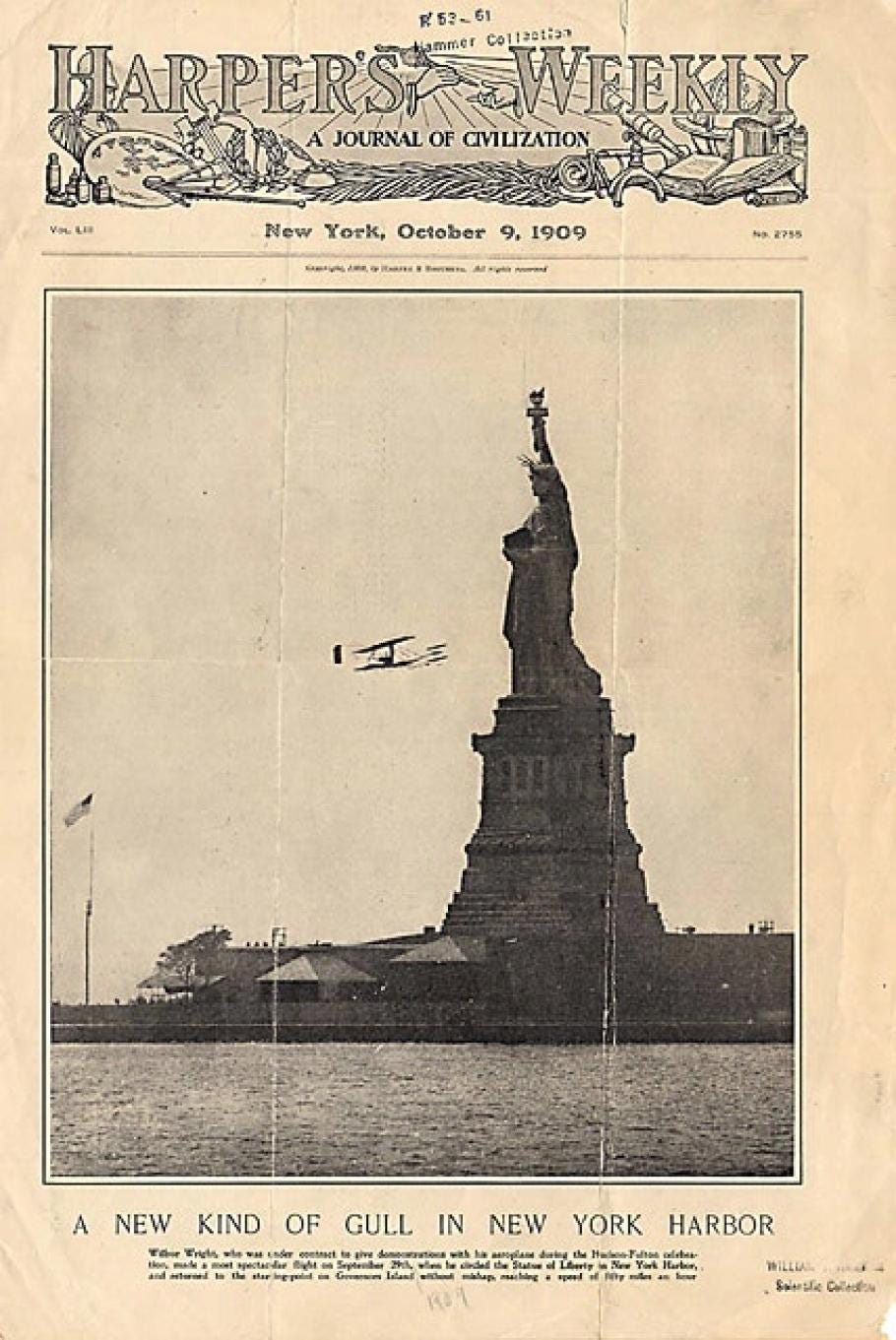

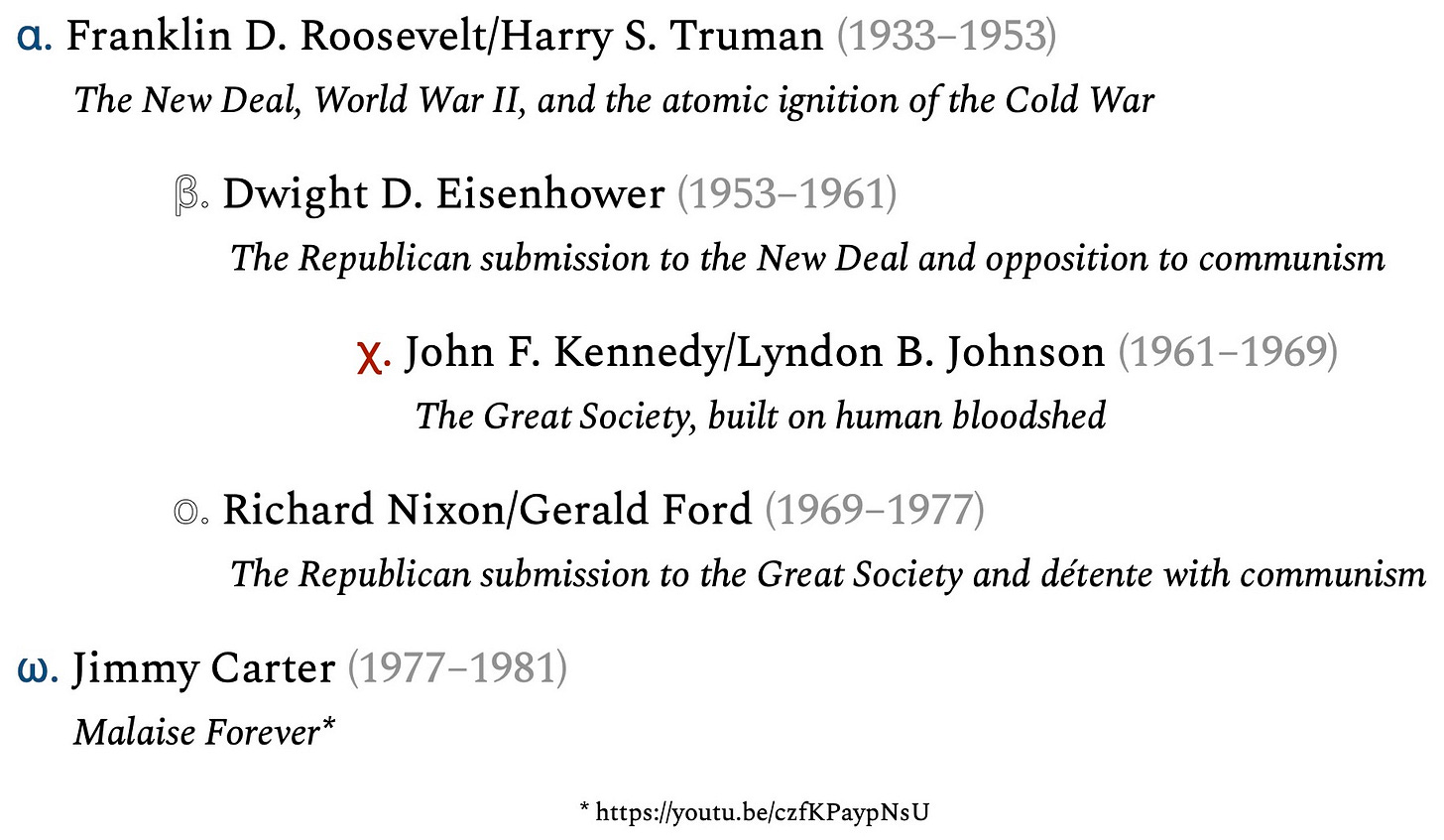

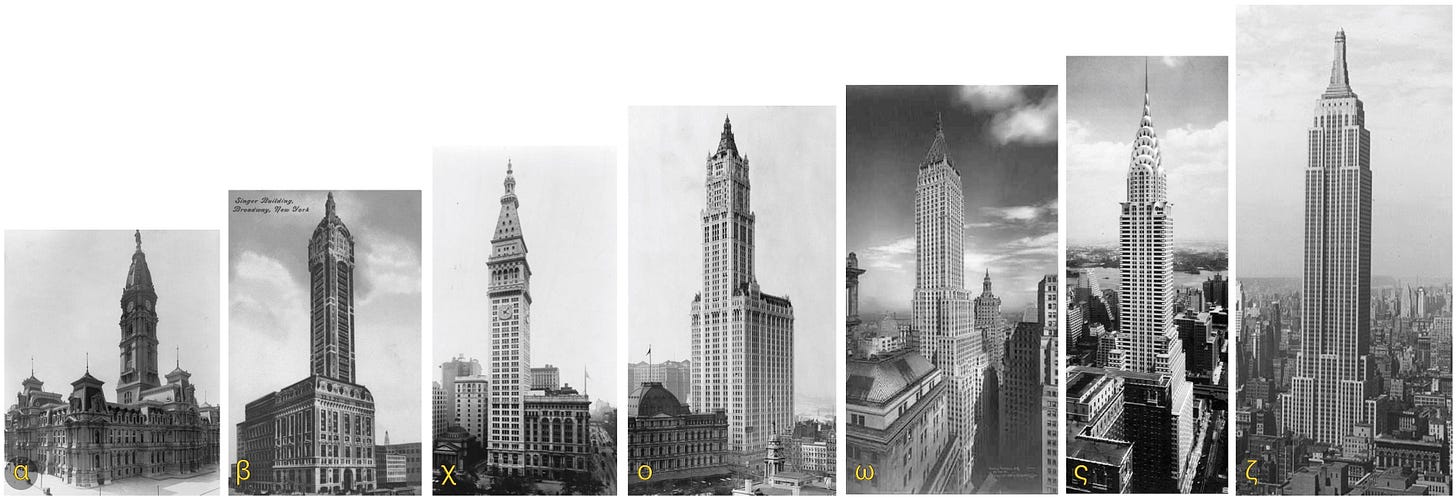

Readers of “The Cosmic Chiasmus” following the pattern of the first five party systems would expect to find here in the Fourth Party System a type of “reunification of that which had been differentiated.” In the beginning, the First Party System established the genesis of the country, but it was all very aristocratic — a country for the few. In the Second Party System, power descended down the social mountain from the few to the unwashed many, or analogously, from reason to the passions. Thus, after the paschal journey through the central inferno of the Third Party System, we would expect to find here, in the Fourth Party System, typology of a fruitful union resolving the dialectic of the Second, something similar to a marriage and the bearing of children. That’s exactly what we get in the so-called Progressive Era succeeding the Gilded Age. The harmonies of hierarchies, however — between industry and agriculture, business and labor, urban and rural, elites and common folk, rationalist reforms and populist emotions, heaven and earth, men’s suffrage and (gasp!) women’s suffrage — were forged more in the spirit of technology than virtue. Heaven and earth were bridged by steel skyscrapers and their elevators, for example, and, most spectacularly, by the power of aviation. Men and women found unity of power less in sacrifice and obedience than in mere constitutional amendment. The children they bore came in the form of annexed territories, sentenced to imperialist control.

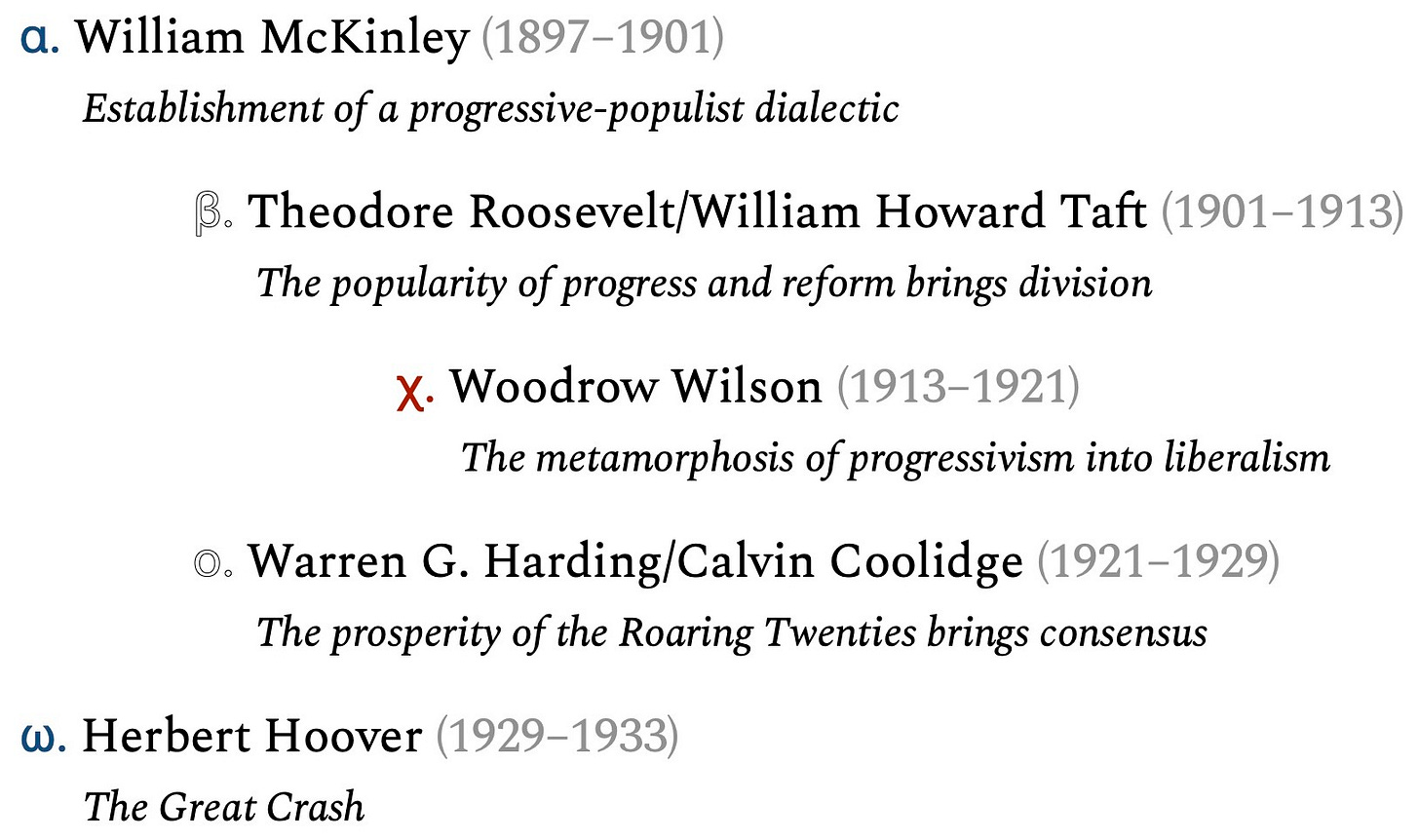

William Jennings Bryan appeared out of nowhere in 1896, giving what very well could have been an inconspicuous speech at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. But it was anything but inconspicuous. A 36-year-old former House Representative from Nebraska, with no national profile to speak of, he was part of a growing populist movement against the business and political elites who were oppressing common folk, especially farmers. All the Gilded Age corruption, which his own Democratic party had played its part in, was coming to a head with the ongoing 1893 depression, easily the worst of its kind that the nation had ever seen. Bourbon Democrats like President Grover Cleveland believed in stemming corruption by limiting government intervention as much as possible. But that also meant refusing to help those in need or protect people from financial tyranny. Cleveland, just like the Republicans, believed in maintaining the status quo of the gold standard, which helped facilitate big business but provided no opportunity for the agrarian populace to get out from under the boot of deflation.

Bryan instead advocated taking active measures to protect the people from the excesses of industrial capitalism, to enforce inflationary policies that would have counteracted the prevailing deflation — above all by adopting the bimetallic monetary standard that had been the country’s policy originally, but hadn’t been in effect for decades. The gold standard, rather, was where the country settled after the Civil War, by means of the popularly despised Coinage Act of 1873. Bimetallism means using silver as well as gold as a basis for money, and so insurgent populists crafted a movement out of the “Free Silver” cause. A whole third party formed around just this, the Populist party, but Bryan appropriated their cause as his own. A talented orator from an early age, he gave the speech of his life in Chicago, voicing the grievance of a nation that felt itself being crucified on a “cross of gold,” as he put it in his flashy finale, stretching out his arms like a crucifix. In just this moment, the entire Democratic party realigned around him.

He thus suddenly became a viable candidate for the party’s presidential nominee, and he even won the nomination, becoming the youngest ever to do so for a major party. He lost in the general election to Republican candidate William McKinley, and did so again in the rematch four years later. But by founding a newspaper, serving as its editor, and touring as a speaker, he found great riches and fame and made sure his vision of agrarian populism was the pole around which the Democrats rallied. It was a pole of epithymia, however, to which his politics of economic desire and his prosperity in the media attest.

As an Evangelical Christian in the midst of the Third Great Awakening, Bryan’s politics were the product of his faith, according to which he valued the country’s heartland over its cities, and matters of the heart over the head. But the Protestant American culture current in his day was incapable of discerning the difference between the heart and the activity of the passions. We can see this symbolically in L. Frank Baum’s hit children’s book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, first published in 1900. The three friends Dorothy makes along the Yellow Brick Road neatly correspond to the traditional tripartite rendering of the soul: The Scarecrow lacks a brain, the rational aspect (logos). The Tin Woodman lacks a heart, the desiring aspect (epithymia). And the Cowardly Lion lacks courage, the incensive aspect (thymos).

This specific model for mapping the soul on the body results from a particularly materialistic, avaricious culture (the Greek word for avarice literally means “love of silver”). Biblical symbolism is more apt to associate logos with the heart, and the two lower passions with the kidneys (the “reins” in the KJV). But the modern American apostate thinks of the logos in terms of the brain, and that leaves the heart to be confused with “feelings” and indistinguishable from the lower passion of epithymia. When an Evangelical agrarian populist like Bryan expresses polarized political resistance in terms of siding with the heart over the head, he contributes to a Protestant flavor of the Counter-Enlightenment that remains every bit subject to the same dialectic of corruption that created the political powers he would have us resist. There’s potential for relative good there, don’t get me wrong, but also relative evil; the mixture of the two is what corruption means. And the way polarization works, there’s no inherent advantage in relative good to be found on one pole over the other.

We should speak of the other pole. The Democrat Bryan may single-handedly have sparked the realignment and set the terms for the whole Fourth Party System, but it was his Republican foes, responding to his populism by realigning around imperialism and progressivism, who found a winning combination and gave the Progressive Era its name.

Arguably their imperialism preceded their progressivism. President McKinley’s domestic policies were standard for the Gilded Age — indeed, as a member of congress, he had been a primary architect of the Republicans’ protective tariff policy designed to give American manufacturers an advantage in domestic markets. He also supported the gold standard, making it official U.S. policy at the end of his first term once it was politically safe to do so. What made it safe was the Klondike Gold Rush in the U.S. territory of Alaska injecting new wealth into the depressed economy — as well as the success of the nation’s imperialist adventures in the Spanish–American War. Entering this war was made a reality first of all by the immense sympathy on the part of Americans for Cuban rebels in their war of independence from Spain. This years-long conflict was turning more and more merciless, and McKinley’s attempts at diplomacy availed nothing. In February 1898 a U.S. warship offering aid to the Cubans exploded and sank in the Caribbean — very possibly from a fire in its own coal bunker, but a court of inquiry decided it was from a Spanish mine. Congress declared war, and within two weeks the navy was fighting and winning battles in the Philippines, the war not being confined to the Caribbean. It proved a swift victory for the U.S., and in the concluding treaty ten months from the start of the war, McKinley negotiated the purchase from Spain of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. Hawaii had also been annexed in the midst of the war, its naval base proving crucial to American interests in the Pacific.

Epithymetic Democrats like Bryan were opposed to these imperialist adventures, but the thymic exhilaration of international expansion proved more popular. (The resistance was ironic, as half a century earlier it was epithymetic Jacksonian Democrats pushing for Manifest Destiny in the Mexican War, of which thymic Whigs were critical.) The 1900 presidential election would be a repeat of the previous one, but McKinley had first to find a new running mate since his vice president had died. He allowed the Republican Convention to pick who it would be, and a popular imperialist adventurer who had legendarily fought alongside Cuban rebels carried the day — Theodore Roosevelt, at that time the Governor of New York. It wasn’t certain he would be chosen since his progressive agenda for reform was an affront to the party bosses, but some of the same party bosses in New York also wanted him out of the Executive Mansion in Albany. As it happened, just six months into his second term President McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Theodore Roosevelt acceded to the presidency (the youngest ever to do so, incidentally), and the Progressive Era was in full swing.

A word now needs to be said about the descriptor “progressive,” because it originally meant something in American politics vastly different from how it is used now. American progressivism was championed originally by Republicans, who were also right-wing, predominantly urban, and decidedly capitalist, even if anti-trust. Progress meant moral reform of the soul’s passions and of society’s, and it was to be guided by reason, as well as by those aspects of religion deemed rational — the “social gospel” was especially prevalent in the ongoing Third Great Awakening. The desires and aggression of the base aspects of man were the targets of reform, temperance and civility the goals. This sounds near ideal from my perspective, and typologically it was. In actuality, among the upper classes, well, the trendiest fashion was concern for the welfare of others. This wasn’t always for the better as motivations weren’t pure, and charitable societies could be usurped for the purpose of preferential social advancement. In his 1916 masterpiece Intolerance, D.W. Griffith (very much an agrarian Democrat) mocked the progressives of this party system as a bunch of nosy, puritanical rich ladies who hoarded resources from the working class and distributed them unjustly, arranging for babies to be taken away from their rightful mothers merely because they suffered from lack of resources (the resources the charities were hoarding). No doubt the progressive deployment of rational reform was corrupt and worthy of polar opposition, inasmuch as its motivation was thymic control of society. But relative to the corruption of the Gilded Age, massive strides were made toward the public good under the banner of progressivism.

I should admit that — aside from all the imperialism — I have a tremendous amount of affection for this era. As the cities lurched upwards into the sky, and Ford motor cars began traversing town and country, baseball was king, and nickelodeons transformed the theatrical experience (starting in my hometown of Pittsburgh in 1905). In stage performances to that point, the positioning and movement of actors was designed so as to accommodate a plurality of perspectives from throughout a theater. Stage blocking works differently for cinema because there’s only one perspective to account for, the camera’s. You take the theatrical spaces where vaudeville and burlesque shows had been mounted and instead project movies there, and suddenly the audience, though variously seated, now is unified in a single perspective, as if they’re all at once crouching before the same keyhole. Accordingly, there is a galvanizing effect on national identity that occurs through the process of modernization, including both mass media and the industrialization of manufacturing and farming. High and low, east and west, north and south — everything is united in one hierarchy of identity. Major League Baseball consolidated its factions, and the first World Series was played in 1903 between Pittsburgh’s National League team and Boston’s American League team. Baseball is a pastoral sport, but one that originally thrived in cities. It occurred in oases of green tucked in jungles of steel and concrete, a clockless game that determined its own pace amidst human lives otherwise tightly regimented by timed schedules. Like infield and outfield, it combined urban and rural in one team sport, nationally beloved.

Movies and baseball are my favorite worldly things, and within this larger narrative I’m exploring now, the reason can be seen why. It’s the ever-pleasing and fruitful hierarchical balance of unity and plurality achieved in the omicron-stage of my nation’s life. This is when photographer Lewis Hine helped change labor laws through the iconographic power of his images — images of individual Americans in which all Americans could see themselves as in mirrors. The social reality pictured wasn’t always pretty, even when the photographs were aesthetically gorgeous, but then the contrast of the two qualities would inspire change in favor of the beautiful.

I wrote about Hine in my essay on Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978), a film taking place in the Texas Panhandle during the 1910s. The joke in the finale to that movie is that the fugitive Bill, try as he may to disappear in the wilderness of the American landscape, cannot escape random people all around him. The Wild West by this point in time is teeming with women and children, with society and law, and they swallow him who through negligence has fallen into desire and violence. In the Progressive Era, he who would disrupt the harmony of the world with dissipative passions is buried and passed over. It’s a myth my heart responds to, even if I know the image of harmony was achieved only in type, and the burying of souls was more tragic than cathartic.

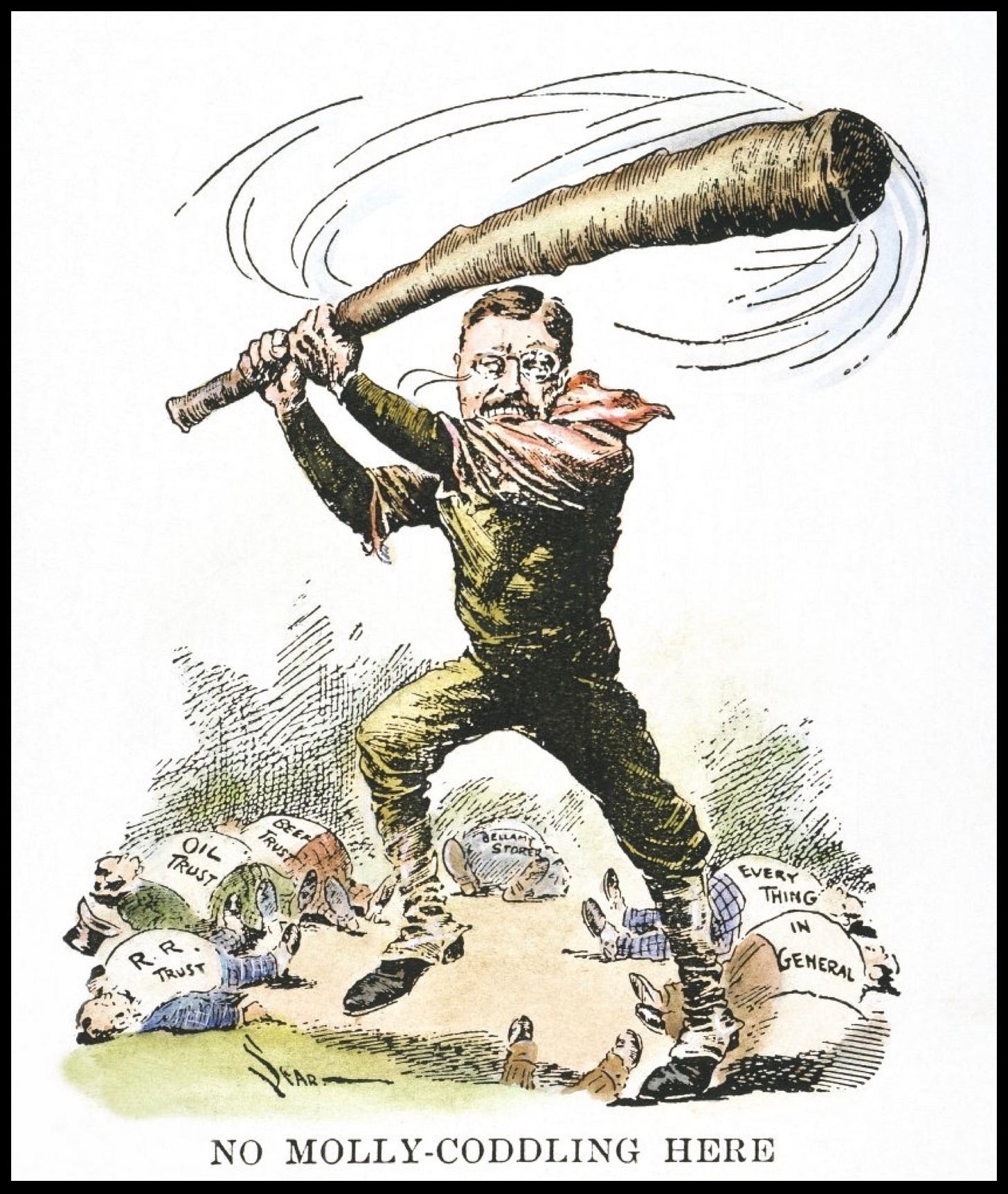

Speaking of child labor, President Teddy Roosevelt actually stopped laws restricting it from passing on a national level; the movement for them, however, thrived on a state level, and Roosevelt’s other progressive achievements are many. Like no president had done before, he aggressively broke up trusts, protecting consumers from artificially raised prices. He investigated and prosecuted corruption in the government. He made gains in natural and historic conservationism like no one else has, creating the National Parks and the United States Forest Service. He passed badly needed food safety laws, solving problems the likes of which were exposed by muckraking journalists like Upton Sinclair, a socialist. Imagine a world in which pro-business Republican politicians at times listened to and responded agreeably to the outcries of socialists. Polarization persisted between populists and elite reformers, but it was also a fruitful dialogue in which those in power could be genuinely responsive to people’s needs. Populist Democrats were definitely the weaker party by political standards, but they deserve credit for steering the issues and keeping the dominant Republicans accountable to their needs in the midst of massive cultural transformation.

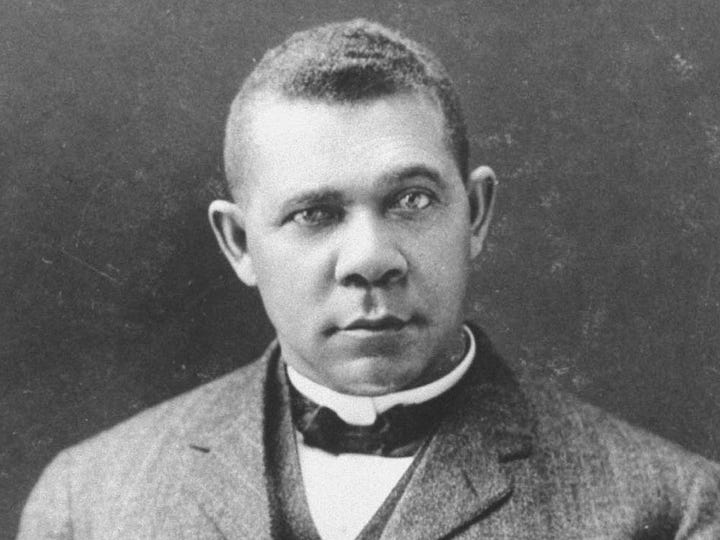

As such, Roosevelt was an active regulator who sought influence in most aspects of public life, in all things aiming for fairness and equality of opportunity, according to what he called a “Square Deal” for all Americans. His civil rights record was spotty, but the era over which he presided saw tremendous cultural progress for African Americans by means of their own achievements — another reason to be particularly endeared by this period. This was the ragtime era, when black people came to participate in American culture even to the point of creating their own political dialectic, as with the rivalry between Booker T. Washington and his Tuskegee Institute, on one hand, and W.E.B. Du Bois of the Niagara Movement and the NAACP (est. 1909), on the other. Though conflicting like thymos and epithymia (respectively), both sides held in store essential, highly reasonable messages for their people — the dynamic could not be more American. And insofar as it was fruitful, it imaged the best American progressivism has to offer. Yes, segregation continued to be a monstrous burden, but within it, black culture, black newspapers, black businesses and institutions, flourished.

Success went to Teddy’s head, no doubt. By the end of his second term in office, he had lost some effectiveness as a leader, having pushed his own party too hard towards reforms and imposing the power of the executive branch in too many places. His handpicked successor William Howard Taft and he had a falling out once Teddy was out of power. A dedicated regime of reform like Roosevelt’s places great power in the top, and that was the major theme of the era and what allowed the U.S. to become such a great imperialistic power in terms of both global commerce and military might. But it also brought division among the Republicans and an opening for Democrats in 1912.

Unhappy with President Taft for not being radical enough, and also for championing diplomacy instead of imperial “big stick” belligerence, Roosevelt tried running against him for the Republican nomination that year. And for the first time there were primary elections in some states, about a third. This development was part of the reform movement, appealing to both progressive and populist impulses, getting the party bosses to cede some power to the people in choosing the candidates. The primary will become a major vehicle for political change later, but for 1912 it did not make much difference. Roosevelt still had some pull with the people, but he only won half the primaries; and most states were still controlled by party elites that had had enough of his outsized personality and imperial will. Rejected by his party and bullheaded as ever, he started his own short-lived Progressive party, which split the vote and threw the election to the Democrats, who had opportunistically nominated a progressive candidate of their own, Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson — the second of only two Democrats to win the presidency between the Civil War and the Great Depression (after Grover Cleveland) — had previously been a Bourbon Democrat, the kind that was at odds with William Jennings Bryan, but as governor of New Jersey he had changed with the times to adopt a progressive agenda that appealed to populists. The difference between him and Republicans is that he favored state over federal power to enact reforms, and also he was against the protective tariffs favored by Republicans, preferring to replace them with a federal income tax instead. Tariffs on foreign goods helped American businesses, but placed a burden on the consumer class, including all the poor. A federal income tax, on the other hand — the constitutionality of which was established under Taft by a coalition of populist Democrats with some progressive Republicans, who together pushed across the Sixteenth Amendment — was seen as a method for shifting that burden onto those who had more wealth. That made Wilson different from the Republicans. The influential Bryan endorsed Wilson (and joined his cabinet as Secretary of State, the highest office this epoch-defining politician ever held), and he won. Wilson’s presidency would be transformative for politics in the twentieth century, but for now it’s time we look at this outline:

A three-week banking crisis in 1907, towards the end of Roosevelt’s presidency, had highlighted the weakness in the American system, which since Andrew Jackson had lacked a federal bank. Throughout Taft’s presidency, work was done towards fixing this problem, but debate in congress delayed action. As it happened, one of Wilson’s priorities when coming into office, after lowering tariffs and instituting a federal income tax, was creating the Federal Reserve. In designing it, he and congress sought a compromise whereby the Fed would consist of twelve private regional banks overseen by a central Federal Reserve Board controlled by the government (with board members appointed by the president and confirmed by the senate). The United States would have a centralized banking system again, which was seen as advantageous in times of financial distress. The Democrats were the heirs of Jeffersonian democracy and Jacksonian populism — the strains of anti-federalism that carried over into federalist America. Yet here we have a Democrat, Woodrow Wilson, following that tradition and ending up instituting a federal income tax and creating the Federal Reserve. To fund entry into World War I in Wilson’s second term, the Fed had to be augmented in its powers over the value of money, and so it was. It now had powers to induce or restrict inflation.

Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, central to the First Party System, was transformative for his party in how he incorporated his opposition’s policies, and something similar happened with Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. He had previously preferred that progressive reforms occur at the state level, but in the run-up to the 1916 election, he was convinced to support a slew of federal labor laws, some of which he thought were unconstitutional, in order to sway progressive voters, especially the growing base of women voters, who tended to support greater federal power. Wilson, furthermore, objected to Republican imperialism, and yet as president persisted in the occupation of Nicaragua, continued meddling in the ongoing Mexican Revolution, and authorized invasions of first Haiti and then the Dominican Republic, instigating years-long occupations of those countries. He was determined to stay out of World War I from when it began in 1914, and this pacifism was an important issue in his re-election campaign, at which time it was claimed voting for Republicans meant electing to go to war. German provocation proved too strong for Wilson, however, as not a month into his second term, he was the one requesting congress for a declaration of war. His vision for ending the conflict, moreover, included establishing an intergovernmental body dedicated to maintaining peace called the League of Nations, a plan which came to pass with him as the leading architect. Hence the trajectory of his anti-imperialist foreign policy landed him not only as occupier-in-chief of Latin America, but as virtually the founder of political globalism.

Wilson’s League of Nations couldn’t avert a second global conflagration anymore than his Federal Reserve could avert a catastrophic financial collapse. But his epithymetic Democratic synthesis of progressivism and populism, later to be recognized as liberalism, would sprout into something longer lasting in a subsequent party system.

For now, the pendulum swung back to the Republicans in the 1920 presidential election. World War I had established the United States as the supreme global superpower. With the European film industry decimated, for instance, Hollywood developed a stranglehold on culture around the world. That galvanizing effect on audience perspective manufactured by cinema that I described earlier? It was now causing peoples across the globe all to be peering as through the same keyhole at Mary Pickford, or Douglas Fairbanks, or Charlie Chaplin — propaganda for American values seizing everyone’s minds by the seductive power of cinematic pleasure. Voters in the U.S. now looked to their leaders to be stewards of this global dominance, and pro-business Republicans — a little more elitist than populist, respectful of progressive gains that had been made, but no longer eager for new ones — fit the bill.

First there was Warren G. Harding, who soundly beat Democrat James M. Cox despite there being little distinguishing qualities between them; they were even both from Ohio and had both been newspaper editors before entering politics. World War I and the Spanish flu had upset society such that no grand political idea other than Harding’s motto of “Return to Normalcy” was at stake. The Republican choice for vice president was also telling. Calvin Coolidge had first came to national attention by quickly shutting down a police strike in Boston when he was governor of Massachusetts. He brought in the National Guard, fired all the striking cops, and began recruitment of an all new force. He resoundingly rejected the notion that the strike had had any justification. This occurred in 1919, when Americans were freshly scared of leftist revolutions, and the labor movement was put on warning by the public. Coolidge’s actions were popular. Women’s suffrage and the Prohibition of alcohol may have been made constitutional in 1920, the last year of Wilson’s presidency, but by that point in history the Progressive Era was reaching its limits. Americans were becoming more conservative, albeit the progress they had made is what they wanted to conserve.

Under Harding, in response to a post-war deflationary depression, there were tax cuts for higher income brackets and the refusal of bonuses for war veterans. Progress for minority communities was arrested by white supremacists as the Ku Klux Klan was in its heyday, the Tulsa race riots destroyed Black Wall Street, and oil-rich Osage Indians in Oklahoma were murdered regularly without consequence. Harding died of a heart attack in 1923, two and a half years into his presidency, and his vice president Calvin Coolidge acceded to the office, also winning re-election in 1924, another landslide victory for the Republicans. These, alas, were the Roaring Twenties, when material prosperity flourished, and commercial radio began filling in the thoughts of lonesome souls across the nation, increasing cultural uniformity.

“Silent Cal” Coolidge, meanwhile, was a calming, steadying presence in the White House, preserving progressive gains but not wanting to increase the size of government past its current point. When farmers could have used financial relief, Coolidge vetoed progressive Republican plans to give them some, so as not to balloon bureaucracy. He resisted aiding victims of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 for the same reason. Technical modernization, not political intervention, was seen as the path to progress in the Roaring Twenties. Coolidge did, however, advocate for federal anti-lynching laws, though congress preferred the states handle that; nonetheless, as the decade wore on, the Klan membership bubble burst, and they lost their prominent national profile, decreasing the urgency of the issue. Under J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau of Investigation, moreover, the Osage murders were solved and prosecuted. All reservation Indians received full citizenship rights in an act of 1924.

The Secretary of the Treasury throughout these Republican presidencies, meanwhile, from 1921 to 1932, was Andrew Mellon, the Pittsburgh banker who had funded so much of the industrial development of the past several decades. He was the one largely responsible for the financial policy of this era, which he called “scientific taxation”. The federal income tax era had begun under Woodrow Wilson, and it was progressive, not in the political sense (though it was that, too), but in the sense that the tax rate became progressively higher for larger income brackets. The poor were overburdened by the financial system, and this was a method of relieving that inequality. But already under Wilson, people could see the progressive income tax didn’t work as expected, since the rich found non-taxable ways of protecting their wealth and economic development wasn’t being encouraged as before. The idea that Mellon championed, and it’s worth mentioning it was a non-partisan idea, was to cut taxes without diminishing revenue by encouraging economic development and decreasing incentive for evasive wealth management. The trick was to optimize revenue by reducing government interference, and thereby fostering progress. The idea of what counted as progressive reform was turning inside out. Government was strategically returning power to commercial interests.

Some would point to this moment as the beginning of supply-side economics, but that idea wouldn’t take shape for another fifty years. Now, I believe the economic principles of supply and demand operate according to the polarized pattern of thymos and epithymia — except in this case the poles are so contained within each other, I can’t tell which is which. Each of supply and demand have thymic and epithymetic qualities to their behavior. Without venturing into the economic weeds (which admittedly I’m not qualified to do), I think it’s safe to say government and commerce work according to the guardian-trader dialectic identified by Jane Jacobs, which (in my treatise) I have identified as the psychological polarity of thymos and epithymia writ large. The Progressive Era before the twenties, what with all its trust-busting, had been about government imposing itself on commerce in order to reign in the excesses of epithymetic appetite by means of thymic control. That was what social progress required, and the movement had to it also a moral dimension, as seen in the prohibition of alcohol. In the twenties, however, progress required a relaxation of government’s thymic control for the sake of the nation’s appetite for economic growth. Amidst the deference to epithymia, material desires flourished, and, under the strictures of Prohibition, impetus for moral reform lost favor. The rise in cupidity on the stock market, meanwhile, meant increasingly wild speculation. It was a time of decadence. It was not destined to last.

Coolidge’s Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover was a highly qualified candidate to be president in the 1920s. For the 1930s he was ill suited. The stock market crashed in October 1929, instigating, over the next two years, a run on banks that induced the Great Depression. The whole Progressive Era launched out of the depression of 1893; now it was collapsing back into the same, except much, much worse. President Hoover, using the thymic powers of the government, took many measures to solve the crisis that were in line with the progressive ideology of how to behave in times of commercial malfeasance. The Fed lowered interest rates. Hoover raised protectionist tariffs. He disciplined the banks and provided government loans for financial institutions, local governments, and farms. He and Andrew Mellon reversed course and returned the progressive income tax to where it was before. Hoover even signed a large public works bill, the Emergency Relief and Construction Act, in 1932. Nothing worked, as he and congress could not meet the vast scale of the problem they faced. The Republican party, dominant since the Civil War, was blamed for everything, and they would not be trusted to lead the country for a long while. Anyone the Democrats nominated could have won the presidency in 1932. The one they did, once in office, swerved away from all previous American ideas of what government should be, and the ensuing realignment radically changed the political parties and inaugurated the omega-chapter of U.S. history.

Ω. The Fifth Party System (1932–1980)

New Deal Democrats v. anti-communist Republicans

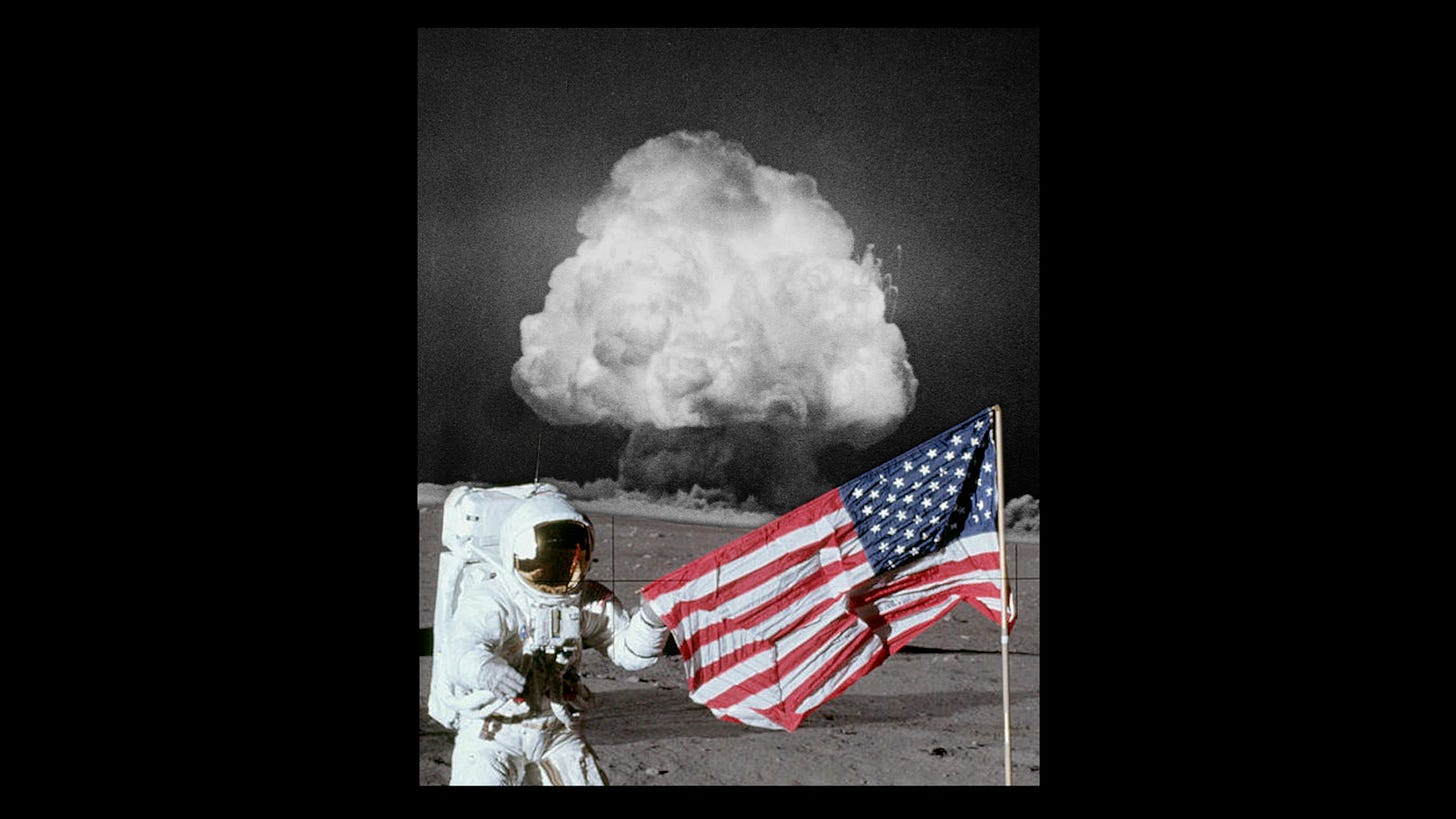

The apocalyptic Fifth Party System, born in reaction to the Great Depression, comes to be known as the New Deal era and the Cold War era — the Atomic Age is an another relevant moniker. I will need to demonstrate in the course of my narrative how it all fits the omega-symbolism of the cosmic chiasmus, but as I am less likely to have to explain to my readers who this era’s political leaders are, let me begin with the structural outline of the period.

In 1932 Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran a blandly Democratic campaign with little substance behind it, his victory being ensured by the deluge of negative partisanship against the Republicans. The “New Deal” was an empty phrase ginned up by his campaign; it had no policies attached. Once in office, he began to fill it in, and quickly so, with a vast amount of government activity that had no partisan content relative to anything that had come before. The idea of Roosevelt’s New Deal came to be creating a federal bureaucracy of non-partisan experts that by means of well-studied reason would dispassionately manage how society worked in most aspects. Accordingly, political polarization was abnormally low between the two parties for an historic amount of time, aided immensely by external polarization with the Soviet Union for the duration of the Cold War. I’ve labeled this system “New Deal Democrats v. anti-communist Republicans”, but that’s only because “New Deal, anti-communist Democrats v. anti-communist, New Deal Republicans” is too long a title. Democrats spearheaded the New Deal domestic agenda and, when they had to, initiated the opposition to worldwide communism; the Republicans joined in both projects, the latter more zealously than the former in that it correlated more strongly with their thymic drive.

In a sense, this era was the triumph of the Enlightenment reason upon which the country was founded. The elites held the reins of the chariot and kept the horses of polarization working in the same direction. The United States of America reached the height of its power as the most dominant country in the world. Only the amount of inequality, corruption, and bloodshed necessary to accomplish this greatness would lead one to believe this period was anything less than the Camelot of the Kennedy White House, superficially perceived. As the Cold War dialectic of rebellious reason triumphed over the world, its offspring the passions of desire and anger wrought an insurgency of their own, as the mid-twentieth century was inflamed with the sexual revolution, a rise in crime rate, and the deadliest outburst of global warfare that has ever been seen.

It’s not that the New Deal didn’t meet any political pushback. It certainly did. The economic strategy decided upon by FDR and his experts — besides adjusting the gold standard to increase cash flow, and also reforming banks with the Glass–Steagall Act, creating the FDIC — was the very opposite of the anti-trust activism of the previous era’s progressives. Whereas Teddy Roosevelt broke up trusts in order to increase competition and lower prices, the New Deal intervened to eliminate competition and foster collusion between companies so as to raise prices. From the consumer’s perspective this policy appeared more disastrous than anything else, but consumers are also workers; the objective was to improve the health of the companies on the condition that they retain employment and improve workers’ conditions. To this end, only large companies were fostered, or else smaller companies had to collude together as if they were large companies, collusion that the government facilitated. The experts wanted a system they could control, for which purpose economic powers had to be consolidated. The decentralization of small businesses, and their effect on the larger economy, had to be eliminated. The powers of government being enacted far exceeded the limits set to it by the Constitution, as the New Deal ventured into territory the Founding Fathers clearly would have identified as tyrannical. Indeed, the main arm of this meddling, the National Recovery Administration (NRA), was judged unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and shut down after two years of operation.

So there was pushback from the courts, and there was pushback in congress; but it was never along party lines. Roosevelt stacked his bureaucracy with experts from both parties, and fielded opposition from within both parties. Given an opportunity to support a Republican in favor of his policies in an election against a fellow Democrat who didn’t support his policies, Roosevelt would keep mum, retaining at least that much loyalty to his party. Effectively, by keeping any one party from aligning totally in favor of his New Deal, he also kept any party from aligning against it, greatly increasing its odds for survival. In the First New Deal of 1933–34, Roosevelt enacted many hard measures that could not maintain the public goodwill extended to them upon introduction. The vast preferential treatment of big businesses was abused by the wealthy beneficiaries, and when an independent commission exposed this, it was shut down and silenced. Enforcement of the NRA codes on less fortunate people trying to get by, moreover, could frequently wax draconian. What was even more optically challenging, to keep agricultural prices aloft, whole crops would be spoiled or otherwise destroyed according to government directives, specifically at a time when many people were going hungry — all of this by expert design for the sake of economic recovery. Times were dark!

In the Second New Deal of 1935–36, Roosevelt pivoted to shore up all populist criticism, focusing instead on unemployment relief and entitlement programs. These included the Social Security Act, the Works Progress Administration, and the National Labor Relations Act — the latter of which performed some of the roles of the defunct National Recovery Administration, except it consolidated power in the form of labor unions instead of businesses. Big business did not in the least care for the change in direction, but their lack of support was compensated for by voters in the 1936 election, ushering Roosevelt into a second term by a landslide.

The president’s attention then turned to the courts which had been frequently frustrating his agenda with their rulings. He threatened to expand the Supreme Court by several justices so as to pack it with those favorable to his policies. The Constitution doesn’t stipulate how many justices can be on the Supreme Court, so the threat was feasible. It nonetheless was seen as an attempt to breach the constitutional separation of powers, and it garnered much resistance, including from Roosevelt’s own vice president. A 1937 judicial reform bill failed in congress, but the president kept the pressure on by means of public radio address. Meanwhile Justice Owen Roberts switched his deciding vote in a minimum wage case so as to produce a result favorable to Roosevelt, widely seen as a capitulatory move to appease the president and preserve the integrity of the Supreme Court. Eventually Roosevelt got to nominate a justice of his own for the first time in 1938, and his wrath with the courts began to abate once he could shape its membership. By 1941, the first year of his unprecedented third term, he had named in quick succession seven of the nine Supreme Court justices. A new vision of what the Constitution could accommodate was established — not by amendment, but by changing the interpreters.

The resistance to the New Deal in congress, meanwhile, came to form a “conservative coalition” in response to the court-packing threat, a movement that would have defensive legislative successes but failed to gain any real traction for the duration of this party system, which is largely characterized by its lack of party polarization. World War II presented the first dampening effect, as the conservative coalition, comprised of Democrats and Republicans, were fully on board with Roosevelt’s war efforts. Immediately thereafter began the Cold War with erstwhile allies the Soviet Union, again a unifying force in American politics. After Truman’s narrow victory in 1948, the New Deal Democrats were set for a full twenty years in power. Come 1952, however, it was time for the Republicans to decide what role they were going to play in this party system.

President Truman had initiated a U.S. doctrine of contravening any communist incursions in the world, starting in Greece and Turkey, the Greek Civil War being the first proxy conflict of the Cold War. Intervention in those cases involved financial and military aid, but not full-scale troop deployment. That changed in 1950 when Truman engaged the U.S. military in the Korean War via the United Nations (without a congressional declaration of war). The fighting did not transpire favorably and was ongoing at the time of the 1952 presidential election. It’s also worth mentioning this had also been the McCarthy era, when Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, as well as the House Un-American Activities Committee, chaired by Democrat John Stephens Wood in the House, led demagogic witch hunts against communist infiltration of government and media. It was a time of abiding discontent.

Five-star Army General and hero of the European theater of World War II Dwight D. Eisenhower entered the Republican primary for president to oppose member of the conservative coalition Robert A. Taft, a senator from Ohio (and son of former president William Howard Taft). Besides opposing the New Deal, Taft also was isolationist, being opposed to membership in the United Nations or any involvement in Cold War–era police actions around the globe (except Israel, which he supported). Eisenhower felt the opposite, fearing any communist expansion anywhere, according to the “domino theory”, which in effect positioned communism on the high ground surrounded everywhere by slippery slopes. The convention battle between these two — preceding a general election in which the Democrats would not be nominating an incumbent for the first time in two decades on account of Truman’s historically high disapproval ratings — was a fierce competition for the soul of the party and of the two-party system going forward. Taft was accused of stealing some delegates from Eisenhower, as a result of which the convention voted to strip some delegates from Taft. In the end, the moderate, interventionist Eisenhower defeated the conservative, isolationist Taft by a narrow margin. The popularly successful two-term presidency that ensued offered proof that the party had made a good decision in not going the conservative route.

Eisenhower as president did nothing to roll back New Deal bureaucracy, even expanding its popular programs, confirming it as the new national normal, while at the same time ensuring the interventionist role the U.S. would play in the world thereafter. On the surface, Eisenhower campaigned for peace, accepting the armistice in Korea without further escalating war with China, and seeking to decelerate the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union (unsuccessfully). Covertly, though, by means of the CIA, Eisenhower authorized regime changes and assassinations in places where communism was making inroads such as Iran, Guatemala, and the Congo. The Dulles brothers, CIA director Allen Dulles and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, were willing and capable collaborators advocating for covert actions boosting American imperial interests around the world — material prosperity trumping any and all democratic values. Indeed, Eisenhower’s fifties were a time of tremendous economic growth for the U.S., with a newly built infrastructure of interstate highways, airports, and suburban sprawl transforming the American experience.

Opposition to communism in the midst of such prosperity, like advocacy for the New Deal, cut across party lines and comprised a national consensus. Eisenhower’s administration set up the plans for the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, so as to overthrow Fidel Castro’s communist revolution. The next administration was left to carry it out (unsuccessfully); that would be John F. Kennedy’s, a Democrat.

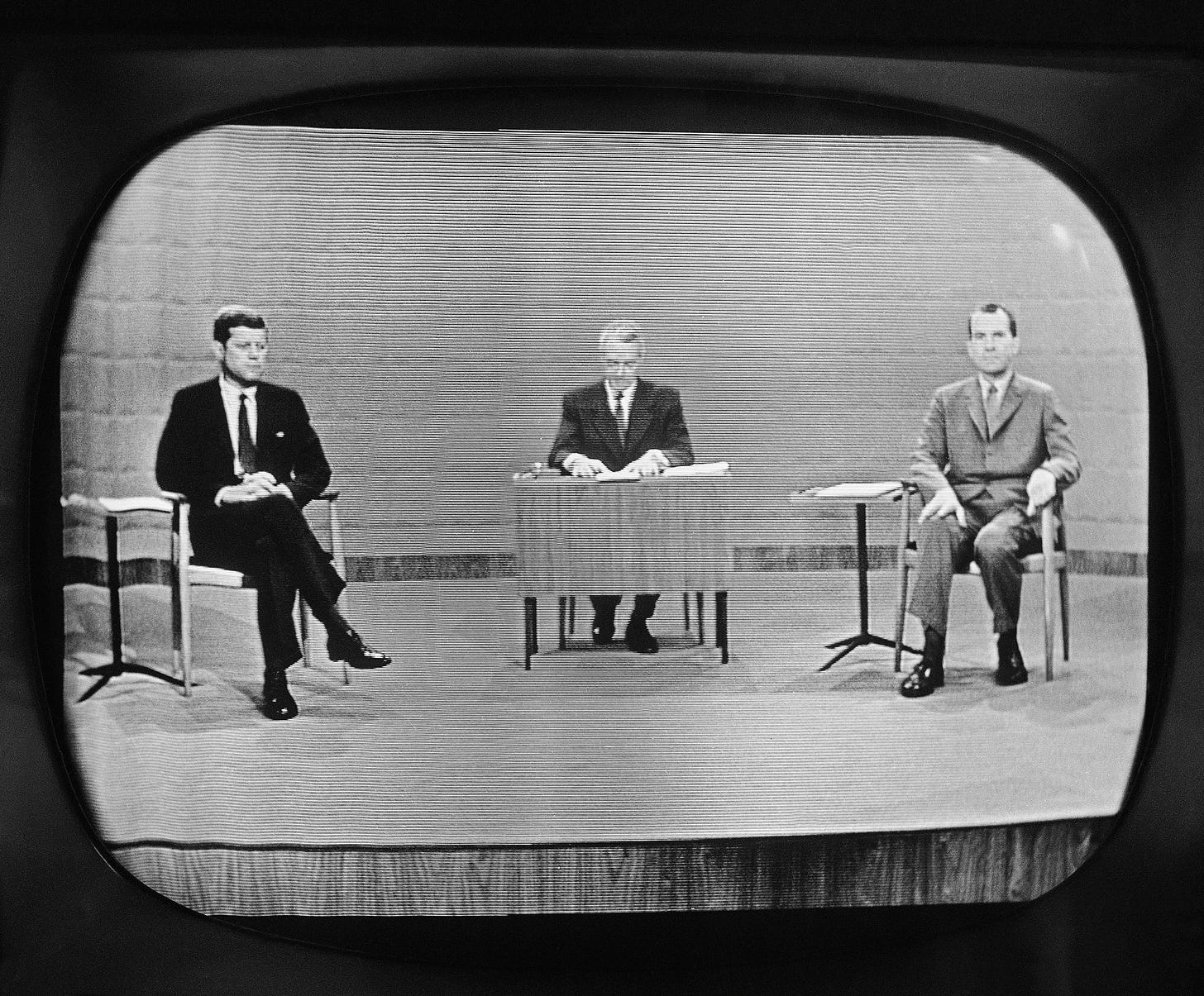

The pivotal 1960 election between Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard Nixon was tightly contested, with an extremely narrow margin in the popular vote. Either way, the U.S. was about to see one of its youngest presidents ever, and the first born in the twentieth century. There were presidential debates for the first time, four of them, and they were all nationally televised. The baby boomer generation coming of age was being conditioned to seeing their country’s history play out for them as a TV show. The more youthful, more attractive, more media-savvy Kennedy employed these advantages well. With the help of Texan running mate Lyndon B. Johnson, as well as of African American voters whose favor he won by helping spring Martin Luther King, Jr. from jail, Kennedy convincingly carried the electoral vote despite close calls in several states. Accusations of voter fraud abounded, particularly in Illinois and Texas, which two states alone would have swung the election had Nixon carried them — but Nixon refrained from contesting the results. His reasoning was to avoid a constitutional crisis and prevent setting a bad example for other democracies. American democracy must project strength, not weakness. The consensus of national identity at that time was just that much stronger than any partisan loyalty. What was the big difference between the two parties anyways?, a cynic well could ask. Regardless, as it happened, no evidence of significant voter fraud in this election was ever established.

We arrive now at the critical period of the sixties upon which the internal structure of the Fifth Party System hinges. It opened with the hottest peak of the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the United States and the Soviet Union came closest to thermonuclear war. The nuclear fission bomb was the fruit of the Manhattan Project, established under Franklin Roosevelt and deployed after his death in 1945 by Harry Truman, who used it twice on Japan in order to end the war in the Pacific. Truman developed further the even more destructive thermonuclear fusion bomb, or hydrogen bomb, first tested in 1952. From the beginning the Soviets had spies keeping them apprised of the advances, and they tested their own nuclear weapon in 1949, their own thermonuclear weapon in 1955. By 1962 both superpowers had parked such missiles in each other’s vicinities and were nigh about to use them. Tensions ran high for two weeks. Colder heads prevailed, and a new era began with increased communications between Moscow and Washington.

Domestically, the decade was one of great upheaval, with the passions of desire, anger, and reason all burning bright. Assassinations marked the beginning and ending, first with President Kennedy in Dallas in 1963, matched with his brother, leading presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, as well as civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968. JFK’s successor President Lyndon B. Johnson, meanwhile, brought the New Deal era to ever greater heights. So-called “task forces” comprised of experts once again rationally studied every aspect of society, and a broad range of legislation transformed the government and the nation anew, Johnson branding his agenda the “Great Society”. Famously the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 finally did the work the Reconstruction failed to do in ending segregation laws and forbidding discrimination in employment and voter registration. One could well argue how suboptimal it is, and potentially damaging, to achieve these gains via federal legislation, but it wasn’t happening without it. White racism had to be confronted with government force, just as a century prior slavery wouldn’t have ended without a civil war. President Johnson himself was bigoted against black people, but he went through with the legislation because he believed it to be a political necessity.

Other accomplishments of the Great Society will be too many to list, as with the New Deal before it. Medicare and Medicaid (health insurance for the elderly and the underprivileged, respectively) filled in the biggest gap of the New Deal with programs of abiding popularity. It henceforth would be the standard idea of American government that these entitlements be provided. Other elements of Johnson’s self-declared “War on Poverty” were less universally acclaimed. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, creating the Office of Economic Opportunity, became the centerpiece of a welfare state, making it the federal taxpayers’ business to lend a helping hand to those in need in a variety of functions. The Food Stamp Act of 1964 provided food subsidies to the poor. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 funded underprivileged schools and aimed to reduce achievement gaps. The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, to be administered by a new executive department of the same name, greatly expanded the federal government’s role in housing, providing subsidies for the poor and needy. The National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting were all created as ways for the publicly funded government to promote culture in ways the private market wasn’t.

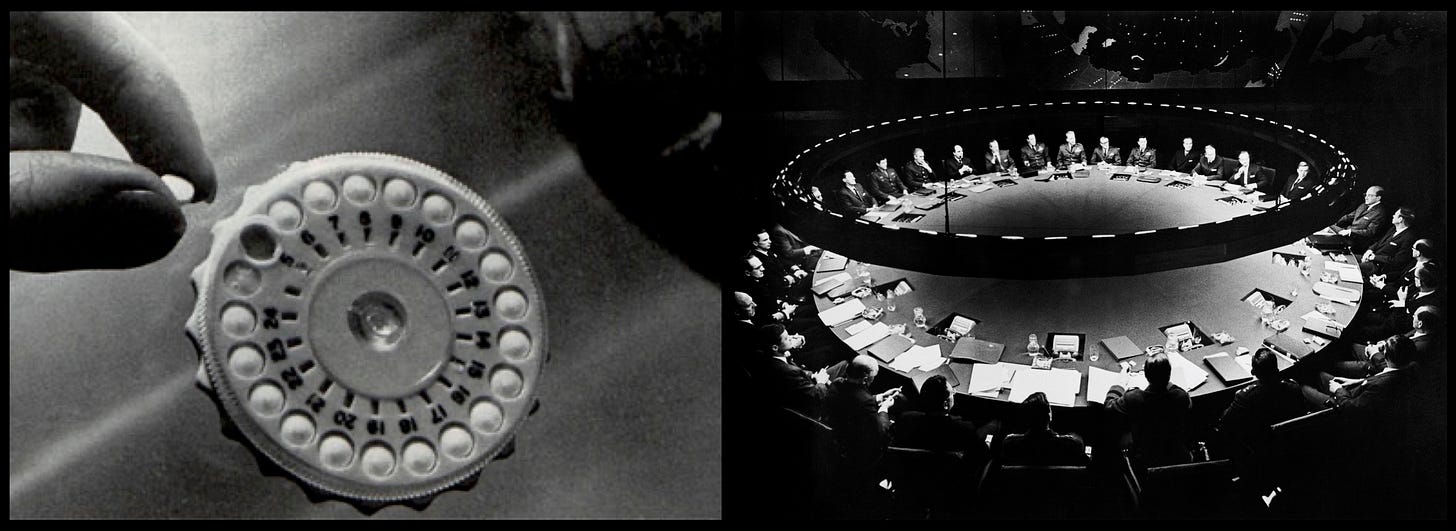

The Great Society, designed by experts, once again proved a triumph of Enlightenment reason, except it was now achieved in a time of economic growth and freedom rather than the dire straits of the Great Depression to which the New Deal was responding. Under the aegis of rebellious reason, then, unfettered by economic constraints, desire and anger were likely also to thrive, and they did. The birth control pill first went on the market in 1960, and it wasn’t long before millions of women in the United States were taking it. Adults having spent their formative years in suburbs and cities centered around capitalist marketplaces instead of around temples were wanting to explore their sexuality for the sake of self-pleasure rather than sacrifice, many turning to pharmaceutical technology to insulate themselves from nature. It was a sexual revolution based on the inflammation of desire. And as with epithymia, so with thymos. Rates of crime and violence rose even as the population grew. But no violence was greater than the proxy war in Southeast Asia into which the rational experts in the Defense Department plunged the country.

Serving as Secretary of Defense under both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, Robert McNamara practiced a highly rationalized method of systems analysis for determining policies and making decisions. It had served him well in the Army’s Office of Statistical Control during World War II, as well as at the Ford Motor Company after the war, where he pioneered the use of computers in business management. Kennedy resisted embracing his hawkish recommendations in Southeast Asia, the president’s resolve having been shaken by the Bay of Pigs fiasco in Cuba. In Johnson, McNamara found a more willing collaborator. In 1964 the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was passed by congress authorizing the president to use military force in Vietnam. Congress never declared war on North Vietnam, so this resolution was the basis of all war activity in the region going forward — but it itself was based on an incident, an attack, that in fact never happened, which Johnson knew and McNamara later admitted. The U.S. proceeded to involve itself, nonetheless, in a brutal, senseless, and unwinnable civil war in Vietnam, as determined to be prudent by McNamara’s rational analysis. By Johnson’s last year in office, 548,000 American troops were at war in Southeast Asia, and some 30,000 had died there. A large majority of them had been volunteers, but a rise in conscription rates had a lot to do with encouraging people to join, so as to control in what capacity they did so. Drafting young men into a dubious war with death tallies mounting daily became a point of polarized dissent. As years passed, domestic unrest began boiling over.

And yet, party polarization was still low. Those rebelling from the Democratic war efforts didn’t have the Republicans to turn to, certainly. Also, neither could those rebelling from the Democratic welfare state turn to the Republicans — though they did try. By the time the Great Society got underway, all conservative resistance in congress had been overcome. But at the same time, in the 1964 Republican presidential primaries, a homewrecking adultery scandal worked to tank frontrunner Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York and member of the Eastern elite indistinguishable from Democrats. In his place rose the insurgency of the Barry Goldwater campaign. Over the previous decade a verifiable conservative movement, opposed to big-government New Deal bureaucracy, had appeared among young, highly engaged activists who had as a guiding light the ideas of William F. Buckley, Jr. and his periodical National Review (founded in 1955). The nomination of Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater as the Republican candidate for president was their crowning achievement. Here in the center of the Fifth Party System, there was emerging an opportunity for real polarization around the central ideology of the era. It was roundly rejected. Goldwater was crushed in the general election, and Johnson used the landslide victory as a launching pad for the most ambitious programs of his Great Society. Republicans learned their lesson and in 1968 returned to the accommodating policies of the Eisenhower administration, again nominating his vice president, Richard Nixon. The Cold War era of the Fifth Party System was to be a time of conformity, rejecting any polarization not directed towards the Soviet enemy.

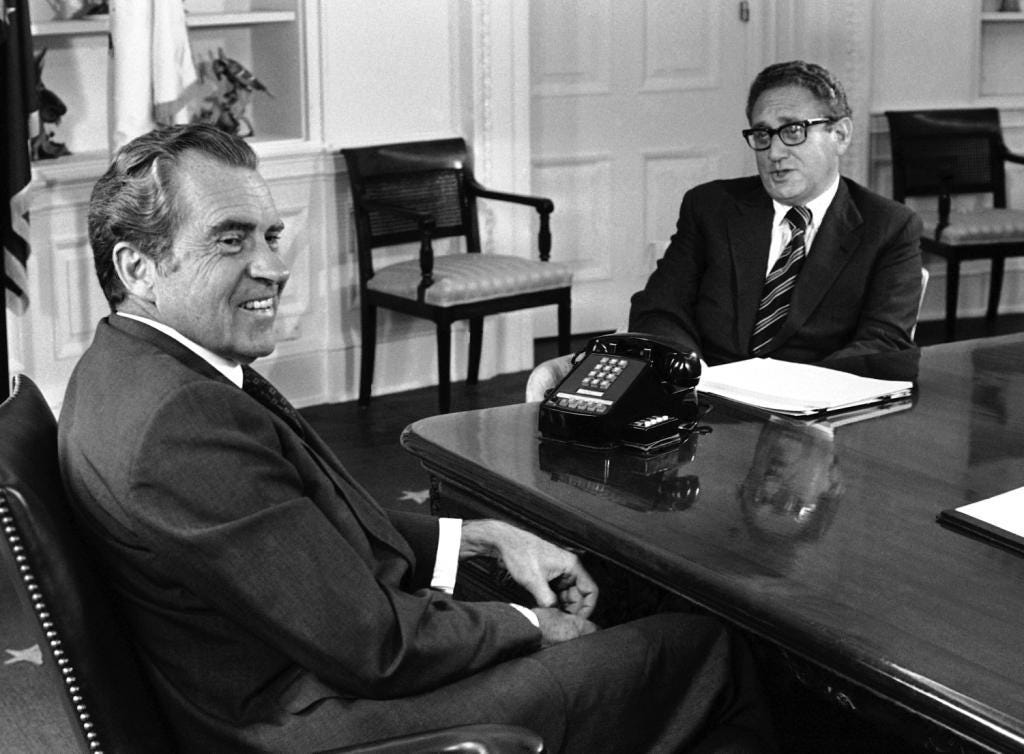

Howbeit Nixon was a polarizing figure. In ’68 he campaigned and won under the banner of “law and order”, which any rational candidate would do in a time of such rising crime rates, civil unrest, political assassinations, running tallies of war casualties, and continual televised violence (this was also the year of the My Lai massacre and of the riots of police brutality towards protesters at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago). Nixon accordingly also campaigned with the promise of ending involvement in the Vietnam War, which was as popular an idea as “law and order”, but also an economic priority since the weight of the Great Society plus the cost of war was causing annual budget deficits and a high inflation rate that was dragging down the economy. Once in office, however, Nixon struggled to extricate the nation from the quagmire of war, failing to do so for multiple years and engendering great resentment. The Kent State massacre in which the Ohio National Guard shot at unarmed war protesters on a college campus, killing four and wounding several others, happened under his watch in 1970. His war with the press, moreover, which was unveiled not to his favor in the Watergate scandal that would lead to the premature end of his second term in office, added to the impression of him in the burgeoning liberal imagination as a thymic tyrant. This memory belies his record, however, as a synthesizer of all the major themes of Fifth Party System (not just thymic tyranny).

As with Eisenhower and the New Deal, President Nixon accepted the popularity of the Great Society, not rolling it back and even expanding upon it, serving the epithymetic appetites of the welfare state at the same time that he was signaling thymic control through rhetoric of law and order. He created the Environmental Protection Agency and continued Johnson’s trend of environmental legislation. He created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to regulate and inspect for safety workplaces such as factories and construction sites, initiating a very conspicuous presence of the federal government in many people’s lives where it hadn’t been before (and making workers’ conditions significantly safer). He supported the Equal Rights Amendment, designed to end discrimination based on sex, when it passed through congress (it was never ratified by enough states to make it constitutional). He oversaw the desegregation of schools, according to the previous administration’s civil rights laws. Also inheriting the space race, he kept with NASA’s lunar ambitions through seven trips to the moon (and six landings) between 1969 and 1972.

Nixon also entirely remade the global economy by suddenly and without warning detaching the American dollar from the gold standard. This was a highly deliberate maneuver that was extremely difficult to pull off politically and very risky, but it was successful in everything it set out to do and was considered a major triumph at the time (in 1971). Its legacy is decidedly mixed, but no doubt alive and well, as ever since the American dollar has been a floating currency with no fixed value and no basis in any commodity. All other global currencies had to adapt by becoming likewise. Certainly it’s hard to imagine administering the debt-based spending habits of American governments committed to big bureaucracies and massive militaries without the flexibility of a fiat currency based on nothing but a collective imagination. In his law and order rhetoric, Nixon regularly criticized what he saw as “permissiveness” in contemporary morals, but what he did to the American dollar I think can best be described precisely as “permissiveness”; it was a concession to the government’s appetite for overspending and his inability to end the war.

But Nixon did what he thought he had to do in order to lead the country it was his ambition to lead. Decidedly the focus of his presidency in that regard was on foreign policy. Here we see an interesting turn in the dialectic of polarization. Nixon came to power when the nation was being ripped apart by the polarity of desire and anger, ironically a condition created at the height of societal control by rationalist experts. The unifying polarity of opposition to communism was breaking apart with the unpopularity of the Vietnam War. But Nixon began smoothing relations with our communist foes, both in the Soviet Union and in China, both of which he visited, initiating a period known as détente. First Nixon shockingly befriended Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong of China, visiting there in February 1972 after National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had covertly laid the diplomatic groundwork. They (Nixon and Kissinger) knew the prospect of alliance with China would force the Soviets to the negotiating table, and it worked. The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) were signed at the Moscow Summit later that year. Then in the early months of 1973, at the start of Nixon’s second term in office, he and Kissinger finally managed to withdraw U.S. troops from Vietnam, though they failed horribly at ending the civil war there.

That year, 1973, Nixon’s vice president Spiro Agnew was found to have long been accepting bribe money, was pinned with tax evasion, and was forced to resign. In his place Nixon appointed the House minority leader Gerald Ford, a representative of the same district in Michigan for the past 25 years, known best of all for being inoffensive. Nixon himself would be forced to resign on account of the Watergate scandal the next year. Hence Gerald Ford, whose greatest ambition had been to be Speaker of the House, and who had never won any election besides in his district in Michigan, became the President of the United States. He inherited Nixon’s administration as well as the ongoing recession which precipitated from the end of the gold standard and the rise in oil prices by Arab countries retaliating against those who supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. This recession was the worst since the Great Depression and marked the end of post–World War II economic expansion. It was the first appearance of “stagflation”, the combination of high unemployment rates with high inflation. Ford’s attempts at addressing the issue were clumsy and ineffective. His greatest legacy might just be saying upon his inauguration, “Our long national nightmare is over” — a phrase that somehow already sounded sarcastic the moment it was uttered. He did create special education for disabled children, throwing another log on the fire of the Great Society; there is that.

But Ford also continued Nixon’s foreign policy and raised up a new generation of leaders in the spirit of the “Kissinger Report”. The Kissinger Report (officially National Security Study Memorandum 200) was a classified document ordered by Nixon and completed under Ford, drafted by state department official Philander Claxton, Jr. under the direction of Henry Kissinger, who at this time was both National Security Advisor and Secretary of State. The focus of the report was the acceleration of global population growth, viewing it through the lens of the national interests of the United States. Its conclusion was that population growth, particularly in underdeveloped countries, presented a deep threat to the hegemony of the United States in that it could interfere with the extraction of their resources. It recommended taking measures to reduce fertility rates globally, including in the United States, as a way of concealing the imperialist objective of reducing the population growth in the poorer countries specifically. The methods recommended included contraception, abortion (granted legal protection in the U.S. by the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade in 1973), and sterilization, the promotion of which was to be tied to receiving foreign assistance through USAID (the United States Agency for International Development).

President Ford adopted the ideas of the Kissinger Report as official state policy in a decision memorandum of his own in 1975. As a result the use of contraception and abortion, and in some cases sterilization, were promoted through USAID. These memoranda remained classified for fifteen years and were not known publicly. The “spirit” of the Kissinger Report that I mentioned — and I think we can see it has been the spirit of U.S. foreign policy throughout the Cold War era and beyond — is promoting the material benefit of the United States at the expense of all other values.

The Republicans stuck with Gerald Ford as their candidate for president in 1976, despite a robust primary challenge from Goldwater-esque conservative Ronald Reagan, recent governor of California. It wasn’t Reagan’s time, but it wasn’t Ford’s either. Ford had pardoned Nixon, on account of which he was fated to play out the rest of the term in office he had inherited and then disappear from power like the man he pardoned. Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter, recent governor of Georgia, benefited from that stigma, but still only barely edged out Ford in the general election. After Vietnam and Watergate, it was not a time of great political enthusiasm in America. Fittingly, neither candidate was very attractive.

Carter scored his nomination from the Democrats on account of changes they had been making to the primary process ever since the disaster in 1968 when their leading candidate was killed in June, their convention provoked a violent riot in August, and they lost to Richard Nixon in November. Primary voters now had a larger say in who would be nominated, as opposed to the party elite who previously could pick among themselves. Senator George McGovern of South Dakota was the first beneficiary of the rule changes in 1972, becoming the liberal, epithymetic version of Barry Goldwater, a polarizing figure according to the politics of a subsequent era; McGovern advocated for the legalization of abortion and marijuana, for example. The Fifth Party System would have nothing of it, and McGovern lost worse than Goldwater, winning but 17 electoral votes to incumbent Richard Nixon’s 520. (And that was before Nixon managed to withdraw troops from Vietnam.)

Governor Jimmy Carter in 1976 was even more of an outsider than McGovern, on account of which he appealed somewhat to disaffected voters, but on account of which he had not been vetted by the insiders with whom he’d be working in Washington. He was more electable than McGovern, being a Southern Evangelical; in fact, Carter was the first political candidate to motivate Evangelicals as a voter base, something that would become a common theme going forward (though never again in the Democrats’ favor). Once he was president, however, Carter immediately got off on the wrong foot with congress, particularly with those of his own party like Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, the kind of elites whose preferences had been sidelined in the primary process. The president and congress were in constant acrimony, and Carter’s administration would be known for its lack of accomplishments.

The United States was still the most powerful in the world — and yet the economy was in recession, inflation was soaring, the Arab countries had the U.S. over a (petroleum) barrel, the crime rate was soaring, divorces were commonplace, pornography was going mainstream, children were not safe — everyone was dissatisfied. “Malaise” was the byword of the era, and it was all pinned on an ineffective Jimmy Carter, who often gave heartfelt, moralistic speeches that never amounted to any positive action.

Man, could that Evangelical speak, though. He was so dearly honest. A lot of hard truths were relayed in his messages to the people, some that bring a tear to my eye to hear them spoken aloud by a man in his office, even if his liberal humanist faith undermined everything true that he said. It may be perverse, in my internal structure of this party system, to match chiastically the unparalleled might of Roosevelt and Truman’s twenty-year reign with the depressing malaise of Carter’s single term, but the contrast says something important about what happened to the instigating idea of this era and the Democrats who led it. The apotheosis of Enlightenment reason enacted in New Deal America with its rule by scholastic experts was bound to end in “paralysis and stagnation and drift,” as Carter put it in his famous “Crisis of Confidence” speech at the height of the oil crisis in 1979 (see embedded video below). Stagnation signifies a lack of movement, and drift a movement that cannot be steered. The combination of the two recalls the anxiety of an immobile incensive power and the despair of an unbridled appetite, two poles at either end of an impassioned magnet that both tears apart and restrains in place. Paralysis, for its part, as with a charioteer who has forever lost hold of his reins (or as a president that has lost use of his legs), is the end condition of the rebellious reason that sees clearly the flaring polarization of stagnation and drift and can do nothing to stop it — very much like Carter as president.

Carter knew the problem was spiritual. “All the legislation in the world,” he said, “can’t fix what’s wrong with America.” As if in response to the spirit of the Kissinger Report, he said,

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

He acknowledged the damaging effect on American’s self-confidence caused by the political assassinations, the agony of Vietnam, the shock of Watergate, the decade of inflation shrinking people’s savings, and the humiliating dependence on foreign oil. He then described how we should respond: “First of all, we must face the truth, and then we can change our course.” He wanted Enlightenment reason to reclaim its throne over the destructive passions. But it was precisely the false god of reason that led the nation to where it was. “We simply must have faith in each other, faith in our ability to govern ourselves, and faith in the future of this nation,” the humanist preached, futilely. Notice the Nietzschean emphasis on the nation’s future, uncreated self. “We’ve always believed in something called progress. We’ve always had a faith that the days of our children would be better than our own. Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy.” Humanity’s faith in itself historically is built on its doubt in God. Once it raises itself up to the level of God, it can only then have doubt in itself. Reason, once basing its knowledge in doubt, can only collapse back into doubt in the end.

“We are at a turning point in our history,” he said, truthfully, reminding me frankly of Washington’s Farewell Address.

There are two paths to choose. One is a path I’ve warned about tonight, the path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest. Down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom, the right to grasp for ourselves some advantage over others. That path would be one of constant conflict between narrow interests ending in chaos and immobility. It is a certain route to failure.

The other path he would go on to identify, to which “all the traditions of our past, all the lessons of our heritage, all the promises of our future point,” was a false one, another “mistaken idea of freedom”, the very path of self-belief and rebellious reason that led the nation exactly to where it was. Ineluctably then, that first path he described, calling it a warning, was in fact the solemn prophecy of the party system to come: “...chaos and immobility...”, “...a certain route to failure.”