The sequence of party systems in U.S. political history, part 1

Jumping into the octave pattern unprepared — but we’ll learn as we go

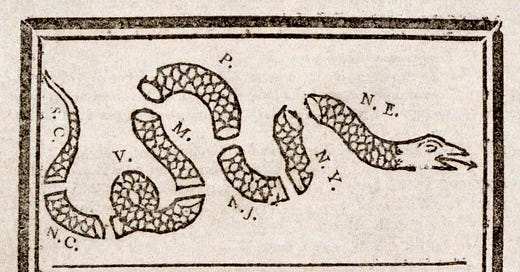

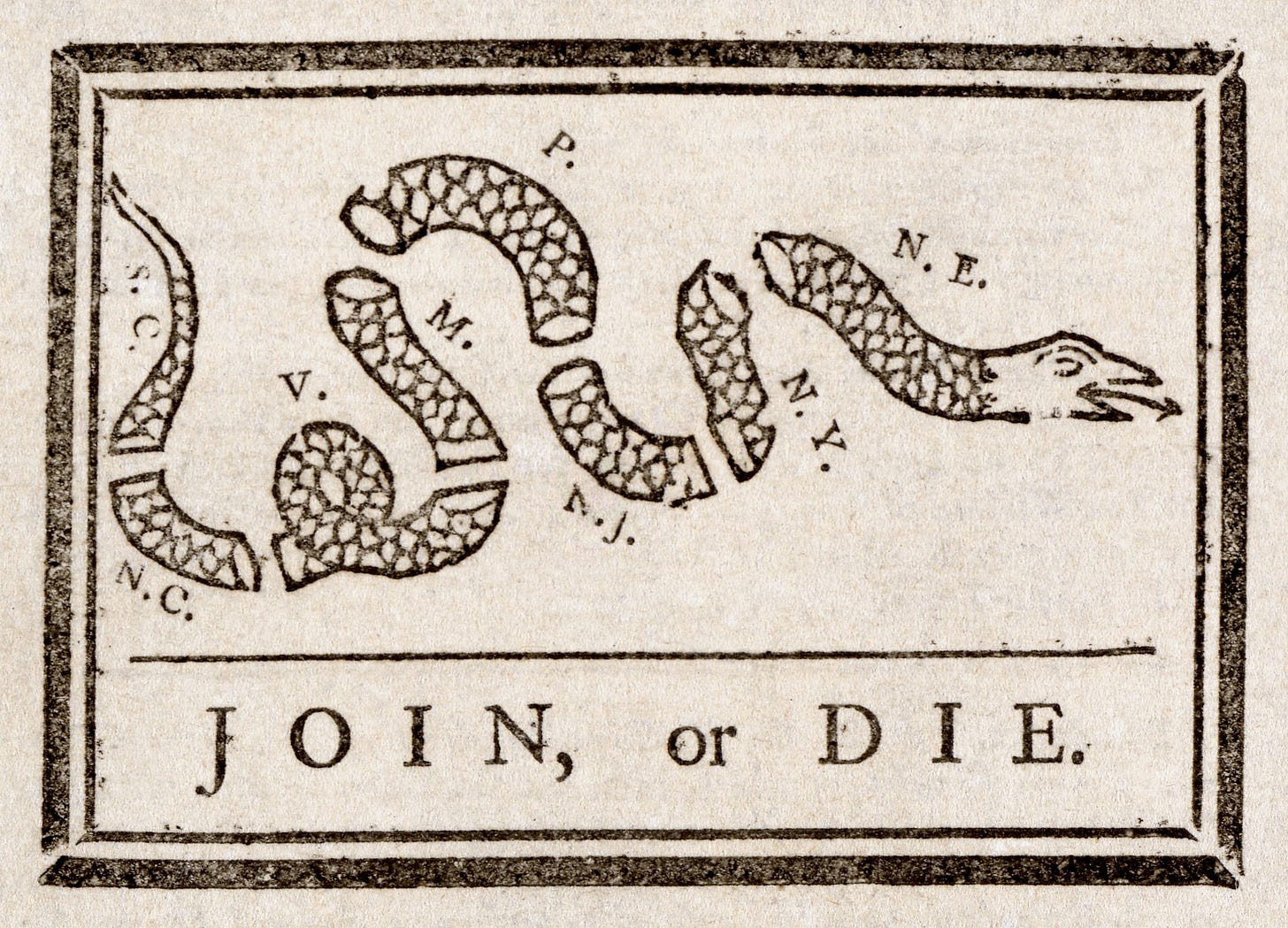

The famous “Join, or Die” woodcut political cartoon — which I have chosen here to lead this, the follow-up to my big political treatise — first appeared in the May 9, 1754 edition of The Pennsylvania Gazette. Commonly attributed to Benjamin Franklin, it was made as propaganda in the lead-up to the French and Indian War. The four colonies of New England are here represented together as one; Delaware at that time shared a governor with Pennsylvania; and the highly unregulated colony of Georgia was not invited to the party and left for dead (sorry, Georgia!). Hence the thirteen-colony serpent, an image reused at various times during the independence movement, is sectioned in eight parts — a convenient image for my eightfold history of the United States. Reading from left to right, the composition even makes sense visually according to the octave pattern that I will here lay out.

Another option I had for the lead image was the pine tree flag, the emblem used by warships commissioned by the rebelling Continental Army in 1775:

“An appeal to heaven” was an allusion to a well-known passage in John Locke’s Two Treatises on Government. It referred to the inborn right of the people to appeal to a higher power whenever their inborn rights were not honored by earthly powers. Though the imagery is vaguely Christian, the ideology hinges on human rights as rationally perceived — it’s all Enlightenment rationalism in Christian guise. The heaven being appealed to must be understood as human reason.

Although in my political treatise last month I emphasized the polarization of the lower passions in determining the politics of right and left in the United States, in this current set of posts, as I trace out the eightfold history of my nation’s party systems, I will need to highlight the role of reason (logos) in the process. Reason is the charioteer of the lower passions. But in the rebellious elevation of reason over all anciently held authorities, the pattern of the succession myth is enacted: one god rebels against an older one only to be rebelled against by younger ones. Reason — the god of the Enlightenment — wishes to imprint itself on the lower passions of thymos and epithymia, and does so. It doesn’t see, however, how its rebellion is also included in the transfer of energy. If it wishes the lower passions to be obedient to it as a higher power, reason itself must be obedient to a higher power. Otherwise, our new Zeus is in trouble of no longer being worshiped, and its image in its inferiors will be chewed up and expunged. Reason, like Zeus, traumatized by being consumed and disgorged by a previous generation of false principalities, tragically seizes power in a way that condemns it, eventually, to being devoured and vomited by its own children. I see this story as the throughline of American history, but the dialectical process has taken some time to develop. This is a tale not simply of an evil principality getting its comeuppance, but of a nation that is both good and evil. As such, that which is good within it will receive all the time it deserves to breathe and have life, even amidst all the evil.

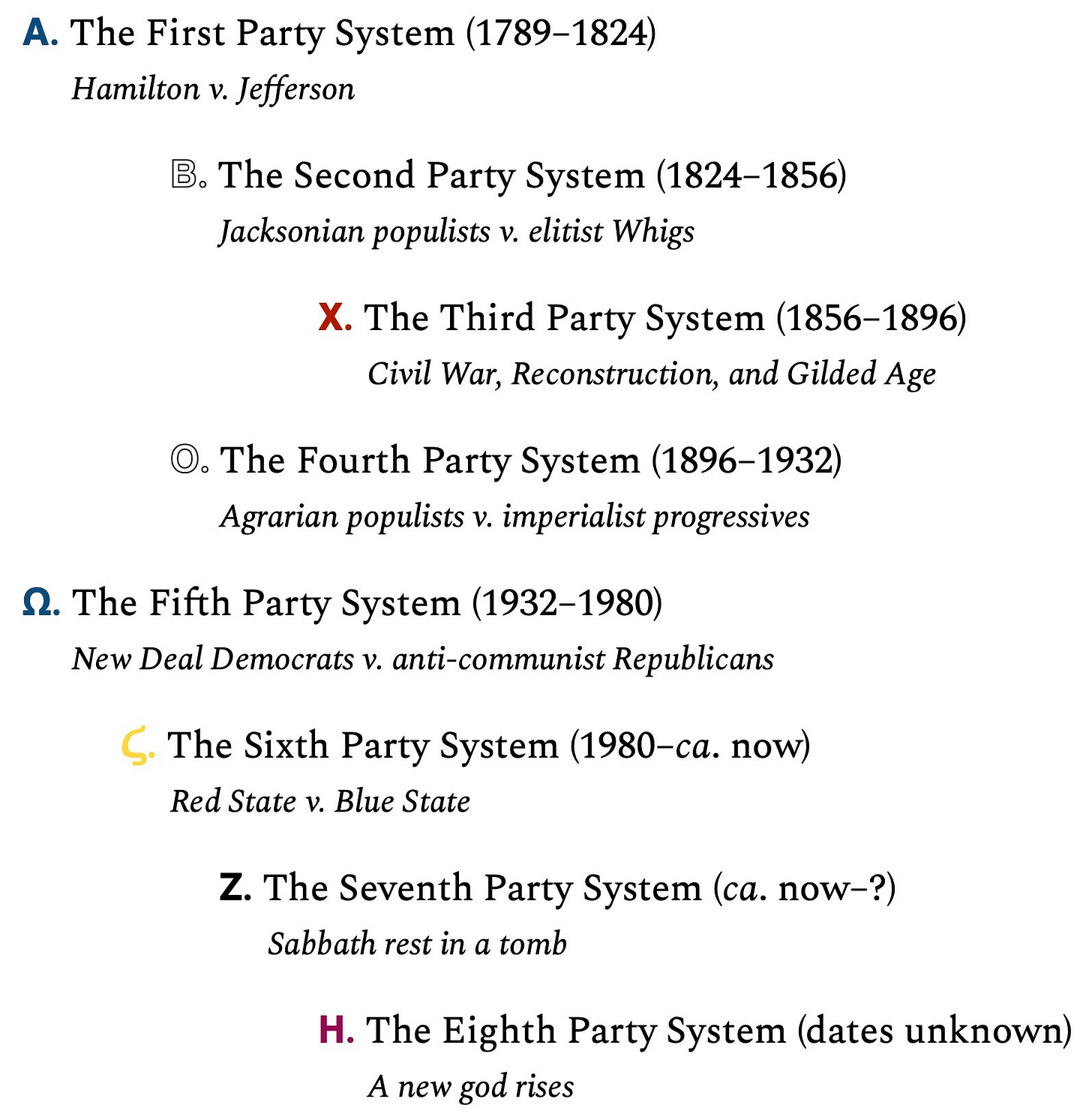

Here then is my outline of the party systems in U.S. history. It is based on a scholarly consensus of periodization, to which I am adding my own interpretation.

Α. The First Party System (1789–1824)

Hamilton v. Jefferson

As I described in last month’s treatise, General-turned-President George Washington argued stridently for the submission of the passions of party to reason. These passions, which I identify as thymos and epithymia (anger and desire), are an imminent threat to the republic if unleashed, Washington warned. And he held sufficient respect within his nascent country to contain polarization within his command while he ruled. Transitioning from the Articles of Confederation and its too weak central government, however, Washington’s administration naturally leaned heavily on the federalist side, as opposed to the anti-federalists who argued against the Constitution.

Among those who supported the Constitution, though, there was still plenty of room for disagreement over how strong the central government should be in relation to the constituent states. Primary authors of the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton of New York and James Madison of Virginia, for example, would find themselves on opposite sides of this magnet. Madison and his close partner in politics, fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson, represented those who would retain anti-federalist emphasis on state power within a Constitutional framework. Hamilton, on the other hand, as Secretary of the Treasury and chief ideologue of Washington’s presidency, successfully strove to consolidate state debt amassed during the War of Independence into one national debt, to be managed moreover by a national bank. Such a strategy gave great powers to the federal government and benefited commercial industry in the North at the expense of agrarian interests in the South.

When Washington stepped aside as president after two terms in office, the stage was set for the eruption of party conflict. Vice President John Adams of Massachusetts represented the Federalists, largely favored in the mercantile North, and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson represented the Democratic-Republicans, largely favored in the agrarian South. The election, that of 1796, was tightly contested and reflected the conflict ongoing in Europe at the time. The French Revolution, from which come the terms right and left as applied in politics, was front and center in American minds, as the Federalists were accused of the sins of the royalist French right and the Democratic-Republicans were accused of the sins of the liberal French left. Indeed the Democratic-Republicans were in favor of improving relations with Republican France, while the Federalists were quick to point out that the U.S. economy depended on relations with their primary trade partner, monarchical Great Britain.

The Federalist John Adams narrowly won in 1796, and his presidency greatly exacerbated the polarization. His Alien and Sedition Acts in particular repulsed his opposition. Forged against the background of an undeclared naval war with France, these acts curtailed free speech criticizing the federal government and were used against the administration’s Democratic-Republican enemies. A rematch between Adams and Jefferson was set for the 1800 election, and the campaigning was infamously acrimonious — with attacks as vicious as anything seen in American politics since. Once Jefferson won, however, and the Democratic-Republicans for the first time came into power, something strange happened. President Jefferson set out to dismantle Hamilton’s national bank, of course, but his Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin convinced him not to. Enough time had passed to validate all of Hamilton’s centralizing financial infrastructure. It was working beautifully. Jefferson accepted therefore a policy hitherto central to his political opposition, and the necessity of a national bank became commonly accepted by both parties for the remainder of this party system. (Madison, as politically opposed to Hamilton as anyone, once he was president allowed the bank’s charter to expire, only to charter a new one in its image.)

Jefferson also cut down the national army to half its size, believing state militias would suffice for defense. But he then had to found a national military academy at West Point in order to replace the Federalist officer corps with men more in line with Jeffersonian ideas. Polarization against the Federalists thereby drew Jefferson into establishing a key element of federalizing infrastructure. Similarly, he started his administration slashing naval spending, but at the same time engaged in what would become the nation’s first official foreign war, the First Barbary War, against state-sponsored Muslim pirates off the North African coast — a years’ long quagmire requiring Jefferson eventually to rebuild the national navy at great expense.

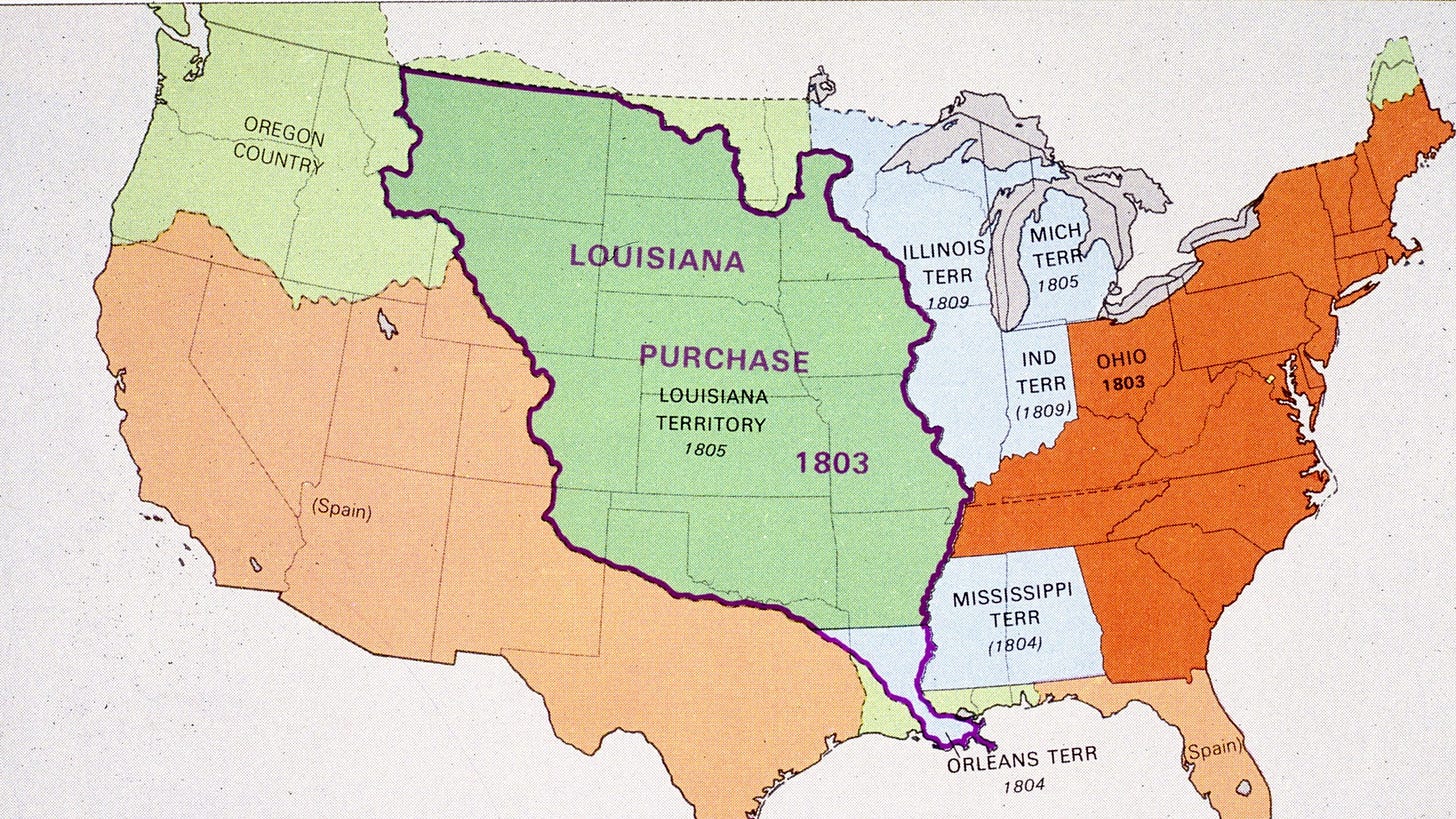

Then also, in the midst of his first term in office, the opportunity arose to buy from Napoleon exclusive colonial expansion rights into enough territory west of the Mississippi River to double the U.S. in size. For fifteen million dollars, Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. His friend James Madison, Father of the Constitution, assured him it was constitutional, but that it was so was not immediately evident to everybody. At the very least, this was a humongous flex of federal power. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that had Hamilton or Adams attempted such a thing, Jefferson would have been a vociferous opponent. As it happened though, he was the one doing the thing, and with enthusiasm, since expansion westward was likely to support his agrarian agenda, despite the flex of federal power necessary to do it. Federalists did in fact oppose Jefferson in the purchase, which had to be ratified and funded through congress, on the grounds that it was expensive and not necessary since France could not have defended its claims — and also just on the principle that Jefferson was a hypocrite. Indeed, Jefferson cut taxes and took other measures to limit government, according to behavior one would have expected, but in many ways his presidency was transformative to himself and his party.

The out-of-power Federalists, meanwhile, who increasingly were seeing their causes absorbed by their opponents, began lacking a reason to exist beyond the inertia of polarization. Their allegiance to peaceful relations with Great Britain, however, was one cause that stuck. In contrast, the fourth president, Democratic-Republican party co-founder James Madison, started the War of 1812 with Great Britain (which lasted, for the record, until February 1815). The Federalists gained some political traction in opposing the conflict, especially when the U.S. was doing poorly in it, but by the time General Andrew Jackson heroically won the Battle of New Orleans in the last month of the war, the demise of the party was in sight. The war ended in something of a stalemate, but to the Americans it felt like re-winning their independence. The effect was galvanizing and depolarizing. The so-called Era of Good Feelings ensued and continued throughout the two terms of the popular James Monroe, also of Virginia, also a Democratic-Republican. The great debates of the First Party System were all concluded. The Federalist Party had withered into non-existence — the party embodying George Washington’s political legacy had been inverted into a byword of villainy and betrayal. It was a time, unique in American history, of one-party rule. Polarization is inevitable, of course, but Monroe held it within his administration and his party like a second Washington.

The repetition of contained polarization brings me to the shape of the five presidencies of the First Party System. Helpfully, they arrange themselves into a neat example of the chiastic/ksiastic fivefold pattern I describe in “The Cosmic Chiasmus.” This shape forms the stable foundation of the octave, and so is worth reviewing here. As we’ll eventually see, the first five U.S. party systems, from the nation’s founding through the end of the New Deal/Cold War era, follow the same typological pattern.

I’ve basically already explained the chiastic narrative above, epitomized in the italic lines of explication. The central image here is of Jefferson crossing the Mississippi, and the boundaries of ideology, to double the nation in size of land claimed. The fivefold pattern of the whole, meanwhile, could alternately be contemplated as ksiasmus in that the War of 1812 during Madison’s presidency brought America back to feelings of the Revolutionary War symbolized by Washington, and also that the polarized acrimony of Adams’s presidency is contrasted with the Era of Good Feelings particular to Monroe. Also in favor of a ksiastic understanding, there is the plight of the White House in this era: It was constructed during Washington’s presidency, and then Adams was the first to move into it. Ksiastically, Madison saw it burnt down by the enemy (in the war that he started) and had to rebuild it, whereas Monroe, like a new Adams, was the first to move into the new White House. The internal structure of this first act of national history is very coherent and very sound.

Β. The Second Party System (1824–1856)

Jacksonian populists v. elitist Whigs

The Era of Good Feelings, contrary to its name, was fairly corrupt. Lacking a political opponent after the sad collapse of the Federalists, the Democratic-Republican party was ready to collapse as well for lack of purpose. The era’s “good feelings” were being had largely only by the elites in power, who funnily enough found they all agreed they should all be in power — and yet still jockeyed for position in less than ethical ways. It is easy to forget when we talk about bygone eras of U.S. politics who it was exactly that was responsible for doing all this politicking. The Founding Fathers, despite their arguments over state and federal power, were remarkably consistent in their disdain for the idea that anyone other than white, land-owning males could possibly be held accountable for the upkeep of the republic. Those less well-off, it was reasoned, would be corruptible by material incentives instead of being motivated purely by political principles like the Founders imagined themselves to be. This elitism, I believe, is modeled after Enlightenment psychology, whereby reason must assert its primacy and authority over the corruptible lower passions, which in turn are not to be trusted with any of their own power. This mentality, applied socially, created a caste system.

During Democratic-Republican hegemony in the early 1800s, however, suffrage began to be expanded state by state to those white males not owning land. Gradually the power to vote was being entrusted to those less wealthy, as no doubt with time the rational superiority of the rich appeared less obvious, and the relative moral dignity of the landless more clear. The rebellion of Enlightenment reason had nevertheless set the dialectic in motion, and now the Second Party System would be incited by a populist rebellion against elitist control. The secular American religion revolving around politics, with its parades and campaigns and conventions, was about to come into its own. The headstrong rebel destined to explode the aristocratic ruling class was the Battle of New Orleans hero General Andrew Jackson.

The 1824 presidential election was like no other in American history. With Monroe stepping down after his second term, four candidates competed in the general election, all from the same party. Andrew Jackson won a plurality of electoral votes, but not a majority. According to the Constitution, the race was then to be decided by the House of Representatives between the top three vote-getters. With the minimum votes necessary, the House, led by Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky, chose the second-place finisher, John Quincy Adams, son of John Adams (and thus our first nepo-president). Adams in turn made Clay his Secretary of State and thus essentially his successor, as the last four presidents all graduated from that position. Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson, a lawyer and war general from Tennessee, known as an indomitable ball of flaming red-hot thymos (I paraphrase) was incensed at the unseemliness of all this power-brokering. President Adams Jr.’s centralizing attempts at reform and infrastructure were equally despised as corrupt and “Federalist”. Jackson ran as a “Democrat” in 1828 — an election with vastly expanded voter laws than even the one before it — and won, becoming the seventh president of the country and the first who wasn’t a Harvard lawyer or a Virginian aristocrat. No, importantly to his base, he was a self-made frontiersman instead, a kind of American Napoleon. Henry Clay marshaled the conservative political forces opposed to Jackson’s populist uprising, thus creating the “Whigs”, and a new two-party system was born.

The tremendous force of Jackson’s populist opposition to elitism was such that his inauguration party in 1829 was as big a rebuff to Enlightenment reason as could possibly be imagined. The crowd celebrating at the White House behaved as an unruly mob, causing thousands of dollars in damage and scandalizing the old guard of Washington’s political elite. White House staff had to serve pails of liquor on the lawn to lure revelers out of the building. The hoi polloi had been symbolically linked with irrational passions of appetite and aggression, and so that is how they acted when imitating the rebellion they saw in their “betters”. But if the masses were corrupt, then certainly the elite were, too, even as the reason of a man captive to desire and anger is certainly corrupt as well. And thus Jackson’s populist actions against elitist control, like ending the national bank and fighting the power of corporations, were not without some relative value. Much less valuable, on the other hand, were populist actions like the Indian Removal Act, which constituted a plain rebellion against morality on behalf of the passions.

As for the Whigs, in my former treatise I characterized the polarization of Jacksonian Democrats and conservative Whigs as patterned after epithymia and thymos, respectively, and I hold to that. But along that axis there’s a cross-section of reason that complicates its dynamic. The populism driving the entire Second Party System was motivated by the appetites of the racist white men allowed to vote and all the corrosive thymic residue that entailed, reason being submitted to those passions. Whigs reacting to the immorality of such populism were driven to control the social vices they were observing, and exerted reason to that end. In all the unleashing of passions in this era, there also was occurring the Second Great Awakening whereby the Calvinist predestination of the previous century’s Great Awakening was giving way to free will activism and the proliferation of benevolent societies. Such attempts at moral reform found a home more easily on the conservative Whig side of the aisle, but in presidential politics it was definitely a weaker political force than the populist appetites for Manifest Destiny. Another interesting dimension of this era’s polarization is that the Democrats for all their opposition to federal power favored a strong president — strong, that is, relative to the legislative branch, all the better to exert the will of the people unencumbered by congressional deliberation. Whigs to the contrary favored a strong congress and a weak president so that reason and argument could hold in check the rashness of passion.

All that said, let us look then at an overview of the era:

Whigs won only two presidential elections, and each time their guy died early in office, Harrison after just a month and Taylor after sixteen. Harrison very well could have been a good president for the Whigs, but John Tyler, the vice president that succeeded him, was an abject disaster. He had switched parties from the Democrats and did nothing but conflict with fellow Whigs throughout his presidency. Still, the Whigs looked forward to the 1844 election when their main man Henry Clay had a good chance to win it all. But Tyler’s parting gift near the end of his term was to signal an interest in annexing the Republic of Texas. This gesture set off the heated populist desire for expansion westward (to which the Whigs were opposed, advocating internal improvement instead), and the election was thrown to Democrat James K. Polk, who gave full-throated support to Manifest Destiny. President Polk secured the Oregon Territory, such that the United States finally reached the Pacific, and then annexed Texas, picking a fight like a bully with our weaker southern neighbor Mexico, resulting, by the end of the Mexican–American War in 1848, in the annexation of California (just in time for the Gold Rush).

Whigs were repulsed by the injustice of the war and the avaricious land grab (House Representative Abraham Lincoln first made his name speaking out against it), but they also didn’t not participate in it. Several of the war generals enacting populist Democrat policy were in fact conservative Whigs, and so the party picked a prominent hero among them, Zachary Taylor, to run for president, if only just to win an election after such an impactful term in office by their opponent (Polk was not seeking a second term). Taylor was not a politician and struggled to function as one. In any case, traditional Whig economic policies like nationalistic tariffs and support for a federal bank were rendered obsolete by the Democratic-led expansion of the nation and economy. No great accomplishments can be attributed to Taylor or his successor Millard Fillmore of New York (a real politician at least) — unless you count the Compromise of 1850. Negotiated in congress by Henry Clay and Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, this collection of acts sought to organize the nation’s new territories and incorporate them into national politics while dissolving the issue of slavery. True to its name, both sides, for and against slavery, made concessions with the goal of peaceful coexistence. Texas would be accepted as a slave state, and California as a free state. Trading slaves in the District of Columbia would be outlawed, and fugitive slave laws in the free states would be strengthened.

The Compromise forecasted the end of the Second Party System as it just underlined how everything eventually had to realign around the issue of slavery. From the drafting of the Constitution and the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the issue of slavery was a can kicked down the road. But it could be so no longer. The Whig party wasn’t all abolitionists, though abolitionism certainly fit the reformist agenda of the Whigs better than the populism of the Democrats. There were proslavery Southern Whigs; there were proslavery Northern Whigs. This wasn’t going to last. In the 1852 presidential election, incumbent Millard Fillmore was rejected by his own party based on his signing of the Fugitive Slave Act. They went with another Mexican War general, whose name isn’t worth mentioning because he was a bad candidate and he lost. He lost to New Hampshire Democrat Franklin Pierce, a senator, brigadier general in the Mexican–American War, staunch anti-abolitionist, and, as it turned out, one of the worst presidents in U.S. history.

Two months after being elected, and two months before being inaugurated, Pierce was in a train wreck with his family. His only son, aged 11, was killed. He and his wife survived but entered the White House deeply depressed. He took the oath of office on a book of law rather than a Bible (as did John Quincy Adams at the beginning of this party system). Eventually Pierce signed into law a piece of legislation by his fellow Democrat Senator Stephen A. Douglas known as the Kansas–Nebraska Act. It effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by allowing the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to legalize slavery if they so chose. This, combined with his execution of the Fugitive Slave Act, caused his opponents, the Whig party, to splinter, and it never recovered. Kansas, meanwhile, was turned into a potential state upon which the balance of the whole nation swung. Violent men, for and against slavery, flooded into the territory to fight for their cause there, thus creating the phenomenon of “Bleeding Kansas”. It was a prelude to something much bigger. A new political entity formed from the debris of the Whigs, calling itself the Republican party and prioritizing the abolition of slavery. By the power of polarization, Pierce’s own Democratic party agenda thus became centered on the preservation of slavery as a lawful right in the United States of America. In destroying the Whigs, the Democrats were also destroying themselves.

Χ. The Third Party System (1856–1896)

Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Gilded Age

The Republican party first appeared in the chaotic 1854 midterm elections, in which it did well, given the crowded, multi-party field. By the 1856 presidential election, it formed the leading opposition to the Democrats. The Republican candidate, John C. Frémont of California, lost to James Buchanan, proslavery Democrat from Pennsylvania. Buchanan fought to protect slavery and to expand it in Kansas by means of a disputed commission that the territorial governor there called fraudulent, and this caused an intraparty rift between him and longtime rival (and presidential hopeful) Stephen A. Douglas. This rancor led to a divided Democratic ticket in 1860 that threw the election to Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. It’s funny how the Democrats of this era crashed on the rocks like this and sunk their ship. That their Whig opponents did so is entirely understandable given how the realignment around abolitionism worked. But why couldn’t the Democrats survive that transition? Hold the party together, defeat Lincoln, and we get a whole different history, right? But that’s not how party systems work. The demise of one magnetic pole spells the doom of the other one as well.

As it happened, Lincoln’s victory incited South Carolina to secede from the Union even before he took office, and other Southern states followed suit. Hence the lame duck James Buchanan was commander-in-chief when the Union sundered, and he did nothing to stop it. His every move only contributed to the crisis.

This then is the Third Party System, and it originates in polarization of the most destructive type imaginable. The fractality of the Civil War poles is so piercingly evident, it’s hard to tell which of North or South relates primarily to thymos or epithymia. The white voters of the South wanted to do what they wanted to do, suggesting epithymia, while the white voters of the North strove to control their behavior, suggesting thymos. Yet the South, repulsed by the North, were trying to break from it, suggesting thymos, while the North, attracted to the South, were not letting it go, suggesting epithymia. Polarization of the passions both tears apart and holds together at the same time. The presence of reason, meanwhile, can be easy to overlook amidst all the fraternal bloodshed. But the abolition of slavery — that is the reason, the emancipation of four million African Americans from bondage.

This is the Χ-section of the chiasmus portion of the octave, reserved for particularly Christ-like typology. A paschal descent into hell for the emancipation of slaves is particularly Christ-like typology. The war no doubt was reason transgressing reason, but I think if we squint we can see reason transcending reason, too. The year the fighting ended, the paschal full moon occurred on Tuesday, April 11. Hence when the North triumphed over the South at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, it was Palm Sunday. And then the Great Emancipator took a bullet in the back of the head on the sixth day, Good Friday, the 14th day of April, 1865. He died that Saturday morning, the 15th, the Great Sabbath. That Easter Sunday, he did not rise again. (Maybe because he spent Good Friday evening attending a play at a theater? Just a guess.)

But the country went on.

Vice President Andrew Johnson of Tennessee was an anti-secessionist War Democrat who joined Republican Abraham Lincoln for the latter’s reelection in 1864, on a “National Union” ticket. It was a strange thing then, after Lincoln’s assassination, to have a Southerner, who had right up to the Emancipation Proclamation owned slaves, be in charge of the country at the end of the war — a war that the North fought and won for the sake of freeing the slaves.

As harmful as this was for the nascent civil rights of black Americans (which Johnson did not prioritize, though others did, and some gains were made), it at least gave the subservient Democratic party a political identity going forward that was not secessionist and that accepted emancipation. Republicans will go on to dominate both this party system and the next, but they could hardly accomplish anything in this dialectically designed country without a loyal opposition. That’s the only positive thing I can think to say about this historical development, which was largely a disaster. Johnson’s ambitions to be reelected in 1868 saw him try and fail to be the Christ-like unifier that his predecessor was. He became the first president to be impeached by the House of Representatives and barely escaped conviction in the Senate by one vote. The National Union party proved quite temporary and the natural polarization of Republicans and Democrats was set in motion until now, notwithstanding a few realignments in the interval.

Meanwhile the beleaguered Reconstruction continued apace. Republican Ulysses S. Grant, the army general credited with winning the war for the North, won two terms in office as president, but the prospects of the second one were tanked with a financial crisis, the Panic of 1873, which would effectively end the concerted attempt at reforming the South. The results of the disputed, fraud-riddled election of 1876 were such that Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was allowed to be president at the cost of aborting the Reconstruction: all military occupation in the South was to end, as were all prohibitions against Democratic governments. The event neatly divides the Third Party System into three chapters, a pattern not uncommonly found within the Χ-section of larger structures. It’s the same threefold ascent that caps the octave structure like a weekend capping a work week. The Greek symbols I use to symbolize it are Ϛ–Ζ–Η (stigma–zeta–eta), the Greek numerals for 6, 7, and 8. In terms of days of the week, these conform to Friday, Saturday, and Sunday as understood in Christian symbolism: preparation, sabbath, and Lord’s day (which is how these days translate literally from Greek). In spiritual praxis, the pattern is expressed as purification, illumination, and perfection. Friday’s preparation, or purification, consists of a crucifixion absolving sin. Saturday’s sabbath, or illumination, consists of God resting in His creation. And Sunday’s resurrection signals the perfection of the Lord’s day, the eighth day, the day of a new creation.

As with the cosmic chiasmus, it is not abnormal for structures of this type to trace their pattern in mimicry without virtuously fulfilling their forms. That is largely what we have here, especially in the finale. The so-called Gilded Age that starts with Hayes is a picture of perfect travesty where real perfection ought to be.

To be sure, the notion of a “gilded age”, as opposed to a golden age, is an ironic and euphemistic expression, coined by Mark Twain and applied to this period by later historians. The implication of the moniker is that rather than being golden, there was a thin sheet of gold leaf placed over something that was very much not gold. American politics was at its most decadent at this time, with corruption, inequality, and injustice running rampant. Ever since the economic disaster of the Civil War, deflation was in effect, which benefits creditors and harms debtors. The rich kept getting richer, and the poor poorer, without any money even changing hands. The theme of the day was that politicians right and left persisted in not addressing this problem (for them to do so would take another economic crash and a political realignment; more on that later).

When Andrew Jackson invented populist democracy in America, moreover, an important change he made was kicking out all the career civil service members from their government jobs and replacing them with cronies who would be loyal to him. This was called the spoils system because, as the thinking went, to the victor go the spoils. In Jackson’s mind this was a cure for corruption since he saw the aristocratic elite as having an undemocratic stranglehold on how the country was run. With the spoils system, how the government would operate would depend more closely on who the voters elect.

But it’s certainly not hard for us now to imagine how easily corruptible, dysfunctional, and downright inefficient it can get when you staff the government according to popularity and loyalty instead of merit. Merit has a basis in rationality, whereas popularity and loyalty are easily usurped by the lower passions. Under the spoils system, whether one gets work or not depends on what you’re willing to do for those who are in power. Such loyalty may be an especially important virtue for the military, especially in times of war. How else would you get so many soldiers to fight to the death? But carry that mentality over into peace time, into the civil service, and you get a system of party bosses, funded by graft and productive of violence, who control all the offices of power very undemocratically — not unlike the aristocratic system Jackson originally rebelled against, except less accountable to reason and more moblike. This corruption took deep root during Grant’s presidency; he was a great war general, and as president was not without achievements, but he had a much spottier record in that office. The corruption spreading in his era hit its apogee in the Gilded Age. Tammany Hall in New York City, associated with the Democratic party, was the biggest, most famous political machine, but all the cities had them, as did both of the parties. National politics worked the same. The parties were indistinguishable from crime syndicates, and all anyone in power was fighting for anymore was spoils.

But who exactly was in power? The answer is less clear in this period than in others. Presidents often were in direct conflict with forces in congress and elsewhere that were more powerful than them, and party bosses themselves were enslaved to the system. Republican James A. Garfield of Ohio ran as a reformer and might have been a good president, but he was shot down by a deranged office-seeker looking for his cut of the spoils. Garfield served just half a year. His vice president Chester A. Arthur of New York had been in the pocket of one of the era’s most important bosses, Republican Senator Roscoe Conkling, also of New York, who from his seat in congress led the defense against reforming the spoils system. Arthur surprised people, though, by following through on a piece of Garfield’s reform legislation. By the next election, the intraparty battle that ensued threw the presidency to — for the first time since before the Civil War — a Democrat, Grover Cleveland, again from New York.

Cleveland was a so-called Bourbon Democrat, which meant that concerning business and currency policies he differed from Republicans not at all. He sure did believe in limiting the federal government’s involvement in people’s affairs, though, issuing vetoes in massive quantities, at a rate much higher than any other president, mostly to deny pensions to veterans or federal aid to farmers in dire straits. Such self-abnegation on the part of the government certainly limited corruption (veteran pensions had been abused), but at the expense of also not giving a hand to citizens in need. This was a time, see, of not only long-standing deflation but also government surplus. Deflation, besides making debts increasingly harder to pay off, encourages those with money not to spend it. The government was running a surplus year after year, and wasn’t spending it. Republican Benjamin Harrison of Indiana (who, as the grandson of William Henry Harrison, was our second nepo-president) presided over a Republican-controlled congress that turned that trend around and emptied the coffers, spending — for the first time — over a billion dollars. Political blowback to what was criticized as wasteful spending (a lot of it was corrupt) brought Cleveland back into power the next election. No incumbent president ever won an election in the Gilded Age.

Now, if you’ve read all that, I must apologize: it is all so stunningly uninspiring. This was a period of massive immigration of desperate peoples into the country, of horrendous working conditions and economic slavery, of the disenfranchisement of black people throughout the South, of the most terrible atrocities committed against Native Americans like at Wounded Knee, of singular industrializing tycoons like Carnegie, Morgan, and Rockefeller making all the money there was. And it all concluded with the Panic of 1893 precipitating the deepest, most excruciating depression the country had known to that point. The Civil War... it was supposed to be a purification. The Reconstruction was meant to be when the divine order of the world was set in place and allowed to shine. The Gilded Age was supposed to be a golden age of perfection. Those ideals feel so depressingly distant from the reality.

Gah, I didn’t even have any pretty maps in this chapter.

But it gets better, doesn't it?

Had the 18th century Americans achieved dispassion, would they have been ought to declare Independence?

Is the 4th of July a holiday in which we celebrate America’s communal θυμός via indulging our personal έπιθυμια?