The tradition of the Orthodox Church as I have been given to understand it, part 1

It's not transmitted through media or scholarship, however useful those might be

I’ve heard a Roman Catholic friend defend his tradition against accusations of theological variability by pointing to the Eastern Orthodox tradition as being no different. Citing an historical study of academic curricula at Orthodox theological schools, he claims that the hesychastic differentiation from Western tradition is a recent development subsequent to the ressourcement movement among his own churchmen, and not, as commonly claimed by Orthodox today, the result of a continuous tradition with the likes of St. Gregory Palamas (14th c.). He adheres to Thomism, broadly speaking, and thus believes theological tradition is something that can be gauged by what’s taught in the academies. He has assessed the Orthodox Church by Scholastic values and has found it doesn’t measure up; asking a Roman Catholic question, he receives a Roman Catholic answer.

I’d bet there’s a good academic response to this claim, but I’ll leave that for academics to write. I’m moved to speak from my own experience, to try, if I can, to explore what the tradition of the Orthodox Church consists of, if not scholarly knowledge.

Because it’s not like there aren’t a lot of books. There are indeed plenty of books. The wealth of literature in the Jewish tradition was integral to the early life of the Church from its very beginning. Books as we know them (codices, instead of scrolls) only exist because they were popularized by the Church. And as the Evangelist St. Matthew wrote in his book, “Every scribe which is instructed unto the kingdom of heaven is like unto a man that is an householder, which bringeth forth out of his treasure things new and old” (13:52). As old books were treasured, new ones were written. Down to today, the writings of Church Fathers are treated by the devout like holy relics — and new ones continue to be written.

But books continue to proliferate in the holy tradition of the Church only because, and precisely because, they themselves aren’t the source of the holiness. Biblical accounts of the early Church depict the Apostles reading books, preaching from them, using them (especially the Psalms) for their prayers and worship, certainly. But from these same sources we see that the identity of the Church comes from the triune God. All according to the good will of the Father, it comes from the Body of Christ as celebrated in the Eucharist, combined with the descent of the Holy Spirit, beginning at Pentecost and passed on to others by the laying on of hands. It is the image of a man: body formed from matter, animated by an inbreathing spirit. A body without a spirit would be a corpse, or a zombie. A spirit without a body would be a ghost. So you have the anaphora (“lifting up”) of Christ’s Body on the one hand, and the descent of the Spirit on the other.

My history with the Church begins in November of 1998, during my first semester of college. One Friday evening, I was invited by a friend from school to attend her Orthodox parish in the Allston neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. That Sunday morning I came. The Divine Liturgy that I witnessed, along with the love the Christians there had for each other, convinced me straightway that this is where I should aspire to be. That’s the quick story of how I came to be there. The story of how the parish came to be there is itself a much longer story. Rather than work backwards from 1998, I think I’ll choose a relevant moment from the past and work forward.

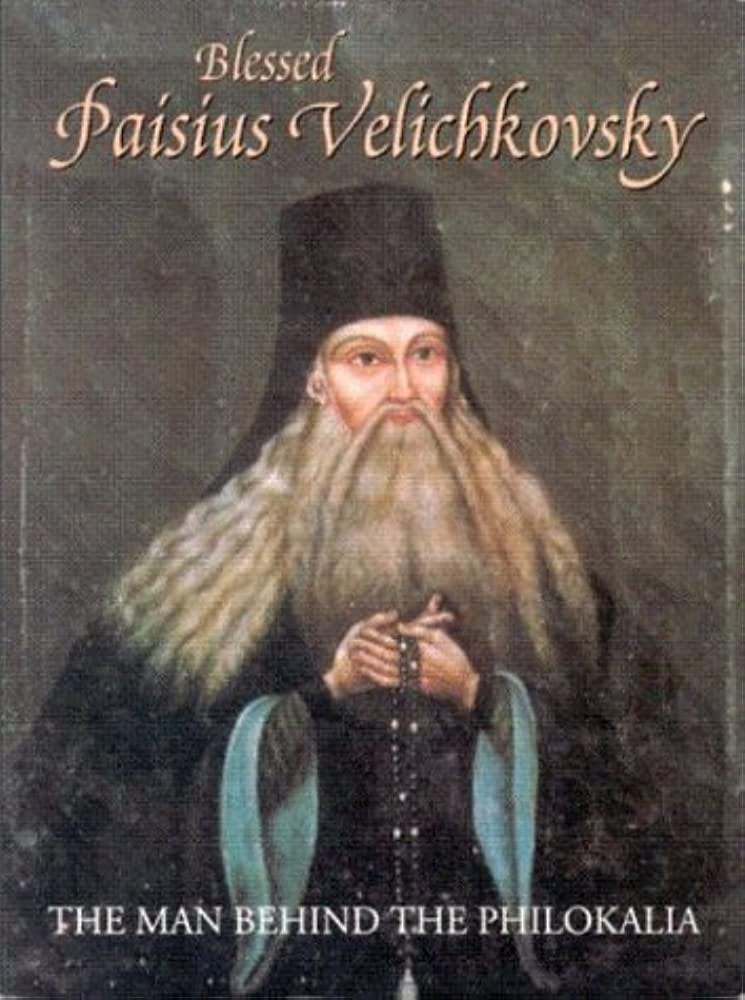

St. Paisius Velichkovsky lived in the eighteenth century (1722–1794), at a particular nadir of Church history. To describe to a contemporary audience where he was from and the various places he sojourned is very laborious because the identities of places and peoples he lived in and among have been much contorted and corrupted in the time since. Indeed the flux of identity in this region began long before our saint arrived on the scene.

What we can say is that his family was from the city of Poltava and at a young age he went to school in Kiev, beginning his monastic life near that city while still a teenager. His background was Orthodox, and it was Slavonic speaking. It would be anachronistic to call this region Ukraine. European nationalism wouldn’t begin to inflame the region until the nineteenth century, Ukraine not becoming a republic until the Soviet era in the twentieth century. No, this was not yet an age of nationalism but of empires, and St. Paisius’s country was caught between them.

From 1362 to 1667, what we now know as Ukraine had been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and later, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in heavy Roman Catholic influence in the region. Then the Tsardom of Russia won back its Kievan homeland, lost at first to Tatars several centuries before, but by the time St. Paisius was born in 1722, Tsar Peter the Great had transformed Russia into a westernized empire. For the Church this was devastating, as the Moscow Patriarchate and its independence from the state had been abolished, and the synod of bishops that replaced it was reduced to the status of a government ministry. Later in the century, during St. Paisius’s mature years, Empress Catherine the Great, to support her many territorial wars, would appropriate all Church property for the state, empty all the monasteries, and, according to Western Enlightenment principles, secularize public education, banning from it all religious content. Russia had been rendered spiritually desolate by its rulers.

By then, however, St. Paisius had left the boundaries of the Russian Empire. The Kievan region was bereft of advanced spiritual guides, so to find one he traveled south. The Turks of the Ottoman Empire had been ruling the Balkans with an iron fist for centuries by this time, so the Church suffered badly there also. However, in the lands then known as Moldavia and Wallachia (Vlachia to the Slavs) — where the language spoken was known as Moldavian or Romanian — things were different. (The northeastern half of Moldavia is now the Republic of Moldova; the southwestern half along with Wallachia is part of Romania.) These Romanian-speaking lands paid heavy taxes to the Ottomans but enjoyed a degree of autonomy not had elsewhere in that Empire. In this darkest of eras for the Church, the light kept shining in Romania. In the ecclesial tradition available to St. Paisius in Kiev, he learned enough to know the essential importance of ceaseless prayer and having a spiritual father. He at last found these in Vlachia where he met the holy Abbot Basil of Poiana Mărului, elder of the Buzău Mountains. St. Basil was a faithful transmitter of the hesychastic tradition from centuries past, a practitioner of the Jesus prayer, and a guide of souls to sanctity. St. Paisius made quick progress. In just a few years, out of fear of ordination and desire for stillness, he attained the blessing to travel to Mt. Athos, the legendary monastic peninsula in Thrace, Greece.

He was at first not so fortunate on Mt. Athos. The place was overrun by Turks, and the quality of spiritual life was not strong. Great patristic literary treasures lay in their midst, but hardly anybody knew that they existed, let alone how to make use of them. Not finding a teacher to live with, St. Paisius settled in as a hermit, practicing as best he could the example shown him by his Elder Basil — who visited the Holy Isle and there gave St. Paisius the full monastic tonsure (he had previously been only a riassophore monk, which does not entail taking full vows). With his elder’s blessing he made a life on Mt. Athos, engaged in hesychastic prayer and also laboring both to learn the ancient Greek language (modern Greek by this point had significantly changed) and to track down the spiritual writings he needed for nourishment. Many of the works he helped rediscover were not long after collected for publication as the epoch-defining Philokalia by Sts. Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain and Macarius of Corinth (in 1782). St. Paisius would spend his life translating these works into Slavonic.

But not only that. Remember, the source of tradition is persons, not books. On Mt. Athos, first one monk convinced the budding elder to let him live alongside him — not as a disciple, but as a co-struggler. More would come, a community would gather, half Slavonic-speaking and half Moldavian-speaking, and they would all be disciples of St. Paisius. In obedience to others and to God, he’d be made a priest-monk and an abbot. Outgrowing where they were, in 1763 the community moved to Moldavia where there was greater freedom from the Turks.

St. Paisius thrived in Moldavia, first at Dragomirna, then Sekoul, then Niamets. His spiritual fatherhood altered history, especially in nineteenth-century Russia, which benefited from his translations of philokalic writings into Slavonic, but most importantly from his disciples. After his death, government meddling scattered his spiritual children, diffusing them all throughout the spiritually parched Russian lands. St. Paisius wasn’t the only eighteenth-century luminary that fed into Russia’s nineteenth-century hesychastic revival (a full prostration to St. Tikhon of Zadonsk is due), yet through one disciple, a monk Theodore, who was elder to St. Leonid of Optina, can his legacy be traced directly to the famous line of Spirit-filled elders at Optina Monastery, fourteen of whom are canonized. Gifts of prayer, teaching, clairvoyance, humility, and love were passed from one spiritual father to the next, even as St. Paisius yearned for it to happen in his own life, and indeed as has happened throughout the apostolic Church from the beginning, yet here in great volume, visibly affecting the destiny of an empire — if only to justify its existence just a little bit longer.

It was St. Nektary of Optina who was the elder at the monastery when the Bolsheviks came to shut it down in 1923. The diaspora that occurred at this time will at last bring our story to America. In the early 1960s a bright Californian man in his twenties, formerly a Buddhist after being raised a Methodist, seeking for ancient truth found it in the Russian churches filled with exiles from the Soviet Union. He and a Russian friend formed a brotherhood dedicated to publishing Orthodox reading materials in English. Their spiritual father guiding them in their efforts was the Archbishop St. John Maximovitch of San Francisco. St. John was undoubtedly the brightest luminary there, a great wonderworker with gifts of prayer and clairvoyance and healing and teaching and sheer love. He is a new St. Martin of Tours for our times. But he was by far not the only bearer of holy tradition surrounding this young brotherhood of Eugene Rose (the Californian) and Gleb Podmoshensky (his Russian friend, a former seminarian). In fact there were many such apostolic links, more than can be recounted — disciples in the Paisian tradition, in the tradition of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, spiritual children of St. John of Kronstadt, and more close connections to New Martyrs killed by the Soviets than anyone could have hoped for.

When the holy Elder Nektary of Optina died in exile from the monastery in 1928, it was in the company of a disciple, Fr. Adrian Rymarenko. It was to Fr. Adrian that he entrusted the care of another, younger disciple, the future Bishop Nektary of Seattle. Bishop Nektary had been to Optina Monastery in its twilight and his family had Elder Nektary as their spiritual father for several years. Both Fr. Adrian (eventually Archbishop Andrew of Rockland, New York) and the future Bishop Nektary came to America and were among those to pass the Spirit-filled hesychastic tradition on to Eugene and Gleb, whose brotherhood was named after St. Herman of Alaska.1 After St. John Maximovitch’s repose in 1966, his vicar Bishop Nektary would be an especially close mentor to the younger men. He tonsured them as monastics in 1970 at their property in Platina where they would found the St. Herman of Alaska Monastery. He ordained them to the priesthood in 1976 and 1977. Gleb, now Fr. Herman, was to be the abbot, being the senior of the two (by a few months), a native Russian, a cradle Orthodox, and a seminary graduate. Eugene was tonsured as Fr. Seraphim.

Together their monastic and missionary labors flourished. But as often happens, these things don’t last as long as we think they should. Young St. Paisius Velichkovsky was with his elder St. Basil for just three years before being chased by heavenly desire to Mt. Athos. Fr. Seraphim Rose was the disciple of the holy Archbishop John Maximovitch for about the same amount of time before the latter’s repose in 1966. Then after twelve years as a monk, the last five as a priest-monk, Fr. Seraphim himself died from a blood clot in his intestines in 1982, merely 48 years old.

So… the Orthodox church I walked into in Boston? In 1998? This is where they begin to come into the story. In the 1980s there began in North America two parallel mass conversions to Orthodoxy. My church was part of one of them. But the Orthodox Church hitting the rocks of passionate American souls made for a messy, messy situation. Conversion can be a long, hard process, as has been true in my case assuredly.

But this is probably enough for one post. I’ll pick up this story in my next missive, and hopefully draw some more conclusions from the narrative. I’ll try not to take too long to post. Looking ahead, however, I am daunted by the challenge. The hagiographical tone I’ve adopted thus far is going to have to move over and make room for something else.

Read Part 2 here.

My aim is not to bog down this narrative with footnotes and hyperlinks — Substack stats show people hardly ever click on links anyways. But here I’ll make one exception because it’s kind of ridiculous that I’m telling this part of the story when there are much better sources. Here’s just one: firsthand stories of Matushka Maria Kotar (mother of fantasy author Dn. Nicholas Kotar) at orthochristian.com/141292.html.

I have been struck again and again by the many and varied connections to be found between various saints and their spiritual heirs and forefathers. These relationships extend through time and outside time, horizontally and vertically so to speak. The Sunday of Orthodoxy brought it home for me again, when all the children were processing with the icons, mostly of their patron saints. With all these connections no wonder we can proclaim with such confidence that "this is the faith which has established the universe"!

This reminded me of the biblical genealogies. It would be interesting to see a spiritual genealogies mapped out.