To end war and create peace, put on the whole armor of God

Epithymia and thymos transformed for good

So… three weeks ago I wrote about epithymia and thymos (a.k.a. desire and anger) as destructive forces of polarization ripping apart the human soul on microcosmic and macrocosmic levels. I focused on the patterns of these passions as we experience them personally, but with the aim of eventually revealing the pattern at work globally, specifically in regard to the war in Ukraine.

This involved speaking about whole nations as if characters in a drama, and so one commenter replied, “[I] always had trouble myself with anthropomorphizing nations by their political actions, but it is true in your sense that we all participate in the culture/what-have-you that brings them about.” This point about anthropomorphizing nations is a good one. In the context of Western thinking, such characterizations are often made with improper grounding. “The French be like this, while the English be like this,” and so on. Underlying such characterizations there is no understanding of how the one and the many actually relate with each other; such metaphors are easily seen as simplistic and false because obvious counterexamples to the generalizations are not accounted for. It all might make for the semblance of a witty observation, but not one that matches the lived experience of those being generalized, not in any meaningful way.

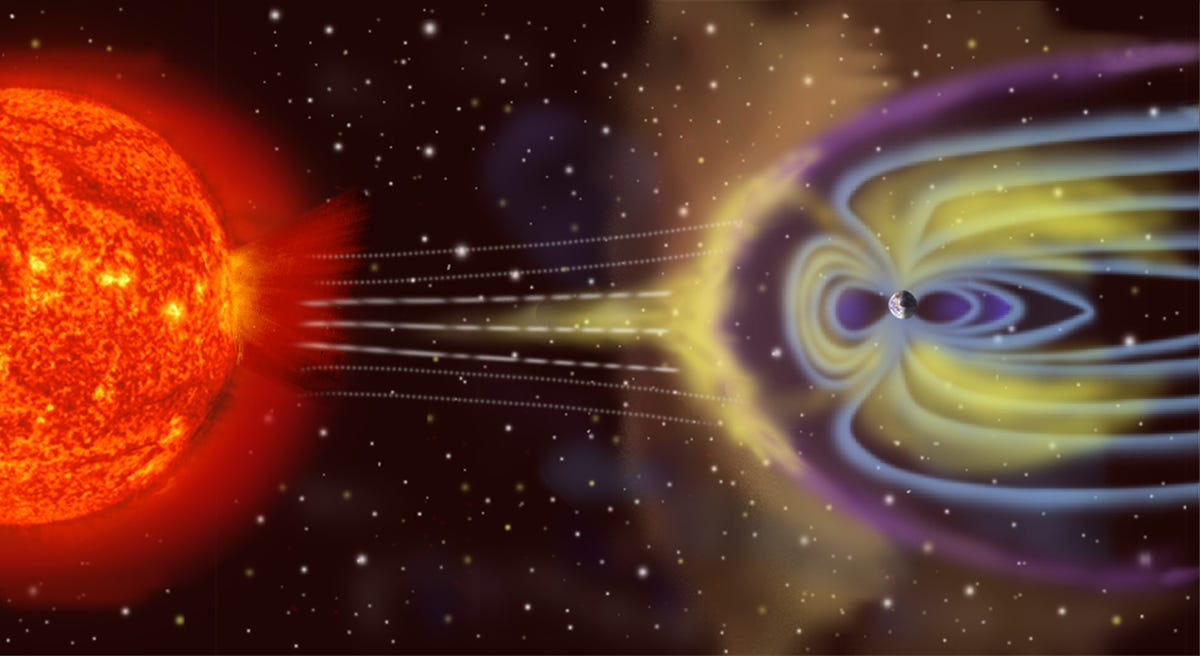

I think I’ve taken a different route to characterizing countries, as suggested by the commenter when he admits that we all contribute to the political actions of our national bodies. The difference is made in the fractal nature of the polarization I’ve been describing. It’s the nature of a magnet. A magnet is the way it is because of the collective action of its atomic constituents. A bar of metal like iron — the atoms of which all participate in the same magnetic field — itself will participate in that magnetic field and will interact magnetically with other magnetic fields. Likewise a nation of souls polarized by the passions will itself be polarized by the passions and will interact passionately with other polarized nations. It’s all a fractal: even if Russians submit to playing the thymic pole to the West’s epithymetic pole, that does not mean that the polarization of epithymia and thymos will not be found among Russian citizens themselves — even as all throughout one pole of a bar magnet you will find atoms that themselves are little dipole magnets. A Russian who wishes to diffuse the strife with the West, it then follows, cannot counter his nation’s vice-ridden thymos with vice-ridden epithymetic behavior. Russians exhibiting epithymetic passions, as well as Westerners exhibiting thymic passions, all participate in the polarization behind the violence. They’re still contributing to the pattern of behavior that causes all the problems.

That same commenter went on to say, “But I figure there’s also that best-versions-of-ourselves sense that we ought to cling to and not forsake even at the level of the nation, which isn’t necessarily political. The ‘true’ versions of the West and of Russia in that differentiated unity: the city of God living on as the city of man burns away?” Yes! The question remains how our national characters are to be redeemed amidst all the violence. The flip side of the bad news that we all contribute to national sins by our own sinfulness is the good news that we can each contribute to national virtue by our own commitment to virtuous living. As I’ve written about desire and anger in this journal, I’ve typically focused on their destructive aspects; sure enough, that is how we primarily know them. Only on occasion have I referenced their positive use, recognizing I would eventually have to focus on that, if merely to scratch the topic’s surface. Meanwhile another commenter reacted to that post three weeks ago, saying, “Powerful. Depressing, but powerful.” I swear it is not my aim to be depressing! Blessed are they that mourn, maybe, but certainly not out of self-pity!

So I set out to write a little on this excellent question, the same posed by St. Maximus at one point, “How will the soul fittingly bring about its beautiful conversion, using the passions — through which it had formerly committed errors — to give birth and subsistence to the virtues?”1

And St. Maximus is the best source to answer this question. I’ve reviewed some other sources — there’s fascinating history behind everything St. Maximus writes — but nowhere else is the presentation so fresh and lucid; I’ll concentrate this current study on his writings. I’m amassing relevant quotations from him on this topic and putting them in a Google Doc, if anyone wants to share in my research.2

To start, I’ll cut straight to the most powerful idea. In his highly relevant Four Hundred Texts on Love, St. Maximus writes,

Love of God is opposed to desire [epithymia], for it persuades the intellect to control itself with regard to sensual pleasures. Love for our neighbour is opposed to anger [thymos], for it makes us scorn fame and riches. These are the two pence which our Savior gave to the innkeeper (cf. Luke 10:35), so that he should take care of you. But do not be thoughtless and associate with robbers; otherwise you will be beaten again and left not merely unconscious but dead.3

The two great commandments, therefore, correspond to the shape of our soul; they’re specifically tailored to the predicament we find ourselves in. There’s plenty more to be said about the positive use of our epithymetic and thymic faculties other than just commenting on this passage, but… this is huge. It’s so comprehensive. Even if I only spoke about this one connection he draws, I’d never be able to exhaust it.

One’s approach to God should be a kind of love modeled after epithymia. It is a yearning, a longing for that which we lack; it is wanting. A submissive desire. When we desire created things, after all, it is merely a corruption of the kind of desire for God that is innate to our being. Here St. Maximus uses the Greek word agape for love; elsewhere in the context of describing the proper use of the epithymetic faculty, he’ll use the word eros. (In English eros is inseparable in meaning from carnal lust, but not so in Greek where it can have a philosophical meaning abstracted from fleshly desire.)

When we love our neighbor, on the other hand, there is an outward projection of the self toward the other that makes sense when both self and other are connatural. It would be presumptuous and hubristic to love God this way, but with one’s neighbor it is meet. One is to love one’s neighbor as oneself, the commandment goes. This outward projection conforms to the pattern of thymos, but you wouldn’t call it anger. It’s not about control. That’s how you’d characterize the thymic faculty when it is corrupted by material attachment and idolatry, but when it is restored to its original purpose, the movement is more about providing than controlling. When fatherly love is corrupted, for example, it controls and thrashes; when it is purified, it provides and protects, even unto self-sacrifice. Whereas the epithymetic love of God is a kind of feminine self-hollowing to make room for the other, the thymic love of neighbor is a kind of masculine self-emptying into the other.

I don’t know that the model of the magnet — so apropos as an illustration of the sinful passions — can be bent to describe this moral transformation and remain analytically coherent; I’d hesitate to illustrate it graphically in a way that wasn’t just totally symbolic. When we fully hollow ourselves epithymetically for God, He fills us with His love. It’s a self-emptying love, sure, in that the Uncreated God empties Himself into His creatures, and so our thymic love of neighbor conforms to the vectors of divine love we are filled with — but this is the love of the Holy Trinity we are talking about. The love between the three persons of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is both self-emptying and self-fulfilling. The distinction between in and out, upon which magnetic vectors are based, bears no meaning in a Godhead infinitely above all distinctions.

I’m describing the perfection of theosis here, when human love behaves like divine love, and so I’ve quite jumped ahead. Having heard the fullness of the promise, however, maybe now we’ll be more receptive to the process that gets us there. St. Maximus writes, “Almsgiving heals the soul’s incensive [thymic] power; fasting withers sensual desire [epithymia]; prayer purifies the intellect and prepares it for the contemplation of created beings. For the Lord has given us commandments which correspond to the powers of the soul.”4 We’re all in the first week of Lent now and, as Christians, should know this intuitively: while fasting is foregrounded in the purification of the soul because healing must begin with our epithymetic faculty, yet to it must be added almsgiving and prayer. I’ve heard many pastors through the years express the need to join almsgiving and prayer to fasting. It’s not because they’ve figured out the formula of the soul in their heads (like what I’m doing here); they’re just faithfully following the tradition of the Church formed around the practice of the commandments. It merely happens (not coincidentally) that fasting attends to our epithymetic ills, almsgiving (the Greek word for which has ‘mercy’ at its root) attends to our thymic ills, and prayer attends to our rational ills. These three practices do not themselves comprise all healing methods, but they do comprise the pattern that is comprehensive of all healing methods.

But let’s allow St. Maximus to get a little more granular on the topic:

Certain things stop the movement of the passions and do not allow them to grow; others subdue them and make them diminish. For instance, where desire [epithymia] is concerned, fasting, labor and vigils do not allow it to grow, while withdrawal, contemplation, prayer and intense longing [eros] for God subdue it and make it disappear. The same is true with regard to anger [thymos]. Forbearance, freedom from rancor, gentleness, for example, all arrest it and prevent it from growing, while love [agape], almsgiving, kindness and compassion make it diminish.5

This is where we see the distinction of eros and agape applying to our capacities for desire and anger, respectively. He says directly following,

When a man’s intellect is constantly with God, his desire [epithymia] grows beyond all measure into an intense longing [eros] for God and his incensiveness [thymos] is completely transformed into divine love [agape]. For by continual participation in the divine radiance, his intellect becomes totally filled with light; and when it has reintegrated its passible aspect, it redirects this aspect towards God, as we have said, filling it with an incomprehensible and intense longing [eros] for Him and with unceasing love [agape], thus drawing it entirely away from worldly things to the divine.6

I’ve arrived back at the fullness of theosis again. Fasting, almsgiving, and prayer have a way of shooting one directly to that destination. But I want to circle back again and focus on thymos, which is hard to define and understand. From the literature I get the sense it’s as if thymos and epithymia are responsible for naming each other. Thymos being directed outward and specializing in particulars (think left brain, as Iain McGilchrist describes it), is good at naming desire and giving us a sense of what it is. Epithymia, however (think right brain, per McGilchrist), pulls everything inward all at once and can only give us general impressions couched in an abundance of context as to what thymos is and how it should be understood. So let me add a few more vague impressions to help round out the picture.

I’ve characterized a virtuous thymos in terms of agape, of a sacrificial self-emptying outward into the other. It scorns fame and riches and prefers almsgiving instead. It provides rather than controls. All of this description preserves the outward vectors we associate with thymos, but the understanding of them is very lofty. In order to reach those heights, we need a stronger base in the neutral, practical sense of what thymos is. In praxis, the logos of the tripartite soul aspires (utilizing volition), while the epithymetic power desires (has appetite), and the thymic power strives (repelling obstacles). St. Maximus writes, interpreting the three days that people spent with Jesus in the wilderness before the multiplication of the loaves (see Matt. 15:32),

The three days, according to one mode of contemplation, are the three powers of the soul, by means of which they remain close to the divine principle [Logos] of virtue and knowledge: with the one [i.e., logos] they seek, with the other [epithymia] they yearn, and with the third [thymos] they strive — to receive incorruptible nourishment, enriching their intellect with the knowledge of created beings.7

This neutral aspect of a striving thymos is put to positive use specifically in the virtue of courage. Regarding Mosaic Law about foreign servants of either sex (see Lev. 25:44–46), St. Maximus starts to say, “The foreign manservant and the foreign maidservant are anger and desire [thymos and epithymia], which the contemplative intellect perpetually subjugates to the absolute rule of reason, so that they might, through courage [andreia] and temperance [sophrosyne], be of service in the life of virtue” — before again rocketing off to perfection:

They are not in any way granted their freedom until the law of nature is completely swallowed up by the law of the Spirit just as the death of the wretched flesh will be swallowed up by life everlasting, that is, not before the entire image of the unoriginate kingdom is clearly revealed, mimetically manifesting in itself the entire form of the archetype. Upon reaching this state, I say, the contemplative intellect grants anger and desire their freedom. It frees desire by transforming it into the unalloyed pleasure and undefiled bliss of divine love [eros]; it frees anger by transplanting it into a spiritual fervor, a fiery perpetual movement, and a right-minded madness [mania].

Clarifying what he means by mania, he cites St. Paul, “When describing himself to the Corinthians, he said: ‘If I am outside myself in ecstasy, it is for God, and if I am in my right mind, it is for you’ [2 Cor. 5:13], clearly calling the godly and right-minded madness [mania] ‘ecstasy,’ inasmuch as it places the right-minded and ecstatic intellect outside of beings.”8

The ecstatic intellect thymically strives to go outside of created beings specifically out of epithymetic eros for God alone. Thus the repulsive power of thymos finds its valiant use: “Whatever a man loves [agapa] he inevitably clings to, and in order not to lose it he rejects everything that keeps him from it. So he who loves [agapōn] God cultivates pure prayer, driving out every passion that keeps him from it.”9

Accordingly, the valiant, right-minded mania can also be translated as rage, and in the context of thymos, maybe it should be. Whereas before, the eros of epithymia was paired with agape for thymos, here we’re seeing another side of it. The feminine erotic desire is paired with masculine rage as extreme descriptions of an extreme freedom achieved in eschatological union with God. The freedom for the passions to behave this way is not unlocked until one’s worship is fully detached from created things and locked on God alone. To explain further, rage is to thymos what pleasure is to desire:

Desire that has been actualized, they say, is pleasure, when something good is actually present. Pleasure that has not been actualized is desire, when the actual good is in the future. Anger is the movement of premeditated rage [mania], and rage is an anger actualized. Thus, whoever subjects these powers to reason will find that his desire is changed into pleasure through the undefiled union of his soul by grace with the divine, and his anger changed into an undefiled ardor protecting his pleasure in the divine, as well as a right-minded rage consistent with the soul’s power of attraction for the divine, which makes it stand completely outside the realm of beings.

Thus as agape provides, mania protects, and between the two we have a fuller picture of how a purified thymos behaves. “But,” we are warned,

as long as the world lives within us, due to our soul’s voluntary attachment to material things, we must not grant freedom to these powers, lest they couple with the sensible realities that are kindred to them, and wage war on the soul and take hold of it, like a prisoner of war taken captive by the passions as in ancient times the Babylonians took Jerusalem.10

We must remember this same Father praising the virtue of rage also praises the virtues of humility and gentleness and does not contradict himself in doing so. “From courage and temperance,” he says regarding the virtues proper to thymos and epithymia, “the soul fashions gentleness [see Wis. 8:7, 4 Macc. 1:18], which is nothing other than the complete immobility of anger and desire in relation to what is contrary to nature, a state that some have called dispassion, and for this reason it signals the consummation of what can be practiced.”11 That which is dispassionate towards the ways of the world and the pleasures of the flesh, bearing nothing but kindness and gentleness and sacrifice for one’s neighbor — is simply a raging erotic mess for God. That’s just how it is.

I’ve tried to keep the discussion here grounded and practical, but each time St. Maximus keeps shooting us into the stratosphere of divinization. Every time I’ve tried to go lower, I think I’ve ended up higher. Let me at least, before I end this section and go on to the whole armor of God, finish with one of his favorite dyads in the Four Hundred Texts on Love, “love and self-control” — agape and egkrateia. (Egkrateia is translated as ‘temperance’ in the KJV.) He uses this formula several times in the work, but only in the fourth quarter does he explain where it comes from. “A soul’s motivation,” he writes, “is rightly ordered when its desiring [epithymetic] power is subordinated to self-control, when its incensive [thymic] power rejects hatred and cleaves to love [agape], and when its power of intelligence, through prayer and spiritual contemplation, advances towards God.”12 And again, right near the end: “Bridle your soul’s incensive [thymic] power with love [agape], quench its desiring [epithymetic] power with self-control, give wings to its intelligence with prayer, and the light of your intellect will never be darkened.”13

Ephesians 6:10–17

Finally, my brethren, be strong in the Lord, and in the power of His might.

Put on the whole armor of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil.

For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers,

against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.

Wherefore take unto you the whole armor of God,

that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand.

Stand therefore, (1) having your loins girt about with truth,

and (2) having on the breastplate of righteousness;

And (3) your feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace;

Withal, (4) taking the shield of faithfulness,

wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the wicked.

And (5) take the helmet of salvation,

and (6) the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.

The whole armor of God that the holy Apostle recommends contains (starting at v. 14) six pieces. St. Maximus comments on this passage in an early work of his, but I won’t refer to it here.14 In later works he would regularly pile different anagogical interpretations on top of each other, so there is nothing contradictory in my adding another one.

In the six pieces of armor, I see two pieces each for the three parts of the soul, there being in each case a negation of passion on one hand, and a positive virtue on the other.

For the epithymia, first of all we gird our loins, which is to say we abstain from pleasures, tempering our desires, restraining them for the sake of accomplishing something less ephemeral than pleasure — the truth. This is the negative epithymetic virtue, the self-control. The breastplate of righteousness, meanwhile, adorns the whole chest (the Greek for breastplate is thorax), not just the heart and reins that burn with innermost desire, but also the lungs which gape for the breath of life. And of course the object of desire is righteousness, as in that for which the blessed hunger and thirst. This is epithymetic virtue in its positive sense, as intense longing for the divine.

For the thymos, we first of all shod our feet with the preparation of the gospel of peace. An evangelion (‘gospel’) in historical context was an announcement of successful conquest sent out from the emperor to the masses. Feet, meanwhile, are the means by which the emperor’s men travel across territory and exert imperial control. But the evangelion with which the feet of Christians are to be readied is one of peace, the negation of anger. This image is of thymos that provides. The shield of faithfulness, however — indicating obedience to a God above all creation — is a kind of ecstasy, a right-minded madness that quenches all the fiery darts of the wicked. Here we have a positive image of a striving thymos, one that protects.

For the logos, we have the helmet of salvation covering the head of the soul. Salvation is something only necessary for the humble; the proud have no need of it. The humble gentleness that recognizes the need for salvation from above is a willing negation of reason’s head position in the world. Hence the helmet functions also like a veil. But “the sword of the Spirit, which is the word (rhema) of God” presents a positive image of a deified logos, discerning between truth and falsehood, right and wrong, with the inbreathed power of God, bestowing meaning on all creation by the divinely spoken word.

When you learn of the horrible violence in the world, something your own national body is contributing to by means of the polarization of the passions, know that you need to repent. Know that the polarization of your own passions is contributing mightily to the bloodshed you clearly see is wrong. When you repent, you’re going to have to learn how to redefine the pleasures you’re attracted to and the pains you’re repulsed by. You will need to learn how to take your desire and your anger, which have generated so much sin, have contributed so much charge to the magnetic field of corruption, and convert them instead into a kind of magnetosphere productive of and protective of life. You will need to put on the whole armor of God.

Ad Thalassium introduction 1.2.9. From St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios, td. by Fr. Maximos Constas (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2018), p. 80.

I also want to note Paul M. Blowers’s article covering this topic, “Gentiles of the Soul: Maximus the Confessor on the Substructure and Transformation of the Human Passions,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 4:1 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 57–85. I didn’t find cause to use it directly when writing this article, but I am fond of Blowers as a scholar and am greatly in his debt for his book Exegesis and Spiritual Pedagogy in Maximus the Confessor: An Investigation of the Quaestiones ad Thalassium.

Four Hundred Texts on Love 4.75. From The Philokalia, vol. II, td. by G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1981), p. 110. [PG 90.1065CD.]

Four Hundred Texts on Love 1.79, pp. 61–62. [PG 90.977C.]

Four Hundred Texts on Love 2.47, p. 73. [PG 90.1000C.] “Intense longing” is their translation of the single word eros.

Four Hundred Texts on Love 2.48, p. 73. [PG 90.1000CD.]

Ad Thalassium 39.2, p. 226. [PG 90.392B.] In the Greek here, “to receive incorruptible nourishment” is the objective of all three verbs pertaining to the three powers: the seeking, the yearning, and the striving. I’ve added an em-dash to the translation in attempt to reflect that.

Ad Thalassium 55.18, pp. 366–67. [PG 90.548C–549A.]

Four Hundred Texts on Love 2.7, p. 66. [PG 90.985BC.]

Ad Thalassium 55, scholion 25, pp. 382–83. [PG 90.568CD (where it is numbered scholion 33).]

Ambiguum 21. From Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, td. by Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014), vol. I, pp. 432–35. [PG 91.1249B]

Four Hundred Texts on Love 4.15, p. 102. [PG 90.1052A.]

Four Hundred Texts on Love 4.80, p. 110. [PG 90.1068C.]

Questions and Doubts 48. St. Maximos the Confessor’s ‘Questions and Doubts’: Translation and commentary, dissertation by Despina Denise Prassas (The Catholic University of America, 2003), pp. 145–47. This translation has since been properly published, but I only have the dissertation.

Interesting how different an effect simply flipping the cover image vertically has. (I promise I'm reading the articles and not just looking at the pictures!)

Looks like that one line that we who never read The Gulag Archipelago know from The Gulag Archipelago stands firm - "The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either, but right through every human heart." Thank you.