A little leaven leavens the whole lump

On the Pentecostal importance of leaven in the Eucharistic bread, and the centrality of azymes to the Great Schism — something of a follow-up to my article on Mid-Pentecost’s chiastic causality

I mentioned something briefly in my Mid-Pentecost article two years ago that I should like to expand upon now. The liturgical metaphysics explored there will be important background for these ideas here, so I recommend revisiting that piece if you’re so inclined.

The leavened loaves of Pentecost

In Leviticus chapter 23, the Prophet Moses relays to the people of Israel the Lord’s instructions on how they should keep the Feast of Weeks, or Shavuot, on the fiftieth day after Passover, once, that is, they enter into the Promised Land (“When ye be come into the land which I give unto you” — Lev. 23:10). Primarily, they are to make a wave-offering of two loaves of bread which are to be baked with leaven (23:17). Secondarily, ten animal offerings are to be burnt (seven lambs, a young bullock, and two rams; 23:18), but key is the wave offering of leavened bread. That is how to keep the Feast of Weeks in the Holy Land fifty days after Passover.

Christians best know this feast by its other name, Pentecost. For ancient Israel, Pentecost was one of the three annual feasts for which all adult males were to gather in Jerusalem (Ex. 23:14–17). It commemorates the giving of the Torah on Mt. Sinai, when they who had been miraculously freed from slavery in Egypt were consecrated with the blood of the covenant, that the Lord may be their God, and they His people. The exodus from Egypt at Passover was not an end unto itself, as if God were to say, “Okay, I freed you from Egypt; now... go do whatever makes you happy! Bye!” Symbolically speaking, Christ does not free us from death so that we can go off and live our best lives independent from Him, as if that were possible. No, Christ is Life Himself. He frees us from death so that we might be joined with life — and He is Life: we are freed from death to be joined with Him. This is the same reason He creates us in the first place: He frees us from non-existence that we might have His being. Likewise, as a typological event, the fiftieth-day covenant at Sinai, when Israel is joined to the Lord, is the purpose of the paschal exodus from Egypt. It occurs on the fiftieth day because that’s the ultra-eighth day, the brand new day succeeding a sabbath of sabbaths (7 × 7).

Yes, Israel is freed from Egypt in order eventually to inherit the Promised Land. Symbolically, though, that’s identical to the covenant on Sinai, just on a different fractal layer. They wander forty years in the desert, and symbolically, forty equals six (6 sabbaths = 42 ≈ 40). Periods of forty units, like a forty-day fast, are always in preparation for something, the way the sixth day is the preparation for the sabbath. The sabbath for Israel in this case, after wandering forty years in the desert, would be the conquest of the Holy Land, when divine energy rests within Israel’s mighty men in their triumph over the nephilim of the Philistines. Possessing the Land of Canaan, converting from nomads to farmers — after the manna has ceased and the first wheat crops have come in — that’s when Israel enjoys the new eighth-day beginning after the sabbath, in type. Consequently, the agricultural Feast of First-fruits, Bikkurim (see Lev. 23:9–14), coincides with Shavuot and sometimes the one name is used for the other (as at Ex. 23:16). Bikkurim’s fertile union of Israel with God in the Holy Land is already typified on the ultra-eighth–day Feast of Shavuot when Israel is wed to God by means of their mediator Moses, he who enters the tent guarded by the pillar of cloud (the Spirit), speaks to the Lord face-to-face (the Son), and sees the Lord’s back parts (the Father) from a cleft in the rock (the Son, by whom we know the Father). The Feast of Weeks’s fruitful union with the Triune God is already what possession of a harvest in the Promised Land typifies.

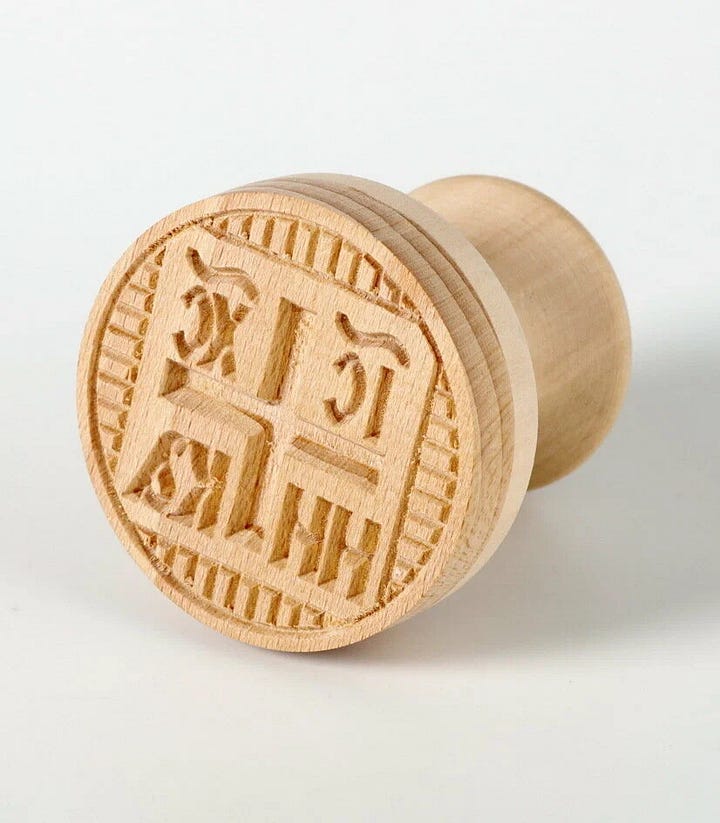

But even Moses’s experiences at Sinai are not yet the full reality in which all Israel’s types participate. The covenant forged on Sinai with the giving of the Torah, along with the annual Shavuot commemoration thereof, merely foreshadow the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Church at Pentecost, animating it as the Body of Christ, to the glory of God the Father — and it is not even the first historical event to do so. The Book of Jubilees (a jubilee = fifty, hence: the Book of Fifties), much favored in Second-Temple Judaism (including among the Apostles as evidenced in several places in the New Testament), depicts the Feast of Pentecost as a heavenly paradigm, one in which multiple historical events participate typologically. Most notably, Noah’s covenant with the Lord, made after the subsiding of the flood and the landing of the ark, was a fiftieth-day Pentecostal event (Jubilees 6:17), just like the covenant the Lord makes with Israel after the crossing of the Sea of Reeds. The idea of typos, recall, refers to a stamp. So Pentecost is like this eternal stamp that imprints itself cyclically throughout history, with varying degrees of clarity. The Book of Jubilees reckons the toppling of the Tower of Babel by a mighty gushing wind (10:26, a detail not found in Genesis), productive of a plurality of divided nations, to be a Jubilee-year (i.e., Pentecostal) event, if in a negative mode. Christians believe the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles at Jerusalem, in a mighty gushing wind and in cloven tongues of fire, redeeming the seventy nations with a mystical unity, is both an historical event on earth and that very eternal stamp sourcing all the other Pentecosts, the heavenly paradigm echoing cyclically throughout history. The wedding of God and man, the Uncreated and the created, is also a wedding of eternity and time. The eternal feast of Pentecost is planted firmly in the center of history like a bridegroom with his bride.

That’s the mystery the people of Israel were prepared by the Torah to receive. And in Leviticus 23 this mystery is expressed in the command to honor Shavuot in the Holy Land with offerings of bread baked with leaven. Leaven is the starter, the fermented, soupy dough used to spread life into other lumps of dough, and this detail that the Shavuot bread be leavened stands out as glaringly anachronistic in relation to the historical event being cyclically relived. At Passover, the Lord specifically commands Israel not to bring any leaven with them out of Egypt. It is strictly forbidden. Then, as soon as they cross the Sea of Reeds and celebrate the demise of Pharaoh, they go on a daily diet of manna from heaven (Ex. 16), which is milled and baked in pans as cakes that taste like sweet wafers (Num. 11:8 LXX). Fifty days after Passover, Israel at Mt. Sinai had no leaven or wheat to speak of.

Obviously (or at least it should be obvious), the use of leavened bread for the ritual of Shavuot in the Holy Land points to a mystery beyond the historical. It’s symbolic, and no less symbolic than when leaven was proscribed upon the exodus from Egypt in the first place (Ahmad 13–16). Leaven, with its yeast, is life. It is living, it breathes, it breeds. Any baker will tell you, it takes effort to keep leaven alive, to keep it from spoiling or starving. At Passover, the instruction was communicated to Israel, via the banning of leaven, that they need to leave the life of this world behind them. The life they knew in Egypt had to be entirely forsaken. No leaven was to be taken out of Egypt, yes, but they weren’t called out of Egypt just so that they could die in the wilderness (as they often feared, faithlessly). No, the Lord was to imbue them with His own life. Ultimately, this life is the breath of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, but first it has to be foreshadowed by the Law. So Israel participates typologically in the wind and fire of Pentecost via the giving of the Law and the blood of the covenant. And this is what is being communicated to Israel via the leavened loaves used as a wave offering in their annual commemoration of Shavuot. After putting away their old leaven every year at Passover, and observing the Week of Unleavened Bread, the children of Israel could begin to cultivate new batches of leaven, which would take a few weeks. By Shavuot their new leaven should be perfect. Their old life is taken away — for the purpose of a new life being given in return. Through death, they are resurrected. And the new life they are given is, via the types they are given to participate in, divine and eternal.

The eternal unity of Pascha and Pentecost

Christ’s Pascha is already Pentecost. Day one of the Feast and the ultra-eighth day after it are contained within each other. As the chiastic feast of Mid-Pentecost halfway between them shows, the two feasts are shining lights coming from a single source, spectrally spread through time across a fifty-day span. The liturgical unity precipitates from a theological unity: though they differ in their mode of existence caused by the Father, the Holy Spirit who proceeds is always-already present with Christ the Only-Begotten since the three Persons of the Holy Trinity are one in essence from before all eternity. Already at the Annunciation, Christ’s Incarnation is achieved specifically through the Pentecost-like descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Theotokos (Luke 1:35).

The Holy Spirit is present essentially with Christ, but He is made energetically present with the Apostles, who are to comprise His Body, in what St. Gregory the Theologian identifies (in Oration 41.11) as a gradual threefold process culminating in the perfection of Pentecost:

And next [the Holy Spirit wrought] in the Disciples of Christ (for I omit to mention Christ Himself, in Whom He dwelt, not as energizing, but as accompanying His Equal), and that in three ways, as they were able to receive Him, and on three occasions; before Christ was glorified by the Passion, and after He was glorified by the Resurrection; and after His Ascension, or Restoration, or whatever we ought to call it, to Heaven. Now the first of these manifests Him — the healing of the sick and casting out of evil spirits, which could not be apart from the Spirit; and so does that breathing upon them after the Resurrection, which was clearly a divine inspiration; and so too the present distribution of the fiery tongues, which we are now commemorating. But the first manifested Him indistinctly, the second more expressly, this present one more perfectly, since He is no longer present only in energy, but as we may say, substantially [οὐσιωδῶς], associating with us, and dwelling in us. (NPNF 2.7, p. 383; PG 36:444AC)

Through a triadic process patterned after Tabernacle worship, which is to say, akin to purification, illumination, and perfection, we are raised to the measure of Christ. But at Christ’s Pascha, as when Christ breathes on the disciples in the locked room, saying, “Receive ye the Holy Spirit” (John 20:22), Pentecostal perfection is already fractally present. It was already present during His three years of ministry; it was already present at His Incarnation; it was already present when He shared His Body and Blood with the disciples at the Mystical Supper, instituting the mystery of communion. Every time we the Church celebrate the Divine Liturgy as commanded, we, as ones who have attained the true Promised Land, participate in the perfect communion of God, which includes the complete paradigmatic journey from Pascha to Pentecost, from the leaving behind of the corrupt life of this world to the imbuing with the life of the Spirit. How else could we become the incarnate Body of Christ, if not through the descent of the Holy Spirit?

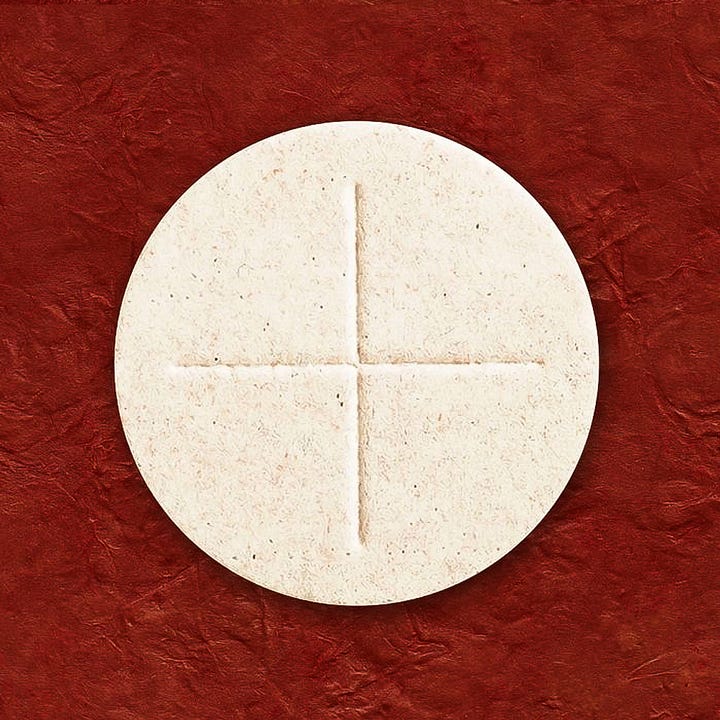

Hence, as a matter of unquestioned apostolic tradition, for the Church’s first eight centuries, without variation, using leavened bread for the Eucharist, like the wave offerings of Shavuot, was the universal custom. This fact is not disputed. There was one early Ebionite sect from the ante-Nicene period which included the use of an unleavened pascha bread among a litany of other Judaizing practices, but this sect was roundly anathematized from the Church, and written against by many Church fathers. In the seventh century, the Armenians, long cut off from the Church since their rejection of the Fourth Ecumenical Council in the fifth century, began to adopt a series of liturgical reforms including the cooking of meats in the altar for priests and using unleavened bread for their communion. Such practices were noted and forbidden by the Quinisext Council of 692. All was well and good in this regard within the canonical, apostolic Church.

Advent of the azymes and the Great Schism

But then in the ninth and tenth centuries, the innovation of using unleavened bread for the communion host began to be instituted among the Franks in the Carolingian dynasty. The rise of this practice was contemporaneous with the Frankish addition of the Filioque to the Symbol of Faith. As the Eastern Empire was celebrating the Triumph of Orthodoxy, the Western Empire was initiating the triumph of heterodoxy. Both these Frankish innovations met with long bouts of resistance from the Church at Rome, until, that is, the eleventh century, in the run-up to the Great Schism.

When you zoom out and look at the schism between the Latin and Eastern churches as a broad historical movement, it appears that the insertion of the Filioque into the Creed is the central issue among the constellation of disputes between the two sides. You take a broad perspective, you get a broad impression: the matter is theological, doctrinal; it’s about the Most Holy Trinity. From the time of St. Photios of Constantinople in the ninth century to the Council of Florence in the fifteenth century, the Filioque (along with how its addition to the Creed disregards conciliar authority) is foremost on people’s minds. But if you look specifically at the rift that occurred in 1054 between the Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Cerularius and a band of papal legates sent to him by a since deceased Pope of Rome, the issue at stake consuming by far the most attention is the Latin innovation of using azymes, unleavened bread, for the Eucharist.

This is why the 1054 spat occupies the central position in the historical perception of the Great Schism that it does. It fulfills a symbolical need. For, in contrast to zooming out and taking a wide perspective, when you zoom in tight on the phenomenon of the Great Schism, down to a specific moment in time, you should expect to find incarnated there a quarrel over the most material aspect of Christian practice, an issue which, no matter how low it sits in the cosmological hierarchy, yet reflects the greatest and loftiest truths of Christian belief. This is why the sad affair of 1054 appears historically as a turning point, a hinge, despite the causes and effects of the Schism being spread out broadly on either side of it. In the year 1009, for example, over the issue of the Filioque, the Patriarch of Constantinople declines to include the new Pope’s name in the diptychs tracking which churches his church is in communion with. It’s not a wholly determinative action, just mere paperwork, but it’s still pretty significant, as not since then has there been a Roman prelate’s name in the diptychs at Constantinople (Runciman 32–33). That could be the date we all associate with the Great Schism — but no. For one thing, it doesn’t feature a moment of mutual excommunication (even if only among a very limited number of individuals), but crucially it doesn’t focus on something like the azyme controversy. This is when the idea of the Great Schism becomes incarnate in history, in 1054, with regard to the nature of communion bread.

It’s funny: modern commentators when describing the schism of 1054 are wont to say that things like the Filioque were too abstract and elitist to garner the attention of the populace, whereas the texture and flavor of bread was something everyone understood. But that hardly explains all the other moments in history when the Filioque occupied people’s minds over and above azymes. So why are we talking about 1054? Historians have wondered at how the supposedly pivotal event of the Schism was over something so apparently trivial, failing to see that it’s precisely because the symbolism of the holy bread embodies the trivial, raising it to a level of theological profundity, like Christ Himself in the Incarnation, that it sticks out to the historical perception, over and above other historical moments, as so pivotal.

The historians’ impression that the issue of azymes is theologically trivial stems from the Latin position that either way of presenting bread for the Eucharist is valid. They never, for the most part, advocated against using leavened bread, knowing full well that was the traditional practice. They only ever sought recognition that their innovation was a valid practice. Oh, among themselves, in the Latin West (pressed by the violence of Normans in developments that led directly to 1054), they prohibited the use of a leavened host, but that was because it was illicit, not invalid. They would not allow for it, and the reason was so that they would all conform to the same practice, as an expression of the unity of the Church.... Yet they themselves were insisting on deviating from the practice common to everywhere else, past and present. And why not? Why shouldn’t local churches have their own practices, according to their own sensibilities, even regarding the bread used for communion?

The Latins liked their unleavened wafers because it differentiated the material of the sacrament from the bread that was commonly eaten among the people. This appealed to their clerical sensibilities, despite that early patristic sources typically refer to the Eucharist as “common bread” (Siecienski 109f). In traditional churches, prosphora loaves can be, and commonly are, baked by lay people. Among the Latins (at the time), only the clergy would prepare the unleavened communion wafers. Cardinal Humbert, the hot-headed papal legate who initiated the Schism of 1054, expressed the Latin preference for unleavened wafers by saying how repulsive it was to receive for use as the holy bread something that could have been handled with the filthy hands of a common person, or even something that had been bought at market (Siecienski 125). And an important feature of the unleavened wafers is that they did not leave crumbs the way common risen bread does, which made the sanctity of the wafers easier to control. This was even more the case if they baked small wafers for the people instead of whole loaves, which they did. It was very important for the priests to control the sanctity.

The origin story of how the risen communion bread became wafers among the Franks is actually quite telling (see Graziano). This is a story that proliferated among the Latins themselves and is indicative of their piety. There was a monk named Wandregisel in the seventh century. He was nephew to Pepin, founder of the Pippinid mayoral dynasty from which rose the Carolingians, and had been courtier to King Dagobert, the last Merovingian to hold any real power before the mayors took over. But he spurned the life of the world and became a monastic disciple of St. Ursicinus, Irish hermit of the Jura Mountains, who had been the disciple of Irish missionary-monk St. Columbanus of Luxeuil and followed his rule. The Irish were known for their strict asceticism, and surely this held great appeal for Wandregisel as well. At one point in his life, he was living at a monastery during Advent and was charged with baking the communion loaves for Christmas. All Advent, however, he had pledged to endure the season’s cold (which was extreme that year) without ever warming his body by a fire. How was he going to bake all those loaves without feeling any heat from the oven? If he felt any such warmth, his fortress of ascetic control would be breached, his pledge would be broken, he’d succumb to the wiles of bodily pleasure and sin. He had a streak going — he can’t break his streak! What’s the solution? Learning like Paul to remain steadfast in faith both in times of want and in times of abundance (cf. Phil. 4:11–13)? Relying on the grace of obedience and prayer and the protection of God, instead of the strength of his will to maintain a streak of asceticism? No, none of that: the solution is technological. Using blacksmith’s tools, he devised long iron tongs with plates on the end to handle the loaves from a far enough distance. He managed to bake all the prosphora loaves for the monastery without ever giving heat to his body in that deep winter cold. A side effect of the process, however, was that each of the loaves had the life smashed out of it by the force of the tongs. Out between the two plates came wafers instead of risen bread. The results were liked, however. Without any life in them, the wafers conveniently lasted longer and were more easily stored. It became a local custom.

If this is the true origin of the communion wafers in the West, it took a long time for them to catch on. Wandregisel died in 668. The earliest historical reference we have to the practice is in 798, when Alcuin of York, a chief minister to Charlemagne and principal mind behind the Carolingian Renaissance, wrote approvingly of using unleavened wafers, likening them to Jewish matzah used at Passover (Louth 314; Graziano). It took even longer for the use of azymes to be instituted as common practice, which among the Franks happened at some point in the ninth or tenth century. It was not an issue that ever came up, for example, during the West’s schism with St. Photios of Constantinople in the 860s (Siecienski 113).

Regardless of the Wandregisel legend’s factual veracity, and regardless that presumably leaven was still being added to the dough before it was flattened to death, it is very meaningful that this is the story that was told, in the context of using unleavened wafers for communion bread, as the origin and justification of the practice. One’s own strength of will in asceticism in this instance is given preference over the grace of God and the tradition of the Church. Lacking trust that he could control his passions by means of obedience to anyone but himself, the figure in this story is willing instead to crush the life out of the communion loaves. This piety is presented as laudable, but according to the traditional philokalic spirituality of the Church, the virtue of obedience is to be prized far above efforts of asceticism. Asceticism, as essential as it is to the spiritual life (faith without works is dead), loses its purpose otherwise (works without faith too are dead). This legend literally depicts a tradition of man replacing what amounts to a commandment of God (cf. Mark 7:8), and all for the sake of works — the Protestant Reformation might as well have happened right there in Wandregisel’s kitchen.

Theology spelled out in grains of sacrament

Nevertheless, this origin story plays no role in the polemics of the azymes controversy. I shan’t rehearse here all the points made on either side of the issue, but suffice to say, the Latin defense of their practice included something of a symbolic argument, but relied most heavily on an historical argument. The relationship of these two aspects of their defense, symbolical and historical, says as much about their departure from orthodoxy as their use of unleavened bread.

For starters, they held that leaven symbolizes corruption, which it plainly does at many places in Scripture. Ignoring the wave offerings of Shavuot, we read in Leviticus chapter 2 that whenever grains were used for burnt offerings, they were to be unleavened (this rule pertained only to burnt offerings). This symbolized that they were not to be corrupted by sin. At Galatians 5:9 and 1 Corinthians 5:6, St. Paul uses leaven as a metaphor to explain that a little bit of false practice, such as unlawful fornication or insisting on circumcision for Gentile converts to Christ, spreads to the whole of one’s religion and spoils it. It doesn’t help that the Vulgate mistranslates these verses; instead of “A little leaven leavens the whole lump,” the Latin says, “A little leaven corrupts the whole lump.” Blessed Jerome himself spoke out against this mistranslation, but to no avail (Siecienski 83). As it happened, this word choice itself operated as spoiled leaven, corrupting the Latin mind to think of leaven predominantly as a symbol of corruption, despite being fully aware of many places in Scripture where leaven positively expresses the giving of life: “The kingdom of heaven is like unto leaven,” the Lord tells us, “which a woman took, and hid in three measures of meal, till the whole was leavened” (Matt. 13:33). (The three measures of meal correspond to the three workings of the Holy Spirit delineated by St. Gregory above.) But then, so what if leaven can be spoiled or good, symbolic of either corruption or life? That just means that we can use either bread or unleavened wafers for the Eucharist, right?

In either case, leaven symbolizes — which means it indicates, it embodies meaning, it means, no less so than words do — a kind of life, an animating soul, which either is mixed with death and works corruption or comes from God and abounds to life eternal. Symbolically, then, unleavened wafers are lifeless matter. That can be a good thing in context, if the life withheld from your burnt offerings is the corrupt life of this world. But it would be a bad thing if the loaves offered at Shavuot were without the life of the Spirit of God — imagine Judeans offering unleavened cakes at Pentecost! The impiety! The ingratitude and rebellion! It just isn’t done! The argument of Orthodox polemicists against the use of azymes for communion, based in this biblical language, and prompted by their experience with the heretical Armenians, has consistently been to see the bread as analogical to the human nature of Christ. Human nature consists of dust of the ground and the breath of life (Gen. 2:7), and Christ’s human nature is complete; it is body ensouled and soul embodied. A wafer unleavened is a soulless body, a zombie sacrament. Theologically, so the argument goes (cf. Louth 312–13; Erickson 137; Siecienski 127; Smith 166–67), this represents an example of either Apollinarianism or Eutychianism, depending on what fractal level you take the analogy to. The two natures of material body and animating soul have to be present in the humanity of Christ (contra Apollinarianism, which says Christ doesn’t have a human mind, only a divine mind) in order for Him to be connatural with us, for one thing, but also in order to express the fractal pattern of the two natures of Christ, human and divine, one nature that is deified and one that deifies (contra Eutychianism, which insists Christ has only one nature, disabling deification by confusing deified and deifier). The patterns of such heresies are barred from the Church because terrible spiritual consequences precipitate from them, and no less so when they are spelled out in grains of sacrament than when they are spelled out in words of doctrine.

On this second level of theological analogy, for instance, it would appear the Latins have removed the divinity from Christ — or in other words, in their use of azymes, they’re presenting the Body of Christ without the Spirit of Christ. The mindless Cardinal Humbert in fact claimed exactly that in 1054: he retorted to Orthodox theological criticism by trying a little theology of his own. This man had the temerity to proclaim, forcefully, that when Christ died, the Holy Spirit was not present in His Body, that otherwise He would not have died (Sveshnikov 11–12). It’s a teaching consistent with the use of azymes, but theologically it is unspeakably blasphemous, the busy intersection of an untold number of condemnable heresies. For starters it inexcusably contradicts the Chalcedonian definition of Christ’s two natures being inseparable (Sveshnikov 18). In other words, His natural human body cannot be separated from His divine nature, worshiped and glorified in three Persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And it doesn’t even make sense from the perspective of someone who upholds the Filioque (and Humbert absurdly blamed the patriarchate of Constantinople for removing the phrase from the, ahem, Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed [Runciman 48]). If you believe the Spirit proceeds before all ages from the Son, how could the Spirit possibly be separated from Its pre-eternal source (Sveshnikov 22)? You’d have to say the Body of Christ becomes no longer the Son, but then... what in the world are you communing with? Death? Truly, the use of azymes conforms to this Spirit-less anti-Pentecost, not that any subsequent defenders of the practice would be so bold as to put it in those words. Rather, they would (along with what Humbert says elsewhere [Erickson 139; Sveshnikov 12, 18–19]) deny that the consecrated azymes symbolize a human nature consubstantial with us, merely a divine nature supersubstantial to us — a dialectically negative image of the same teaching, but a closer depiction of Eutychian monophysitism. And it conforms to the doctrine of the Filioque, too, in that the Filioque depersonalizes the Holy Spirit, sidelining Him along with the leaven. It’s all of a piece, the spiritual doctrine and the material practice, like two natures of one hypostatic apostasy.

But again, to get back to the theological analogy put forward by the Orthodox, on a simpler human level, the leaven breathing and breeding in the bread dough symbolizes the soul animating the body of Christ’s human nature, consubstantial with us. And on a hermeneutical level, furthermore, a symbolic understanding of word and practice should also be operating as such a soul, bringing heavenly meaning to the letter of our Scriptures and the material of our sacraments. But the Latins preferred an historical argument for the use of azymes in place of bread. At the Mystical Supper on Thursday evening in Passion Week, so they maintained, Jesus was celebrating the Passover meal, and thus when He instituted the sacrament of communion, He would have been using unleavened matzah. This their most vociferous defense (before any theological justifications) comprises an historical claim verifiable by no human means imaginable, and there has never been any consensus about it, neither among Church fathers nor among scholars.

Apart from Christ dying on Friday afternoon and resurrecting very early Sunday morning, the chronology of Holy Week is impossible to nail down. A day consists of evening and morning, in that order, according to Genesis 1:5. So in the Judean liturgical mind, carried over into traditional Christian practice, days switch over in the evening. The fifteenth of Nisan, on the Hebrew lunar calendar, marks the first full moon of the spring, and therefore of the year, according to the Torah. Liturgically, this day kicks off a Week of Unleavened Bread in commemoration of the exodus from Egypt. The feast of Passover (Pesach, Pascha), when the lamb is slaughtered and it and the matzah are eaten standing up, quickly, with loins girded, shoes on, and staff in hand, is associated Scripturally with the fourteenth of Nisan, when it is prepared, but the meal doesn’t actually occur until the very end of the day. It’s a threshold event immediately abutting the evening of the full moon which opens the fifteenth of Nisan and the First Day of Unleavened Bread. But as much as I may speak clearly by using the terms Passover and First Day of Unleavened Bread to refer respectively to the fourteenth and fifteenth of Nisan, in fact our sources are not so precise with the labels. The terms as commonly used were interchangeable with each other. Paschal offerings are made daily throughout the Week of Unleavened Bread, after all, and unleavened bread is eaten already at Passover. With Passover operating as a threshold event, really we’re talking about one thing here. The duration of the Week of Unleavened Bread is like the space of a walled courtyard, and Passover is the gate. As Exodus describes it, the week begins “on the fourteenth day of the month at even,” and goes “until the one and twentieth day of the month at even” (Ex. 12:18).

Thus, when the Gospel according to St. Matthew says, “Now the first [day] of unleavened bread the disciples came to Jesus, saying, ‘Where wilt thou that we make ready for thee to eat the passover?’” (Matt. 26:17), this phrase is much more ambiguous than it appears at first. First of all, there’s no preposition there, as some translations have it, “Now on the first day...”; there’s no “on” there. Instead the word “first” is in the dative case, which indeed is a normal way to say a temporal phrase that in English would be translated with a preposition “on” — but not necessarily so. And the descriptor “of unleavened bread” does not specify if it means the fourteenth or fifteenth of Nisan. And because “evening and morning were day one” and the Paschal meal was held at the end of the day, at evening, we could be a day or more out from the appointed time for Passover, accounting for the approximate way that people normally speak. St. John Chrysostom puts it this way (in his Homilies on Matthew 81):

By “the first [day] of unleavened bread,” he means the day before that feast; for they are accustomed always to reckon the day from the evening, and he makes mention of this in which in the evening the passover must be killed (John 13:1); for on the fifth day of the week they came unto Him. And this one calls the day before the feast of unleavened bread, speaking of the time when they came to Him, and another saith on this wise, “Then came the day of unleavened bread, when the passover must be killed” (Luke 22:7); by the word “came,” meaning this, it was nigh, it was at the doors, making mention plainly of that evening. For they began with the evening, wherefore also each adds, when the passover was killed. (NPNF 1.10, p. 485; PG 58:729–30)

The ambiguity of the Synoptic accounts in one way is cleared up by the Evangelist John, he who was a central eyewitness to the events at hand and who wrote his Gospel last in part to fill in gaps of public understanding. He unambiguously depicts Holy Friday as the fourteenth of Nisan, Holy Saturday as the fifteenth of Nisan. Thus Christ’s crucifixion and death Friday afternoon occur at the same time the Passover meal is to be prepared and eaten and the lamb’s blood on the door frame protects the lives of Israel’s firstborn sons. As for the Mystical Supper, St. John doesn’t actually depict it at all, just the washing of the disciples’ feet afterwards, despite how elsewhere in the Gospel he goes so hard on the Eucharistic theme, illuminating the theology of it more clearly than anywhere else in Scripture. Only in the Gospel according to St. John does Christ say that He is “the Bread of life” (John 6:35, 48), that His flesh is living bread and His blood is drink, and that unless we eat and drink it we have no life in us, that just as He lives by the Father (i.e., consubstantially), so the one who eats His flesh will live by Him (6:51–57). The theological emphasis of the whole Gospel regarding the identity of the communion bread is thus made clear by this evangelist: Christ on the Cross is the Passover, and He is “living bread.”

But don’t be fooled by my polemic: none of what I’ve said can actually debunk the historical claim by the Latins that Jesus instituted the sacrament of communion at the Mystical Supper using the unleavened matzah of Passover, even if the meal was held at the beginning of the fourteenth of Nisan and not the end. Like I said, it can be neither proven nor disproven. Maybe He held it a day early knowing that He wouldn’t have the opportunity at the proper time. The Synoptic Gospels depict the preparing for a Passover meal, but they never expressly depict the meal. Christ’s last meal is depicted, of course, but so many details of it depart from the rules of the Passover: they sit down instead of stand (Matt. 26:20), they dip food in sauce (26:23), etc. Maybe that’s because this isn’t yet the Passover meal. If it were, though, with so many rules not followed (such as eating it a day early), why would Jesus be beholden to the use of unleavened bread? But then would Jesus have the disciples prepare a Passover meal and then not go through with the ritual, knowing that He Himself is the true Passover meal? Maybe He would. He tells the disciples to bring swords to Gethsemane, and then when they get there He says to put them away. The fact is we don’t know. I would normally go to the Church fathers to figure this out, but they give conflicting accounts (Siecienski 101ff). Some say He didn’t have a Passover meal; some say He did, even if it was a day early. Some say He had the Passover meal, and then He put it away and held the Mystical Supper as a separate, common meal.

The point is... historicity is not the point here. And it is wrong to make it the point. I mean, it should seem a little deliberate by now that the whole of revelation is using these ambiguities to pull us into a higher understanding. When it comes to Passion Week, we are gazing at the overpowering radiance of an eternal, paradigmatic event, even if it is rooted in time — really, it is the eternal, paradigmatic event, that which stamps its shape on all history, from beginning to end. According to chiastic causality, Christ creates the heaven and the earth, resurrects them, and judges them from His position on the Cross. Days that are in this close proximity to the primordial light of eternity will interpenetrate each other according to their equal participation in that light. Remember, time and eternity are undergoing, here at the chiastic summit of creation, an intimate marriage with each other, such that each takes on properties of the other. It’s like how Christ’s resurrected Body is observed to operate, once He reveals it to His disciples. In the locked room He eats fish and honeycomb and submits Himself to Thomas’s touch, activities proper to the nature of flesh. But His Body expands and contracts so as to enter and leave the room while the doors are locked, moving the way the mind moves, at the speed of thought, according to the activity of spirit interpenetrating it. It’s the same way with the days of Holy Week. Time by its own nature moves linearly and sequentially, but these days are observed behaving according to the eternal Day of the Lord active within them.

In Orthodox liturgical practice, the way these holy days bleed into each other is expressed in many ways. For example, on Holy Thursday, the occasion of the Mystical Supper is celebrated with a Vesperal Liturgy. That is, a Liturgy is held on Thursday, in honor of the events on Thursday, but it’s preceded by the Vespers service for Friday. So which day of Nisan is it? A Vesperal Liturgy again mixes days on Holy Saturday, the Great Sabbath, when Christ rests in the tomb and the Resurrection is celebrated as if it’s already present (because it is). Earlier in the week, the Mystical Supper at which Christ first communes His disciples with His Body and Blood is not merely an historical event, no more than Christ is merely a human being. Christ is both God and man, and the Supper is both historical and eternal. The Mystical Supper on Thursday is already the Pascha on Friday, regardless of what day it’s on, because it’s participating in the eternal feast, not just of Friday, but of the whole Paschal weekend as well as the fiftieth-day perfection of God’s revelation of Himself through the world — the Mystical Supper is already Pentecost, too. As we saw at Annunciation, how else can the Body and Blood of our Savior become incarnate except through the descent of the Holy Spirit? The Spirit of Pentecost hovers over the waters even at the dawn of creation (Gen. 1:2).

So how can an historical argument be made that Christ must have used the unleavened matzah of the Passover Seder for the institution of communion? Even to try to is to miss the point of the life-giving story (you know: life-giving, as in leavened). That’s why the point can’t be argued to any satisfaction. Meanwhile Orthodox polemicists against azymes have brought up the point that even if Christ did institute communion with matzah, it doesn’t mean the Spirit-filled Church ought to hold its communion the same way (Ware 118; cf. Siecienski 127n). That Christ was circumcised and observed sabbath laws and yet the Church doesn’t follow suit is widely accepted, for reasons explained in the New Testament. Even if historicity could be determined, the question would be moot! Really, since it’s primarily a symbolic, eternal event, one that contains the fullness of Pentecostal revelation, it’s likely the bread that Christ used also conformed to the symbolic reality. (And it should be noted the Greek text of the Gospel account has artos, not azyme, a weird and arguably erroneous word choice if Passover matzah were intended.) Reducing the symbolical, mystical union of eternity and time that is occurring in these paradigmatic Passion Week events to a mere historical chronology is like... well, it’s like removing the leaven from your communion bread. It’s like smashing the life out of it with iron tongs so that you can keep a self-willed streak of asceticism going.

We are what we eat

That’s the spirit of the Roman papacy since the time of the Great Schism. This use of technology in the making of the azyme wafers, the blacksmith’s iron tongs, contributed to clerical efforts to make the Eucharist uncommon to human life and therefore, supposedly, more sacred. Historically, that impulse has had the exact opposite effect. By the twentieth century there were manufacturers of Roman Catholic communion wafers (no longer made by the priests) that advertised as a selling point that their product had at no point in their preparation been touched by human hands. That which had been meant to be supersubstantial with us had, because it was not at the same time lovingly consubstantial with us, transformed into something utterly profane, consubstantial with lifeless machines. Packages of overproduced communion wafers mechanically manufactured for a consumerist culture have in places been sold on store shelves, to be purchased for any profane use imaginable, or else to be disposed of like so many excess embryos produced by test-tube fertilization.

The industrialized, mechanized, technologized world we live in is a product of centuries of azyme consumption in the Western churches; indeed our world has been begotten after the image of unleavened wafers. In the story of Exodus, Moses makes clear the Israelites ate unleavened matzah because they were in a hurry (Ex. 12:39). They were trapped in the exigencies of the moment and had no time for the bread dough to rise. Chased by death, they were subject to time, enslaved to it. But the objective of the exodus was to free them from those exigencies. Passover is merely the beginning of freedom, and maybe charitably it could be said that Roman Catholics yet partake in this aspect of the paradigmatic feast. But the beginning of freedom fails to rise to its fulfillment if it rejects the perfection of freedom. On the Pentecost for which Israel is destined, in both its aspects of Shavuot on Sinai and Bikkurim in the Holy Land, we the true Israel, freed from sin, the devil, and death, have more than enough time to introduce the new leaven of divine life into our daily bread; we have all of eternity. Of course our communal bread is leavened — leavened with the Life of the Spirit, unto life everlasting. In Christ, the beginning of freedom is already the perfection of freedom, and to confess otherwise is blasphemous.

Orthodox theology is an immense fractal image. If you get the Christological pattern wrong on any one level of the fractal, you risk that error spreading like spoiled leaven to all the other levels, until, like the Roman Catholic faith upon its cursed nativity a thousand years ago, you’re fractally wrong. On the level of epithymia: the unleavened wafers for communion. On the level of thymos: the enforcement of an exclusively celibate priesthood. On the level of logos: a dialectically determined Scholastic theology, with the Filioque Trinity as a centerpiece. On the level of the nous: the Luciferian presumption of power on behalf of the papacy, a pattern that plays out down the ranks in the form of clericalism, always placing a vicar in the way of anything divine.

Meaningfully, St. Mark of Ephesus wanted to start dialogue at the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438 with the issue of azymes (Siecienski 175–76). As a good Orthodox Christian, he wanted to go Beauty-first, recognizing epithymia as the bottom layer of this fractal schism, the point on which everything hinges. What is it that you desire? What do you yearn to consume? What is it that you love? Those are the questions that determine which way your soul goes. The emperor, however, blushed at such a suggestion, knowing the disagreement about azymes to be intractable. Overly eager for political help defending Constantinople from the Turks, he insisted on a Roman Catholic–friendly, Truth-first direction, starting with a year-long dialogue on the topic of the Filioque. The council was programmed from the beginning to come to Roman Catholic conclusions, and it did. In regard to communion bread, once it got around to it, the council declared the liturgical difference contained no doctrinal meaning — even as an unleavened wafer contains no spirit, it could be said. The Orthodox bishops participating in the council (those not named St. Mark of Ephesus) were swept up in the delusion, but the rest of the Orthodox world never fell for it for an instant. The false union never spread beyond Florence, and Roman Catholic assistance to Constantinople’s cause against the Ottomans never materialized.

For the last millennium, the popular aversion to unleavened communion wafers among the Orthodox has been a steady feature, and I believe it to be divinely inspired. We as a body instinctively know the orthodoxy of our faith in doctrine and in practice. I get that from a humanist perspective, such as the one to which the children of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation are beholden, it would appear we Orthodox are being arrogant schismatics, proudly behaving as if we have something special to protect that others don’t have, when we couldn’t possibly. We know, though, with great faith, that we do. The Orthodox Church in this world is a type of Paradise, a walled garden where, nevertheless, due to the free will invested in man, things can go wrong; sins can be committed, heresies can be hatched, schisms can be formed. But when they do, exile results, and the offending parties are expelled beyond the walls where good can mix with evil for a limited season. The sanctity of this perpetually blooming garden, which like leaven is the life of this world, if left to man’s devices would not be preserved. But the Lord the Holy Spirit Himself always maintains it, without fail, for Abraham’s sake, His beloved, for Isaac’s sake, His servant, and for Jacob’s sake, His holy one. The role that Israel played to the nations — which is the role Noah’s ark played to the descendants of Cain and Seth, and the role Paradise ever plays to the inhabited world — is the role played by the Church to all the earth. And the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.

Indeed, “Let the walls of Jerusalem be builded; then shalt Thou be pleased with a sacrifice of righteousness” (Ps. 50:18–19). Without the walls sectioning off this garden from its surroundings, the life of the world would be spoiled, and I thank the Lord for these barriers. Even if it means I myself may be cast out beyond them due to my sin, the preserved presence of those walls means there’s still life in this world for my loved ones, and mayhap for me to return to. The solution to being cast out beyond those walls can never be to break down the walls, as the Orthodox have a standing invitation to do by the Catholics. Those walls guard the Tree of Life. The Great Schism, on the other hand, is a model of death, which means it is a tragedy that should not be. All the same — like the Lord’s Death — I thank the Lord for it, and do so for as long as the Roman Church persists in its heterodoxy. Without that wall of excommunication, truly, I wouldn’t be alive.

Christ, the Bread of Life, is risen!

References

Ahmad, Joseph. “Leo Ohrid’s Three Epistles on Azymes: a study in symbolism.” Paper for a graduate course in Byzantine Liturgy at The Catholic University of America. Accessed on Academia.edu at www.academia.edu/113293440/Leo_of_Ohrids_Three_Epistles_on_Azymes_translation_and_introduction.

Critopoulos, Metrophanes. Confession of Faith (1625). Translated by Colin Davey. See Pelikan.

Erickson, John H. “Leavened or Unleavened: Some Theological Implications of the Schism of 1054.” The Challenge of Our Past. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1991, pp. 133–55. Accessed on Archive.org at archive.org/details/challengeofourpa0000eric/. Originally published in St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 14 (1970), pp. 3–24.

Graziano, Lucia. “Communion wafers instead of loaves: A history.” Aleteia website. February 7, 2023.

Leo of Ohrid. Three Epistles on Azymes. Translated by Joseph Ahmad. See Ahmad above.

Louth, Andrew. Greek East and Latin West: The Church AD 681–1071. St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2007.

Pelikan, Jaroslav and Valerie Hotchkiss, editors. Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition. Volume I. Yale University Press, 2003. Accessed on Archive.org at archive.org/details/creedsconfession0001unse/.

Runciman, Steven. The Eastern Schism: A Study of the Papacy and the Eastern Churches during the XIth and XIIth Centuries. Oxford University Press, 1955. Accessed on Archive.org at archive.org/details/easternschismstu0000srun/.

Siecienski, A. Edward. Beards, Azymes, and Purgatory: The Other Issues that Divided East and West. Oxford University Press, 2023.

Smith, Mahlon H. III. And Taking Bread...: Cerularius and the Azyme Controversy of 1054. Éditions Beauchesne, 1978. Accessed on Archive.org at archive.org/details/andtakingbreadce0000smit/.

Sveshnikov, Sergei. Break the Holy Bread, Master: A Theology of Communion Bread. Self-published, 2009.

Ware, Timothy. Eustratios Argenti: A Study of the Greek Church under Turkish Rule. Oxford University Press, 1964. Accessed on Archive.org at archive.org/details/eustratiosargent0000kall/.

Thank you