I. A Metahistorical Feast

II. Between Pascha and Pentecost

III. A Chiastic Feast

IV. In the Midst of the Waters

V. A Revelatory Feast

I. A Metahistorical Feast

There is no way to understand the Church’s feast of Mid-Pentecost on a plain historical level. It is celebrated on the 25th day of Pascha, halfway between that Feast of feasts and Pentecost, the fiftieth day. Yet there is no biblical event associated with this point in the liturgical calendar. The Gospel reading prescribed for Liturgy, John 7:14–30, begins with “In the midst of the feast…”, but contextually that passage refers to the autumnal Feast of Tabernacles in the month of Tishri, not to vernal events like Passover or Pentecost. Nonetheless the service book (the Pentecostarion) adds to the text so that it says, “In the midst of the feast of Pentecost,” which I assume is representative of how it was copied in lectionaries for this specific feast day, if not in actual books of the Scriptures themselves.1 The traditional icon for Mid-Pentecost, on the other hand, goes in a completely different direction, depicting Christ at age twelve astonishing the teachers at the Temple with His wisdom after the Feast of Passover and Days of Unleavened Bread (from Luke 2:41–50).

This mid-feast feast is plainly unmoored from history and challenges the faithful to understand it by other hermeneutical means. After His Resurrection from the dead, Jesus remained with His disciples, appearing to them in His resurrected Body from time to time up until His Ascension on the fortieth day. When visiting them, He would call to their minds all the things they saw and heard concerning Him previously, along with all the things they had been taught out of the Holy Scriptures, from which they could now see and understand the fulfillment of all creation. The common theme throughout all liturgical aspects of Mid-Pentecost, therefore, is the Son of God sojourning among His people in the flesh, and, in a metahistorical way, the Church reflecting on all the instances in history when that pattern recurs, acclimating themselves to a divine perspective of the cosmos. The Old Testament readings at Vespers depict, (1) from Micah, the Lord having a controversy with His people and pleading with Israel as someone subject to their behavior; (2) from Isaiah, the counsels of Lord being likened to waters of salvation coming down from heaven and saturating the earth, returning as vegetation, as seed for the sower and as food; and (3) from Proverbs, Wisdom (to be identified with Jesus) building a house and preparing a feast of flesh and wine, calling to attend all those who languish in foolishness. Mid-Pentecost, as with other high-ranking feasts, is understood as the fulfillment of its Old Testament readings. But the historical event we appear to be celebrating is when the disciples of Christ first began to contemplate historical events in the light of His presence — a contemplation that begins but never ends and into which we in the Orthodox Church enter liturgically no differently from how the disciples did so historically.

II. Between Pascha and Pentecost

“The middle of the days is come, which beginneth with the Savior’s arising, the end whereof is sealed by the divine Pentecost, which is illumined by the radiance of both, and uniteth both; and showing forth the glory which is to come, it honoreth beforehand the Master’s ascension.”

– Vespers for Mid-Pentecost, first sticheron of “Lord I Have Cried”

This verse above is how the feast opens.2 Pascha is Passover, the rescue of Israel from slavery in Egypt, an image of God saving mankind from death. Pentecost, or the Feast of Weeks as it is also known, is the fiftieth day, when after a week of weeks (seven times seven) God gave the Law on Mt. Sinai and Israel became a nation wedded to the Lord in a holy covenant. The number fifty is a magnified image of the number eight, the number after a cycle of seven, which transcends the temporal order of this world and begins a new cycle of the same on an elevated, deified plane. In Mosaic Law, Passover was marked with the Feast of Unleavened Bread, whereas Pentecost was marked with the offering of loaves of leavened bread (Lev. 23:17) — the leaven here prefiguring the presence of the Spirit who was to come and transform human life in the body of the Church. On Pentecost the Spirit of the Lord imbues the disciples of Christ, forging a new people, a new law, a new covenant, one written not on stone but on the fleshy tablets of the heart.

Mid-Pentecost lies between these two festal extremes, mediating between them in an image of Christ, consubstantial with the Father and the Spirit, present in the Temple among us, mediating all extremes together in Himself. At Matins there are two canons celebrating the occasion, the first of which is the more contemplative. It reads at its own midpoint, at Ode V, “Truly sacred is this solemnity of the midfeast, for it is the root of the all-great feasts, and deriveth light from both of them.”3 Thus the feasts of Pascha and Pentecost, despite being different days, are presented as one organic motion of the divine economy, like two burning bushes with a single root; Mid-Pentecost is the celebration of that hidden unity. Its light is not its own but is derived from the two incandescent bushes. Of that light we learn in the next ode, “The mid-point of Pentecost hath dawned today, shining forth with most divine splendor from the divine Pascha, and from thence spreading the light of the grace of the Comforter.”4

All these verses I’ve quoted so far are suggesting a chiastic causality, saying not only that a feast is shining forward its light 25 days in its future, but also that the light of a feast that has not yet happened is filtering back in time to its root 25 days in its past. I’m sitting here, thinking that this is the first time I’ve thought to use the term “chiastic causality,” and wondering what took me so long. (I’ve already described it, in “The Cosmic Chiasmus,” but I didn’t use the term.) I’d like to point out that it was Mid-Pentecost that finally brought it out of me.

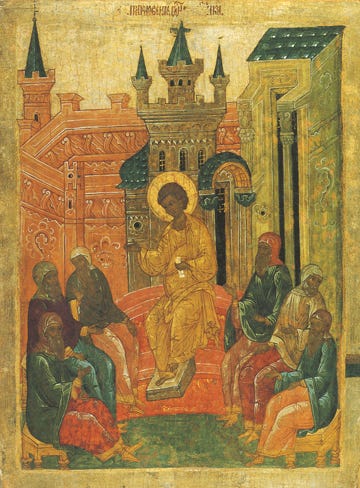

Above is a 14th-century fresco from Pech, Serbia labeled “The Midst of the Feast” from John 7:14, which illustrates the events from John 7 used for the hymnography of Mid-Pentecost. Notice the figures are arranged linearly from left to right, but facing forward and backward towards the middle, where we see a man — who is “God with us” — reading from a holy book, hence centering both God the Word and the contemplation thereof. In its final ode, Canon I of Mid-Pentecost reads, “Having clothed my mortality in the raiment of immortality and the grace of incorruption, O Savior, Bestower of life, Thou didst raise it up with Thyself and bring it to the Father, bringing an end to my temporal warfare.”5

Therefore the lights of Pascha and Pentecost which chiastically illumine Mid-Pentecost are also rays of divinity. As heard at Ode I, “Thou didst come at the mid-point of the feasts, O Christ, manifestly emitting the splendors of divinity; for Thou art the joyous feast of the saved and the Mediator of our salvation.”6 Of course, if the feasts are two but also one, then this dynamic is surely an image of the begotten Christ and the proceeding Holy Spirit being two in person, one in essence. And the cause of their unity is the person of the unbegotten Father, to whom we are united by means of the whole Filial–Spiritual, Paschal–Pentecostal liturgical complex.

III. A Chiastic Feast

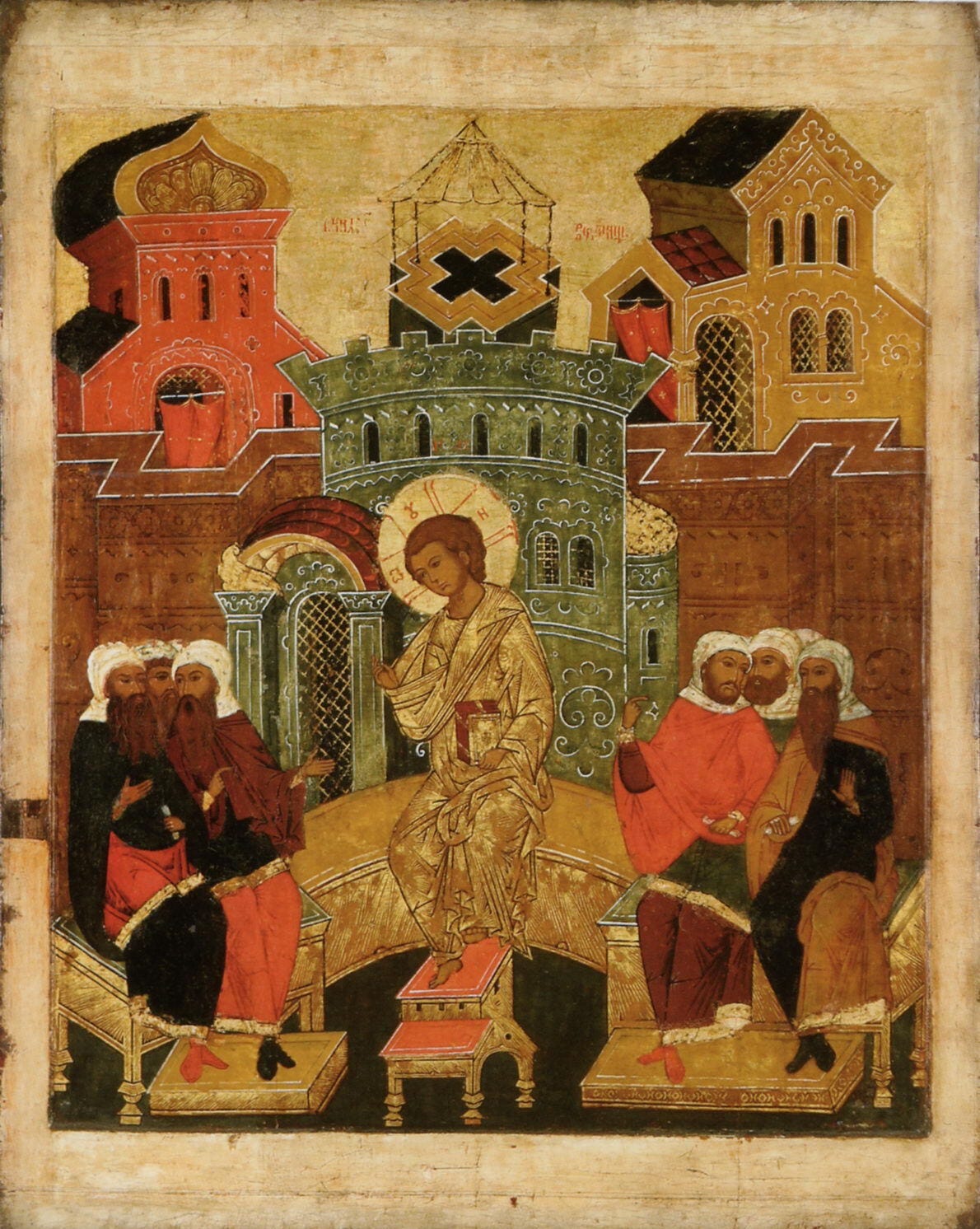

This is my favorite icon of Mid-Pentecost for how fractally chiastic it is. The image is even crowned with a cruciform, Χ-shaped temple. To describe it in my paltry words would feel like a diminution. I would prefer just to invite the reader to contemplate it along with this verse from Canon I, Ode IV, “As Thou Who art without beginning holdest the beginning of all things, and their midpoint and end, Thou didst stand in the midst, crying out: O ye divinely wise, come and enjoy the divine gifts!”7

IV. In the Midst of the Waters

So the icon of the feast is from Christ’s childhood in Luke 2, and the Gospel reading (John 7:14–30) is from the middle of the Feast of Tabernacles, the one major feast of Israel that is neither Passover nor Pentecost. Furthermore, the liturgical service’s favorite line to repeat is from John 7:37, still from the Feast of Tabernacles, but now not even from the middle of that feast but at the end. John 7:37–39 reads,

In the last, great day of the feast, Jesus stood and cried, saying, “If any man thirst, let him come unto me and drink. He that believeth on me, as the scripture hath said, out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water.” But this spake he of the Spirit, which they that believe on him should receive: for the Holy Spirit was not yet [given]; because that Jesus was not yet glorified.

So at the middle of the feast we look towards the end of the feast, the promised receiving of the Holy Spirit. The words of the troparion (main hymn) of Mid-Pentecost go, “In the middle of the feast quench Thou the thirst of my soul with the waters of piety, for Thou didst cry out unto all, O Savior: ‘Let him who thirsteth come to Me and drink!’ O Christ God, Thou Wellspring of life, glory to Thee!”8 The kontakion (secondary hymn) evokes the same message: “At the midpoint of the feast of the Law, O Christ God, Creator and Master of all, Thou didst say to those present: ‘Come and draw forth the water of immortality!’ Wherefore, we fall down before Thee and cry out with faith: Grant us Thy compassions, for Thou are the Source of our Life!”9

The following 14th-century fresco from Visoki Dečani Monastery in Kosovo illustrates this main hymnographic theme of Mid-Pentecost, reading at top, “Whoever thirsts, let him come to me and drink,” and featuring Christ holding an amphora at his midsection.

The Sundays following Pascha are all taken from the Gospel of John, and following his lead heavily feature watery themes. During this time, moreover, every week is treated liturgically like an afterfeast of the preceding Sunday, its canon at Matins being repeated every day along with the saint from the Menaion. The eight-day celebration of Mid-Pentecost occurs like another week-long water-themed feast laid on top of this pattern. In the back half of the Week of the Paralytic — healed besides the miraculous sheep pool at Jerusalem — canons to both Mid-Pentecost and the Paralytic are read at Matins, for example, and for the first half of the Week of the Samaritan Woman — who was met by Christ at the well where they discussed the water that ends all thirst — she too shares her spotlight with Mid-Pentecost (until, that is, the leavetaking on Wednesday, the eighth day of Mid-Pentecost).

Waters are laid upon waters, like waves upon waves. What I had previously discussed as a confluence of light, is for a large portion of Mid-Pentecost’s imagery described as a confluence of waters. Whereas the imagery of light references a theological vision, the imagery of water gives way to a cosmological vision. The second canon of Mid-Pentecost focuses on events in and around John 7 and contains multiple references to water — but more so, it is symbolically watery in shape. That is to say, the canon is historical in its attention, embedded within a temporal perspective, and constantly calling to mind the lack of faith, like a liquidity of soul, with which the Messiah was met by His people.

“If the Messiah must needs come,” the second canon reads, “and Christ is the Messiah, why, then, O ye iniquitous ones, do ye not believe in Him? Behold, He is come and beareth witness to the things He hath done: He hath turned water into wine and restored the paralytic by His word.”10 Again, Mid-Pentecost was a time when the disciples of Christ, illumined by His victory over death and anticipating Ascension and Pentecost, reflected on the centrality of Christ’s presence in history and their own unworthy response to Him. As I wrote a month ago during Holy Week, in our liturgical texts, anagogically understood, the Judeans represent the best of us. The disciples all fled at the time of Christ’s sacrifice, and had cause to rebuke themselves for what they had done. The Church continues their repentance apace when it anagogically contemplates verses like these: “‘Be ye not ones who judge by appearances, O Judeans,’ the Master said, teaching, when He went to the Temple, at the midfeast of the Law, as it is written.”11

It is interesting: I mention how the second canon of Mid-Pentecost is embedded in a temporal perspective, and in fact it scarcely makes reference to Pentecost and the Descent of the Spirit at all. Its midpoint, at Ode V, presents a big exception when there is hymned the glorification of the apostles in all the world, to its enlightening, consequent to Pentecost though without mentioning it or the Spirit. Otherwise, however, the canon is meditating on past events when Christ, the fulfillment of the Law and the Prophets, stood in the midst of His people striving with them and counseling them, calling them out of their unbelief. I called the first canon of Mid-Pentecost more contemplative, and so it is explicitly anyhow; yet the second canon still narrates the act of contemplation and can’t be understood except contemplatively. And, focusing on the temporal history of the incarnation, it can’t but be led back up to a timeless theology. The verses of Ode VI read,

O Jesus, Who sustainest all the ends of the earth, Thou didst go up and teach the word of truth to the people in the Temple at the mid-point of the feast, as John crieth out.

Thou didst open Thy lips, O Master, and preach to the world the timeless Father and the most Holy Spirit, with both of Whom Thou didst preserve Thy kinship even after Thine incarnation.

Thou didst do the work of the Father, and didst lend credence to Thy words by Thy deeds, working healings and signs, O Savior: restoring the paralytic, cleansing lepers, and raising up the dead.

The beginningless Son received a beginning, assuming our humanity when He became man; and at the mid-feast He taught, saying: “Haste ye to the ever-flowing fountain, and draw forth life!”12

Thus the waters of unbelief below are met with the water of life from above — even as their Source spouts forth in their midst, another instance of cosmological chiasmus, fractally layered.

V. A Revelatory Feast

Soon in our liturgical cycle, Ascension and Pentecost are to be revealed as unified: the ascent of the Son and the descent of the Spirit, witnessed across a span of ten days, are yet like two ways of perceiving the same thing (cf. John 16:7). Then, according to a chiastic causality, Mid-Pentecost reveals that that eschatological movement and Christ’s Death and Resurrection are also one economic motion. From within time we perceive the colors of this light spread across fifty days as in a spectrum. But from the perspective of eternity, the eternity we enter when we are joined to Christ, it’s all one brilliant white light. On the very day of Pascha, after all, in the evening, in the locked room, Christ appears to His disciples, breathes on them and says, “Receive ye the Holy Spirit” (John 20:22). Insofar as He has not yet ascended, this is not yet Pentecost. But insofar as Christ’s Resurrection is already an eschatological event, He is already ascended, and Pascha already contains Pentecost. Both tracks, the temporal and the eternal, are active in this story. By means of God the Logos’s mediation, both eternity and time occur within each other.

Mercifully, the doxasticon for the Praises at the end of Matins for Mid-Pentecost grounds us again in anticipation, that we fail not to mediate our temporal existence with the eternity we are entering: “Having been enlightened by the resurrection of Christ the Savior, and reached the midpoint of the feast of the Lord, O brethren, let us most ardently keep the commandments of God, that we may be worthy to celebrate also the ascension and to receive the coming of the Holy Spirit.”13

Often neglected, Mid-Pentecost is an amazing event in the liturgical calendar. If, as the hymns have demonstrated, it contains the light of both Pascha and Pentecost, one might wonder why it is not even more revered than either of those events individually. It’s not a vigil-rank feast; it’s not even a polyeleos-rank feast. Though featuring Old Testament readings at Vespers and a week-long afterfeast, Mid-Pentecost itself is celebrated merely as a doxology-rank feast. That’s, like, the middle tier of the festal ranks — appropriate enough for a Mid-feast apparently! For the divinizing works of the divine Trinity are still best celebrated in themselves, in their historical instantiations, not in their unity accessed in our minds through the art of reflection. Our Christian contemplation can be celebrated for its Christianity (for this too is the Spirit and Christ working in us), but surely not more than that which we contemplate. That which deifies is infinitely more admirable than that which is deified, and no one being deified can ever forget it. Comparing the two is like comparing a twelve-year-old Christ astonishing teachers in the Temple to the fully matured Christ crucified, risen, and ascended.

On the Sunday in the midst of the middle-ranked mid-feast, the reflective quality of Mid-Pentecost receives its strongest image and its most faithful evaluation. The Church prays,

The most holy, luminous and beauteous mid-feast of the resurrection of Christ is manifest today like the radiant moon, enlightening the world with the divine graces of the rising of Christ, emitting miracles of incorruption; and it shineth forth signs and pointeth to the ascension on high, revealing the most loving advent of the Spirit, the most splendid solemnity of the most honored Pentecost. Wherefore, it giveth our souls peace and great mercy.

It being the mid-point of the feast, the Lord, giving streams of compassion unto all like a river of divine glory, crieth out: “Let him who thirsteth come to Me and drink with fervor.” For, as a wellspring of compassion and an abyss of mercy, He poureth forth remission upon the world, washeth transgressions away, and cleanseth infirmities; He saveth those who celebrate His resurrection, and He covereth with love those who honor His ascension with glory, and He granteth our souls peace and great mercy.14

The Pentecostarion of the Orthodox Church, trans. by Isaac E. Lambertsen (The St. John of Kronstadt Press, 2010), p. 150. All notes are from this volume.

Vespers for Mid-Pentecost, at “Lord I Have Cried,” p. 139.

Mid-Pentecost Canon I, Ode V, p. 144.

Ibid., Ode VI, p. 145.

Ibid., Ode IX, p. 148.

Ibid., Ode I, p. 142.

Ibid., Ode IV, p. 143.

Troparion of Mid-Pentecost, p. 141.

Kontakion of Mid-Pentecost, p. 145.

Mid-Pentecost Canon II, Ode IV, p. 144.

Ibid., Ode II, p. 143.

Ibid., Ode VI, p. 145.

Mid-Pentecost Matins, doxasticon at Praises, p. 149.

Week of the Samaritan Woman, stichera of the Midfeast at Sunday evening Vespers “Lord I Have Cried,” p. 179.

Thank you Cormac! This was wonderful to re-read.

In excitedly revisiting this, the question arises: do the nine Biblical odes of Orthros form a chiasm?

Χριστός Ανέστη!

Chiastic causality - awesome! Now that you've coined it, it does seem like an obvious phrase. Funny how that works. Great article too - very skillful weaving between the temporal and eternal.