Chiasmus as camera lens for the infinite

Thoughts on a life spent in difficulty communicating, as illustrated by some adolescent art photography

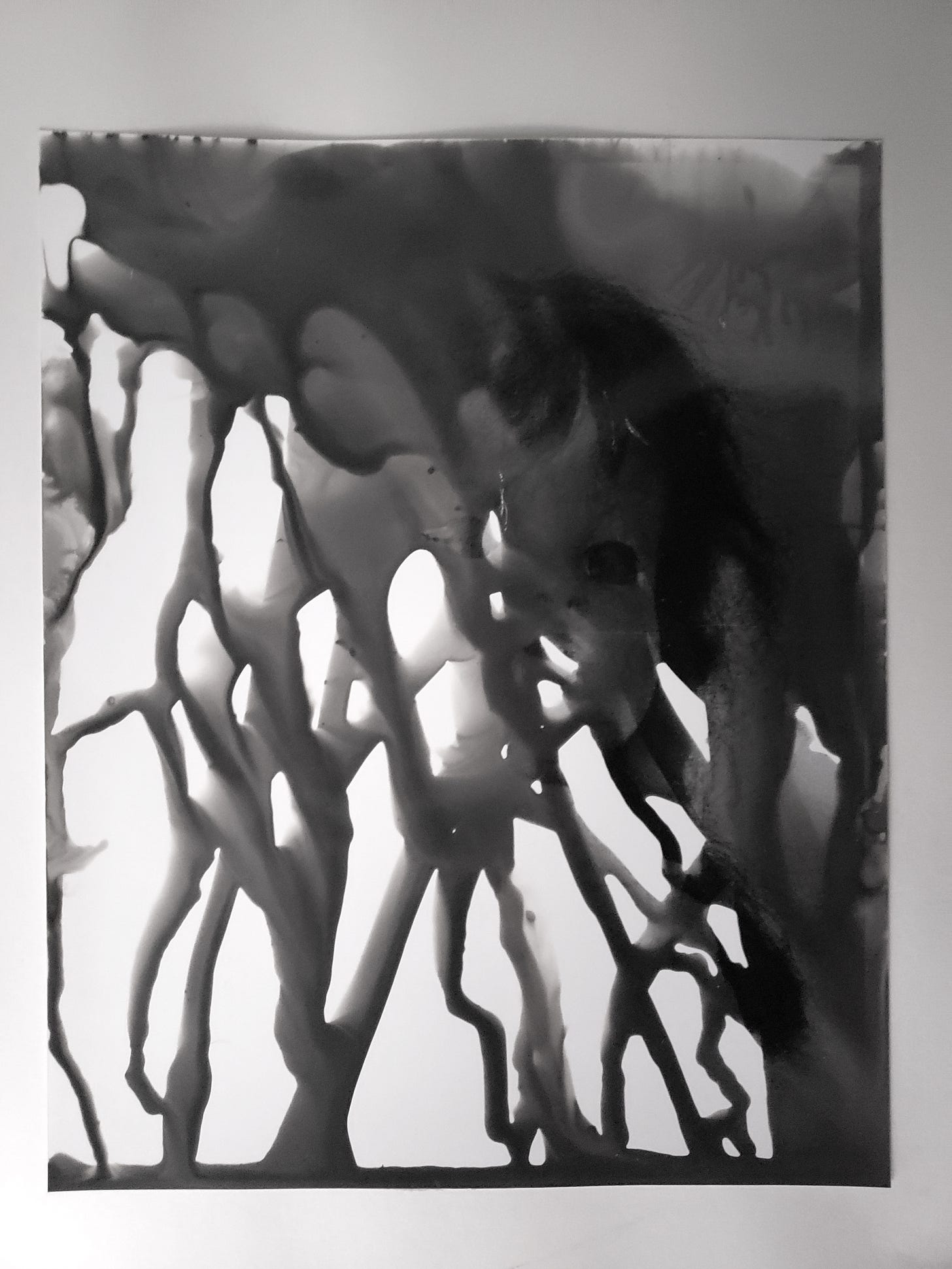

I was years away from learning about chiasmus or being conscious of it in any way, but already at age 17 the form was naturally occurring to me. I created the above series of five photographic prints, to be presented in this symmetrical order. I forget my thought process exactly, but I know I was trying to tell some kind of story visually that had a left-to-right directionality but was to be contemplated together visually in a single, circular composition. Here is the first image:

I emphasized the linearity of the project, the temporal quality, by linking each image to a song by Low, by then my favorite band and a chief influence. Tragically I don’t remember which songs went with the images, but I can make a good guess. It was late fall 1997, so I would have been working primarily from the albums Long Division and The Curtain Hits the Cast, though I believe the central song (the one I’m most certain of) was from their latest release, Songs for a Dead Pilot. Listening to the songs is ancillary to this essay, but anyone interested will find in the captions of the images YouTube links to the songs I’m picking, or for those who prefer Spotify, a playlist at the bottom of the page.

Only in time can one listen to music, but imagine looking at a playlist of five songs and contemplating them at once, as though visually, knowing their order and their progression through time, yet not being restricted by it, being free to explore around inside them like an image. With this photography project, the effect I was reaching for was nothing less than the hierarchical unity of time and eternity, which I wrote about recently in regard to the octave shape, but which is visible also in the basic premise of a chiasmus. The Gospel of Matthew is a prime example: The structure is clearly parabolic, having as an apex the parables of the kingdom of heaven, which explicitly operate like seeds containing the whole, planted from above by the pre-eternal God. Yet the structure is also entirely linear, telling a story in time about the life of a Man on earth, from His virgin birth to His deathless death. When eternity is planted in time and time is given to express eternity, on the material level, chiastic shapes naturally appear. I think of the phenomenon as a kind of lensing effect that imprints the eternal onto the material world.

On account of my mother’s artistic influence, I’ve always had a strong sense for the visual, the ways information is conveyed through light and space. Attempts to be creative in visual media, however — to connect the heaven of my perception with the earth at my hands — have not been successful. I never, not once in my life, took to drawing, despite my mother being an art teacher. As a child I loved Legos because I loved seeing forms snap into place, but then I was the type of kid who took pleasure solely in following the provided directions, never creating my own structures, never actively discovering the forms myself — my psyche has never seen sculpture as an option. As a teenager I may have attempted photography, but I could never form any lasting bond with the photochemical mechanics of the technology to control what I was doing. As regards technique, the heaven of my ideas just was not connecting with anything in the material world. The best I could do was reflect that disconnection.

Let me illustrate what I mean. I could be walking in a park, and I’d come across a place in the landscape where the beauty of space as it was arranged around me would reach through my vision and inspire my heart. I’d lift the camera to my eye in attempt to communicate the experience, but no lens in my possession could capture what I was seeing so as to achieve the same effect. This is what a camera lens does: it takes the three-dimensional experience of space and converts it into two-dimensional images. Great photographers are those who excel particularly at this conversion process — it’s not at all enough to have a great eye for beauty as it exists in three-dimensional space. For a photographer, knowing what looks great in the eye is a worthless talent if you don’t know what looks great in the lens. I believe it’s even possible to communicate those inspiring experiences in two-dimensional images using for fodder three-dimensional space in which the same beauty doesn’t register. It can be created from scratch with the lens if you know where to point it.

One of my sisters took up photography, and she had the knack; she went to school for it and became a professional. She’s a wonderful photographer. The same knack never happened to me. In high school I would take my rolls of film from the camera, full of unsatisfactory images, and try to find inspiring things to do with them in the dark room. But it was all experimental and chaotic — accidental. Beauty requires some iota of order and purpose. Otherwise all you can express is fragments of human experience deprived of intelligence, not invested with it, and hence dehumanizing. I didn’t want to make dehumanizing art. But I could only achieve so much, only communicate so much, without having any mastery of my tools.

So, unable to communicate in any visual media, I resort to words instead. Writing is the homely common-law wife I’ve settled down with, but with whom I don’t always get along — perhaps because part of me still pines for the dazzlingly beautiful woman in my life who keeps me forever in the friend zone. But also the strain in relationship is due to the persistence of the lensing problem, analogically speaking. When communicating in words, the need to convert multidimensional ideas into single dimensions of thought remains. Whether writing or speaking, it’s imperative to craft a line of words that goes from point A to point B. It’s just one dimension — you don’t even get two, as with photography. Yet my experience of ideas is multidimensional. It’s the same problem! As I stroll along in the park of my mind, I commonly find myself amidst gorgeous landscapes of ideas. The inspiration is frequently overwhelming. In such a condition, giving gratitude to God for this shower of noetic light is of utmost importance. The soul requires it. But secondarily the soul also requires some form of communication with my fellow humans. The light has to be shared. The Lord shares it, and the natural impulse for all humans is to be like the Lord in whose image we are made. The impulse for this proliferation is as basic to nature as plant growth. We must grow in the likeness of God; we must be fruitful and multiply. Barrenness is the cause of great sorrow because it indicates a separation from God.

My ideas spin out, as they are doing know. This is the lensing problem. How can I write or speak linearly when my mind lives in non-linear space? By the power of vertical anagogy and horizontal analogy, my mind thinks in the shape of branching crystals and bubbling foam. What lens can faithfully convert such images to linear expression? Practically speaking, whenever I manage to express one thought and it’s time to express another, in which direction do I next turn? Visually, the thoughts spread out in multiple directions, but in words I can only choose one. Without a lens to trace a linear path for me across the facets of the crystal I’m beholding, I can become verbally paralyzed, and a veil of loneliness shrouds my heart.

In my struggle to communicate, I’ve thought about branching out into making videos. Writing is so hard and takes so long, and there aren’t as many readers in the world as there are viewers and listeners. I have a blessing to try this, but I hesitate to go forward. Speaking is supposed to be easier than writing, yeah? But expressing ideas by means of speech can be particularly distressing for me. Speaking requires spontaneous, free-flowing linear expectoration. In the face of this task, I often stammer and freeze. I’m a reader in the Church and handle chanting and singing with proficiency, so I know that my tongue works, at least when it’s locked into the grace of the Church’s prayer life, with all the words provided, and in such glorious form....

From this point, my thought diverges in different directions. I could go on to say, “And sometimes, it’s true, I am touched by grace to be as witty and eloquent when speaking spontaneously as I know I can be when given the time to write,” and then remark on the irony that I’ve come around to describing writing as easier than speaking. In what way is writing easier than speaking, since it takes so much more effort and time? And those thoughts could lead me down one path.

Another route would be to say, “My soul has always wanted to make films — whenever, that is, my spirit gives it respite from monastic aspirations.” And then I would remark on the irony of returning to literal lensing problems, the difficulties of filmmaking technique looming within even the simplest video. I could cite the filmmaker John Cassavetes, whose relationship with his medium was as ad hoc as mine would be, and who expressed frequent frustration with cameras for getting in the way of the movies he wanted to make, as if he could make movies without them. You can’t get around the need for a lens, or for the skill required to use it.

And that would be a different path. Because I’m taking the time to craft this in writing and I do in fact have a lens for writing that I know how to use, I don’t mind mentioning both paths — I know they both bend around to the same place, or can be made to. But when I don’t have a grip on the lens, as is often the case when speaking, I stall at the crossroads and drift into a lonely, bodiless place between the paths. It’s an image of death, and I don’t care for the experience, as comfortable as I’ve made myself in it my entire mortal life.

In my youth, as a teenager, I made some bad photography, and I also tried writing — screenwriting. I was so moved by my experiences, by my vision of things, my ideas, I wanted to draft out the movies in my head in the form of scripts. I had confidence in my feel for scenes, for images, for characters and dialogue. Jim Jarmusch taught me story didn’t have to come first. Fyodor Dostoevsky taught me characters could be mostly static, provided the ideas were engrossing enough to distract from the lack of character development. I was certain that if I nurtured my strong impressions of details, a potent enough story would emerge from them.

That’s how my essay writing worked for school, which is the genre and venue in which I first learned to write. An essay for school, I was taught, should have an introduction with a thesis statement, three body paragraphs each featuring an argument supporting the thesis, and a conclusion restating the thesis. It’s already quite pentadic! But I couldn’t start with a thesis. Operating in Word Perfect software, I would avail myself of the non-linear approach to editing. I would just jot down whatever observations struck me about the subject at hand. Then if I had trouble continuing a thought, I’d stop and write another. Connections would appear, and I’d click and drag and edit. (It’s how I’m writing this very paragraph!) Eventually a form would develop. Only once I knew what I was introducing could I write an introduction. Then I’d push myself to write a conclusion that did more than just restate what was said but brought the paper to another level. Things came together when I worked this way. I assumed the same would happen with my screenplays.

But the stories never emerged. What in non-fiction writing is a thesis or an argument, in fiction writing is a story. They are very similar. But the stories never emerged! I followed Jarmusch’s method of adopting a generic form to house my poetic observations, like a road trip or a basic three-act structure. Yet the catharses I perceived in my mind were not appearing on the page. The pages weren’t rising up to meet them. My lens wasn’t working. I had a trilogy of screenplays I was working on, but I trashed them all when I encountered the Church and her monastic life. I don’t regret not having them today.

In the Church, after college, with my back turned to creative endeavors, I happened to be shown the lens for writing that I lacked all along. In Scripture and in liturgics I found the patterns of cosmic organization. Besides being 100% ensouled with eternity and embodied in time, they’re chiastic and fractal and triadic and ogdoadic, and all the things I write about today. Aware that this perspective of Scripture was inclusive of subjective hermeneutics and so couldn’t be deductively “proven”, and that it ran completely afoul of academia’s deconstructive approach, I saw no path to developing the ideas publicly. Eventually I practiced using these lenses creatively by crafting song playlists, like making a movie out of found footage. Then it occurred to me that a way to demonstrate the power of these lenses would be to use them in the composition of original fiction. I began to see stories in my mind. They were in the form of movies, but they weren’t just movies; they were stories. The whole crystalline shape of them occurred to me all at once. And I saw how a chiastic lens could be used to convert the crystals into a linear form.

In a linear story composed fractally according to patterns chiastic or triadic or some ogdoadic combination of the two, multidimensional information can be successfully compressed into a single line of communication. A noetic experience can be conveyed by material means. Fractal and chiastic patterns do not need to be consciously recognized by readers/viewers in order for them to feel their benefits. Appreciation happens naturally because the patterns resonate with the structure of the cosmos. Creators themselves can frequently be unaware of the patterns; gifted intuition suffices for lack of conscious architecture. Jonathan Pageau’s version of Snow White and the Widow Queen, for example, has a beautiful and potent chiastic structure that he did not develop knowingly. I myself didn’t know what I was doing when I created this series of five photographic prints with the subject of the doll, or a few years later when I devised my chiastic Descartes paper.

In all likelihood there’s no substitute for this natural artistic instinct, as if it could be replaced by a mechanistic understanding of chiasmus. But neither is it necessarily hurtful to be cognizant of the form while creating. It can be immensely helpful. Sometimes I can write without being conscious of structure, but I commonly can’t. My recent essay “In the intermediate state of the soul after death, we’ll have no eyelids to close” — there are a thousand different renditions I could have made of it. At each point my thoughts spread out in multiple directions. Certainly more refinement could be done, but in order to create something passably concise and tight I had to keep trimming excess ideas that didn’t lead directly where I knew I next needed to go in order to keep it brief. I knew where I needed to go because I had already perceived what lens had to be used to capture the beauty of the idea. And not with abstract calculation did I perceive the proper lens, but with the same artistic instinct that I would use to pick one word instead of another, just on a macroscopic scale.

We call it writing, but it feels to me much the same as reading, like reading an idea with acuity. It fascinates me endlessly how there can be overlap between the disparate activities of authoring a fictional story and critically assessing something that already exists, how artistic creation and critical perception can be the same thing, perhaps just on different levels. The common factor is the lens. I use forms like chiasmus to help me both to understand what is written and to write myself. It often feels like the same thing. In either case a communion of heaven and earth is formed, between the eternal and the temporal. I feel blessed by God and connected to the life of the cosmos He has created and that He continues to create — a life that bears fruit and is not barren — whenever this happens.

My first completed screenplay took arduous work. My second flowed freely and quickly. While I was writing the second one, I was at the same time discovering Jonathan Pageau’s YouTube channel. Here was a context this man was creating in which I could potentially speak and be heard. He was doing the impossible but what had to be done; he was creating an audience (from scratch, it appeared to me) that could understand heavenly things on the earthly plane. Meanwhile no one was reading my screenplays, and I knew no one was going to. No matter how much I was taken with what I had written, the audience for meaningful cinema from new voices had been successfully eliminated by the forces of sterility in command of our culture. Movies nowadays are only ever made for preexisting audiences. No one’s ever going to fund what they don’t already know how to sell. The creation of new cinema today requires nothing short of creating a new audience — and in an historical moment of virulent sterility. I... that’s... If I had the talent to do that, it has yet to make itself known to me, let’s just put it that way. I don’t want to prevent the grace of God, but c’mon, who do I think I am?

Jonathan was achieving that, however, creating a new audience. So I landed on the Symbolic World as a contributing author to the website, writing essays instead of fiction. I’ve since pivoted to editor of the site and writer on Substack. I have another unfinished screenplay I care about deeply, one I started before the other two, but I haven’t worked on it for a couple years now. The point has always been about communication. I’m not content to write just for myself; I strive to serve an audience. People won’t read screenplays, but they’ll read online essays. So that’s what I’m doing. I’m perfectly pleased to do whatever I’m supposed to be doing, and that’s what I strive for. Lately, however, I struggle to discern what that is.

Under my editorial leadership, activity in the article section of the Symbolic World website has withered and slowed to a crawl. Maybe not all of that is my fault. There aren’t not extenuating circumstances. But the way I’ve responded to the challenges I’ve faced certainly must be playing a large role in the decrease in activity. Meanwhile, according to the metrics Substack provides, the past couple months as I’ve pivoted to writing about the octave, growth of the Journal has stalled and is sagging. Money I’ve received from subscriptions is much appreciated, but quite far from transformative. I still admire the readers that I’ve retained — very much, in fact; I have more than enough to keep going if that’s what I’m supposed to do. I merely mention it because, insofar as I’m no longer seeing growth, I have less indication than I used to that this is in fact what I should be doing. I’m saddled with uncertainty. I lived in a monastery once; I’ve known life-giving obedience. In exile from that, I’m not not going to feel its absence.

That’s not to say I look towards my audience to perform the role of my hegumen. I know that it can’t. But when I write I do have my audience in mind. I think, rightly or wrongly, Oh, Adam will like this, or, Kenneth will respond well to this. Does Glennis still receive these? I can’t imagine what she makes of any of this. What will Katie get out of this? Will Paul find this musical analogy meaningful or ignorant? Will David read and like this? Or David? (There are two.) What effect will this have on Silouan or Iakovos? (Though I think a couple weeks ago I failed to ask what effect it would have on Silouan. And sorry, James, it’s easier for me to remember you as Iakovos!) Peter, Max, Frederic — what do they see in what I write? Melissa? Lisa? Matthew? Cameron? João? Will Derek be able to get through this without thinking of Arrival? Unlikely! Is Diana still following along? Caitlin? Other Lisa? Is this piece worthy of their attention; is it inspiring enough? Will this inspire Colin to make something with his hands the way I can’t? Will Mark like this? John? What’s Sean up to? Has Elizabeth stopped reading? Is Dylan still around? Forget what Jean-Philippe or Annie think — how are their families doing? Treydon’s sometimes reading now; how does my thought fit into his? An old friend canceled his subscription. Is it my fault for not reaching out? More canceled subscriptions — did they come for cultural commentary and leave when things got too biblical and liturgical? (Or is it ... me.) Some new subscriptions — what are they coming for, and what do they expect?

I’m not chasing fame here. For example, I’m not going to pursue conflict as a means for exploiting people’s attention. And with more attention would come more scrutiny, and I wonder sometimes if more adversarial audience members would be at all helpful at this juncture or just counterproductive. “The important thing is to get the work done.” “Keep plugging away and don’t let up.” That’s what I’m doing, but should I be? Are those valid thoughts for this moment? Is that constant aching feeling in the background of all I do merely a result of my missing the virtue of obedience, without which there can be no peace? Is that the lesson? When’s the time to try to do something about that? Now? Or not yet?

Yes, the time is now, and yes, the time is not yet. I can see fairly easily that I’m still in the omicron stage of my life, that the omega era is a few years away yet. My lens is pretty clear about that. Now is the season to be fruitful; judgment will come later. There likely will come a time when the creative mission of connecting heaven and earth will have to be sacrificed for the sake of staying connected to the God of both. That’s the mystery of Gethsemane. I may not be there yet in my journey, but fractally, judgment is always with me in type, presenting itself to me with every decision I face from day to day, moment to moment. Insofar as that’s the case, I seek obedience to match it, at the very least in type. In what ways can I trace the pattern of “Not my will, but Thine be done”?

I don’t think the answer’s to be found amidst the many details at the bottom of the mountain of existence, or in their combination halfway up, but in the view of the whole to be had at the peak. In focusing on communication with others, on serving an audience, on uniting heaven and earth, eternity and time, on attaining the proper lenses — the ultimate objective cannot be lost. And it’s not any of those things. The communion achieved between heaven and earth comes not but from a Source and a Power and a Spirit that is beyond either. The triadic ascent taught by the Fathers is ordered with extreme purpose. Not only is illumination — the perception of God in creation — not to be sought before purification (the practice of the virtues), neither is it to be our final goal. Just as praxis must serve theoria, so theoria must serve a mystagogy beyond illumination. In the perfection that lies beyond illumination, all notion of created things, even God’s energies concerning them, must fall away and be forgotten. Forget all words, all images, all forms, all ideas, and all the lenses used to communicate them. Forget them and let them be forgotten. No attachment to anything sequent to God can be tolerated. Nothing short of the Uncreated Triune Love beyond all speculation and tangibility, can sate the inborn ambition of our heart’s devotion. Heaven and earth may separate and pass away. For the sake of the resurrection that comes afterward, we must let them. For the sake of revealing the God that passes not away, we must wish them not to continue, having faith that the God who remains will yet make them new.

What should I do with my words, I ask myself? I should remember that my destination is beyond all words. My path upwards to that point should fall sufficiently into place if I keep that in mind. It may be easy to lose one’s way climbing down a mountain, but it’s hard to get lost climbing up it.

Boy do I hear you about the difficulties of the "lensing problem." For what it's worth, your writing has been one of the most successful approaches I've seen at encapsulating the fractal and the crystalline in a linear medium.

I don't know what God is calling you to do, Cormac, but I hope you take some comfort in knowing you have touched at least one person's life with your writing and example.

Cormac, thank you for writing. Yours is one of the only Substacks I recommend from my own. I hope that has brought at least one person your way and I hope they have seen what I see in your writing. I too struggle with my purpose in life. Other people probably know my purpose better than I do! At least thats the old world way of looking at it. Reading this has inspired me to keep going with my own struggle, since even in the struggle there can be a connection to others.

I hope to meet one day in person. Also, I know the Iakovos you mentioned. James, he’s good people. May we all meet one day!