Converting desire

It’s the most important thing

I’ve had a strange Lent. The Lord has shown me my lack of desire for Him, but not through any devastating trial or great hardship, nor through any diligent spiritual research, which I haven’t had time to do. A blunt light has been shone on the problem nonetheless. Witness the Gospel reading for St. Mary of Egypt on the Fifth Sunday of Lent, how it begins: “And one of the Pharisees desired him that he would eat with him” (Luke 7:36). The word for “desired” is actually the first word of the sentence: «᾿Ηρώτα δέ τις αὐτὸν τῶν Φαρισαίων ἵνα φάγῃ μετ᾿ αὐτοῦ.» ᾿Ηρώτα — a conjugation of the verb ἐρωτάω. The KJV has “desired”, but the RSV has “asked”; the word in context suggests something in between: to request, to beseech, to “pray” as in supplicate. What ἐρωτάω does not mean is ἔρως (eros). It’s related rather to the simple word for “to say” and despite appearances has no association with love. The sinful woman who shows up weeping with devotion — her sins are forgiven her because she “loved much” (ἠγάπησε πολύ, from the verb agapao). But the Pharisee “loveth little”, despite his supplications for the Lord’s visitation.

So what about me? Do I “desire” that the Lord will come and eat with me? Do I make requests to this effect? Yes, I do. Well, good, Cormac, that ranks you among the Pharisees, congratulations. But when the sinful woman from the city comes to the Pharisee’s house seeking Jesus, when she washes his feet with her tears, dries them with her hair, and anoints them from her alabaster box of ointment, does my behavior match hers? You see, with Pharisaical precision I can tell you the washing away of dirt with tears symbolizes the purification of her soul; the desiccating of moisture with the hairs from her head symbolizes the radiant illumination of her thoughts; and the anointing of feet with ointment from her expensive box of fine, translucent stone symbolizes the perfection of a woman who is offering the cold-pressed oil of all of her desire as a sacrifice to the Lord. But am I doing that? Where is my desire? If I have spent it wantonly as the sinful woman of the city, do I yet bring the fruit of it to the feet of the Lord in broken-hearted repentance?

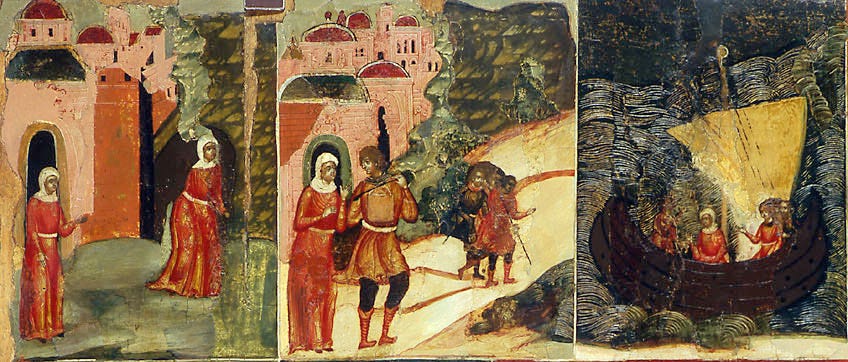

Desires dissipate the soul. If you can imagine, as in a totalitarian country, a mass of faithful Christians gathering to worship in church but police forces dispersing the crowd and preventing the liturgy from happening, this scenario illustrates how desires affect the integrity of the soul and prevent it from realizing the purpose of its existence. Something like this happens to St. Mary of Egypt personally (read her life here) when she is prevented from entering the church in Jerusalem. It happens to me when I stand in prayer yet prefer to wander the realm of my own thoughts — when I have no pain of heart that fixes the mind in that location and keeps it focused on the one prayer to God that can bring wholeness to my being — and I am thus dispersed from the temple of my heart by evil forces. What begins as desire for thoughts, even for good thoughts, can then grow without impediment into desire for deeds.

Such desires fragment families, communities, nations. Consider what we’ve done to music. Music, according to its inner principle, its logos, as revealed especially in the Davidic tradition, is supposed to work unity among people, drawing a plurality of members into a single spiritual harmony based in attraction to the Beautiful. Church music should bring the faithful into a unity of worship. Folk music should gather a nation into a single identity. But — and this perversion occurs at the very introduction of music among the sons of Cain (Gen. 4:21) — we have made music serve the vanity of our sensual pleasure instead. And so everyone in their earbuds can listen to whatever niche of the music industry pleases their broken soul the most. If you try to bond with your neighbor over music, alienation is more likely to occur due to differences in taste. If two lovers find each other who can bond over music, the desire divides them from the rest of society that can’t share their preference. On a larger scale, concerts are held so that those with the same taste can experience an anti-liturgy celebrating in mis-unity the collective fragmentation of their souls through the passion of desire — a faux-ecstasis resembling a serpent consuming itself.

I wrote about it in “Art as food”: of how our lower passions of desire and anger have plunged us in ignorance and delusion, of how, by way of wanton desires and polarized indignation, the forces of evil in this world lead us about by the nose. I lauded Jonathan Pageau for assaulting this widespread ignorance with appeals to logos (reason). I said it wasn’t enough to convert the mind’s reasoning power, but that the lower passions had to be converted as well. It’s plainly not enough to recognize rationally the symbolic triad of the sinful woman washing, drying, and anointing the Lord’s feet; you have to be the woman in the story. You have to desire the Lord as passionately as once you served sin.1 You have to have courage to enter the Pharisee’s house in order to attain your desire. You have to go to church — outwardly, that is. Inwardly, you have to descend into your heart. You have to fall in love. You have to act like it. All my glorious thoughts, my whole alabaster mind palace, earned by fornicating with the world, has to be brought to the Lord’s feet as a sacrifice. With tears. With pain of heart. With courage. With desire.

We get inquirers coming to our church, always a courageous act on their part. But it’s always a man, or if there’s a woman, she’s led there by her man. There are never any independent woman inquirers, or couples led by the woman’s interest. Normally the man has developed an interest in the Orthodox Church from online sources. Judging from what I hear from others, this is a common, widespread phenomenon. Where I live, in my local culture, the name that’s regularly on inquirers’ lips is Jay Dyer. Relative to each other, Jay Dyer is the pugilistic thymos to Jonathan Pageau’s symbolistic epithymia, but as YouTubers they both follow the wider pattern of making masculine appeals to logos, either as truth or as beauty. These men that I meet with their rational aspects turned towards the Church have landed themselves at the outset of repentance, of metanoia, but metanoia refers to a noetic transformation, which for sure entails a rational alteration, but by no means can be limited to it. Just, then, as I have to convert my heart, these men have to convert their women. In order to convert their women, they can’t use the same logical explanations that have motivated them. It’s the same as with me or with anyone else: if these wives and girlfriends are to become the converted hearts their men’s minds wish to rest in, then these men have to learn how to convert their own hearts first. This whole process does not happen easily. It often breaks down at this point. At our church, the pattern I’ve seen (apart from a couple success stories), is that a man will attend services alone a few times, seem really interested, but will manage to bring his wife one Sunday, and we won’t see him again after that. But the struggle is worthwhile. The man who by means of prayer of the heart manages to convert his skeptical wife has won a woman who will lead him soul and body into the inner chambers of God’s grace. Or maybe it’s the case that the lack of a wife’s eventual conversion instigates the pain of heart that the man needs to pray, at last, as he should.

I’ve written about my writings several times before, most recently a couple months ago in the lead-up to Lent, but still I seek the meaning of what it is I’m doing. Creatively, I was most satisfied writing screenplays because it invested all my ideas into stories of full-souled humans in relationships with each other. My intellectual efforts were directed towards the conversion of the lower passions, starting with aesthetic desire. But I had no audience. The readiness for attention is not there. And following the path of converting one’s own desires is not likely to bear much fruit socially when everyone’s desires are so dispersed and fragmented. A musician can write songs that appeal to the desire of others in a style that is desirable to him, but in the current cultural milieu he will thereby lock himself in a secluded niche of aesthetic preference from which he cannot escape. Feelings of alienation and depression will constantly threaten to overwhelm the limited connectivity achieved. In my writing, I turned to where I could find an audience, and, since in the internet age people commonly are looking to coalesce information into knowledge and wisdom, I have written articles appealing more to logos than desire. And hence my desire is left idle and cranky, and we’re back to where we started.

Jonathan Pageau, pivoting away from YouTube to address the same problems I’m discussing, finds popular formats such as the graphic novel and illustrated fairy tales as a way to collect a sufficiently sized audience of desiring souls. My full-throated approval of his projects, alas, can only be academic. I find graphic novels unattractive and have no taste for fairy tales, nor anything related to the fantasy genre, having not been raised on it. I know there are others like me, and I wonder what I can do about it. How can our desire be gathered together and directed towards the unity we all naturally crave? I have this golden opportunity in my life right now to be creatively productive. What should I do with it? My essays operating on the level of Apollonian reason aren’t converting the wives. God help me, I want to meet the needs of women. “A man’s not a man unless he’s providing for a woman.” In my case, as in the case of every individual, the woman here refers anagogically to the heart. I want to convert my heart. Heaven and earth can’t come together to host the Creator of both if the Dionysian appetites aren’t converted to the same cause as Apollonian reason. Vesper Stamper provides good direction in this regard: tell love stories. I want nothing more. But to tell a love story, you have to be in a love story. I have to love Christ, to desire Christ, more than I do.

I wait.... I wait.... The main character of Andrey Tarkovsky’s final film The Sacrifice, Alexander, a retired stage actor of great renown who accomplished all anyone in that profession could have hoped for, yet feels all his life he has been waiting for something, something that hasn’t come yet. Samesies. I mean, I’ve known no success, but that’s just a narrative device Tarkovsky uses so that no one can mistake the kind of things for which we Alexanders are waiting to be any kind of worldly “success”, even artistic success. So... I wait. What can I do but be patient and obedient and pursue sorrow for my sins? Sorrow for my sins. An opportunity to sacrifice something for the sake of something else will come, and I want to be ready for it. But what? And for what? Sorrow for my sins. I refuse to make any assumptions, that I may be ready for anything. But meanwhile, as I spend my time safely, writing articles appealing to Apollonian logos, my Dionysian desires hang flapping in the wind. Sorrow for my sins. As long as I’m resolved not to indulge them dissipatively, I am preserved from dissolution but remain vulnerable to depression, the identification of the mind with eternally unfulfilled desires. Thankfully though, depression is an old enemy that doesn’t work on me like it used to.

I spent my teen years, before entering the Church, horribly depressed. Captive to my desires and constantly punished by them, I saw no way out and embraced the sadness, condemning myself to spiritual paralysis. It was in this condition that the Lord met me and lifted me up. Now, in my new present, that’s what I associate depression with: depression is the place where the Lord finds me and lifts me up. Sorrow for my sins. I actually end up feeling nostalgic for depression but in a humorous way that completely undoes whatever depression might mean in any negative sense. It has been cleansed of paralysis and cowardice in my recollection. The place where that sorrow occurs is the place where resurrection happens, the place where courage is found — where joy sprouts. It’s the place where my love story begins. It’s a remarkable trick that the Lord has played on the spirit of epithymia within me. Whenever my desire lies idle, it sours and turns to sorrow. That sorrow provides a path for me to the pain of heart needed for my repentance, the path that I can follow to the Pharisee’s house, my heart, where my Lord sits with His feet all filthy from His traffic in this world.

By providence the Sunday of St. Mary of Egypt this past weekend featured also the tone five resurrectional service from the Octoechos. And so at Ode Five of the Canon of St. Mary, I chanted,

With the baited hook of the flesh and through the lust of the eyes she took many men prisoner, and by means of short-lived sensual pleasure she made them food for the devil; but now she has herself been taken prisoner, in all truth, by the divine grace of the Holy Cross, and she has been brought as a sweet spiritual offering to Christ.2

Then, that I may know that the life of St. Mary of Egypt is itself the story of Christ’s Resurrection, I found in this prayer to the Lord the same fishing image flipped on its head at Ode Seven, from the Canon of the Resurrection:

Clad in flesh like bait on a hook, by Thy divine power thou didst draw the serpent down, leading up those who cry: Blessed art Thou, O God!3

Amen, amen. So be it, so be it — Blessed art Thou, O God!

Cf. St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent 29.9 (Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 2001), p. 222: “That soul has dispassion which is immersed in the virtues as the passionate are in pleasures.”

Fifth Sunday in Lent, Matins, Second Canon, Ode Five, in The Lenten Triodion, tr. Mother Mary and Metropolitan Kallistos Ware (St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 2002), p. 455.

Sunday Matins, Tone Five, Canon of the Resurrection, Ode Seven, in The Octoechos, Volume III, tr. Isaac E. Lambertsen (The St. John of Kronstadt Press, 1999), p. 16.