How the gifts of the Spirit sometimes appear to conflict within the Church

How political controversies, even heated ones, can occur among saints

The Evangelist Luke makes a strange remark in passing while describing Paul’s journey from Ephesus to Jerusalem in Acts chapter 21. The Apostle Paul has sailed the Mediterranean, landed in Syria, and disembarked at Tyre. He finds disciples in that city and stays with them for seven days. Then it says, in verse 21:4, that these disciples were telling the Apostle Paul, through the Spirit (διὰ τοῦ Πνεύματος), that he should not go up to Jerusalem. It was dangerous for him to go to Jerusalem, so it’s understandable why they would say this — but how could it be said to be “through the Spirit”? This whole journey began back in Ephesus a chapter before when Paul made a big deal about bringing the elders of Ephesus together and explaining how he had to depart for Jerusalem, how he in fact was bound by the Spirit (δεδεμένος τῷ Πνεύματι) to do this (Acts 20:22). How could one and the same Spirit bind the Apostle to an action that through other voices He forbids him from undertaking? Should the Apostle Paul have halted his journey at this point?

St. Maximus the Confessor takes up this apparent contradiction in Question 29 of his Responses to Thalassios (Ad Thalassium). He explains the problem in terms of the diversity of gifts of the Spirit, as when the Prophet Isaiah names seven spirits, by which he means seven activities (energies) of the one and same Holy Spirit. Elsewhere St. Paul uses the words “gifts” to explain these same activities, or energies: “Now there are diversities of gifts, but the same Spirit” (1 Cor. 12:4). Hence, St. Maximus explains:

If, then, the manifestation of the Spirit is given according to the measure of each person’s faith, it follows that each of the faithful, through participation in such a gift, receives a measure of grace “according to the proportion of his faith” (Rom. 12:6) and to the underlying disposition of his soul, a grace which endows him with a fitting state of mind adapted to the activity required to realize this or that commandment.

Thus, just as one person receives the principle of wisdom, another of knowledge, another of faith, and another some other gift of the Spirit enumerated by the great Apostle (cf. 1 Cor. 12:8–11), so too does another person receive, through the Spirit, the gift of perfect and immediate love for God, containing nothing material, according to the due proportion of his faith. Another person, through the same Spirit, receives the gift of perfect love for his neighbor, because, as I said, while each one possesses a gift that is proper to him, it is activated by the same Spirit. Now if someone, following the holy Isaiah, were to call these gifts “spirits,” he would not miss the mark of truth, for the Holy Spirit exists in every gift, be it great or small, being actively present in proportion to it.

Thus when the truly great Paul, being the servant of mysteries transcending the human mind, directly received in proportion to his faith the spirit of perfect grace in the love of God, he disobeyed those who had received the gift of perfect love for him. For those men, being “inspired by the Spirit” — that is, by the spiritual gift of love for Paul, which was actualized within them, for their sake, by the Spirit (for “spirit” is the same as “gift,” as I said a moment ago, in reference to the passage by the prophet Isaiah) — “told him not to go up to Jerusalem.” But Paul disobeyed them because he regarded the love which is divine and beyond understanding as incomparably superior to the spiritual love which the others had for him. And indeed he did not go up “disobeying” them at all, but rather by his own example he drew them — who prophesied through the activity of the Spirit measured out in due proportion to them according to the gift of grace — towards that yearning desire for the One who is beyond all. In this way, the great Paul did not disobey the Spirit, but rather he taught those who were prophesying about him, according to their gift of love, to ascend from the lower to the higher spirit, that is, from the lower to the higher gift.

And, again, inasmuch as the prophetic gift is greatly inferior to the apostolic gift, it was not appropriate to the Word — who governs the universe and assigns each one his due rank — that the superior should submit to the inferior, but rather that the inferior follow after the superior.1

The Christians at Tyre, in their love for Paul, activated by the Spirit, did not want to see Paul suffer. Paul’s superior gift of divine love spurred him on regardless of suffering, and in this he was more Christ-like. All these things are true: Christ, out of love for us, does not want to see us suffer; Christ, again out of love, is willing to suffer for us; Christ, once again out of love, wants us to be like Him, willing to suffer out of love. The Tyrians’ love for Paul is activated by the Holy Spirit neither so as to halt Paul from his superior journey, nor to no purpose, but to reveal the suffering Paul is willing to endure out of a superior apostolic love for God and man. And the whole apparent conflict is arranged so as to draw the Tyrian Christians up from their inferior love, into this superior love.

It’s just like the traditional method of painting icons: on darker colors are laid down ever lighter and lighter colors not so as to create contrast as with chiaroscuro, but to arrange a hierarchical ascent allowing the whole image to participate harmoniously in one and the same light, each shade according to the degree it is able. This is how the Church teaches us to understand apparent contradictions in Scripture — and, among the community of the faithful, how to understand the appearance of conflict within the grace of the Spirit: not dialectically, but hierarchically. There is a hierarchy of gifts that we are called to climb within our lives in this age, ever increasing in Christ-like humility, ever gaining in virtue.

We can think of it in terms of this Venn diagram, if the big blue circle delineates all the grace of the Spirit in this world:

Someone, the red circle, might have one portion of grace, and another, the yellow circle, might have another. They don’t overlap and so might appear to contradict, but they are equally contained within the activity of the one Holy Spirit. The red one, being superior, should understand that and recognize the gift of the Spirit within the yellow one, showing no contempt for its inferiority. But then, the red one could stand to become bigger, couldn’t it? Maybe learning to recognize the yellow one’s grace and cherishing its existence is precisely what it needs to do to expand in grace. This idea of expansion is referenced when the Psalmist prays to the Lord, “The way of Thy commandments have I run, when Thou didst enlarge my heart” (Ps. 118:32 LXX).

Not all “spirits” are contained within the activity of the Holy Spirit, though, we must also recognize. If you can’t see where the Spirit is and where He isn’t, if that’s not one of your charisms — which is the default condition in this fallen world — it can get confusing:

What about that gray circle, right? Without our blue Holy Spirit glasses, we can’t tell the difference between him and the other circles. He’s bigger than the yellow circle, and that’s impressive. He’s closer in proximity. Even the red circle could be deceived. But if the red circle expands to encompass the gray circle, it will be exiting the grace of the invisible Spirit. Learning discernment of the spirits hence is part of the growing experience.

But let me get less abstract and talk about some historical examples. The Church has plenty experience rejecting the gray circles: the Nicolaitians (Rev. 2:6, 15), the Simoniacs (cf. Acts 8), that unfortunate Corinthian man who thought it within the bounds of respectability to fornicate with his father’s wife (1 Cor. 5) — et cetera, all throughout history. Such cases, of course, are essential to discern, but I’m interested here in naming some of the apparent instances of conflict of spirits within the Body of the Church.

The prime example, of course, is Sts. Peter and Paul. Paul finds cause to tell the Galatians via epistle of how at Antioch he “withstood [Peter] to the face, because he stood condemned,” explaining, “for before that certain came from James,” that is, from Jerusalem, “he did eat with the Gentiles: but when they were come, he withdrew and separated himself, fearing them which were of the circumcision” (Gal. 2:11–12). Though his behavior appears changeable, Peter was at no point in this affair ignorant as to what should be done in principle. He had already experienced the vision of the sheet with all the clean and unclean animals and how the Pentecostal gift of the Holy Spirit came down on the Italian centurion Cornelius and his Gentile companions, even before holy baptism (see Acts 10). He knew it was according to God’s good pleasure for him to eat in communion with Gentile Christian believers who did not observe the letter of Moses’s law. The Judean Christians from Jerusalem, however, who did of course still observe the letter of Moses’s law, yet lacked this revelation and would have been scandalized to see their apostolic leader eating in communion with the uncircumcised. Peter “feared them,” as Paul puts it, which is to say, out of love he could not bear to offend them. Peter loved them no less than the Gentile Christians of Antioch, and this is a gift activated in him by the Holy Spirit. What’s to be done? How do you bridge this gap in charisms?

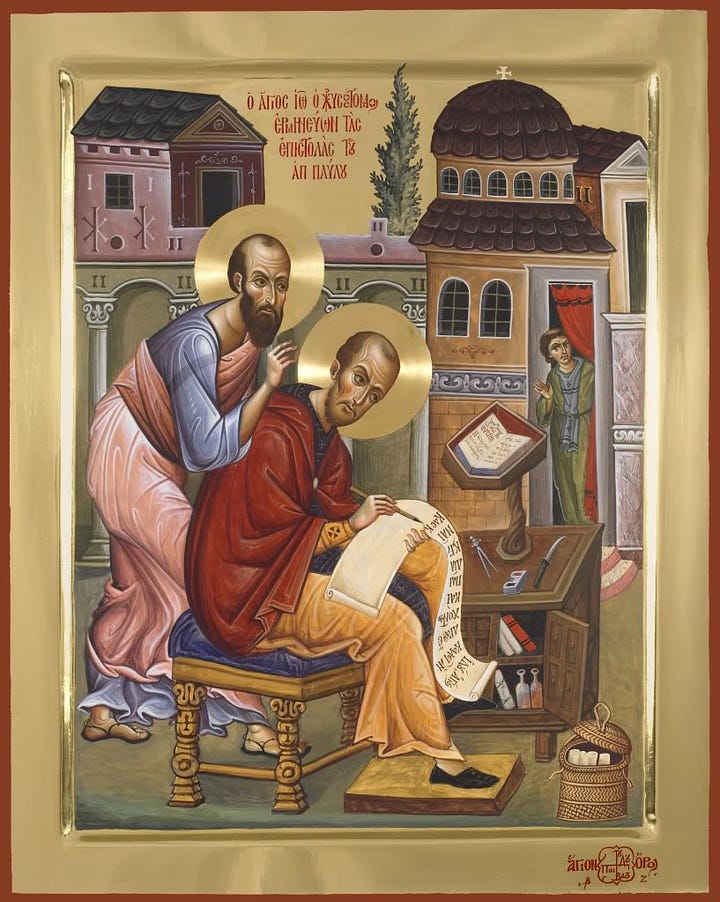

St. John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople, among whose spiritual gifts is the proper interpretation of the Pauline letters — whose skull, preserved at Vatopedi Monastery on Mt. Athos, features an incorrupt ear on account of St. Paul having whispered in it — explains the whole confrontation at Antioch to be a pious ruse, arranged for the benefit of the faithful, to bridge the gap of their charisms and raise them to a superior love. He comments,

The Apostles, as I said before, permitted circumcision at Jerusalem, an abrupt severance from the law not being practicable; but when they come to Antioch, they no longer continued this observance, but lived indiscriminately with the believing Gentiles which thing Peter also was at that time doing. But when some came from Jerusalem who had heard the doctrine he delivered there, he no longer did so fearing to perplex them, but he changed his course, with two objects secretly in view, both to avoid offending those Jews, and to give Paul a reasonable pretext for rebuking him. For had he, having allowed circumcision when preaching at Jerusalem, changed his course at Antioch, his conduct would have appeared to those Jews to proceed from fear of Paul, and his disciples would have condemned his excess of pliancy. And this would have created no small offence; but in Paul, who was well acquainted with all the facts, his withdrawal would have raised no such suspicion, as knowing the intention with which he acted. Wherefore Paul rebukes, and Peter submits, that when the master is blamed, yet keeps silence, the disciples may more readily come over. Without this occurrence Paul’s exhortation would have had little effect, but the occasion hereby afforded of delivering a severe reproof, impressed Peter’s disciples with a more lively fear. Had Peter disputed Paul’s sentence, he might justly have been blamed as upsetting the plan, but now that the one reproves and the other keeps silence, the Jewish party are filled with serious alarm; and this is why he used Peter so severely. Observe too Paul’s careful choice of expressions, whereby he points out to the discerning, that he uses them in pursuance of the plan, (οἰκονομίας) and not from anger.

His words are, “When Cephas came to Antioch, I resisted him to the face, because he stood condemned;” that is, not by me but by others; had he himself condemned him, he would not have shrunk from saying so. And the words, “I resisted him to the face,” imply a scheme for had their discussion been real, they would not have rebuked each other in the presence of the disciples, for it would have been a great stumblingblock to them. But now this apparent contest was much to their advantage; as Paul had yielded to the Apostles at Jerusalem [as when he submitted to the council led by James in Acts 15], so in turn they yield to him at Antioch.2

The Greek word for face here, πρόσωπον (prosopon), means face, but it also means person, as in the Latin sense of persona; it refers to one’s social role and public reputation. So, for example, when Scripture says God is no respecter of persons (Acts 10:34, Rom. 2:11), it means He disregards social status and how one is esteemed among men, having His own standards of judgment. For Paul to withstand Peter to his prosopon means to confront him in the capacity of a public figure. This Peter skillfully invites with his behavior, using his public image — willing even to sacrifice his public honor — so as to benefit those less gifted than he and draw them up into a superior love, inspiring them, moreover, with a staggering display of courage and humility. Paul knows the score and plays his part. These apostolic leaders are sailing an ocean of subtext in this scene as they navigate the straits between the Old and New Covenants, a miraculous maneuver made possible only by the hand of the Holy Spirit. Such an act of love and humility is the kind of cardiac expansion necessary to bring non-overlapping circles together in the hierarchical unity of the Holy Spirit.

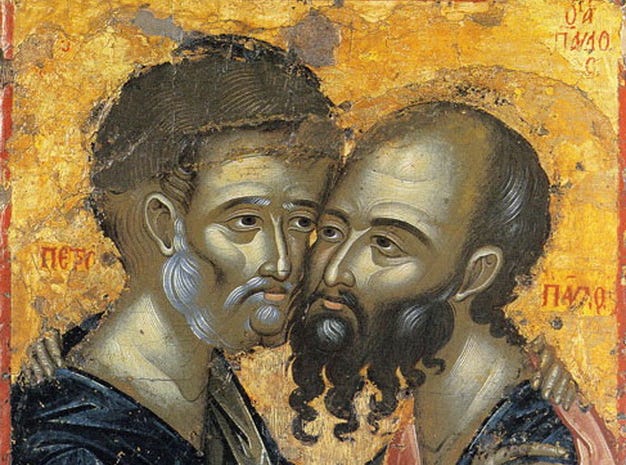

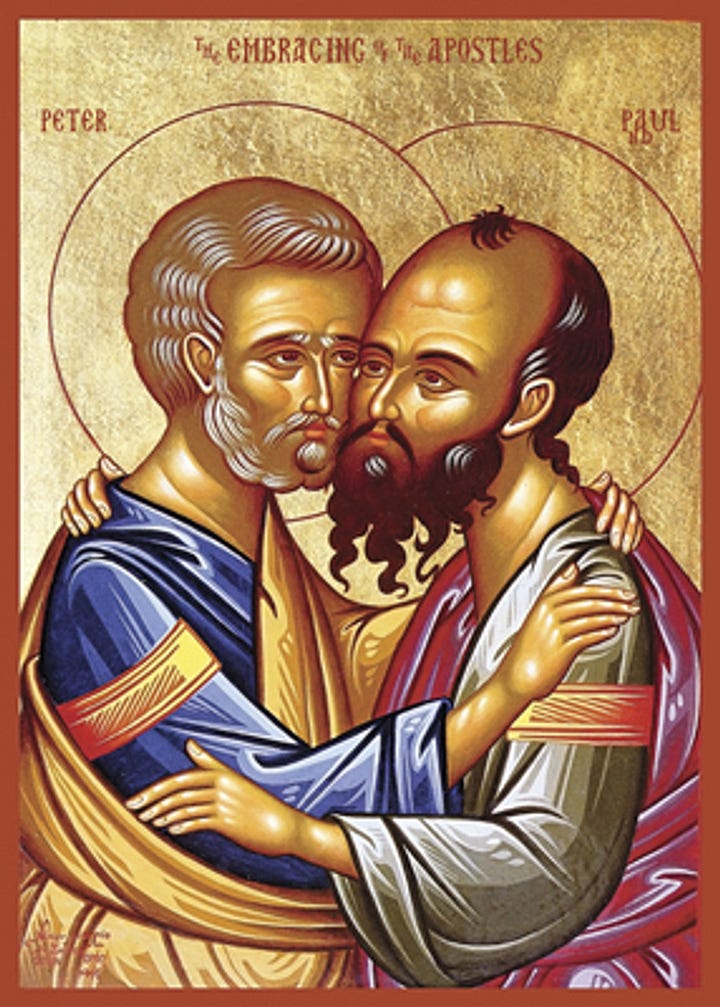

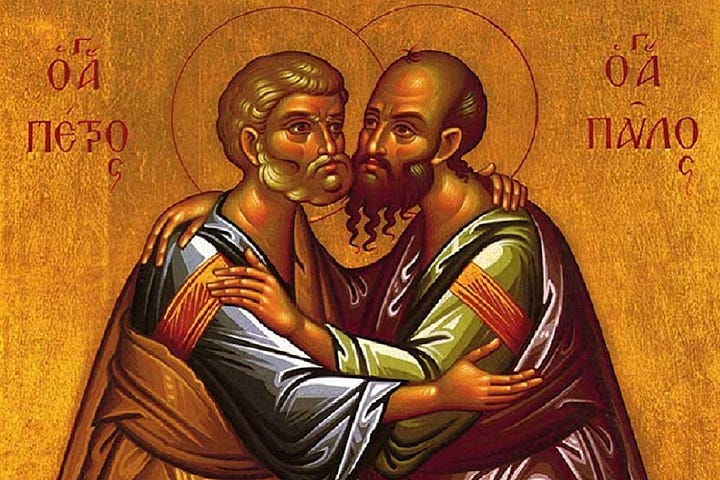

That’s the prime example. It’s the kind of resolution of conflict that inspires infinite awe and appreciation — Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God (Matt. 5:9). Hence on the Church calendar we celebrate Sts. Peter and Paul, the Apostle to the circumcision and the Apostle to the nations, not separately but together on one feast day, June 29th. At Antioch, the Apostle to the nations may have appeared publicly to have the superior gift, but subtextually, the sacrificial gift activated in the Apostle to the circumcision demonstrates the justification for his spiritual primacy, as far as the hierarchy of gifts is concerned. It’s interesting, in most icons I’ve seen of these two apostles embracing, as their circular halos overlap, that of St. Peter stays in the foreground, as St. Paul’s recedes behind it.

As Church history proceeds, as down a mountain, problems arise reconciling more complex, more particular identities. Two controversies come to mind that I would especially like to discuss if briefly, two occasions when a fierce disagreement came to a head in the Church, but in both cases the leaders of the opposite camps are both recognized as saints.

The first took place in seventh-century Britain; St. Bede writes about it in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Anglo-Saxons had migrated to Britain from continental Europe beginning in 449. These Germanic pagans naturally had much acrimony with the native Celtic Britons who were Christian. Change began to occur in 595 when St. Gregory the Great, Pope of Rome (known in the East as the Dialogist for the Dialogues he wrote) sent a monk named Augustine to Canterbury to missionize the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Kent. The house of King Ethelbert of Kent was converted and St. Augustine was made bishop in 597.

In the northernmost parts of what we now know as England, meanwhile, St. Aidan in 635 came down from the Irish monastery of Iona in the Scottish Hebrides and founded a new monastery on Lindisfarne, a tidal island off the northeast coast of Northumbria. From this monastery the Christian faith spread rapidly in the north, but its traditions and customs — with which practices the faith was very tightly identified, so embodied and ritualistic were these peoples (characteristics only encouraged by the religion of the Incarnate God) — contrasted sharply with the Roman traditions imported through Canterbury. There were no dogmatic differences, but the Irish church had its own liturgical calendar, not following standardizations that occurred in the Roman church the previous century for things like the calculation of Pascha. And countless other visible symbols differentiated the two traditions and embodied a division between the peoples.

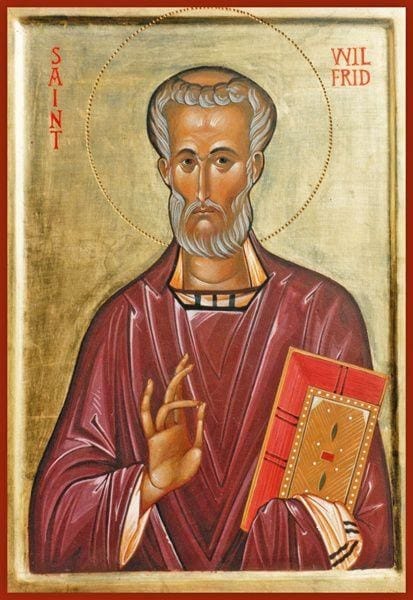

This division grew more and more disruptive the more Christian the Anglo-Saxons became, which, once it began, was a rapid, top-down, royal-led process. Eventually King Oswy of Northumbria called a council at St. Hilda’s monastery at Whitby in 664 to settle the controversy and declare a unity of religious practice. The two most prominent points of contrast were the calculation of Pascha and the style of monastic tonsure, a very visible symbol of group affiliation. St. Colman, abbot of Lindisfarne, third in line after St. Aidan, led the arguments on behalf of Irish customs. St. Wilfred, abbot of Ripon monastery, a Northumbrian monastic trained partly at Lindisfarne, but who had traveled widely in Western Europe including recently in Rome, spoke on behalf of unity with the continental church.

The objective of the council was to establish Pentecostal unity. The apostolic Church is one, containing the pluralities of human expression, as experienced at Pentecost, but not at the expense of unity. As those Apostles spread out from Jerusalem, different liturgical customs were developed in different regions, a natural process whereby the Gospel became incarnate in different peoples. The Irish traced their tradition to the Johannine community at Ephesus, claims of apostolic legitimacy not contested by the adherents of Roman practice among the Anglo-Saxons. But St. Wilfred and his party argued that the Petrine authority of the Roman church was a superior charism to which the Anglo-Saxon adherents of the Irish traditions should yield.

That’s the line that carried the day at Whitby, and I can see historically how this decision was the right one. We follow the traditions of our fathers in order to maintain unity with them and not trail off into apostasy of our own making. But the Church exists not only in the past but also in the present and in the future. So as not to break off from the Body of Christ we must also attend to unity with present brothers. More than that, we must strive to hand down to our children and grandchildren the practices of the Church that they will need to meet their historical moment and not fall away from Christ. While adherence to religious forms of the past is the basic mode by which the eternal principles of Christian living are transmitted, the Gospels we read in the Bible are all about those who carry out this adherence in the wrong way, betraying their Creator and Savior in the process. A deeper mode of Spirit-filled creativity is necessary to leaven the traditional practices of the past.

The Irish church had survived on its own to this point in time beyond the edge of civilization based on a splendiferous burst of monastic energy, an energy which, whenever and wherever it has been observed in history, always has an expiration date. When it expires, renewal is needed from elsewhere in the Church, another apostolic branch. The Irish were busy at this time providing just such renewal for the Germanic peoples of Europe whose faith was stale (and whose conversion arguably was from the beginning on shaky grounds), by means of the missions of Sts. Columbanus, Gall, Fiacre, and many others. But the clock was ticking for the Irish, and the time would soon come when their continuance in the Body of Christ would depend on their unity with the rest of the Church. It was an eminently good thing for them, humbly and amidst great adversity, to adhere to the ways of their fathers, a charism activated by the Spirit and embodied by St. Colman of Lindisfarne. But St. Wilfred, by going outside of himself and his culture, going on pilgrimage and expanding his heart in submission to a larger view of the Church, embodied a superior charism and better saw the future needs of the churches in the British isles.

St. Colman may have lost the Council of Whitby, and thereby his position as abbot of Lindisfarne, but we do not hold his charism in contempt; rather we cherish it, and call him saint. Upholding the gift of the Spirit entrusted to him, he retreated first to Iona in the Hebrides where he could continue the ways of his Irish forebears, and then to the island of Inishbofin off the west coast of Ireland where he founded a monastery for his disciples, half of whom were Irish and half were Anglo-Saxon adherents to the Irish tradition. As the years moved on, however, the cultural differences between the two sides caused a rift that the unity of their religious opinions could not contain. St. Colman had to move the Anglo-Saxon monks off Inishbofin and onto the mainland where he founded a new separate monastery for them — a tacit admission that, for unity’s sake, he should not have prevailed at Whitby.

But St. Wilfred’s victory was not without downsides of its own. The potential for peril was present in his position as well — signified by ominous portents in the year of the Council of Whitby, 664: a total solar eclipse seen in the British Isles that spring preceded a terrible and deadly plague, the first of its kind in the recorded history of Britain, which, like Roman influence on the Anglo-Saxon church, started in the south of England and moved northward. St. Wilfred’s reliance on Petrine authority was packaged with reliance on royal patronage, the pattern first established by St. Augustine’s mission to Kent at Canterbury. In one sense, the larger sense, this was the right decision. Under Roman customs, Lindisfarne Monastery would soon have as its leader St. Cuthbert, its greatest, most Spirit-filled saint and a shining light of unity for all of Britain. But — and St. Wilfred would learn this firsthand — what happens when royal patronage turns sour? What happens when the archbishop of Canterbury (namely St. Theodore of Tarsus, a light of Syrian Orthodoxy for nascent Christian England) presumes jurisdictional control over your diocese and does many things against your will? The whims of kings and quarrels with saints would cause St. Wilfred continual trials and woes. Consecrated bishop for Northumbria in Gaul directly after the Council of Whitby, he was obstructed from being installed for four years by a king who placed an irregularly made bishop in the position instead. Then ten years later, a king expelled him, and St. Theodore teamed with St. Hilda to counter St. Wilfred’s influence in the north.

This story is way too complex to recount here, as reliance on present human authority from above, be it royal or episcopal, is no simple solution to ecclesiastical challenges in this world. St. Wilfred would be exiled and re-exiled, at one point ex-communicated (wrongfully, of course), making continual journeys to Rome to appeal his situation, not always to his satisfaction. You live by authority, you die by authority. I can tell from the convoluted story of St. Wilfred’s life that, while God approved of his appeal to the present authority of the Church at the Council of Whitby, He yet made sure that St. Wilfred knew that as a servant of Christ the King he could have no home in this present world.

Speaking of monastic flowerings reaching their expiration date, I have one more instance of dueling saints to mention. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as the Constantinopolitan Empire diminished and fell, a rush of hesychastic activity poured into Muscovite Russia. Such deeply Christian hermits populated the virgin northern forests, attracting such large flocks of disciples, that the similarity to fourth-century Egypt earned the movement the nickname “The Northern Thebaid.” As always happens, however (as, indeed, it happened in Egypt), the monasteries became institutionalized, the animating spirit of the movement could not be maintained, and the situation required some kind of renewal or change.

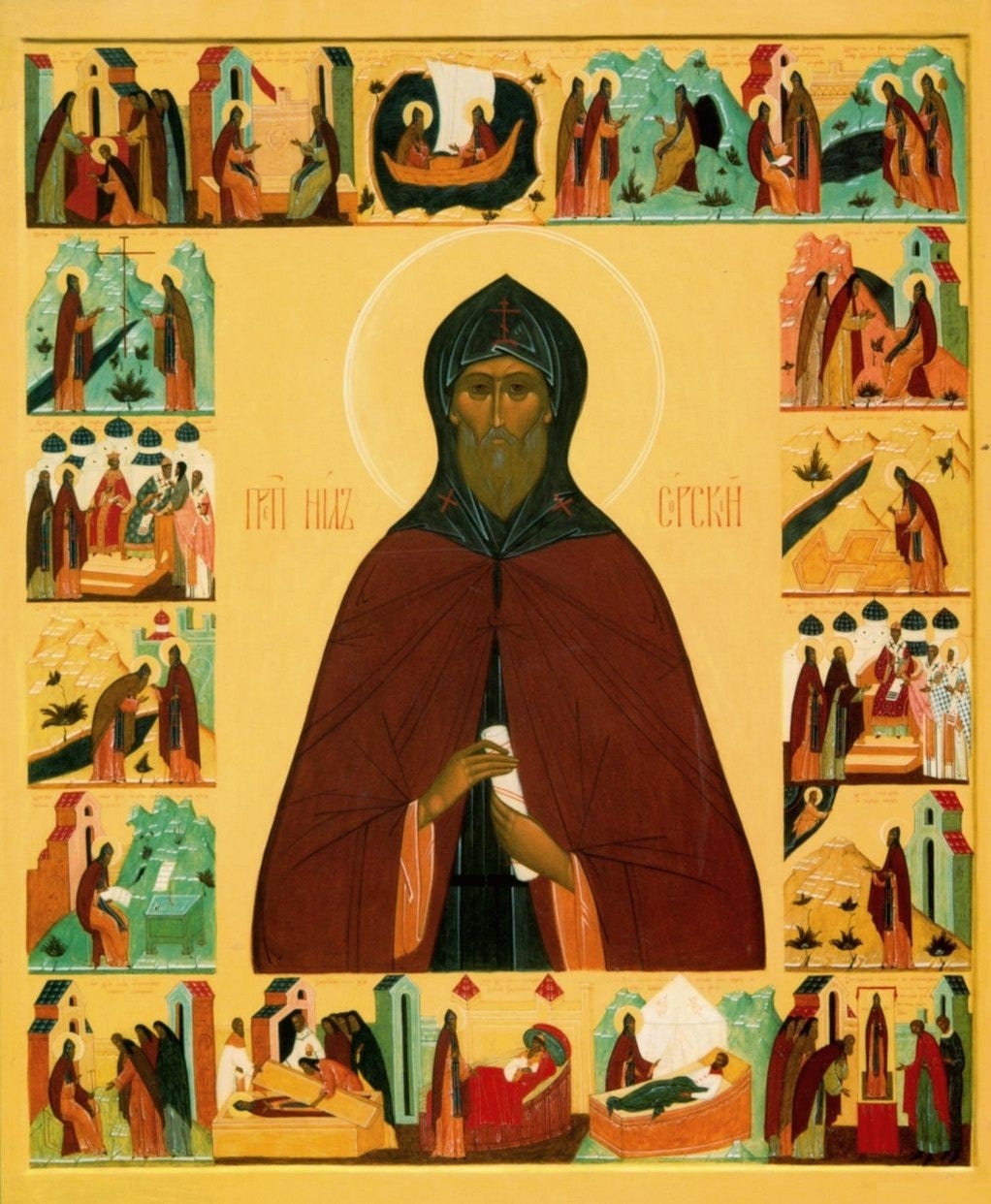

St. Nil Sorsky (†1508; see icon above), whose name is Romanized as St. Nilus of Sora, went the pilgrimage route for renewal. Leaving White Lake Monastery — the spiritual life of which had deflated since the death of its founder, the great St. Cyril — St. Nilus went abroad to the Holy Land and the Greek territories then ruled over by the Ottoman Turks. In Constantinople and especially Mount Athos, he found holy monks and holy monastic writings that afforded him access to the inner life of the Church. After several years abroad he returned to the Northern Thebaid and founded a skete a short way from White Lake Monastery. Skete living, as St. Nilus learned on Mt. Athos, represents the middle way for monastics, allowing a small collection of monks to live a short distance from each other, being neither strict hermits living all alone nor members of a large barracks-style monastery known as a coenobium.

St. Joseph of Volotsk (†1515) was an ardent proponent of the coenobitic life and fervently strove to elevate the spiritual quality thereof. Whereas St. Nilus lived north of the River Volga far from centers of power, St. Joseph was part of the ring of monasteries in the region of Moscow which had originally been founded by St. Sergius of Radonezh with the heights of monastic achievement to his credit, but since then had become more worldly and aligned with tsarist power. The contemplative and active aspects of monastic life — two gifts of the Spirit undoubtedly meant to go together — were becoming bifurcated by the Volga both geographically and politically.

The two movements came to a clash at a council held in Moscow in 1503, primarily over the issue of monastic landownership. At stake was whether monasteries should own the villages that formed around them or not. This legal matter stood in for the argument of what the purpose of monasticism should be, to serve God or to serve man. These two commandments, requiring different gifts of the Spirit to fulfill, should both be fostered in a hierarchical relationship, but the fallen world always puts them in conflict with each other. St. Nilus, ever pursuing the “one thing needful” (Luke 10:42), represented the superior side, dubbed the Non-possessors, and St. Joseph represented those called the Possessors. St. Joseph’s idea of the monastic life entailed strict coenobitic obedience to a single leader, and that pattern of governance aligned him with the tsarist amalgamation of power and in general put church leaders in such a position that prioritized their service of others. His side won out, and not, I don’t think, without good purpose, despite St. Nilus representing the superior charism. The monastic styles of the coenobium, the skete, and the solitary life of the hermit outwardly represent the three ascending stages of the spiritual life, purification, illumination, and perfection. The spiritual condition of the Russian people was such that the coenobitic patterns of purification were necessary to emphasize for their collective forward spiritual progress.

But neither style of Christian life can survive without the other, and already their bifurcation was a sign of spiritual decline from the era of Sts. Sergius of Radonezh (south of the Volga) and Cyril of White Lake (north of the Volga) when they went together harmoniously in both cases. Russia’s long march towards annihilating itself in the twentieth century can be seen to grow out of this division of Non-possessors and Possessors, as historian Ivan M. Kontzevich summarizes in his introduction to the collection of saints’ Lives The Northern Thebaid.3 The Possessors cut themselves off from the source of spiritual discernment and easily fell prey to wicked leaders (the gray circles, as in my Venn diagram above). For survival, they stressed rigid adherence to the outward forms of ritual in such a way that required the disaster of the Old Believer Schism in the seventeeth century to force a religious reset — a reset which itself led to the catastrophic Westernizing reforms of Peter the Great in the early eighteenth century. The contemplative aspect of the spiritual life, meanwhile, divorced from the laity and retreating into itself in the generations after St. Nilus, became more and more reliant on personal ascetic struggle to attain the spiritual heights of earlier fathers. I refer to extreme behaviors: wearing iron helmets and iron chains and performing various labors of mortification, which might bear fruit for an increasingly limited few but is by no means socially sustainable. This path does not provide for future generations, and indeed the spiritual life in Russia dropped to extremely low levels in the succeeding centuries before a hesychastic rebirth was seeded from abroad in the eighteenth century.

Nevertheless, none of these larger historical movements, in their downward trajectory, are attributable to the lives of the saints. Ever models for emulation, saints like Nilus of Sora and Joseph of Volotsk dealt favorably with the charisms they were given, bucked the trends of sin, and prolonged the life of their nation by shining the light of God to those around them. They did this even while arguing against each other on opposing sides of a council! The political division that they could not but participate in is not attributed to them. It should be a great comfort to us Christians in these last days, when we are so conscious of all the downward historical trajectories whizzing and exploding all around us like missiles, to know that fixing any of these trajectories is not our responsibility. Following the commandments of the Lord — according to the contemplative, theological patterns visible within them, knowledge of which is handed down to us by our fathers, along with reliable, practical methods for instantiating these patterns — need be our only focus. There is a charism, a gift of grace, that is offered to each of us, according to the proportion God knows we are capable of fulfilling. Will we accept our calling? Will we resist our passionate urges of desire and control on a daily, moment-to-moment basis? Will our every breath praise the Lord? Will we let this charism of praise raise us above our differences within the grace of the Spirit and unite us in Pentecostal unity?

St. Maximos the Confessor, Ad Thalassium 29.2–5, in On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios, td. by Fr. Maximos Constas (The Catholic University of America Press, 2018), pp. 196–98.

St. John Chrysostom, Commentary on Galatians 2:11–12, td. anonymously, revised by Gross Alexander, from Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 13, ed. by Philip Schaff (Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1889), pp. 18–19.

See The Northern Thebaid, compiled and td. by Fr. Seraphim (Rose) and Fr. Herman (Podmoshensky), third edition (St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2004), pp. 10–14.

I find the description of the confrontation between Peter and Paul quite enlightening. As a Protestant (for 35 years) I'd always believed it was a genuine disagreement (and perhaps a dig at all things Petrine). Since becoming Orthodox I'd only ever heard one-liners about it - "Yeah, it was a ruse, a setup". But, I think I'm understanding it now. In fact we probably see it all the time. A wise school teacher may observe a "leader" (lets call him Jack) amongst the students being pressured by their "followers" to commit an infraction or advance a dubious agenda - leaving the school grounds at lunch-time perhaps. If the teacher, addressing Jack in front of the entire class says "And Jack, I don't want to hear anymore about you and your friends leaving the grounds at lunch-time" the pressure from below is released. Jack is simultaneously, rebuked, freed and validated as an informal leader. The hierarchy is strengthened.