Leviticus as a triadic fractal patterned after the Tabernacle

The chiastic center of the Pentateuch transforms the chiastic model

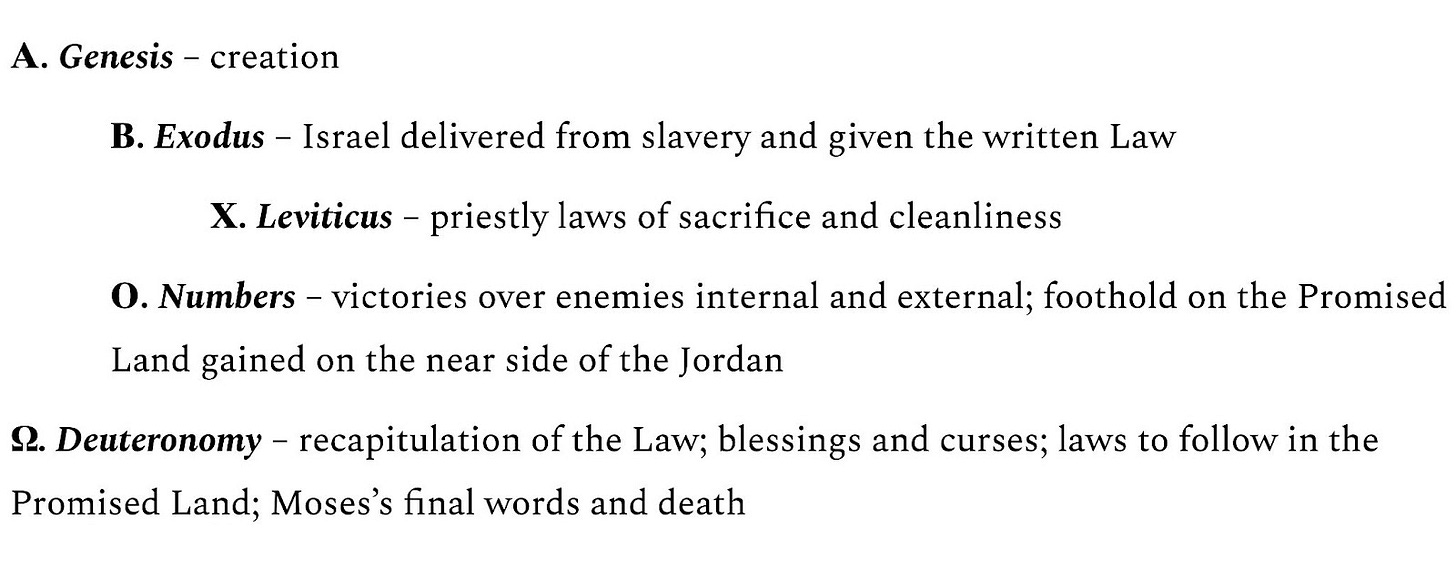

Leviticus, the third Book of Moses — a symbolic guidebook for how to approach God — stands at the center of the Pentateuch. I’ll remind the reader what this primary example of the cosmic chiasmus looks like:

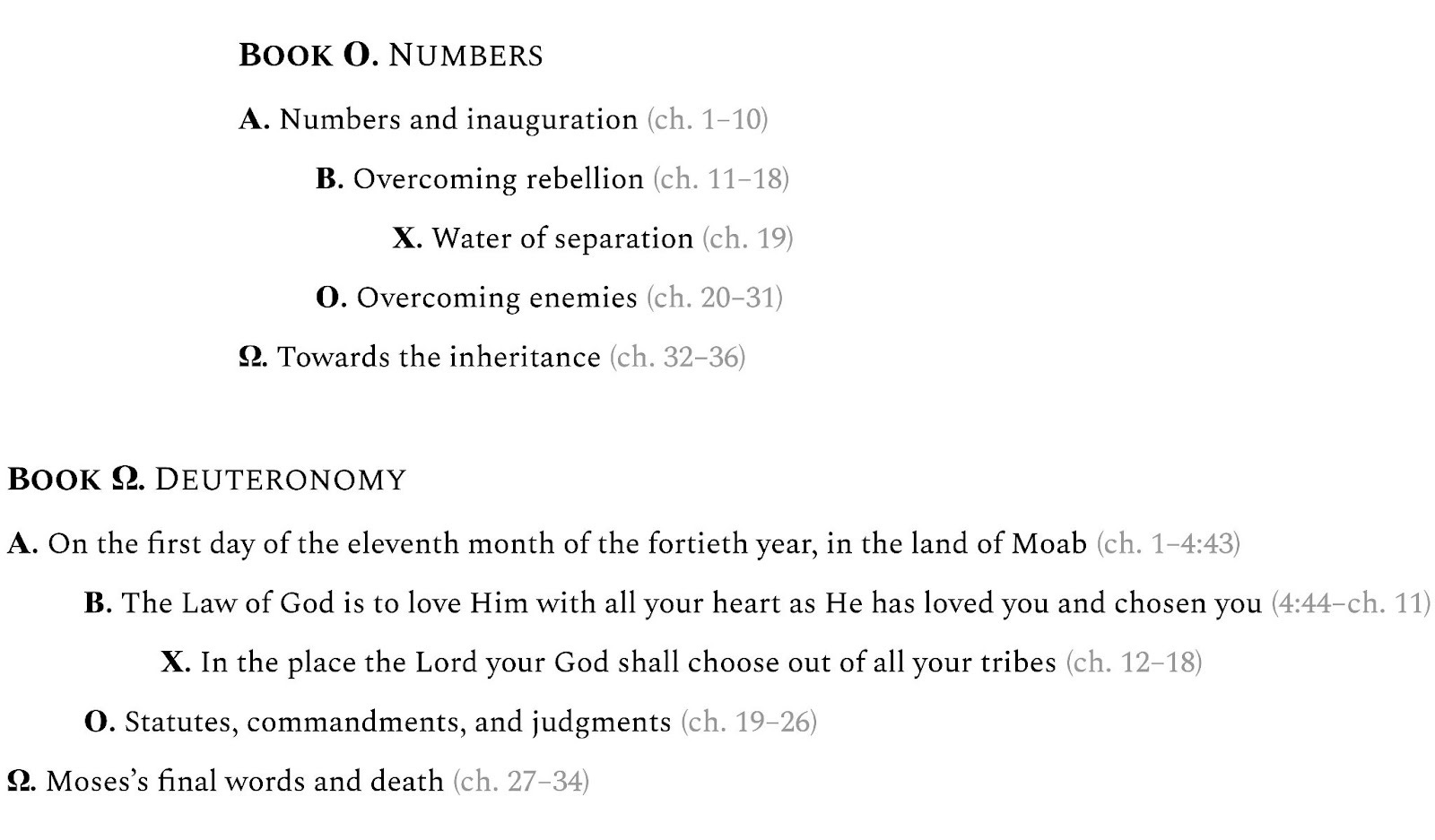

And of course, fractal-wise, this pentadic pattern repeats within the individual books. We’ve seen (in “The Cosmic Chiasmus”) the fivefold structures of Genesis and Exodus. For reference, I include their summary at the bottom of this article‚ but here, quickly, are the basic outlines of Numbers and Deuteronomy:

The water of separation at the center of Numbers prefigures the waters of baptism used by the Church as its boundary and threshold. It is sanctified by ashes from the red heifer (that is, in type, the crucified body of Christ), which is sacrificed outside the camp, just like Moses had to do with his tabernacle of testimony (in Ex. 33) — because this is what Christ has to do on the Cross outside Jerusalem. This holy water is used to purify those who have had contact with death. Those immersed in the baptismal font of the Church have put on the Christ who overcomes death.

Deuteronomy, for its part, is centered around the land and prophet to be provided to the people of Israel by their God. The land is the promised land, which is to say, typologically, it is the kingdom of heaven prepared for the Lord’s holy ones in the end of days; there God will choose a place for His Name, where alone the Israelites will bring their sacrifices. To this end, besides the kings and priests, the Lord will raise up a Prophet (the Messiah) both like unto Himself (18:15) and like unto Israel, being from among their brethren (18:18), to mediate between Israel and God, as does Moses. This Prophet is to be discerned from all the false ones.

Again, heavy Christological passages dot the chiastic centers of these books, even as Leviticus marks the middle of the Pentateuch due to its focus on priestly sacrifice, the mediation of death and life, and atonement for sin. But what about the interior structure of this central book?

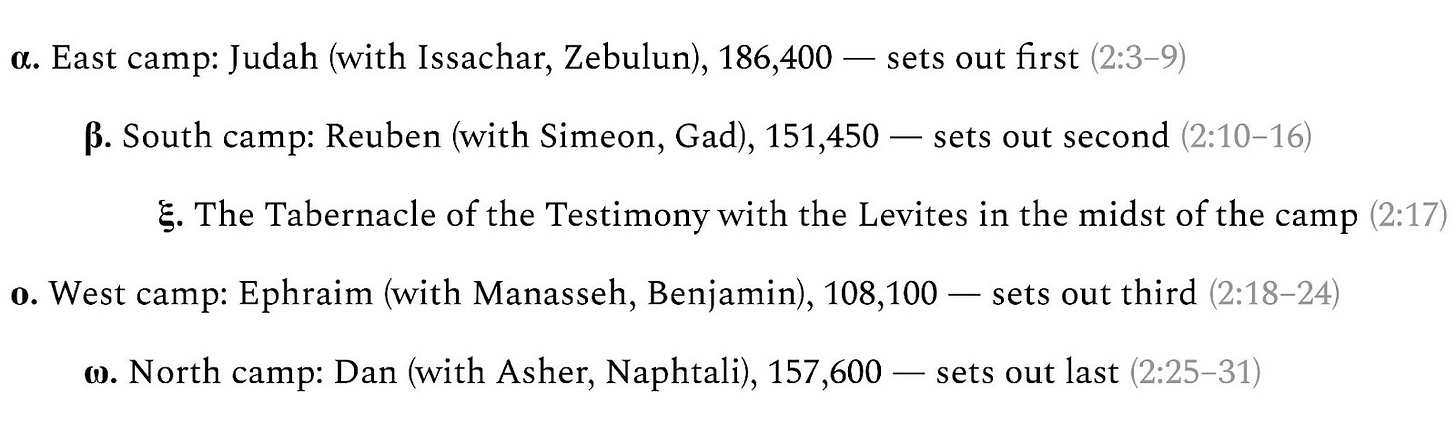

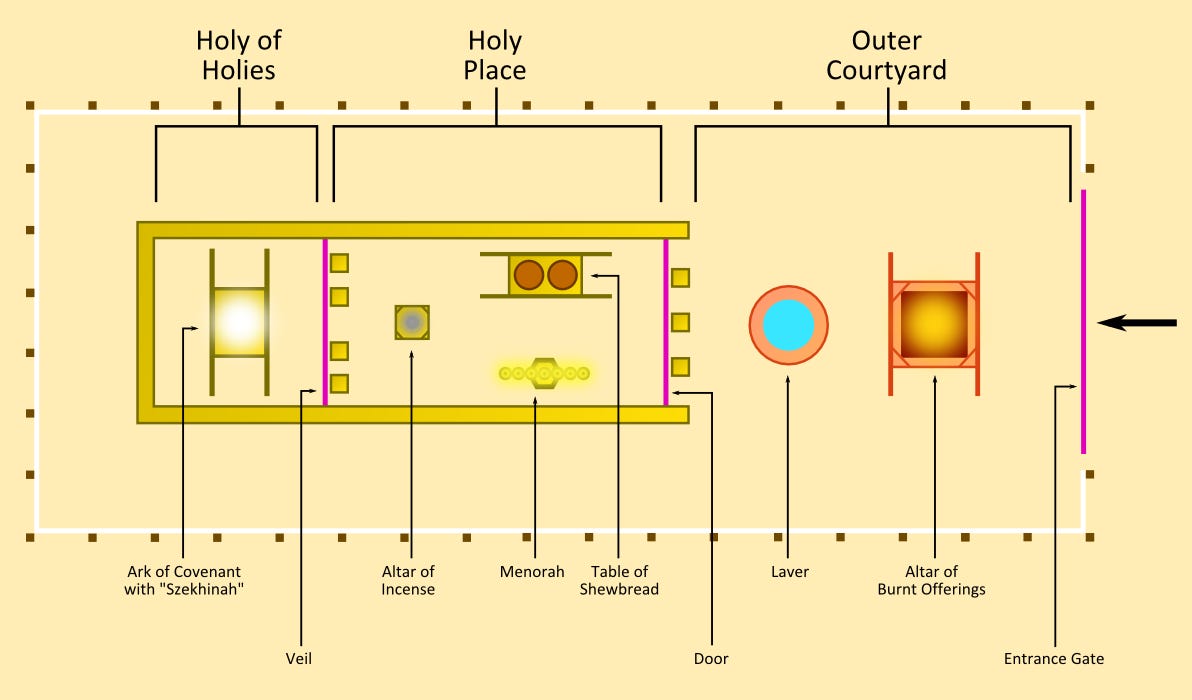

A dutiful student of Leviticus, peering into its symbols and seeking to discern the shape of their sequence, will struggle to see how the book could possibly conform to a chiastic structure. (It’s been tried, with unsatisfying results.1) And why should it have to? As the central summit of the Pentateuch, Leviticus is freed from the exigencies of symmetry and can apply itself to expressing the means of a relationship (between God and man) which is completely the opposite of symmetrical. And remember also the ksiastic shape of Israel’s camps as they journeyed through the wilderness, from Numbers 2:

That’s the Tabernacle in the middle. It’s not like the other camps either in physical arrangement or in literary structure. It is set apart as holy and serves as the very source of holiness; it contains the place, between the cherubim above the ark, from whence God makes Himself known to His people. This is where man approaches God, and as we learned in Exodus, the place is shaped according to a pattern of triadic linear ascent (see previous article). At the end of Exodus, however, merely the second Book of Moses, the Lord’s glory covers the Tabernacle in a cloud such that Moses is unable to enter (Ex. 40:34–35). According to the literary sequence, further typological mediation is required, and that’s the role the third and central Book of Moses serves. Leviticus is not chiastic in its overall shape, but triadic and linear.

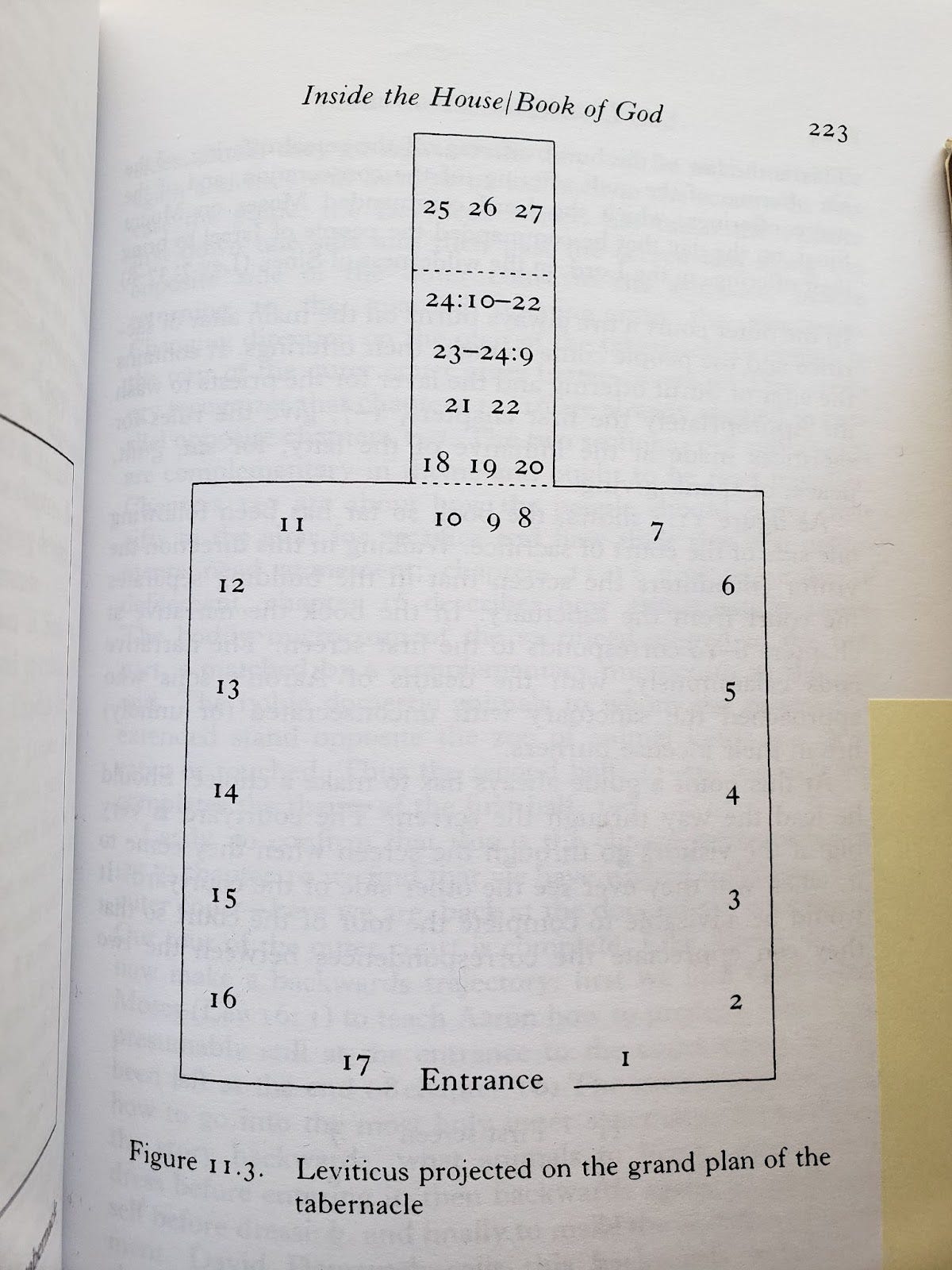

Structuralist anthropologist Mary Douglas, in her book Leviticus as Literature (Oxford University Press, 1999), shares this insight: the text of Leviticus, she maintains, is shaped like the Tabernacle of Testimony. I broadly agree with her, though my outline (see my website) differs from hers in a few particularities, chiefly in that she places ch. 17 at the end of the beginning part, closing a ring with ch. 1. She certainly has good reason to do this, but I place it at the beginning of the second part, finding it better fits the fractal pattern in that position. Douglas’s arrangement (see image below) puts great weight on the distinction of narrative and law, ch. 8–10 and 24:10‑23 being in her estimation the only examples of narrative in the book. I, from my typological perspective, am dubious both that this is an important distinction and that even if it were, there were no other instances of narrative in the book. But to her, the narratives at ch. 8–10 and 24:10‑23 function as screens between the three sections, the first section being a chiasmus and the second being a linear progression. Conversely, in my contemplation of the typology, I see the first section as triadic ascent, and the second as fivefold chiasmus. It is not necessary to see the two models as exclusive of each other, but the differences are worth noting.

And I do find the differences in particularities fascinating because we both agree on the overall shape. Something similar happens with Peter F. Ellis’s book The Genius of John (The Liturgical Press, 1984), in which the author sees the Gospel of John as a fivefold fractal — except his arrangement of the text is wildly different from mine; it’s really lopsided and weird in its particulars. I’ve had a friend who has independently come to the same conclusion. This friend, not following the cosmic chiasmus sequence of typology, produced an outline that also differs from mine, but belongs to the same family of understanding; we both center the Gospel on the raising of Lazarus in ch. 11. Ellis centers the entire Gospel on Jesus walking on the sea at 6:16–21, which is bonkers to me. And yet he correctly, from my perspective, identifies the overall shape of the Gospel as a fivefold fractal, which my friend also independently confirmed. This will seem counterintuitive if one understands perception of the whole shape of a text as emerging from perception of the particulars. If that were the case, witnesses who differ so much in their perception of the particulars should not come to such perfect agreement on their perception of the shape of the whole. Yet here we are.

My suspicion is that this phenomenon is like climbing a mountain. It’s hard to get lost climbing a mountain. Everything converges. Sure, from the base of a mountain, you could take a wrong direction and end up climbing completely the wrong mountain, but as long as we’re climbing the same mountain, traversing the distance from the particulars at the base to the whole at the peak, it’s possible for minds like Ellis’s, mine, and my friend’s to arrive in the same place. That unity doesn’t emerge from the particulars so much as precipitate from our identification of which mountain to climb. It’s when descending a mountain, in attempt to account for the particulars, that divergence easily occurs. Stray from each other a single degree, and two paths can lead to places miles apart. I think the trick to tracing a graceful and happy path is finding consistent fractal patterns that bring one’s understanding of particulars and whole into symbolic harmony. That’s what I’m trying to do, but I digress.

Here is Mary Douglas’s plan of the Book of Leviticus. As mentioned, she sees the passages of ch. 8–10 and 24:10‑23 operating as screens between levels, the first screen chiastically placed in the first part like the veiled entrance into the Tabernacle from the courtyard, and the second screen linearly placed as the cherubic veil outside the Holy of Holies.

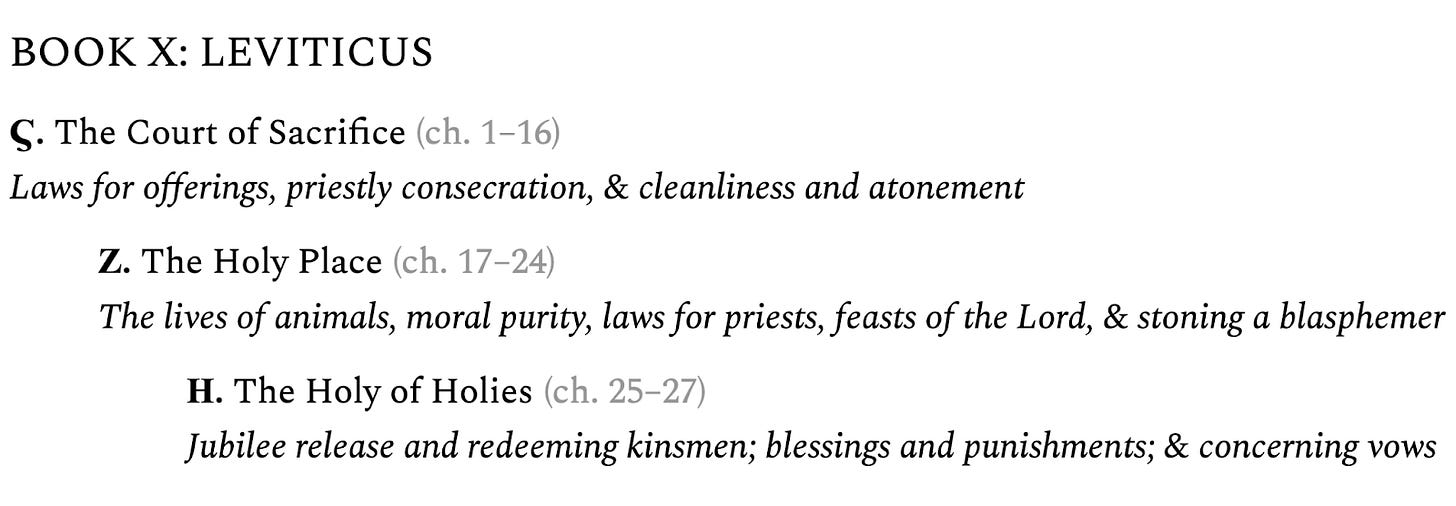

Being an anthropologist, Douglas is keen on mapping the text rather literally onto a model of the Tabernacle as it existed in ritual practice. Striving to perceive the typological meaning of things, I have a less literal approach, but I believe it serves the text more faithfully. Other books of Scripture, after all, also have triadic structures; they have no need of mapping so literally onto the Tabernacle, and neither does Leviticus. They’re all — each such book as well as the Tabernacle itself — following a threefold heavenly pattern for how to approach God. Here is my general three-part outline of Leviticus. Viewed on this level, it only differs from Douglas’s in regard to the placement of ch. 17.

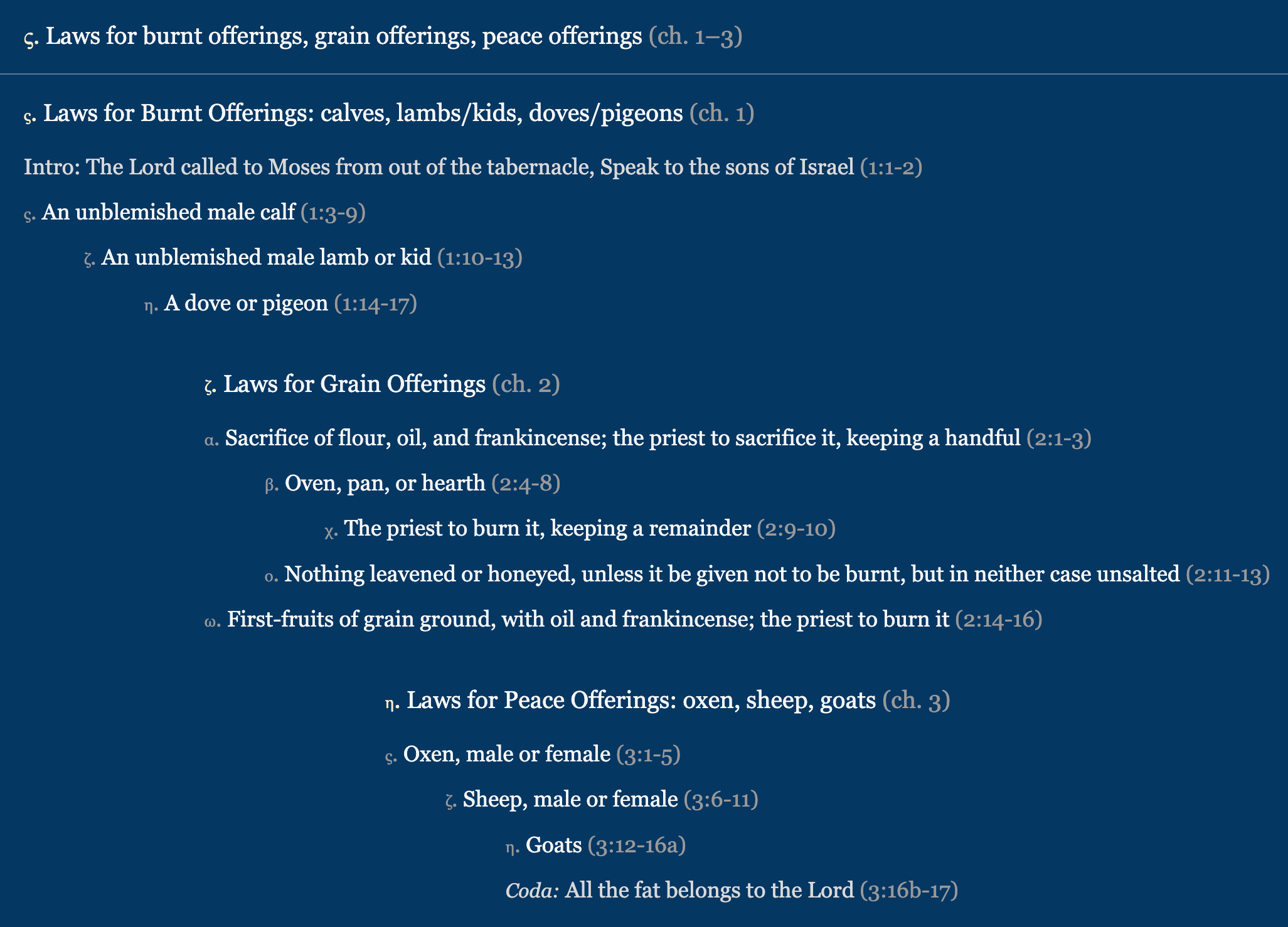

That’s the view from the peak, at least. Looking at the text closer to base level, we see Leviticus begins with laws for (ς.) burnt offerings in ch. 1, then (ζ.) grain offerings in ch. 2, then (η.) peace offerings in ch. 3. The divisions between the three sections are plainly evident, hence the especially coherent chapter numbering. Looking even closer, we see ch. 1 itself clearly divides into three different types of burnt offerings: of the herd (cattle, oxen), of the flock (sheep, goats), and of fowl (dove, pigeon).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Cormac Jones Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.