That angels can’t of themselves know the future

What this tells us about the cosmos we inhabit and the importance of what we do with our lives

I’ve been listening to all of the Lord of Spirits podcast wondering when this topic would come up — that angels can’t of themselves know the future. It hasn’t. I suppose I could have asked them about it at some point, but now I just figure I’ll broach the subject myself and see what comes of it. What sparks my interest now is a friend who recently asked me about the nature of prophecy with just a little context to his question, such that I had to guess a couple times before he revealed exactly where his curiosity lay. That exchange helped turn up these thoughts in my mind, but I maybe should have been thinking them anyway as I contemplate what in the world I do with my terrifying freedom and what things might come about as a result of my action or inaction.

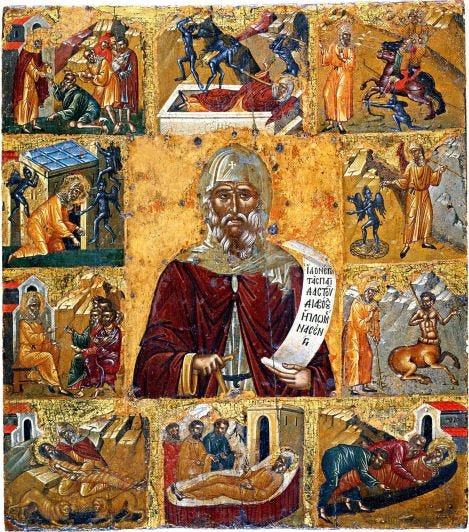

There were Christian monastics before St. Anthony the Great, but since him, all Christian monastics have been his offspring. He made sure to prepare his disciples for the wiles of the demons, and so he taught them about how neither they nor any other creature can by nature know the future. St. Anthony’s hagiographer St. Athanasius the Great recorded his teaching in the following words. I’ll be generous with how much I quote so as to provide plenty of context, and really, what better use of your time is there than reading such texts? St. Anthony teaches,

So then we ought to fear God only, and despise the demons, and be in no fear of them. But the more they do these things the more let us intensify our discipline against them, for a good life and faith in God is a great weapon. At any rate they fear the fasting, the sleeplessness, the prayers, the meekness, the quietness, the contempt of money and vainglory, the humility, the love of the poor, the alms, the freedom from anger of the ascetics, and, chief of all, their piety towards Christ. Wherefore they do all things that they may not have any that trample on them, knowing the grace given to the faithful against them by the Savior, when He says, “Behold I have given to you power to tread upon serpents and scorpions, and upon all the power of the enemy” [Luke 10:19].

Wherefore if they pretend to foretell the future, let no one give heed, for often they announce beforehand that the brethren are coming days after. And they do come. The demons, however, do this not from any care for the hearers, but to gain their trust, and that then at length, having got them in their power, they may destroy them. Whence we must give no heed to them, but ought rather to confute them when speaking, since we do not need them. For what wonder is it, if with more subtle bodies than men have, when they have seen them start on their journey, they surpass them in speed, and announce their coming? Just as a horseman getting a start of a man on foot announces the arrival of the latter beforehand, so in this there is no need for us to wonder at them. For they know none of those things which are not yet in existence; but God is the only one who knows all things before their coming to be [cf. Susann. 42]. But these, like thieves, running off first with what they see, proclaim it: to how many already have they announced our business — that we are assembled together, and discuss measures against them, before any one of us could go and tell these things. This in good truth a fleet-footed boy could do, getting far ahead of one less swift. But what I mean is this. If any one begins to walk from the Thebaid, or from any other district, before he begins to walk, they do not know whether he will walk. But when they have seen him walking they run on, and before he comes up report his approach. And so it falls out that after a few days the travelers arrive. But often the walkers turn back, and the demons prove false.

So, too, with respect to the water of the river, they sometimes make foolish statements. For having seen that there has been much rain in the regions of Ethiopia, and knowing that they are the cause of the flood of the river before the water has come to Egypt they run on and announce it. And this men could have told, if they had as great power of running as the demons. And as David’s spy going up to a lofty place saw the man approaching better than one who stayed down below [2 Samuel 18:24], and the forerunner himself announced, before the others came up, not those things which had not taken place, but those things which were already on the way and were being accomplished, so these also prefer to labor, and declare what is happening to others simply for the sake of deceiving them. If, however, Providence meantime plans anything different for the waters or wayfarers — for Providence can do this — the demons are deceived, and those who gave heed to them cheated.

Thus in days gone by arose the oracles of the Greeks, and thus they were led astray by the demons. But thus also thenceforth their deception was brought to an end by the coming of the Lord, who brought to nought the demons and their devices. For they know nothing of themselves, but, like thieves, what they get to know from others they pass on, and guess at rather than foretell things. Therefore if sometimes they speak the truth, let no one marvel at them for this. For experienced physicians also, since they see the same malady in different people, often foretell what it is, making it out by their acquaintance with it. Pilots, too, and farmers, from their familiarity with the weather, tell at a glance the state of the atmosphere, and forecast whether it will be stormy or fine. And no one would say that they do this by inspiration, but from experience and practice. So if the demons sometimes do the same by guesswork, let no one wonder at it or heed them. For what use to the hearers is it to know from them what is going to happen before the time? Or what concern have we to know such things, even if the knowledge be true? For it is not productive of virtue, nor is it any token of goodness. For none of us is judged for what he knows not, and no one is called blessed because he hath learning and knowledge. But each one will be called to judgment in these points — whether he have kept the faith and truly observed the commandments.

Wherefore there is no need to set much value on these things, nor for the sake of them to practice a life of discipline and labor; but that living well we may please God. And we neither ought to pray to know the future, nor to ask for it as the reward of our discipline; but our prayer should be that the Lord may be our fellow-helper for victory over the devil. And if even once we have a desire to know the future, let us be pure in mind, for I believe that if a soul is perfectly pure and in its natural state, it is able, being clear-sighted, to see more and further than the demons — for it has the Lord who reveals to it — like the soul of Elisha, which saw what was done by Gehazi [2 Kings 5:26], and beheld the hosts standing on its side [2 Kings 6:17].

When, therefore, they come by night to you and wish to tell the future, or say, “we are the angels,” give no heed, for they lie.1

St. Anthony’s emphasis, naturally, is on our demon foes’ inability to see or know future events, but his statement is clear in the line that I’ve emphasized, “God is the only one who knows all things before their coming to be” — their “genesis”, that is. The line conveniently paraphrases the forty-second verse of the Susanna pericope in the Book of Daniel, which, if one searches, will lead one to other similar patristic sayings. Angels may be able to relay divine revelations about the future as it is first of all revealed to them, but they can’t of themselves (in other words, by their nature) know the future.

I find this practical observation so enlightening because I imagine it could be counterintuitive to a rational mind constructing an image of the cosmos by human means of dialectic and analogy. Eternity and time are analogically like heaven and earth, the immaterial realm and the material realm. Angels belong to the immaterial realm, not the material realm. Therefore, they belong to eternity and exist outside temporal limitations, right? Nope, wrong actually. Those who put off abstract knowledge of the cosmos for the sake of pursuing the Tree of Life, following the commandments in loving obedience, learn from practice of the virtues that the truth is something different from that. (Glory to God, I relish any and all such discrepancies.)

Through the creation of breath-and-dust anthropos, the heaven and the earth — and eternity and time as well — are inextricably bound with each other. The hypostatic unity of the human being makes it so. Humans like angels are nous-endowed, which comes with the capacity of free will. Both noesis and free will are properties belonging to the immaterial realm, but due to humans having flesh, the execution of their will has a temporal dimension. St. John Cassian was a man from the land now known as Romania, who as a young monastic traveled around Egypt visiting the holy elders there, gleaning their wisdom a generation or two after the passing of St. Anthony. Later in life he wrote extensively about it in his Conferences. In the Fourth Conference, called “On the desire of the flesh and of the spirit,” he passes on this invaluable explanation by one Abba Daniel of how free will works in an embodied spirit. Again I quote liberally. Abba Daniel teaches,

And so it will happen that when, on account of the lukewarmness of this indolent free will that we have spoken about, the mind has turned too readily toward the desires of the flesh, it will be restrained by the desire of the spirit, which is not in the least inclined to earthly vice. On the other hand, if through an immoderate fervor resulting from an overflowing heart our spirit has been snatched up to things that are impossible and ill-advised, it will return to its proper equilibrium thanks to the weakness of the flesh. Then, transcending the very lukewarm condition of our free will, it will proceed with all due moderation and with toilsome effort along the path of perfection.

We read in the Book of Genesis that something similar was ordained by the Lord with regard to the construction of that famous tower, when a confusion of tongues suddenly occurred and repressed the sacrilegious and wicked attempts of men. For a disharmony would have remained there in opposition to God, and indeed in opposition to those who had begun to tempt his divine majesty, unless by God’s design a diversity of languages had created division among them and had, by their dissonance, forced them to advance to a better state, and unless a good and beneficial discord had recalled to salvation those who had been persuaded to destroy themselves by their wicked agreement. Thus when division occurred they began to feel the human frailty that previously, elated by their evil conspiracy, they had been unaware of.

From the diversity in this conflict there arises a delay, and from this strife there comes a pause which is so beneficial to us that when, due to the body’s resistance, we cannot immediately pursue to the end what we have wickedly conceived, we are sometimes changed for the better because of the subsequent remorse or the reconsideration that usually follows upon postponing a work and thinking about it in the interval. And those who we know are restrained by no fleshly hindrance from fulfilling the desires of their wills — namely, the demons and evil spirits — we hold to be more detestable than human beings, although in fact they have fallen from a higher order of angels, because as soon as they have conceived of something wicked they at once pursue it to its evil end. In them possibility is immediate to desire, for as swift as their mind is to think of something, equally swift is their pernicious and unrestricted substance to carry it out, and since the ability to do whatever they want lies near at hand, no salutary hesitation intervenes for them to change what they have wickedly conceived.

For a spiritual substance which is free of the flesh’s resistance has no excuse for an evil choice arising in itself, and thus there is no pardon for its wickedness, because it has not been provoked to sin from without, as we are, by any assault of the flesh, but is inflamed by the viciousness of an evil will alone. Therefore its sin is unpardonable and its disease irremediable. Just as it succumbs without the involvement of any earthly matter, so it cannot obtain forgiveness or a place of repentance. It is clear from these facts that this struggle of flesh and spirit against one another which rages in us is not only not bad but is even of great benefit to us.2

The whole phenomenon of history is a result of this biological contraption called man combining eternity and time in one existential experience. This means, among other things, that humans are capable of repenting in a way that angels can’t. Their natural will is a consequence of having a heavenly aspect like angels, and yet it exists in time, time understood as akolouthia, an ordered sequence of events. This makes future events in time sincerely unknowable to heavenly creatures, because fleshy man really is bestowed noetic freedom. The outcome of future events, therefore, cannot be known to angels because humans are free to change things. Humans, of course, can’t know the future either, for the same reasons. Only God, the Creator of eternity and time, is in a position to know all things therein.

St. Maximus the Confessor, that seventh-century monastic who through ascesis, theoria, and primarily grace mastered all doctrine Christological, anthropological, and cosmological, ties these observations to the unknowability (from a creaturely perspective) of essence. For we creatures, angels and humans both, not only can’t know God in His essence, we also can’t know anything, even ourselves, in essence. In Ad Thalassium 60, a tract about how it was that “Christ was foreknown before the foundation of the world” (1 Pet. 1:20), St. Maximus writes,

Since, therefore, no being in absolutely any way at all knows what itself or any other being is in terms of its essence, it follows that no being by nature has foreknowledge of any future events. Only God, who transcends beings, and who knows what He Himself is in essence, foreknows the existence of all His creatures even before they are brought into existence. And in the future He will by grace confer on those beings the knowledge of what they themselves and other beings are in essence, and reveal the principles of their genesis that pre-exist uniformly in Him.3

I think essence, in these terms, is analogically like the one-way speed of light, which we fundamentally cannot measure. Because we exist within light, and can only perceive by means of light, we can only measure the two-way speed of light — that is, the speed of light as it travels a full circuit from the original point of our subjective perspective (point A) to another point (point B) and back to our original point of subjective perspective (point A). The objective perspective necessary to measure light traveling in one direction from just a point A to a point B could only be accessible to the one who said “Let there be light” in the first place. It’s the same with essences. Within creation, we cannot attain a global perspective of anything created. Similarly we cannot know the future; we lack a global perspective of our life. Angels, despite not having material bodies, are in the same boat. They cannot know what their enfleshed noetic brothers are going to do, nor what’s going to happen with the world that is subject to human volition.

But God knows all things, whether we perceive His knowledge as foreknowledge or as memory. Through the story of deification in Christ, foreknowledge of things before their genesis can be passed on to us. But such transmission will only happen if it aids the process of deification. Where foreknowledge of future events would be detrimental to our spiritual lives, which is generally the case with very few exceptions, out of God’s love for us it is going to be withheld. In the perfection of theosis attainable in the eschaton — again out of God’s love for us — nothing is withheld. And so St. Maximus refers to the knowledge of essences being passed on to creatures “in the future” (μέλλοντος [PG 90.625A]).

But tastes of the eschaton are available to us humans now by means of the chiastic causality that crowns the linear causality of time (see last year’s article on Mid-Pentecost for a depiction of this bi-causal relationship). Notice how in Greek when we’re talking about not knowing things before their coming-to-be, we’re talking about their genesis. Genesis is not just a past event, but a future event — and a present event. Just as we have this idea of “Apocalypse Now” so there is also a “Genesis Now”. The whole chiastic pattern of creation is fractally present to us according to a divine causality which operates chiastically, even if our human causality, lovingly preserved and illuminated, operates linearly.

And “Apocalypse Now” should be understood as “Revelation Now”. When angels reveal the future to the prophets, or when saints display clairvoyance, whether the insights take the form of heavenly patterns or earthly events, divine energy is penetrating our lives. When, say, a young man asks his guardian angel for help, that he may know whether he should get married and start a family or enter a monastery, the angel can only pass the request up the chain. The angel doesn’t of himself know what should or will happen because that young man is actually, even terrifyingly, free to decide. Yet the existence of whole persons, the young man’s potential offspring, depends on what he chooses! Will they have a genesis or not? No human is created apart from God’s will that they be created, and it is God that creates each child. But no childbirth transpires without parental participation. When the Archangel Gabriel approached the all-holy virgin Mary, he genuinely did not know what her response would be to the proposition he was passing on to her, which it truly was up to her to accede to or not. No angels of themselves could possibly have foreseen the Incarnation before the moment in linear history when it happened — the same Incarnation foreknown before the foundation of the world and chiastically causing all the events linearly preceding it.

So what should we do with our lives? And how great are the ramifications of what we decide! The predicament of our ignorance is enough instigation to drive us fully into prayer to our Creator and Redeemer, the Knower of all things, He who loves us and shares with us all His glory. That, no doubt, is the point. What should we do with ourselves? Well, what does the Godlike love within us say?

St. Athanasius the Great, Life of Anthony 30–35, td. by H. Ellershaw, NPNF 2.4, ccel.org/ccel/s/schaff/npnf204/cache/npnf204.pdf. Emphasis added — though Ellershaw’s line, “but God only is He who knoweth all things before their birth,” has been altered by me based on the Greek at PG 26.889B: ἀλλὰ μόνος ὁ Θεός ἐστιν ὁ πάντα γινώσκων πρὶν γενέσεως αὐτῶν.

St. John Cassian, The Conferences, “The Fourth Conference: On the Desire of the Flesh and of the Spirit” XII.6–XIV, td. by Boniface Ramsey (Paulist Press, 1997), pp. 163–64. I might mention I recently encountered Fr. Stephen De Young relaying this teaching during a tangent on his Whole Counsel of God podcast, on Psalm 7, here.

St. Maximos the Confessor, Ad Thalassium 60.8, in On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios, td. by Fr. Maximos Constas (The Catholic University of America Press, 2018), pp. 431–32.

This is awesome, Cormac. Thank you as always

A lovely reflection, great choice of icons