Here I pick up with the promised sequel to “The Lenten Octave,” describing the octave of Sundays in the Pentecostarion, from Anti-Pascha through Pentecost and the Sunday of All Saints.

I typically struggle to live right while passing the time between Pascha and Pentecost. Feasting can be very spiritually difficult (I wrote a little about this last Bright Week). In order to do it right, you almost have to be perfect. Any deficiencies in one’s Lenten repentance can be revealed as tragic flaws during Paschaltide. As spiritual exercises go, the process is immensely beneficial! But it requires attention, and here I wish to pay attention to that season which should represent the perfection of our liturgical worship, according to this threefold schema:

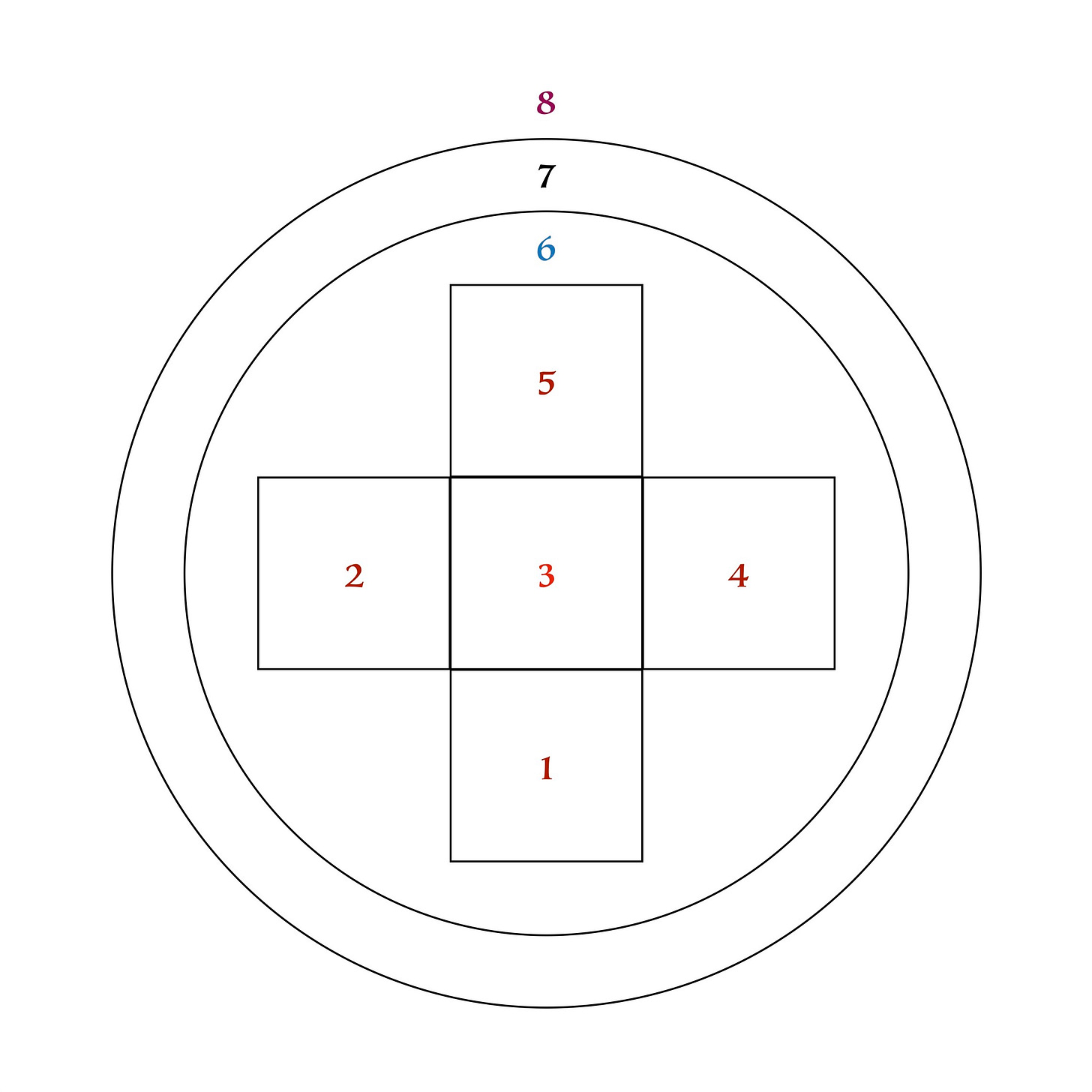

Each of these three layers of the liturgical year internally takes an octave shape, the sevenness of time being crowned by an eighth-day eternity. In the case of Lent and the Paschal season, the octaves overlap. I teased this chart last time, when discussing the Lenten octave:

The fifty days between Pascha and Pentecost — in Jewish terms: Passover (Pesach), the liberation of Israel from the grasp of Egypt by the death of the firstborn, and the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot), the giving of the Torah on Mt. Sinai, forging a covenant between God and His people, associated also with the Feast of Firstfruits (Bikkurim) — I believe provides the paradigm for both the Lenten period and the Octoechos. Fifty is a Jubilee, the symbolic eighth day after a period not of seven days but of seven weeks (7 × 7 + 1 = 50). This eighth day contains everything, so as a fractal it can be perceived to contain a week within itself; an eighth week is an appropriate way to celebrate it. And so we have this eight-week liturgical pattern in the Orthodox Church: as for the Feast of Weeks, so for the Octoechos and the Lenten Fast.

The Lenten Fast, though, readers will recall, begins on a Monday, and so each Sunday of the Fast operates as a crown to the week preceding it. This pattern continues through Palm Sunday (crowning the week of Lazarus’s death and resurrection), Pascha Sunday (crowning Passion Week), and Anti-Pascha (crowning Bright Week). As we switch over into the weeks of the Pentecostarion, however, the relation of Sundays to their weeks reverses, beginning with Anti-Pascha, which is also Thomas Sunday. Thomas Sunday is to be contemplated as the head of the week succeeding it. This pattern is expressed liturgically by each Sunday of this period operating like a week-long feast, its troparion and kontakion staying in use and its canon heading the odes at Matins each day through the following Saturday (notwithstanding the interruptions presented by the feasts of Mid-Pentecost and Ascension). The parade of week-long afterfeasts reaches its end only in the Sunday of All Saints, the octave of Pentecost, the day after which immediately sees the beginning of the Apostles’ Fast and the switch from the Pentecostarion to tone eight of the Octoechos for daily services — and the whole yearly journey starts anew.

Α. Thomas Sunday

The eighth day of Pascha is both Anti-Pascha and Thomas Sunday, a recapitulation and the profoundest demonstration of everything Paschal. Musically the first tone, so prominent in the Paschal service, is returned to on this day after cycling through all eight tones during Bright Week (minus the grave tone). This sets in motion the eight Sundays of the Pentecostarian, all clearly numbered one through eight, according to the tone of resurrectional hymns that are used. When Ascension comes along, and on that Sunday you’re singing in the sixth tone.... When the Descent of the Holy Spirit transpires and you’re singing in the seventh tone (at the Matins canon anyhow; on Pentecost Sunday the resurrectional hymns are withheld and there is a greater variety of musical tones).... When the Sunday of All Saints arrives and you’re singing in the eighth tone... the numerological symbolism shines clear as day, and it all traces back to the eighth day of Pascha, the first of a new week of Sundays, Thomas Sunday. The whole Pentecostarion period is an octave within an octave, a fractal sweet spot full of divine descension and human ascension.

From the start, on Thomas Sunday, Christ is risen from the dead, and that He is risen from the dead is established beyond doubt by the Lord’s loving condescension to doubting Thomas. Indeed, blessed are those who have not seen and yet believed — but blessed also is Thomas, who required validation from sensory observation. God does not despise the scientists; the ones ready to proclaim Jesus as Lord and God upon receiving the empirical confirmation they seek even serve a purpose to all mankind, establishing beyond reasonable doubt the Incarnation, Death, and Resurrection of God the Word. Thomas’s immersion in doubt and emergence in faith is the experience that testifies to the reality of the pattern. And so Christ’s descent into death and ascent into life is destined to be matched festively by the ascent of man to God and the descent of God to man: the octave begins.

Β. Sunday of the Myrrh-bearing Women

On the second Sunday of this octave, still basking in the glow of Pascha, we return to the empty tomb. In doing so we celebrate that aspect of the Resurrection which takes place in a graveyard. Thus the theme of death, or separation from life, appropriate for beta-symbolism, is centered, but it’s turned on its ear. This Sunday is a remembrance of the lamentation that ends all lamentation, a recollection of the exile that was experienced by those who witnessed the Death and Burial of Christ — an exile that summarily exiles what it means to be exiled, as announced by a luminous angel to the women in mourning.

In the beginning, at the instigation of a fallen angel, the desire of Eve led her astray and all her offspring with her; the story of that fall makes up the first beta-chapter of Genesis. Here the beta-chapter of this octave reverses that fall, showing the desire of the Myrrh-bearing Women, those who gather around the Body of Christ in love, regardless of how we humans may misinterpret His promises to us. The Church together with them laments the pain of loss instead of like Eve salivating over the potential for gain. But the sorrow is turned to joy, a joy which after the fall could not come except through sorrow.

The Gospel reading for this Sunday is from the end of Mark, a momentary diversion from the readings from the Gospel of John. Moving forward from here, we will turn from readings directly about the Resurrection narrative to passages in John that explain the Resurrection typologically. Of the other notable liturgical features of this Sunday, I will mention how interesting it is that the lengthy Matins canon of the Myrrh-bearers is less to the Myrrh-bearers than it is from the Myrrh-bearers. Most of the verses are prayers to the Savior, as though we are joining our words to those of the holy women. Actually we’ll find this pattern common as the Sundays go on; the first few verses of the Matins canons specific to each Sunday are generically about the Resurrection before touching on the Sunday theme, commonly doing so with just one verse. But as usual the kontakia of the feasts express the inner meaning. For this Sunday’s kontakion we sing, “Thou didst command the myrrh-bearers to rejoice, and didst console the lamentation of our first mother Eve, by Thy resurrection, O Christ God; and didst command Thine apostles to preach: The Savior hath risen from the tomb!”1

Χ. Sunday of the Paralytic

At the sheep’s pool in Jerusalem called Bethesda, the Archangel Michael himself — it is made clear in the liturgical tradition of this Sunday — is the one who upon his seasonal arrival heals from ailment the first person to enter the moving waters (a verse to St. Michael is included in each ode at the Matins canon). Archangel Michael, besides being the guardian of Israel, is associated first and foremost with the final judgment, he being tasked with delivering Satan to his ultimate punishment. This annual miracle at Bethesda, therefore, betokens the restoration to health that all worthy souls will receive when they pass through the waters of the end of the world. In the Gospel of John, this Sunday’s reading (John 5:1–15) is followed by a discourse on the general resurrection and the final judgment. Indeed John chapter 5 occupies the omega-position of the first of five acts in that Gospel (see outline) — after the encounter with the Samaritan Woman in chapter 4, not before.

But here in the weeks leading to Pentecost, the Sunday of the Paralytic recontextualizes the story so as to occupy the central chi-position. Due to its fractal quality, the story of Christ contains all stories within itself, and different contexts can bring out different aspects of each individual story. The seasonal healing that goes on in the sheep’s pool may betoken the general resurrection, but the healing of the paralytic kept waiting thirty-eight years occurs at the command of the incarnate Word of God adjacent to the pool. Thus this story also symbolizes the Resurrection of Christ in the midst of history, besides also the general resurrection at the end of history. In a chiastic sense (that is, according to chiastic causality), the chi-resurrection and the omega-resurrection are united, even if in linear human experience there is an interval between them. We experience this liturgically at Pascha, when the Resurrection of Christ is experienced both as that event which occurred in the center of history and also as that ultimate event which inaugurates the kingdom which is to come — and now is (cf. John 4:23).

So in this context, the healing of the paralytic, a man whose body was as though dead, represents the Resurrection of Christ typical of chi-symbolism. At “Lord I Have Cried” at Great Vespers, we sing, “Seeing Thee, [O Lord,] the paralytic, who was like an unburied corpse, cried out, ‘Have mercy on me, O Lord, for my bed hath become a coffin for me. Of what profit is life for me?’”2 Upon being healed, the man (named Jarah according to the Synaxarion) is told to take up his bed, symbolic of his body, and walk. This occurs on the sabbath because it is Jesus — the true Sabbath, as God resting in creation — whose rest in the tomb on the Great Sabbath effects any and all resurrection.

Moreover, John 5:1 says this healing occurs at the time of a Judean feast, the occasion for Jesus being at Jerusalem. Not specified in that verse is which of the three feasts that occasion travel to Jerusalem it was, Passover, Pentecost, or the Day of Atonement. Traditionally it is interpreted to be Pentecost since in the narrative context it follows the events at Passover related in John 2, these initial chapters of John’s Gospel being understood as set during Jesus’s first year of ministry. Also the sheep’s pool ties symbolically to Pentecost via the baptism of the nations. Therefore, just as the central Sunday of the Lenten Triodion focuses on the Cross so pivotal to the sabbath Sunday of that octave (Pascha), so here the events celebrated on this chi-Sunday occur on the feast celebrated on the zeta-Sunday, Pentecost.

This centrality of the Sunday of the Paralytic is underlined further by its would-be week-long afterfeast being interrupted by Mid-Pentecost on Wednesday. That’s the twenty-fifth day of Pascha, the halfway point to Pentecost. It occurs already in the third week of this octave because the days are counted from Pascha, but the octave begins on Anti-Pascha, plus Pentecost occurs already on the seventh Sunday of the octave. Symbolically it all checks out perfectly, even though mathematicians may struggle to understand how a third week could be central to a set of eight.

Concerning Mid-Pentecost, with its seven-day afterfeast cutting also into the front half of the Week of the Samaritan Woman, I said enough in my post last year.

Ο. Sunday of the Samaritan Woman

Mid-Pentecost’s obsession with water continues as we pass from the sheep’s pool called Bethesda to Jacob’s Well in Samaria. The Gospel story of the Samaritan Woman, who is known to the Church as the holy Martyr Photini, has a tremendous amount of symbolic layers to it. As locations go, a well is a very feminine image: a reserve of life-giving water accessed by digging deep within the earth. In the Torah wells were where the wives of patriarchs were found, such as Rebecca for Isaac and Rachel for Jacob. And now the Bridegroom, the King of the Jews, comes searching for his compromised bride in Samaria by a well (a well, no less, dug by Jacob and gifted to his son by Rachel, Joseph). Indeed marriage is the most prominent theme here — marriage between man and woman, heaven and earth, Jerusalem and Samaria, Judean and Gentile, Christ and the Church, God and man, Spirit and worship. This chapter in John forms the omicron-passage of that Gospel’s first cycle (see outline), and this Sunday heads the omicron-week of the Pentecostarion octave, and in both cases does so by highlighting the symbolism of marriage — “but I speak concerning Christ and the church” (Eph. 5:32).

Hence meaningfully does this encounter take place in Samaria, because the Samaritans who supplanted the ten tribes of the Northern Kingdom represent an illicit union between Israel and the Gentiles, which union Christ has come to set right. When it is revealed that St. Photini has had five husbands and the sixth is not her husband, one symbolic meaning of that personal history is that the Samaritans have had five husbands in that they accepted the five books of the Torah, though its text was corrupted for polemical reasons and they rejected all the writings of the prophets after Moses. In either case, the suggestion of the story is that Christ has come to be the seventh husband, as He is the true Sabbath, God resting in all humanity, even the Samaritans, even the nations in the uttermost parts of the earth (cf. Acts 1:8). The result of this union is the Church.

Chiastically, meanwhile, the Sunday of the Samaritan Woman pairs with the Sunday of the Myrrh-bearing Women by again participating in the reversal of Eve’s fall. At “Lord I Have Cried” at Vespers, the first verse for the Samaritan Woman bears this out: “Thou didst arrive at the well at the sixth hour, O Wellspring of miracles, in pursuit of the fruit of Eve; for Eve at the same hour departed from paradise because of the deception of the serpent [cf. Gen. 3:8].”3 The fruit of Eve that Christ is pursuing, recall, is the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil; He seeks it at the sixth hour (John 4:6) because at the sixth hour He would be crucified (19:14), tasting the curse of death that Eve brought upon herself. Then by His Death and Resurrection He redeems the life of Eve and founds the Church of the nations.

Moreover, at the Canon of the Samaritan Woman for Matins, among the generic verses for the Resurrection, specific mention is made of the Myrrh-bearing Women at each of the odes one through seven.

Ω. Sunday of the Blind Man

Chiastic parallels continue as Thomas’s requirement of sensory observation of the risen Christ before worshiping Him on this octave’s first Sunday is matched on the fifth Sunday by the man blind from birth being gifted sight by Jesus, eventually to see Him as the Son of God and to worship Him.

In the Gospel of John, this story actually occupies an omicron-position in the second section (see outline) because the distinct responses to Jesus of the healed blind man on the one hand, and of the Pharisees on the other, match evenly with the diverse reactions of the Gentiles and the Jews to the news of the Resurrection in the era of the Church. Again, though, as with the Sunday of the Paralytic, liturgical recontextualization brings out a different typological aspect of the story.

One aspect of this story functions actually not as omicron- or omega-symbolism, but as alpha-symbolism. I refer to the act of creation Christ engages in when He makes new eyes for the blind man born without them. He was born without them not because he or his parents sinned, “but that the works of God should be made manifest in him” (John 9:3). Just, then, as God the Word made man of breath and dust, the same Christ now takes spit and dirt and continues His creation, which is perfected by the washing of the Spirit whom He sends (Siloam, the pool where the man is to wash, means “Sent”; John 9:7).

So symbolically — sacramentally even — this healing reveals Christ as the Creator from the beginning, the Son and Word of God through whom all things come to be. The blind man confesses as much after being given sight. But typologically the new creation of heaven and earth, experienced in the general resurrection, is being indicated here also. The man is born blind so that “the works of God should be made manifest in him.” The works of God do not end with Genesis and the fashioning of nature. We are all naturally born blind to God in that humanity cannot of its natural capacity see the One who made us. In order to see the God above and beyond our nature, we have to be given a capacity of sight that is itself above and beyond our nature, like a new pair of divine eyes. This is the gift of the Holy Spirit who is sent to us. Nothing short of deification is sufficient to see God. When the saints see God, it is the divine energy within them that is seeing God for them. That is, it is indeed they who are seeing God, but they do so according to an energy, an activity, beyond their human capacity. And so the Holy Spirit reveals the Son, and the Son reveals the Father. The means of our receiving this gift is the Incarnation of Christ and the washing of the Holy Spirit.

And this act of a second creation, this deification, is an eschatological event, as in it pertains to the eschata, the “last things”. There are no further stages of life beyond deification; it is a creation that goes on and on forever. The healing of the man born blind is a revelation of Christ as the Alpha and the Omega. Contextually the omega aspect is the focus on the Sunday of the Blind Man, for the divine ability to see the divine, typified by the blind man being healed so as to see the man Jesus as the Son of God, occurs not just with divine or noetic eyes, but with the man’s very material eyes, newly remade — a sign of the resurrection of the flesh when not only is divine energy conferred to the mind, but the mind’s divinized energy is conferred to the body and theosis permeates everything.

This ultimate deification is absolutely necessary for what comes presently in the liturgical cycle. For the risen Christ visited with His disciples over the span of just forty days. Already on this Sunday, then, for the first time in the Pentecostarion, the katavasias capping the odes at Matins are not of Pascha, but of Ascension, in anticipation of the fortieth day of the Resurrection that upcoming Thursday. Hence the normally week-long afterfeast of the Sunday is abbreviated; in fact there’s just the Monday and the Tuesday, as Wednesday is reserved for the apodosis, or “leave-taking,” of Pascha, when the Paschal service is repeated and the troparion “Christ is risen” is sung for the last time. Forty-day periods are always in preparation for something, and we’re about to see what.

But for now we contemplate the healing of the man blind from birth, as at Matins we pray the doxasticon at Praises: “For in Thy goodness Thou wast revealed on earth to be both God and man; and didst grant twofold healing unto the infirm. For Thou didst not merely open the bodily eyes of him who was blind from his mother’s womb, but the eyes of his soul as well. Wherefore he confessed Thee to be the hidden God.”4

Ϛ. Afterfeast of Ascension – The First Ecumenical Council

Holy Ascension is a major feast and a landmark in this octave, but because it takes place on the fortieth day of Pascha, it lands on a Thursday not a Sunday. It’s no matter — what the Church celebrates on the Sunday in the afterfeast of Ascension (during which we’re still singing all the hymns appropriate for that feast) is just another way of saying the same thing as the Ascension.

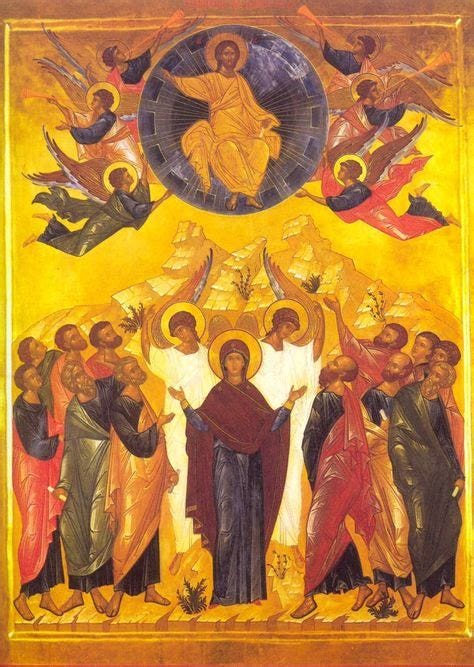

Christ as the Son of God was never not seated with the Father in the heavens. From the Mount of Olives the disciples saw the Lord in the flesh taken up into the heavens and removed from their sight by a cloud (Acts 1:9), and this was an historical event that happened in time. According to chiastic causality, however, the Incarnation which begins at the Annunciation and the Ascension from the Mount of Olives are parts of the same divine motion; they are contained within each other. The incarnation of God and the deification of man are two ways of saying the same thing. The descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost is likewise united to this one divine motion, but meaningfully time sequences these events separately; this week we celebrate the Ascension. This week is not yet about the Spirit of the Church, but the Body of the Church — the Body of Christ.

The body of Christ ascends into the heavens. But at the same time the disciples assembled on earth, iconically centered around the Mother of God from whom Christ receives His body, are the Body of Christ. The Church that partakes of the Body of Christ is the Body of Christ. The risen Jesus’s last words in the Gospel according to St. Matthew are “Lo, I am with you always, even unto the consummation of the age” (Matt. 28:20). Any understanding of the Ascension as a departure, as a kind of de-incarnation — which is a pattern of belief in the overly temporal-minded Latin West since the Schism — could only be either a result of, or productive of, loss of membership in the Church. Christ is with the Church always: He lives, He is risen, which is to say He is not separate from His Body.

But in the Ascension of Christ, the disciples en masse are made to fully realize the meaning of their confession that Jesus is the Son of God. Jesus is fully God, no less so than His Father. Given to expect the descent of the Holy Spirit, which event they were already given to taste on Pascha Sunday forty days prior (cf. John 20:22), and seeing Jesus in the heavens received by a cloud — which form the Spirit often took in the Old Testament, as on Mt. Sinai or at the consecration of Solomon’s Temple, and also as recently as the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor — the disciples were having revealed to them the full divinity of the Spirit as well. This is deification in progress. It is altogether one motion, but it is experienced and can be contemplated in three moments: purification, illumination, and perfection. That’s what these last three Sundays of the Pentecostarion octave signify. They are the stigma (6), the zeta (7), and the eta (8). Ascension on the fortieth day is about preparation, another name for Friday, the sixth day, even as forty-day periods are symbolically related to six-week periods, as we learned in the Lenten cycle. Ascension is theosis as preparation, or purification, purifying the Church’s mind of all wrong perceptions of the Triune God.

This is where the First Ecumenical Council comes in. The Holy Church Fathers gather in Nicaea in 325 to reject the Arian belief that Jesus was less than consubstantial with God the Father. In doing so, they accomplish nothing less than a reenactment of the Ascension of Christ from the Mount of Olives. The singular human body of Christ is recognized as united to the Father in divinity through the Person of the Son who exists before all ages consubstantial with the Father — recognized, that is, by the plural Body of Christ gathered as one here on earth. In choosing the First Ecumenical Council as a theme for the Sunday in the afterfeast of Ascension, the Church has identified a but slightly different way of saying exactly the same thing as that great feast. The typology is identical.

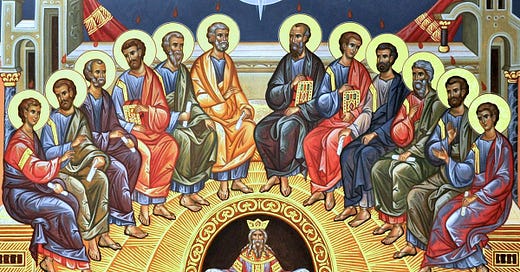

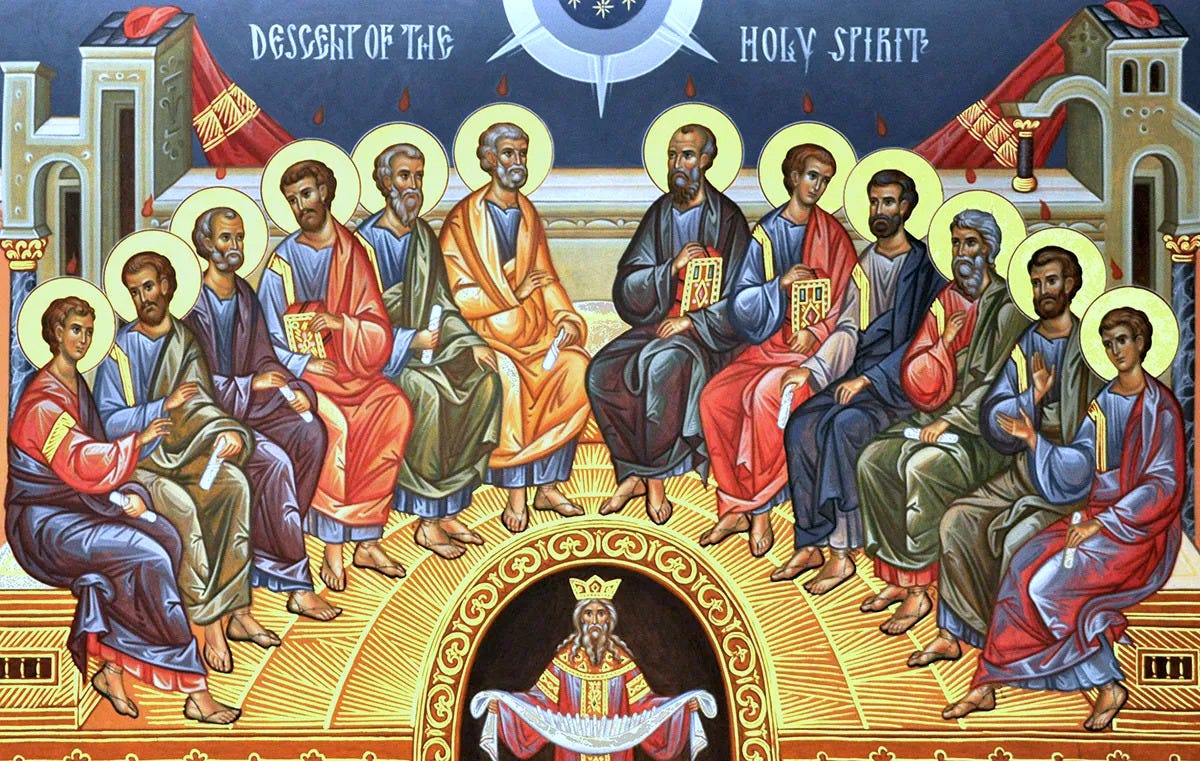

Ζ. Holy Pentecost – Descent of the Holy Spirit

So here we arrive at the initiation of what we have been preparing for this whole time. The covenant at Mt. Sinai between God and His people is at last fulfilled forever, for at Pentecost as the Prophet Ezekiel says (in a passage read at Great Vespers for this Sunday), “Thus saith the Lord... ‘I will put My Spirit in you, and will cause you to walk in Mine ordinances, and to keep My judgments, and do them. And ye shall dwell upon the land which I gave to your fathers; and ye shall be to Me a people, and I will be to you a God’” (Ezek. 36:27–28).

Pascha Sunday, for its part, occurs seventh in order in the Lenten octave because Passion Week is when the Son of God enters Hades and the Resurrection makes contact with history. Likewise Pentecost is the sabbath of the Pentecostarion octave because the seventh week in this sequence, which counts from Anti-Pascha, is when the Holy Spirit enters history, God resting in His saints, God blessing all creation. True, Pentecost is the fiftieth day of Pascha, and as such functions as an eighth day in that regard. The opening canon for Pentecost at Matins is in tone seven in keeping with the other Sundays, but the troparion and kontakion are in tone eight. And the week of Pentecost does culminate in All Saints, the eighth Sunday of the Pentecostarion octave, so it contains eighth-day symbolism in this weekly octave structure I’ve been demonstrating — just as Pentecost contains the sixth-week symbolism of Ascension before it as well. Ascension, Pentecost, All Saints: they’re are all of a piece, one single divine motion with a single pre-eternal cause. So of course Pentecost is the fiftieth day, the archetypical Jubilee. But it is also the central instigation of a pattern that is ordered in time as a six–seven–eight sequence, and so is contemplated in that fashion.

Pentecost is the sabbath Sunday in the sequence because on it we witness God resting in His creation, but sabbath symbolism is also about death, as in Holy Saturday, the Great Sabbath, the seventh day of the seventh week of Lent. Pentecost can be considered a type of death once you learn to contemplate death not in its corrupt mode, which sees a breakdown of hierarchical order and the separation of cosmic layers, but in its original mode according to its logos: succinctly put, death is whenever something higher pours itself into something lower. Yes, when we sinners do this, such as when we pour our minds into our senses, we experience this death as corruption. But when God enacts this motion out of love rather than in sin, well, not only is cosmic hierarchy not disrupted, this is the very means by which cosmic hierarchy is created! Both the acts of creation (the outpouring of being into that which has no being) and Incarnation (the outpouring of divinity into that which has no divinity) are types of this loving death, a death which does not work division but to the contrary brings all into unity by a corresponding resurrection.

Christ’s Death and Resurrection are one motion (in a word, Pascha), as are His Incarnation and Ascension — a different layer, in fact, of the same parabolic motion (technically known as the “economia”). Pentecost is but a different facet of the same. The emphasis is on death, though, in that this feast marks the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon all flesh (Joel 2:28, read at Great Vespers). The cosmic result of this divine action is a movement from one to many, which is another way to contemplate the logos of death. According to the corrupt mode of bodily death, for instance, that which is one body disintegrates into a great many parts. The disintegration that occurred at the Tower of Babel follows the same pattern, a corrupt mode of spiritual death. Pentecost, however, fulfills this pattern as it is meant to occur. That which is higher pours itself into that which is lower, and the oneness of God passes into the multiplicity of creation without losing its oneness. And thereby is oneness bestowed on multiplicity; that which lowers itself in love automatically rises again. When the one moves to the many, the many become one.

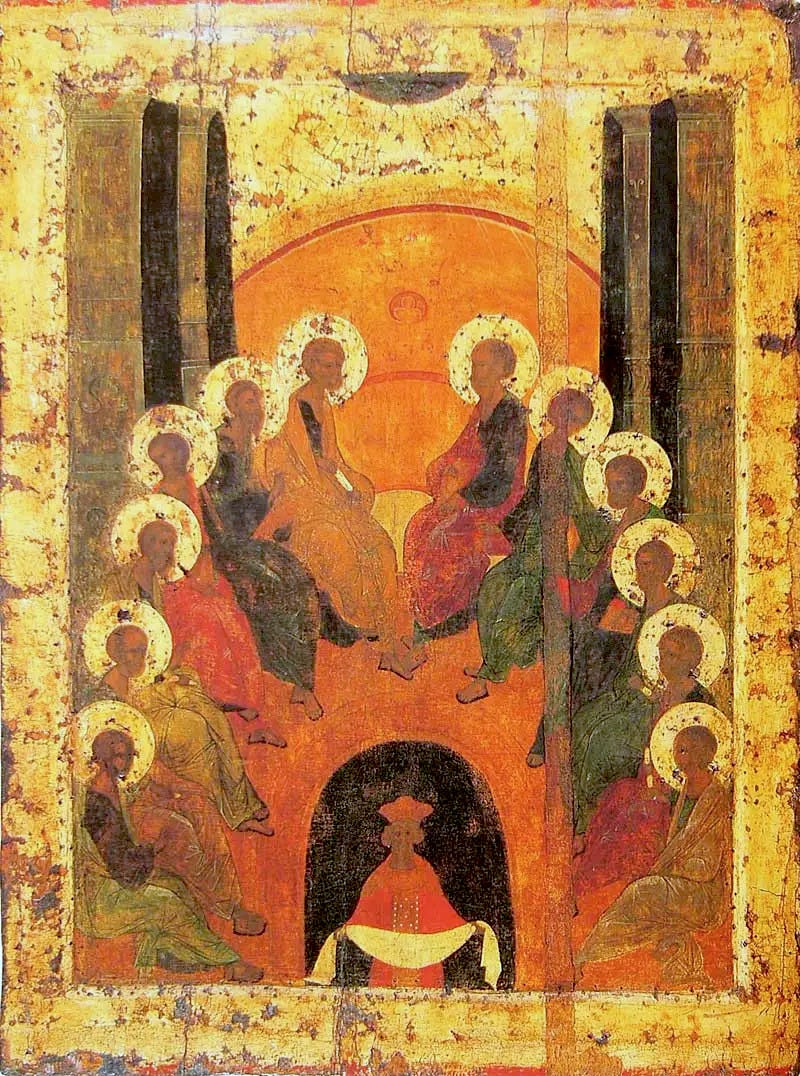

I’m trying to explain things in philosophical concepts for the sake of mental clarity, but at Pentecost what I’m describing happens rather in a story of intuitively perceived symbols. The disciples of the risen Jesus gather at Jerusalem to celebrate God’s covenant with His people forged at Mt. Sinai fifty days after the Passover, and a mighty gust of wind, the likes of which toppled the Tower of Babel (see Jubilees 10:26), fills the house they are sitting in. The illuminating fire of God multiplies into tongues that rest on the disciples, one on each of the many. As a result their singular speech multiplies, such that peoples of all the different nations gathered for the feast hear the one apostolic preaching each in their own language. Babel isn’t just being reversed; it’s being redone and corrected. Scoffers who observe the familiar pattern, but don’t understand the correction, wrongly accuse the disciples of being drunk, that is, of being in a state of disintegration. Yes, the one is becoming many, but in a way that transmits oneness to the many. The fishermen are being sent out to the many nations in a way that “draws them into a net,” as the troparion of Pentecost describes. Or as the kontakion has it, “When the Most High came down and confused the tongues, He divided the nations; but when He distributed tongues of fire He called all into unity; and together we glorify the most Holy Spirit.”5

Appropriately do the tongues consist of fire, furthermore, because the Holy Spirit’s inhabiting of the disciples is an act of illumination. This is another reason Pentecost is seventh in this sequence despite being the jubilee of Pascha. God multiplies Himself in creation; theosis results, and in the illumination stage thereof (between purification and perfection), man himself participates in this divine multiplication, perceiving the divine logoi in all creation and apostolically converting the many nations to the one God. In the icon of Pentecost, unlike the icon of Ascension, as Jonathan Pageau explains, there is no image of Jesus, and there is no image of His Mother (though Acts does describe her as present in the community of disciples at that time; 1:14). At Pentecost, the many Apostles are now the one Mother of God, the Holy Spirit resting in them and bringing forth the one Body of Christ. The many become one as a result of the one becoming many, but the one that the many become is a one that becomes many! Their henosis is enacted paradoxically in an outward mission into the multiplicity of the world as deified deifiers. So the perfection of theosis already exists within this feast, but it remains to be expressed in its own sequential moment in which the deified cosmos returns to be iconically depicted in the same image as its preceding historical causes, Jesus Christ and the Mother of God.

Η. Sunday of All Saints

So this is the perfection, the octave of the octave. Or the octave of the octave of octave, depending on how you’re counting. All Saints is the octave of Pentecost, counting in days. Pentecost is the octave of Pascha, counting in weeks. The Pentecostarion is the octave of the triadic liturgical year, after the Octoechos and the Triodion.

We get it, All Saints is the octave — and as such, the motion of Pentecost is contained within the rest of the eschaton. Motion and rest, kinesis and stasis (analogous to Matthieu Pageau’s categories of time and space) are both included, but this is how they are ordered in theosis: the ascent of purification at Ascension precedes the descent of illumination at Pentecost, before they together join in the dynamic stasis of perfection on the Sunday of All Saints. At the completion of the Pentecostarion octave, the Body is ascended, the Spirit is descended, and all manner of creation is gathered together as both one and many, both in motion and in rest. The “Lord I Have Cried” stichera of this feast trace the ecclesial hierarchy from “the disciples of the Savior, who became instruments of the Spirit through faith,” to “the armies of martyrs,” who “have filled the Church, which is enlightened by their faith,” to “the divinely wise priests and the sanctified company of honored women,” all of whom “united those of heaven and earth, and by their sufferings received dispassion through the grace of Christ, ... illumining us now like radiant stars.”6

All year round, on each day a list of martyrs and saints are commemorated one by one. Here, on this Sunday, the octave of Pentecost, every holy feast happens at once, those of the saints and those of the Lord. All are present together in one synaxis of praise, worshiping the one undivided Trinity: the unbegotten Father, cause and source of all life, the Son begotten of the Father, who became incarnate and died for us, and rose again, whose Body is distributed to all the faithful, distributed but not disunited, like the Holy Spirit, the Lord, who proceedeth from the Father, whose inbreathing is the perfection of all creation, who is glorified together with the Father and the Son, who hovered over first the waters and later the Virgin’s womb, who spake by the prophets, and who in tongues of fire animates the Body of Christ, the one Christ and Lord who reigns as king forever and ever, the only name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved, amen.

The Pentecostarion of the Orthodox Church, trans. by Isaac E. Lambertsen (The St. John of Kronstadt Press, 2010), p. 94.

Ibid., p. 120.

Ibid., p. 161.

Ibid., pp. 207–8.

Ibid., p. 294. Lambertsen’s translation of the opening participle, “When, descending, the Most High confused the tongues” is needlessly and unhelpfully literal; I’ve amended it according to other versions I’ve heard.

Ibid., pp. 322–23.