The Seven Ecumenical Councils and the Triumph of Orthodoxy, part 2

Yes, they form an octave, but there’s also a strictly chiastic way of looking at it

Read Part 1 here.

I have an alternate arrangement of the Seven Ecumenical Councils to explain, but last time I only got through the first five councils. First I need to complete the octave....

As an Octave, continued

Ϛ. The Sixth Ecumenical Council — Constantinople, 680–681 AD

More time elapsed between the Fifth and Sixth Ecumenical Councils than between any others. A whole, whole lot happened in the seventh century. Have you ever wondered what happened to the Zoroastrians? Have you ever heard of this thing called Islam? Have you ever considered that St. Maximus the Confessor’s writing career overlapped with the final years of Muhammad and the beginning of the Arab Conquest? Looking back at the seventh century, we can see that eventually three major world powers competed for control of the Middle East, and in the end the power that showed up last mopped up the other two and gained long-term dominion over the region, including the patriarchates of Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. But before the Muslims showed up, the Christians and Zoroastrians went at it.

The Roman Emperor Heraclius, with his trusty Patriarch Sergius of Constantinople at his side, thought he was fighting for the empire’s life when the Persians made deep incursions into Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Asia Minor. I mean, they captured Antioch and slew the patriarch, in 614 they conquered Jerusalem and took the True Cross back to their capital, they conquered Alexandria and took control of the Egyptian grain supply, and then they marched deep into Asia Minor, taking Chalcedon in 617, within spitting distance of Constantinople — so you can see where he got the impression that an existential crisis was afoot. Well, at great cost Heraclius paid off the opportunistic Avars and Slavs invading from the north (also a huge problem) in order to concentrate on beating back Persia to the east. He badly needed the cooperation of non-Ephesine and non-Chalcedonian Christians to achieve his aims. The consequences of Christological divisions were destroying the empire. A religious solution had to be found in order to save their worldly kingdom.

First Patriarch Sergius tried the doctrine that said that Christ had one energy — one energeia. It was designed to appeal to Miaphysites in places like Armenia and Egypt, but accidentally its first diplomatic successes were with the Nestorian non-Ephesines in Persia and East Syria. A dialectical synthesis of opposites had been discovered. The prosopic union proffered by the Nestorians (who are conventionally called that, but Theodore of Mopsuestia is more their guy than Nestorius) admitted of there being one energy in Christ, as well as one will — both of which teachings, at least on their face, harmonized with the Miaphysites, who of course were already stressing the one physis. The doctrine that Christ had one energy was the official imperial strategy at the time in the 620s when Heraclius heroically beat back the Persians in a series of legendary campaigns. By 629 Persia was defeated, returned to its original territory, and Heraclius personally restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a lavish ceremony.

In the early 630s, then, Heraclius proceeded forcefully to push Monoenergism (as it’s called historically) on the Miaphysite churches in Egypt for the sake of imperial unity, an ecclesial union the Miaphysites did not wish, and so there was great violence and oppression. At the same time, Orthodox detractors of the doctrine began raising their objections, most prominently a well-traveled Palestinian monk named Sophronius, and his disciple whom he would meet in North Africa, one Maximus, a Constantinopolitan monk who had previously been at a monastery in Cyzicus before fleeing West. When St. Sophronius became the patriarch of Jerusalem in 634, Sergius (still patriarch of Constantinople) bowed to his pressure and, while not disavowing Monoenergism, at least issued a decree banning discussion of one or two energies. To take the place of the fallen heresy, Sergius then sought a new solution and found one in the correspondence of a hapless Pope of Rome (Honorius — included among the anathemas issued by the Sixth Ecumenical Council) who died shortly thereafter, never living to see the consequences of his suggestion and thus never having a chance to repent of it. The new idea, much the same as the old one, was that Christ has one will. Monothelitism was born. This all happened in 634, the same year the Arab Conquest began under Caliph Omar.

No one saw these anti-Trinitarian Ishmaelite monotheists coming, but here they were, an indomitable force making huge gains. By 637 they erased the millennium-old Persian Empire with its dualistic religion off the map for good, and were turning next to Roman lands. Alarmed, Heraclius and Sergius in 638 issued an imperial decree making Monothelitism the law of the land. The same year Arabs occupied Jerusalem: the aged Patriarch St. Sophronius received Caliph Omar, negotiated for the safety of Christians, and died shortly thereafter. In the coming years Heraclius would die, sparking a brief succession crisis, and the Arabs took Alexandria and ruled Egypt (releasing the Miaphysites there from their forced union with Constantinople).

History stagnated from there for a few decades. Heresy was the law of the land in the diminished Roman Empire. St. Maximus mounted a noble defense, finding allies for a time in the see of Rome, as he and Pope Theodore, and after him Pope St. Martin, defied the Emperor and held a local council against Monothelitism, triggering a decade-long schism between Rome and Constantinople. For their efforts Sts. Martin and Maximus were arrested, tortured, and exiled, sent to die in remote corners of the East. A new pope gave in and restored communion with the Monothelites. Eventually in 674 the Arabs lay siege on Constantinople and maintained it for four years before being turned back with the help of newly invented “Greek fire” in 678. Constantinople and environs were secured, but the Levant was lost. In the capital the emperor convoked a council in 680 that condemned the now useless Monothelitism, anathematizing four consecutive patriarchs of Constantinople covering a full fifty-seven years of ecclesiastical rule. Council sessions that spread across nearly a year drew heavily from the work of St. Maximus, especially the local council he and Pope St. Martin held in Rome, but St. Maximus — who was never anything but a simple monk — himself was not named, perhaps to avoid imperial embarrassment.

I take the time to recount the history because Monothelitism, a dialectical synthesis of the preceding Christological heresies, is all about one will, in form and in substance, imperialistically imposing itself on all others. The lesson of history seems to say that believing in such a doctrine is like ceding the territory of your soul to Muslim rule. Meanwhile St. Maximus compiled all the arguments against it. St. Cyril may have said “one incarnate physis”, and St. Dionysius the Areopagite in one letter may have said “one theandric energy” — a phrase St. Maximus can explain within context — but no holy father in all St. Maximus’s searching ever referred to Christ having one will. St. Maximus, does find the teaching in several places among the writings of heretics, however, both non-Chalcedonian and non-Ephesine and all the way back to Apollinaris. That’s a sample of the patristic argument against Monothelitism.

In the positive direction, there are plentiful arguments from reason, from theology, and from Scripture why Christ has two natural wills, not one. St. Maximus is (while not systematic) very thorough, and I won’t be able to recount every point. And a real danger I face here as a Westerner, especially as I try to essentialize things, is looking at the Chalcedonian language and reifying the categories, making semantic equations out of theological formulae while being imperceptible of the realities signified thereby. I’ll try my best briefly to relate the Christological reality, rooted in the one incarnate Hypostasis of God the Word.

That which is not assumed by Christ is not saved by Christ, St. Gregory the Theologian taught contra Apollinaris, who said Christ lacked a human mind — and St. Maximus applied this principle to the human energy and the human will as well. Adam first sinned by will; the will was the first part of him that became sick. Therefore Christ assumes a human will in order to redeem it with the rest of human nature. But then St. Maximus’s heretical interlocutors were constantly and disingenuously confusing the capacity to will, the act of willing, and the object of will. The capacity to will is what the natural will refers to, and Christ must have a human capacity to will and a divine capacity to will, according to His two natures. If this distinction is not made and you say Christ has one will, as though according to His Personal act of willing, what does that say of the Trinity, of which there are three Persons? Are there thus three wills in the Godhead? Or if the one will of Christ is identified as the one will of God, do the Father and the Spirit have a human aspect to their will, or does Christ have no human aspect of His will? And if the latter, what in God’s name is going on on the Cross? Was it God’s will to have tortured to death this anthropicized Person with no anthropic capacity for consent? I wonder, is this not like crucifying an ape? And how is this not just Apollinarianism redux since the capacity for reason and the capacity for self-determination go hand in hand?

In the Garden of Gethsemane, we get an entirely different picture of Christ’s human and divine wills and the way that they are enhypostasized. Natures, we must remember, do not exist as abstract categories, but only in the unity of an hypostasis, a person. In Christ’s case, this is no mere human person, but is the pre-eternal Son and Word of God. His human nature, including His natural human will, is never not operating in a deified mode, ever lovingly submitted to the embrace of the divine will. Many times St. Maximus quotes St. Gregory the Theologian’s Oration 30.12: “The will of [Christ’s] humanity was not set in opposition to God, having been wholly deified.” Therefore in Gethsemane, though the energy of His human will is evident in his natural aversion to death, Christ overcomes human limitations according to the divine energy which is His from before all ages.

For St. Maximus to have understood the pattern of the deification of the natural human will in the one incarnate Hypostasis of the Word of God so as to meet the theological challenges of his day — and moreover to describe it so cogently and so thoroughly — he himself had already to be participating in that deification already. That sanctity is evident in all his writings from beginning to end in his ability to describe the economy of Christ and the means of our participation in it. This, by the way, is why the Sixth Ecumenical Council, vindicating all the Christological teachings of St. Maximus, represents the stigma-position in this octave. Adam’s misuse of his natural will, which the Son of God corrects? St. Maximus can describe how that works, how the fallen will works, how it is different from how Christ’s human will works despite their being the same natural faculty to will, and how that fallen will is then changed to participate in the theosis achieved in the Person of Christ. This is purification, the praxis of the virtues, that preparation which is necessary for all contemplation to take place, and perfection after it.

I have to complain a bit how, in contemporary discourse, the attention lavished on St. Maximus is lopsidedly in favor for his earlier cosmological works in which he at last overturned Origenism after centuries of festering. Indeed this is a remarkable achievement. For years the brightest spiritual lights, like Sts. Barsanuphius and John of Gaza, warned monks to quit Origenist ideas and apply themselves to humbleness of mind. The Fifth Ecumenical Council straight up anathematized Origenism, and still this thymic prohibition was ineffective at stopping the epithymetic excess of monastic contemplation. What needed to happen was for the epithymetic contemplation to be channeled positively in an Orthodox direction instead of just being sternly forbidden. St. Maximus did that. He can’t receive enough credit for that. The whole subsequent Philokalic tradition is unthinkable without this advancement — there are more writings in the Philokalia by St. Maximus than by any other writer, and they’re all from his earlier ascetical, contemplative, and hermeneutical works.

But Fr. Maximos Constas (God bless him, a terrific translator) calls St. Maximus’s Ambigua, where the most anti-Origenist writings are, “undoubtedly his greatest work.” I must demur, no matter how sublime the Ambigua are. To see the solution of a problem four centuries old, when you have copious writings of holy fathers to build upon, is one thing (still an historic accomplishment!). It’s another to meet the challenge of one’s day, when the heretical innovations are fresh, the judgment of the Church is not yet known, and the cost of staring down the tyrannical “one will” of emperor and patriarch is so severe.

St. Maximus’s later Christological works — which shamefully remain without proper English translation — represent undoubtedly his greatest achievement. Read the liturgical services in honor of St. Maximus (celebrated on January 21st and August 12th [transferred from the 13th]): that’s all they talk about. They don’t even mention any of the cosmological ideas. No one ever cut out the Confessor’s tongue or severed his right hand for overturning Origenism. In St. Maximus’s sacrifice of life and limb for the sake of his Christological confession, he comes closest to Christ, the God whom we worship. But nowadays we worship the cosmos, and so we prefer the cosmological writings. Indeed they’re especially helpful in meeting us where we’re at and raising us up, but if we refuse to be raised up and don’t start taking greater interest in the identity of Christ than in the identity of creation, we risk forfeiting our privilege of studying this holy father.

And consider the consequences of not listening to the Christological orthodoxy articulated by St. Maximus the Confessor. Imagine if Heraclius hadn’t pursued a Monoenergistic policy, and the Persian Empire benefited while the Romans had to concentrate on holding the line in Asia Minor. Then when the Muslims rose out of the sands of Arabia, the Zoroastrians would have met them with greater resistance. Those two great powers would have duked it out, and the Orthodox Christians, they who worship the one God in three Persons, would have been the last ones on the scene. There would have been no way to game plan this out, since no one saw the Arabs coming, but heresy is always a choice. Imagine how different it could have been!

Ζ. The Seventh Ecumenical Council — Nicaea, 787 AD

Irony of ironies: when the dialectic of the Hellenistic mind turned on itself once more, finding total sublation in a dangerous new heresy, it was the aniconic, anti-Roman Arab Muslims of Syria that provided the political shelter necessary for St. John of Damascus to write in favor of religious images and against the corrupt icon-fighters ruling Constantinople. But I’ve skipped ahead.

The history this time is simple. In 726, in the general milieu of Islam enjoying much political success, the legend goes that spectacular submarine volcanic activity in the Aegean Sea caused a lot of destruction and scared Emperor Leo III, founder of the Isaurian dynasty, into banning the use of religious imagery in the Roman Empire. Symbolically that’s just what happened: the heresy of iconoclasm erupted like a submarine volcano and caused tsunami waves of destruction and poisoned the environment. Enforcement of the laws against venerating images were at times violent and severe. Many martyrs and confessors suffered in an era that dragged on for sixty years (and that was just the first tsunami). The Roman church in the West never understood why Christians would reject images and never went along with the imperial decrees. Eventually Irene, the widow of Emperor Leo IV, ruling as regent for her underage son Constantine VI, convoked the Seventh Ecumenical Council which restored religious images and defended the veneration thereof.

This is the zeta-council, the sabbath. When you read St. John Damascene’s treatises against the icon-fighters or the acts of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, all the arguments in play seem almost too simple, especially in comparison to the Monothelitism debates of the previous century. “Icons are idol worship!” “No, they’re not. Honor given to images of Christ and His saints passes on to their prototypes.” That’s largely it, seemingly. But in the practice of venerating icons, there exists massive symbolic meaning that recapitulates all Christian cosmology, reflective of all Christian theology.

It is a delightful mystery to me how, in St. Maximus’s identification of the sixth, seventh, and eighth days as a pattern of triadic ascent (see his Chapters on Knowledge), the sabbath symbolizes natural contemplation (theoria physike), or as the Areopagite called it previously, illumination. The sabbath, archetypically, is when God rests — in the Christian story it is when He dies and sojourns in the tomb. Neutrally speaking, death is whenever something higher empties itself into that which is lower. That’s a destructive process when we fallen humans do it, as when we pour our noetic activity into the senses’ preoccupation with seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. But it’s a creative, life-giving process when God the Word gives matter and spirit to His pre-eternal intentions for the creation of the world. When the many logoi — to be identified with the one Logos who is before all being — are given being in life, given being in creation, the emanation is a pouring out from above into that which is lower. It’s the same pattern as when in the center of history the one Logos becomes incarnate: He’s born in a cave because for Him it’s already a sepulcher. This is an image of death, but it’s a life-giving death, a ray of providence from above, one sure to return to God in judgment as an image of resurrection: “Thine own of Thine own we offer unto Thee, in behalf of all and for all.”

On the seventh day God rests from creation because there is a limit to creation, but in that caesura is then visible that which is beyond the limits of creation. God rests from the works that He begins to make, but He does not rest from His works which He does not begin to make — His beginningless energies which shine from before time continue to shine regardless of time. On the seventh day of creation, then, we arrive at the limits of the images of creation in order to peer through them to the divinity behind them, underneath them, above them, within them. The seventh day is symbolic of God’s uncreated energies resting in creation and creation in them. Natural contemplation is the perception of this energetic embrace, and the active participation in it. The illuminated creaturely mind that perceives God in creation, in doing so, is itself animated by the grace of divine energy.

All of which is very hard to attain in spirit — at least the possibility of doing so seems so remote from our lives as we commonly live them. But what isn’t so hard to attain is the act of bowing down before images of Christ and of His Holy Mother and of all the saints, those whom He has made His Body, not by nature but by grace, by adoption. It’s the same pattern as illumination, and by practicing it in our bodies we prepare ourselves to practice it in spirit — already we are joining ourselves to the body of the Church that enjoys such natural contemplation. For when we venerate the saints we worship not their created nature but the uncreated energies of genesis and theosis operating within them. The same goes for all material things through which the divine action of grace is perceived to be working. I use the word “perceive” here in a very pedestrian manner. If any old lady in church “perceives” that an icon of Christ or of the saints is holy, treats it that way, venerates it and kisses it, she is partaking of divine illumination. Icon veneration is the incarnation of the worship of the Incarnate God. All previous proscriptions of graven images — false incarnations of false gods — were to pave the way for the reception of the true Incarnation of the one true God. After all, God Himself was the first to make something according to the Image of God when He made man, the purpose of which is fulfilled when that same Image of God, the Son of the Father, becomes the being that was made according to His own pattern. At that point, we become like Him, and by Him, in Him, and through Him, we make holy objects according to the Image of God.

For through the Incarnation of God the Word, created matter has been used as a vessel for our salvation and for our theosis. When it is put to this use, we revere it, not as it is in itself — and certainly not so as to worship it, as if the power to deify belonged to it by nature instead of by grace — but as it actively participates in God’s pre-eternal intentions concerning it. And all such intentions point to the one divine love of the Holy Trinity, the objective of which love is that that which is made according to God’s image in creation, the human being, in each and every one of its instantiations, be united to God’s nature in the incarnate Person of the Son of God, in the grace-filled power of the Spirit of God, according to the good pleasure of God the Father, and that through the human being (the hypostatic unity of soul and body encapsulating all heaven and earth), all creation is deified. True, deification depends on a strict delineation between that which deifies and that which is deified, and the argument of the icon-fighters rests on distinguishing the Uncreated and the created in order not to worship falsely. But to deny the theotic union of created to Uncreated in the Person of Jesus Christ is to miss the whole point of making the distinction in the first place. It’s to deny the purpose, the activity, the very existence of love.

Papal legates participated in this council, the second of Nicaea in 787, and took great interest in its success. The Pope at the time responded with much relief that the folly of iconoclasm was cast out of the imperial church. However there never seemed to be a full appreciation in the West of the cosmic significance of icon veneration, in light of the hypostatic unity of Christ encompassing all of creation. As art developed in the West after the Schism, the medium was used more as a method of communing with the created world in its own nature, not with any deifying power behind it, underneath it, above it, within it. The practice then turned into a self-deification, as though the artist, through demiurgic powers of perception, were creating the world. Protestants reacted dialectically against this and other Roman Catholic forms of corruption, but without recovering the original meaning of Christian art. Rather they returned to the iconoclasm that Rome reacted against without understanding why. The results have been the same corrupted relationship with the rest of creation, only more utilitarian than aesthetic. Self-deification through the emergent properties of created nature were found more through technology than art, two fields which never should have been so dialectically separated in the first place. This Western approach to the natural world, in both utilitarian and aesthetic aspects, has despoiled our environment. Worse, it has cut off Christians raised in this culture from the knowledge of how to pray, how to receive and interpret revelation, how to participate in the theosis of creation activated by the Incarnation of the Word of God.

Protestant apologist Dr. Gavin Ortlund inherits such a culture, and very recently he partook in a YouTube conversation with Orthodox Archpriest Stephen De Young (also a Dr.) about Sola Scriptura, one which organically gravitated to Ortlund’s explicit rejection of the Seventh Ecumenical Council and the doctrine that honor given to an image passes on to the prototype. In looking at Church history, it would appear, Ortlund asks Protestant questions and receives back Protestant answers. In dialogue Fr. Stephen tried his best to meet him where the Protestant line of questioning led him, but the whole conversation really made me wonder about the liturgical worship of Protestants who hold such beliefs. In any aspect of his life, does Dr. Ortlund bow down to anything? I mean, physically bow down? The Greek word for veneration, proskynesis, meant bodily bowing down to something. St. John Damascene explained the action as a simple expression of humility before a superior, with multifarious forms of use in the life of a human being, not just worship of God. I’m sure Dr. Ortlund would perform mental gestures of humility before others, granted. But does he ever do it in his body?

On the website of the organization his church is affiliated with, there are various religious images — photographs, deployed for the utilitarian purpose of conveying information. Here is an image deliberately chosen for the website so as to deliver the information of what it is like to engage in communal prayer as a Reformed Christian:

They’re standing (that’s good)... in front of a black curtain.... Why are their eyes glazed over like that? Like Bronn in Game of Thrones when he’s “warging”? It’s like their bodies are all facing something that their minds are not allowed to look at because any form of obeisance in the body can only be construed as idol worship. Honor paid to images, so they are taught in doctrinal content and liturgical form, cannot pass on to prototypes. So what happens when the band stops and the preacher takes the podium and commands their bodily attention with the spoken word of God? Well, they sit down, I suppose, as though in judgment of the word they are receiving, the opposite of proskynesis.

This very modern attitude, which like death divides the natures of soul and body in the face of hypostatic unity, is projected by Protestants like Ortlund back onto the ancient world — not just onto the Gnostics or the Manichaeans where its closest analogues could probably be found, but onto the ancient Church which believed in the resurrection of the body and the oneness of eternal life, breath and dust united hypostatically, as God intended. No, to reject Nicaea II as a Christian is to cut oneself off from the divine illumination offered to us in the Body of the Incarnate Lord, and why? Historically it was for the sake of imperialistic control over the material world as a path to self-deification. That pattern persists. Not in the Orthodox Church, though.

Η. The Triumph of Orthodoxy — Constantinople, 843 AD

Twenty-seven years after the Second Council of Nicaea, in 814, the imperialist impulse to impose the human will on creation overcame the Empire again and initiated a new tsunami of iconoclastic destruction. But thirty years later, the Sunday of March 11, 843, the first Sunday of Lent, a procession was held in Constantinople restoring images to the churches and announcing the Triumph of Orthodoxy. It was St. Theodora — again a widowed wife of an iconoclast emperor serving as regent for her underage son — who championed the holy icons. Her reforms were embraced by the Church and stuck, kept alive each year liturgically on the first Sunday of Lent as the ritual imprint of an eternal victory over not just iconoclasm but all heresy.

Iconoclasm can be seen as the recapitulation of all heresy in the way that it denies the Incarnation and repeats the fundamental Arian error on a cosmic scale. For as Hebrews 1:3 has it, the Son of God is the express image (in Greek, χαρακτήρ, an imprint, a representation) of God the Father’s substance (hypostasis, not yet a Chalcedonian usage of the term) and the brightness of His glory. For those participating in Orthodox theosis, this relationship denotes a consubstantiality of the Son with God the Father. But Arius moved the line between created and Uncreated — between that which is deified and that which deifies — between the two Persons, such that the Son of God could no longer of His nature have the power to deify, but Himself would be subject to deification from the Father.

Well, if the Son and Word of God is the Image of the Father (according to which we are made), and the iconoclasts are to be believed that honor paid to an image does not pass over to its prototype, then the first two Persons of the Trinity once again must not be very consubstantial, honor paid to the Son being unable to reach the Father.

But iconoclasts were primarily arguing that honor paid to created images does not pass over, ultimately, to the uncreated Prototype, to God the Word. It’s as if to say the Incarnation isn’t real and the hypostatic unity of Christ fails to bridge the unbridgeable gulf between created and Uncreated — which again would make sense if you believed along with Arius that the Son’s begetting means He was made and isn’t Uncreated. But all of this is contradictory nonsense that completely fails to explain the majesty and power of the Gospel.

Anathema to all of it, says the Triumph of Orthodoxy. This is the octave, the eighth day, when the whole cycle of heresy is overcome and eternal peace is beheld, in type. There were still heresies after this; this was not the end of sin among the Roman Christians. But when moral and theological falls occurred, the consequences were different because the stakes were different. It was a different phase of life. After this point in history, the form and content of the Seven Ecumenical Councils was no longer in doubt in the Roman Empire, which only now, five hundred years after Constantine, could finally be thought to have converted to faith in Christ. Only now, for example, was Romanized Hellenic culture mature enough to reproduce its faith in others, as with their Slavic neighbors to the north, starting with the mission of Sts. Cyril and Methodius to the Bulgarians in the ninth century and culminating in the conversion of the Kievan Rus’ in the tenth century. The Russkies have been the most prominent cradle-born Orthodox Christian civilization, but their Roman mother enthroned in Constantinople was only able to bear them once she came of age.

The process of that maturation is octave in shape, as numbered by the Ecumenical Councils and perfected by the Triumph of Orthodoxy the way an eighth day crowns a week. Other councils in the Orthodox tradition have at times been called ecumenical, such as the Fourth Council of Constantinople in 879–880 vindicating St. Photius the Great (imperial politics got really nasty in the ninth century, as St. Theodora’s son Emperor Michael III was not a healthy Christian) or the Fifth Council of Constantinople in the 14th century vindicating St. Gregory Palamas and the Hesychasts. But neither in liturgical memory nor in symbolic consciousness are they numbered with the others because they don’t participate in the same cycle, even if they both are of great authority.

The Roman Catholic Church, or course, kept counting, and their latest, Vatican II in the 1960s, is numbered the Twenty-first Ecumenical Council. That would be the sabbath of a third week of councils, if the octaves overlap. I’m not so familiar with these councils, only where they collide with Orthodox history (the false union of Florence counts for Catholics as the Seventeenth Ecumenical Council, the chi-position of what would be the third octave) — but I’m curious to know if they fall into the pattern of naturally occurring octaves. If so, it would not be recency bias to think their next so-called Ecumenical Council, as the octave of the third week of councils, would be of extreme historical importance. But the octave shape isn’t a sign of sanctity, as I think I fully demonstrated in my articles on American politics; it’s just a natural pattern in which things happen, both good and bad. The Eighth Ecumenical Council for Roman Catholics, that which supposedly crowns their first octave, was decided in retrospect after the Schism to be the earlier Council of Constantinople in 869–870, the one that anathematized St. Photius the Great. Though I normally talk about the eighth day in terms of the heavenly kingdom, it’s important to remember that it’s not experienced so fondly by those who haven’t prepared themselves to do so. But the shape naturally occurs, for good or ill. Accordingly, it’s not so significant that the Seven Ecumenical Councils honored by the Orthodox Church are in this pattern, so much as it is significant that this particular cycle of councils is the instance of the pattern that the Church chooses to honor. I do think it is significant, however, that, unlike others, the Orthodox Church in her sagacity does have a liturgical and symbolical awareness of how the cycle works.

As a Seven-branched Candle Stand

The reading is from the prophecy of Enoch, seventh of Adam (1 Enoch 24:2–4):

And I proceeded beyond them, and I saw seven glorious mountains, all differing each from the other, whose stones were precious in beauty. And all (the mountains) were precious and glorious and beautiful in appearance — three to the east were firmly set one on the other, and three to the south, one on the other, and deep and rugged ravines, one not approaching the other. The seventh mountain (was) in the middle of these, and it rose above them in height, like the seat of a throne. And fragrant trees encircled it. Among them was a tree such as I had never smelled, and among them was no other like it. It had a fragrance sweeter smelling than all spices, and its leaves and its blossom and the tree never wither. Its fruit is beautiful, like dates of the palm trees.

So we are introduced to the prophetic image of a sevenfold chiasmus, in this case a range of mountains bending at an angle from east to south, the pivotal central mountain being tall like a throne and home to a tree mysterious and beautiful to behold.

Of course, the most famous sevenfold chiasmus is the menorah in the Holy Place of the Tabernacle, described in Exodus 25:31–40. There are ancient depictions of the one later used in the Temple at Jerusalem, such as on the Magdala stone:

This chiastic pattern of arranging groups of seven is of unimpeachable prophetic origin, and it remains in use today in Orthodox Christian worship, with seven-branched candle stands patterned after the Tabernacle menorah commonly found directly behind altars.

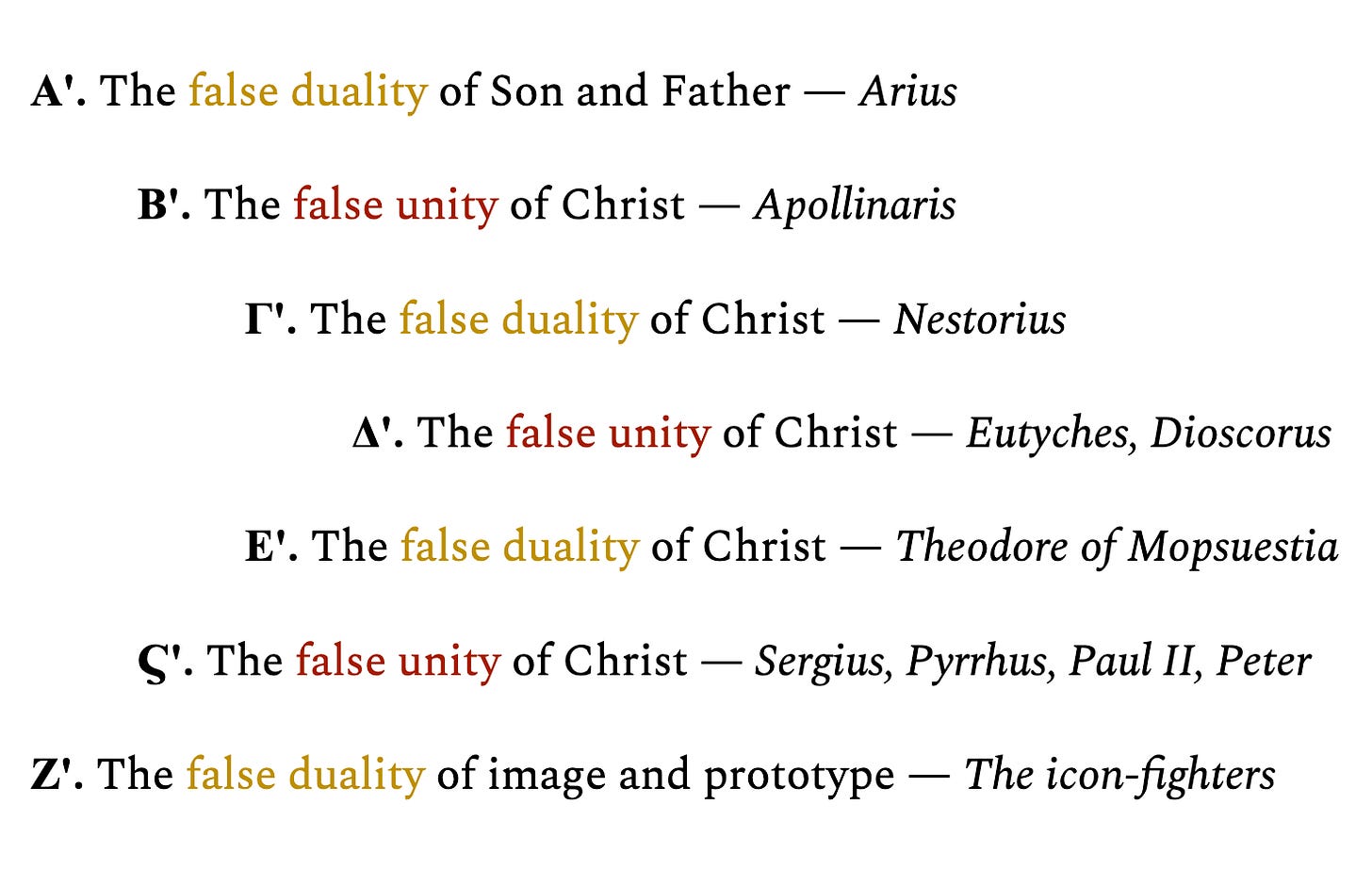

So I would be remiss not to note the ambiguity of form in regard to the Ecumenical Councils. With careful consideration I do find the week-shaped octave pattern, such as I took pains to describe it, the more meaningful lens through which to view this history, but the chiastic heptad has much to recommend it and is worthy of contemplation as well. Here is the outline indented chiastically, but using for labels plain Greek numerals:

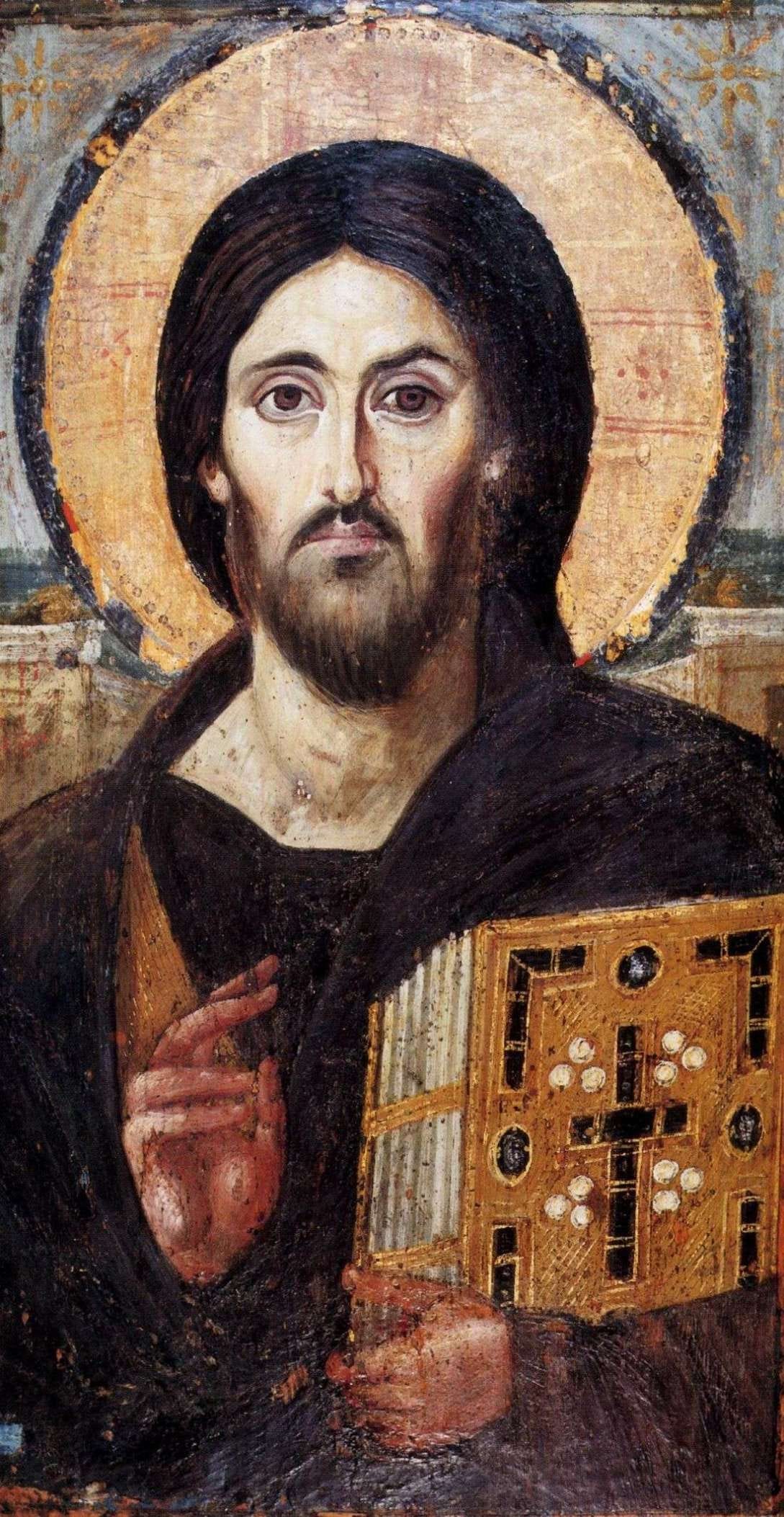

Oddly enough, the Seventh Ecumenical Council had not originally planned on returning to Nicaea. It was first called in Constantinople in 786 but was disrupted by iconoclast soldiers. The following year a diversion was created for the soldiers, and the council successfully met in Nicaea instead, thus creating a handsome geographical inclusio to close the conciliar cycle. More meaningfully, the parallel between Α'. and Ζ'., the two councils of Nicaea, compares the total deity of the Son, consubstantial with the Father, to the total Incarnation of the Son, effecting the deification of all creation as testified to in the veneration of icons. Symbolically, Arianism is the fount of all heresies, and iconoclasm is their cosmic consummation.

One more layer in, the Second and Sixth Ecumenical Councils (Β'. and Ϛ'.), the first and third of Constantinople, represent the perfection of Triadological and Christological dogmata, respectively. And Apollinarianism and Monothelitism parallel each other very cleanly. Reason and self-determination, the philosophers tell us, go hand in hand. Well, Apollinaris denied Christ a human mind, and the Monothelites in effect denied Christ a humanity capable of self-determination. The same argument of St. Gregory the Theologian, that that which is not assumed in Christ is not saved, solves both crises.

If those two heresies are so similar, it is because the dialectic generating them is symmetrical, as evidenced by the three central councils. Here in this model, relative to the octave pattern, the middle shifts from the Third to the Fourth Council, Chalcedon. At Chalcedon (Δ'.) we find a theological crossroads between person and nature, between the unity and duality of Christ. In harmony with Triadology, hypostasis is used for the oneness of Christ, physeis for the duality — “one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only-begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably.” Here the teachings of both Sts. Cyril of Alexandria and Leo of Rome are accepted without need for dialectical synthesis, because it’s recognized they’re already pointing to one and the same Christ.

On either side of Chalcedon are councils dealing with adjacent and symmetrical Christological issues. Whereas Ephesus (Γ'.) emphasizes the unity of Christ, anathematizing Nestorius, Constantinople II (Ε'.) does the same, anathematizing Theodore of Mopsuestia — but it’s a unity emphasized in the light of the Chalcedonian definition. These three central councils go together as a chiastic triad of responses to dialectical heresies. And you can see here below how the heretics combatted by all Seven Councils follow a dialectical chain that comes full circle:

Orthodoxy is not just the arbitrary doctrine of history’s winners. It is faith in the Holy Trinity which can only be known through the divine revelation of Pentecost and is passed down through the Church by means of Holy Tradition, understood as the life of the Holy Spirit. The heresies anathematized by these Spirit-guided councils were all sourced rather by rebellious humans, who generated their knowledge rather by means of dialectical thinking — which cannot help operating according to an historical pattern of reaction and counterreaction. At every turn in the dialectical chain, the Holy Spirit delivered the Church from the heretics’ atheist madness so as to transmit the divinely sourced faith whole and unharmed to a new generation. “The generation that cometh shall be told of the Lord,” the Psalmist says, “and they shall proclaim His righteousness to a people that shall be born, which the Lord hath made” (Ps. 21:31). Yea, “Let this be written for another generation, and the people that is being created shall praise the Lord” (Ps. 101:18). So praise the Lord, people!

The Same Ambiguity of Structure Seen in the Jesus Prayer

In case anyone thinks my identification of an ambiguity of structure in the sequence of the Ecumenical Councils “disproves my thesis” or “reveals my methods of contemplation to be an arbitrary projection of form”, or some other such left-brained criticism I can imagine being leveled, let me at least quickly show how the same shape — with the same ambiguity, though I much prefer the octave — is discoverable also in the Jesus Prayer at the heart of Orthodox spirituality. The full form of the prayer, in octave format, is as follows:

The pattern of the cosmic chiasmus is plainly evident in the fivefold address “Lord Jesus Christ Son [of] God.”

The name Lord (Α.) implies the hierarchy of creation. The human name Jesus (Β.) calls to mind the human story of Israel from which Jesus comes forth. The name Christ (Χ.) indicates an anointed Savior liberating His people from the bonds of death, whose royalty merits centrality. The name Son (Ο.), unique to the Second Person of the Trinity, yet typifies the relationship with God to which the Church is called, as with the prayer “Our Father.” The name God (Ω.) portends the theosis to come; it stands for Him whose identity suffuses all creation in the judgment, when all things are put in order and everything is God’s.

“Have mercy on” (Ϛ.) — one word in Greek, ἐλέησον — initiates a triadic phrase following the pentadic address. The mercy part of the triad is for purification purposes.

The “me” part (Ζ.) is the black hole of unworthiness on which the plea pivots, the tomb into which we’re inviting our Lord; “me” is the impression made according to the image of God, which is ripe to be made over in His likeness by the ignition of His energies.

And as for why “τὸν ἁμαρτωλόν”, “the sinner”, is worthy of the eight-spot (Η.), this is the most wondrous mystery of all. I would have to strain all my spiritual muscles in order to try to explain it, but fortunately Dr. Timothy Patitsas has already done it, as if writing my commentary directly for me (and better than I could do it).

I’ll get to that, but first let me address the article “τόν”. Greek articles aren’t like English articles. The language doesn’t have an indefinite article (“a/an”), and the article that it does have doesn’t function exactly like the English article “the”. There is a sense to what the article’s presence or absence means, but it’s native to Greek and is only gleaned from context. It’s definitely more “the” than “a”, but there’s no single way to translate it. The “τοῦ” before “Θεοῦ”? That’s an article. It has meaning in Greek, but if you said “Son of the God” in English, you wouldn’t be conveying that meaning any better, certainly not enough to make the awkward expression worthwhile.

The “τὸν” in “τὸν ἁμαρτωλόν”, however, is more of a difference maker. Again, Greek articles don’t function according to the definite/indefinite dichotomy of English articles. “Me, a sinner” is not a bad translation; it carries a lot of the original meaning. But there’s a lot to be said in favor of “the sinner,” especially when it comes to perceiving the phrase’s more mystical meanings. This is where Dr. Patitsas comes in. Challenged to explain the usefulness of finishing the Jesus Prayer with self-identification as a sinner, he first gives the two responses that conform to aesthetic and moral reasoning (Beauty and Goodness): there’s a recognition of our creatureliness, of our proximity to the non-being from which we came, and thus of our dependence on God, and then there’s a confession of actual sinfulness, of having behaved badly. “But most importantly of all,” he writes, there’s a deep mystery that accords with the Truth that epitomizes both Beauty and Goodness:

By calling ourselves “the sinner,” we willingly identify ourselves with Christ who “became sin” for the life of the world (II Cor. 5:21). Christ’s expiation of our sin consisted in his willingness to take all human sin upon himself. The result was that He conquered death, and was seated in glory at the right hand of the Father. He was willing to die as if our sin were his fault. It is this that makes him our Savior.

Heaven is the place where everyone has become willing to be lost for the salvation of the other. Hell is the place where no one is so willing. Pronouncing ourselves “the sinner” is what we do when we share in Christ’s readiness to give his life for the life of the world. In fact, calling ourselves the sinner may not have much to do with how many sins we’ve actually committed.

When we don’t make ourselves lower than the worst by seeing ourselves as the sinner, then we are denying Christ — and denying him at the precise moment, his crucifixion, when such a denial would be most hurtful to him. On the cross He “became sin” so that there his anointing as the Christ was the most costly and the most perfectly revealed, though in a hidden fashion. If we would be saved by his Cross, we must try to unite ourselves to him when He is on the cross.

He explains further,

Notice that on the cross Christ didn’t call us sinners, but instead He claimed that we were innocent, even as we crucified him. “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do” (Lk 23:24). There is only one “Sinner” in his universe at that point. I think this will help us see in what way “the sinner” of the Jesus Prayer is Christ himself; it isn’t referring only to you because you have done wrong. It is also referring to Christ who, though blameless, was willing to let sinful human beings condemn and punish him as a sinner, for the life of the world. You call yourself “the sinner” because He is your Bridegroom and you want to be one with him, especially there on the cross where He poured out his life for all mankind.

When you recite the Jesus Prayer, you unite yourself to him who became sin for the life of the world. You join yourself to his person by entering into his act of self-emptying love for the entire world. This journey to perfect oneness with Christ is fulfilled when you call yourself by his “assumed name” — the sinner. Don’t shy away from this part of the prayer — it’s the answer to the first part, the calling upon Christ for mercy.1

I love most of all how the Jesus Prayer looks through the lens of the octave, but I also recognize its fittingness as a seven-branched candle stand. The symbolic eighth is not numbered among its elements but is present throughout, as though it is the single fire lighting all the lamps, or the unmentioned occupant of the central throne among Enoch’s seven mountains. Again, here is an outline indented chiastically, but labeled with plain Greek numerals:

What we just read about “the sinner” (Ζ'.) makes for a compelling compare/contrast partner with “Lord” at the beginning (Α'.). The juxtaposition of “Jesus” and “me” (Β'. and Ϛ'.) draws the necessary distinction of hypostases. “Christ” (Γ'.) means “anointed”, and, well, patristically and hymnographically the Greek word for mercy (Ε'.) is commonly associated with oil because the two words sound the same. Poetically, to ask for mercy is to ask to be christened with oil.

In the central “Son of God”, meanwhile (Δ'.), there is, secondarily, a reference to the role extended to us through the promise of adoption. But primarily there’s an implicit invocation of the three Persons of the Holy Trinity. The name Son implies a Father, and as the Holy Apostle Paul says, “No one can say that Jesus is Lord, but by the Holy Spirit” (1 Cor. 12:3) — the same would apply, we can assume, to calling Him the Son of God.

The Holy Trinity as revealed in the Person of the Son of God is, like the eighth day, the intended occupant of the throne on that central mountain, taller than the surrounding six, the one with that tree, beautiful and strange, and full of good fruit. The Holy Trinity is the love that makes everything sweet, the love that makes everything possible. Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, the sinner.

Timothy G. Patitsas, The Ethics of Beauty (St. Nicholas Press, 2019), pp. 62, 63.

Thank you Cormac!

Have you ever read a commentary on or contemplated the relationship between the three powers of the soul and the three transcendent categories of truth, goodness, and beauty? Would love to hear your insights