The Seven Ecumenical Councils and the Triumph of Orthodoxy, part 1

Yes, they form an octave...

Octaves just happen. They’re a natural pattern. As with weekly cycles, as with musical scales, as with heavenly bodies — as with human teeth (something fun I hope to write about eventually) — so with some historical processes. The premise of the Book of Jubilees is that history transpires in such a form, a jubilee being a week of weeks plus one. The Apocalypse of Weeks in 1 Enoch and the genealogy of Christ in Matthew seem to suggest biblical generations proceed according to a heptatonic pattern, which I wrote about recently. I also last fall wrote about how American political history is shaping up as an octave, something it might have in common with Russian history.

Well, the story of the Roman Empire’s conversion to the Christian faith also appears octave in form. The Seven Ecumenical Councils, from the fourth century to the eighth, chart the Church’s response to the cycling of the Hellenistic mind through the full gamut of heretical error in type. The development of heresy is a dialectical process with — typologically speaking — a beginning in the Arian response to the imperial embrace of Christianity, and an ending in iconoclasm, which serves as a recapitulation of all heresies. Of course there were heresies before Arianism and after iconoclasm, but the historical process between those two points is symbolic of the whole.

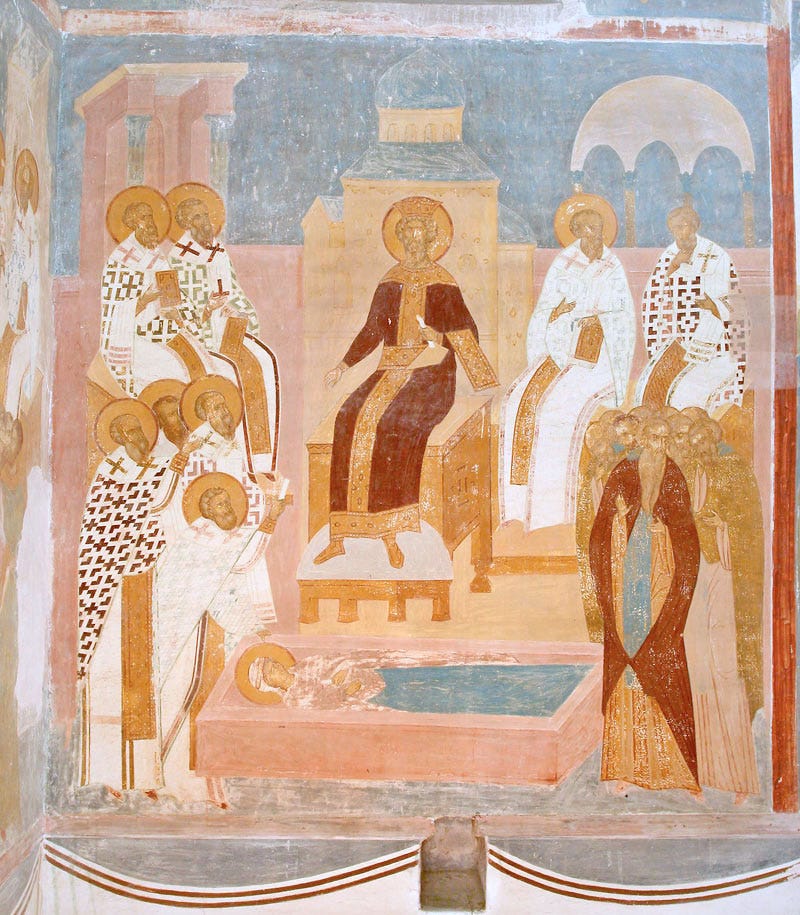

Alas, the Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787 may have rejected iconoclasm, but it didn’t end it, which after a spell returned to power as fiercely as before. The act of finally putting a stop to the madness fell to a council in 843 that was of ecumenical import but was not numbered among the Ecumenical Councils. This was the Triumph of Orthodoxy, which restored the icons by way of an ecclesial procession in the imperial capital on the first Sunday of Lent, on which day in the liturgical calendar it has ever since been commemorated in recognition of the Church’s eternal victory over dialectical ignorance. Though the Roman Empire began its collective conversion in the fourth century, not until the ninth, a full five centuries later, could it be said that Orthodoxy had at last triumphed over her rambunctious mind. The process is heptatonic, with the Triumph serving as the octave — though, with ambiguity of form, it can also be contemplated according to a familiar sevenfold chiastic shape.

As an Octave

Α. The First Ecumenical Council — Nicaea, 325 AD

The First Ecumenical Council established the pattern of the cycle. An ecumenical council is convoked by a Roman emperor in response to divisions in the Church. The state is like the body, and the Church is like the soul. When a Christian emperor does this, therefore, and the bishops comply, it is like a person bringing himself body-and-soul into church at a time of spiritual confusion and distress in order to be healed through prayer and sacraments. So a council is convened. Hundreds of bishops confer and, following the pattern of the apostolic council at Jerusalem in Acts 15, issue decrees to all the churches — “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit, and to us...” (Acts 15:28) — that are then enforced by the emperor in all his territory. Body and soul are thus made whole through the action of the Spirit.

In 325, overwhelmingly the most pressing issue was the teaching of the Alexandrian priest Arius that the Son of God is in some sense subsequent to God the Father in being, that “there was a time when the Son was not.” This teaching was roundly rejected by the bishops of the council, who numbered 318 even as did the army of Abraham, the founding father of faith in God, as recorded in Genesis (at 14:14). Believing in the Son and Word of God’s consubstantiality with God the Father is therefore foundational to the faith. The resulting creed stated, “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty,” and “in one Lord, Jesus Christ ... consubstantial with the Father.” God the Father is the “maker of all things visible and invisible,” yet the Son is “begotten, not made, ... by whom all things came into being.” The creed also added, “[We believe] also in the Holy Spirit,” but did not elaborate. The fathers of the council thereby affirmed their belief in the Holy Trinity, but were eager to say only what was necessary at the time to defend it. The Christian Church is still a mystery religion, and is careful about what it tries to articulate in earshot of the uninitiated.

This council also took pains to set standards for the dating of the Christian Passover, the Pascha. It was to be on the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the vernal equinox. Before this time, dating methods varied in different parts of the world according to different apostolic traditions which were further complicated by fragmented Jewish methods for lunar reckoning. But the death and resurrection of the Savior is a singular event that the Church seeks annually to enter with a unity of liturgical worship. This praxis goes hand in hand with the dogmas of the faith.

Β. The Second Ecumenical Council — Constantinople, 381 AD

The First Ecumenical Council may have overcome Arius, but, historically, it did not overcome Arianism, as the Hellenistic mind proved very resistant to Orthodoxy. Dialectic thinking, when it overcomes theological perception, can conjure all kinds of wrong combinations concerning the identity of Jesus the Christ and His Father, and the fourth century was a time in which they were all brought to light — and the Holy Spirit submitted to the doctrinal chaos as well. For several decades on end, those whose passionate minds distorted the truth about the Holy Trinity occupied the highest offices in both church and state.

Eventually the spirit of fallacy, running on the steam of perishable thoughts, lost out to the eternal faith of the Apostles, of the martyrs, and of the monastics flooding desert places throughout the fourth century. This is still the story of the apostolic Church overcoming the Roman Empire, as indicated in the writings of the New Testament, and it will remain so for centuries to come.

So we come to the first council of Constantinople, which was instigated not only by the need to bring semi-Arians to the light of truth, or the need to refute the heretics who subordinated the Holy Spirit relative to the Godhead, but also by a new heretic Apollinaris who was teaching, in dialectical opposition to Arianism, that Jesus’s mind was provided by the divine Logos and was not human. All these monstrous distortions of how love works were rejected in favor of the apostolic faith, and an expansion of the Nicene Creed was drafted. This new Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed — confirmed as the Symbol of Faith by later councils starting with Chalcedon — operates like a torah descending from Sinai and forever symbolizing the Church’s identity as a people called apart for the worship of the Holy Trinity. The wording is designed for the purpose of erecting a firewall against heresy, such that the Son is not just the only-begotten of the Father, but is begotten “before all ages,” so that no one can deny His unity with the Father, nor the equality of worship due to Him. Likewise, the Holy Spirit is identified as “the Lord, the maker of life, who proceedeth from the Father [John 15:26], who with the Father and the Son is together worshiped and glorified, who spake through the prophets.” God is the source of life; life, for us, is to be connected with God. If the Holy Spirit is the life-maker, or the life-giver, as it is often translated (τὸ ζῳοποιόν), He is the one who connects us with God, who “spake through the prophets.” But in order to be the giver of life, He has to be the maker of life; He must be the source of life, God Himself. If the spirit animating you is less than God, then you cannot be connected with God, and you can have no life in you. Then God’s love for us is not consummated, and there is no love — and there is no God.

These are the stakes to our worship and the purpose to the dogmatic firewall protecting our faith. Those who adhere to the Symbol of Faith as drafted by the Second Ecumenical Council are set apart by the Triune God as the people of God — as the “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church” differentiated from the world by “one baptism for the remission of sins.” And this kingdom shall have no end. To the articles concerning Jesus Christ the Son of God was added the line, “of whose kingdom there shall be no end,” no telos. There is no telos external to the kingdom of Jesus Christ the Son of God, because the kingdom of Jesus Christ is the telos, because Jesus is God. For those Hellenes still dripping with Gnostic tendencies, whose teleology had been poorly configured by broken ideas, it was added at the end, “We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the age to come, amen.”

In a sense, the protection of Trinitarian theology was accounted for by this point. The orations of St. Gregory the Theologian, who for a time chaired the Second Ecumenical Council as the patriarch of Constantinople, remain standard expressions of the faith; their wording is often lifted verbatim for use in Church hymnography. Authoritative treatises on the Holy Spirit had already been written by the likes of Sts. Athanasius and Basil the Greats (both of whom reposed in the 370s less than a decade before the council) and merely required wider approval and acknowledgment from those in power. The anti-Arian heretic Apollinaris, meanwhile, one-time cohort of Sts. Athanasius and Basil, despite being condemned at the Council of Constantinople, broke new dialectical ground in Christological heresy by denying Christ a human mind. He was a trailblazer, a real red-figure revolutionary for the mindless who adore their own minds. Going forward, the meaning of the Incarnation and how it is to be understood will be all the rage.

Ξ/Χ. The Third Ecumenical Council — Ephesus, 431 AD

Apollinaris, in opposing Arianism, overstated the unity of Christ’s humanity and divinity to the detriment of both. In his horrendous formula, Christ’s humanity is a mindless puppet incapable of volition, and the divinity who created it comes off as a monstrous, loveless Svengali from whose creation nothing good can come without overriding force. Such doctrines of Christology are reflections of their teachers’ relationships with God; if the Gospel commandments are followed as they should be, a proper understanding of how love works is attained, and such heresies do not result. A similar problem in the opposite direction occurs with the heresy of Pelagianism espoused by Celestius of Rome and North Africa.

Foremost disciple of Pelagius, Celestius, rather than stripping man of his volition, overemphasized its prowess, eliminating the need for God’s grace to deify us beyond our inborn nature, which in our current state inherits no corruption but is as it was before the fall with no modal difference. Baptism is not necessary “for the remission of sins.” Such teaching amounts to a Luciferian self-deification that knows no humility or obedience and is insensitive to the pain of corruption in this fallen world because it is without love.

The Third Ecumenical Council, held at Ephesus in 431, accordingly anathematized Celestius, but that was mere background to the main reason the Council was called. Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, thought himself clever in answering the Christological uncertainty of his day by refusing to refer to Jesus’s mother Mary as Theotokos (“bearer of God”) but only as Christotokos (“bearer of Christ”). God, he reasoned, is beginningless and cannot be born. God cannot suffer or die. The ramification of his position was basically that God could not be incarnate. Jesus may have been God, and Jesus may have been man, but in Nestorius’s eyes the union of the two natures was that of a loosely bound persona. I think of it as a man and a woman staying in a house together, but not sharing a bed and otherwise having nothing to do with each other, leading completely separate lives.

Nestorius had as a fierce opponent to his teaching that great lover of truth St. Cyril, patriarch of Alexandria, who stirred up much controversy against him. It was actually Nestorius’s idea for the emperor to convoke a council, expecting that it would exonerate him and bring peace to the empire. As politically assertive as he was theologically literate, St. Cyril prevailed though, and the council anathematized Nestorius, which the emperor eventually accepted.

St. Cyril taught that in Christ was formed a union of divinity and humanity, what he called at the time “one incarnate physis of God the Word.”1 The phrase was meant as a paradoxical expression appropriate to the mystery of the Incarnation, much like “Theotokos.” How could God be born? How could there be one of anything that is both God and incarnate, two eternally disparate things? What was meant by the word physis, however, was not clear to all listeners. As with many Greek theological terms at the time, its definition was yet fluid, as vocabulary was just then being molded to describe what had never been described in Greek before. St. Cyril used it according to a sense that was falling out of fashion by his day; he meant something like a concrete reality or instantiation — that which hypostasis was already coming to mean (another word in the midst of theological transformation). But physis was understood by many contemporaries, including Nestorius, as what we now understand as nature, the sum total of attributes of something. Compounding the problem, St. Cyril thought that in using the phrase “one physis” in regard to the unity of Christ, he had as precedent his hero and predecessor St. Athanasius. It turns out the relevant text was falsely attributed, though, and was actually by Apollinaris, to whom Nestorius was dialectically opposed. Indeed, Nestorius mistook the Cyrillian emphasis on the unity of Christ as Apollinarian and accused it of being such. In context, though, no one could possibly think St. Cyril’s teaching admitted Apollinarianism. But Nestorius was not nearly so astute, nor was he humble enough to recognize a superior theological mind. If he had venerated the Mother of God as he should, it bears mentioning, none of this likely would have been a problem.

As it happened, around the time of the Council of Ephesus, St. Cyril would begin using the word hypostasis to express the unity of Christ in place of physis (see his Third Letter to Nestorius), but in context (and St. Cyril was a voluminous writer, so there was plenty of context) it was plain that his meaning was the same. What we have since understood as hypostasis, a self-subsistent concrete reality, is what St. Cyril always meant — a person, if you will. “Person” is what we would say in English now, but then our idea of personhood is entirely conditioned by this very history of Christian theology. The Latin root persona, and its Greek equivalent prosopon, did not before Christianity have the sense of permanence and self-subsistence that hypostasis brings. A persona/prosopon indicated rather an identity that exists in relation to others, like a face that exists in the perception of others, not necessarily existing of itself — and that is how Nestorius characterized the unity of Christ, as prosopic. (For this use of the word prosopon for the oneness of Christ, he had as precedent his teacher Theodore of Mopsuestia, a figure even more influential than himself, who will become more relevant later on.) The image of Christ that results from this dialectically anti-Apollinarian heresy is of someone who is not substantially one but divided between two hypostases, divine and human. This is not an image of love, but of death. Death we understand on the earthly plane as the separation of soul and body. Spiritually, it’s the separation of God and man, which is caused entirely by the volitional deviation of man — there’s a reason Nestorianism was paired with Pelagianism at this council. Both effectively celebrate death and spurn Christ’s victory over it.

The Council of Ephesus’s victory over them by proclaiming what the Church would soon understand as the hypostatic unity of Christ is why it merits the central Ξ/Χ-position in the sequence. Until now I’ve been content merely to imply the octave pattern’s presence in the history of the councils. The Council of Nicaea (Α.) is foundational to the form, and the First Council of Constantinople (Β.) represents an exodus from ignorance into the Trinitarian faith. Ephesus (Ξ/Χ.), through the diligent theologizing and rigorous politicking of St. Cyril, typifies the resurrection of death by the grace of God achieved in the lives of faithful humans. I’ll be more deliberate in making connections going forward, now that I’m passing the pivot point of the octave’s pentad.

Ο. The Fourth Ecumenical Council — Chalcedon, 451 AD

St. Cyril, in his faithful transmission of the patristic Christian religion amidst a sea of adversity, achieved a victory over the death that is heresy, and thus brought forth a new image of the Resurrection of Christ in history. After his death in 444, however, it would take similar efforts for a new generation to achieve the same victory and proclaim the true faith regarding the Incarnation. And the crisis occurred almost immediately because the lack of clarity of expression was so abundant among the different corners of the empire — as evidenced by St. Cyril’s own pivot to using hypostasis instead of physis to name the unity of Christ after the Council of Ephesus.

So there was a second council of Ephesus, in 449, and it went very poorly. Eutyches was the archimandrite of a monastery outside Constantinople. In dialectical opposition to Nestorius, he fell into the opposite error of overemphasizing the unity of Christ at the expense of not protecting the duality of Christ’s consubstantiality with both God and men. For all his opposition to Nestorius, Eutyches seemed to interpret St. Cyril’s phrase “one (mia) physis” in a way not sufficiently different from his nemesis, just in the positive instead of the negative. As this archimandrite of some influence was vocal about his opinions, St. Flavian the patriarch of Constantinople called a local council in 448 and had Eutyches deposed. St. Cyril’s successor as patriarch of Alexandria, Dioscorus, came to Eutyches’s aid and convinced the emperor to convoke a new council — not just a local one, but ecumenical. So one hundred thirty bishops gathered at Ephesus.

Pope St. Leo of Rome got involved in this one, supporting St. Flavian and siding against Eutyches. He did not attend himself (no Roman pontiffs ever attended these councils) but sent a letter that has since been called the Tome of St. Leo. It was written in Latin, and it exhibited a linguistic and philosophical sensibility foreign to the debate that in the East was occurring in Greek. Since it emphasized the two natures of Christ, it was poorly received by Dioscorus and the Miaphysites, as we might as well start calling them (mia = one). Dioscorus chaired the council and deliberately avoided reading the papal Tome. Eutyches was exonerated, and St. Flavian was anathematized. When the sentencing occurred, an immense, angry mob attacked St. Flavian, ripping him from the altar to which he had fled for safety and beating him so severely that he died three days later from the injuries. The emperor — the same one who two decades earlier had presided over the Nestorian controversy — accepted the decrees of the council and died promptly a year later. A new emperor called for a new council, and that was Chalcedon.

With some five hundred twenty bishops nominally in attendance, the Council of Chalcedon was the largest in size of all the Ecumenical Councils. The results were the overturning of Ephesus II, deemed a council of robbers, and the anathematization of Dioscorus and Eutyches, whom the emperor then exiled. A Greek translation of St. Leo’s Tome (the Pope again electing not to attend) was read and debated; accusations of Nestorianism were raised, and the Pope’s letter was judged against the standard of St. Cyril’s writings, in which instances it was deemed sufficiently orthodox, despite variations of linguistic expression. Attention was being given not just to what words were used but what meaning was intended. Special effort was made to conduct the council the opposite way that Dioscorus conducted his.

No new creed was adopted, but the Council of Constantinople with its expansion of the Nicene Creed according to Athanasian and Cappadocian theology was recognized as an ecumenical authority. St. Cyril’s Council of Ephesus was universally embraced as the Third Ecumenical Council and a standard of truth. There was a collective consciousness of the historical pattern now. Much deliberation went into the new Christological confession that was needed. This, then, is the Definition of the Faith bequeathed to the whole Church:

We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with one consent, teach people to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly man, of a rational soul and body; consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin; begotten before all ages of the Father according to the Godhead, and in these latter days, for us and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary, the Theotokos, according to the Manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only-begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably (ἐν δύο φύσεσιν ἀσυγχύτως, ἀτρέπτως, ἀδιαιρέτως, ἀχωρίστως); the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being preserved, and concurring in one Person (prosopon) and one Subsistence (hypostasis), not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, and only-begotten God, the Word, the Lord Jesus Christ; as the prophets from the beginning [have declared] concerning Him, and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself has taught us, and the Creed (σύμβολον) of the holy Fathers has handed down to us.

For doctrinally uniting the two physeis of God and man in the hypostasis of Christ, for using the word hypostasis in continuity with Cappadocian theology, thus uniting the language of Triadology and Christology as though weaving one seamless garment of both — these are the reasons I believe the Fourth Ecumenical Council fits the omicron-symbolism of the cosmic chiasmus. There’s a theme of reconciliation and of fruitfulness here. For the Chalcedonian formula has proved an exceedingly fruitful pattern for the Church to follow in describing the loving union of opposites. I say that in full awareness that a painful schism has precipitated from this council and exists today. But I honestly don’t think even the non-Chalcedonian churches would be around today if not for Chalcedon. The hesychastic tradition (which pre-dates Chalcedon, of course) finds its fertilest soil in the Chalcedonian tradition of the Orthodox Church, and if not for the hesychastic defense mounted again Western humanism in the fourteenth century (unthinkable without the Chalcedonian formula), I don’t think any of the Eastern churches would have survived into modernity. Only the Church of the Seven Councils has been able to stand up and mount any kind of intellectual defense against the toxic river of antichristian humanism cascading out of the West. I think the non-Chalcedonian and non-Ephesine churches — all of which took root in linguistic cultures other than the Greek one in which the theology was originally conducted, and indeed may have been inspired primarily by resistance to the arrogance of the Greeks (which, hey, I think everyone who knows the Greeks can empathize with) — have in the last millennium of Western apostasy survived under the umbrella of the Chalcedonian Church. You’d be arrogant, too — pray for the Greeks. It’d be a shame if their umbrella collapsed.

But I was saying about chiastic structure.... I actually like the pentad of the first five councils better as a ksiasmus. I like Chalcedon as a parallel of Nicaea I, as foundational to Christology (with the mia hypostasis of its Definition) as Nicaea was to Triadology (with the homoousios in its Symbol). And both councils left a huge mess of resistance in their wake, to be attended to by their succeeding councils (both of Constantinople), which then also serve as ksiastic pairs, the Second and Fifth. But especially in Constantinople I’s anathema of Apollinaris, I can definitely see a chiastic correspondence between the Second and Fourth Councils as well. The dialectical alternation is clear: (α.) Arius’s heretical duality inspires (β.) Apollinaris’s heretical unity, which in turn inspires (χ.) Nestorius’s heretical duality, which doubling back inspires (ο.) Eutyches’s heretical unity.... Next, to complete the circuit, the Emperor St. Justinian will have to push back against heretical duality again, but this time in attempt to win back the Miaphysites put off by Chalcedon, even as the Second Council sought to reconcile the Semi-Arians within reach of Orthodoxy (and so I return again to a ksiastic model).

Ω. The Fifth Ecumenical Council — Constantinople, 553 AD

The Council of Chalcedon did not prevail politically for many years, as great Christological uncertainty abided and emperors just tried to keep the peace. Despite their efforts, whenever toleration for the Miaphysites prevailed in the East, the West would be greatly offended, seeing how intolerant the Miaphysites were to the Tome of St. Leo. A thirty-five–year schism ensued between Rome and Constantinople. As I say, the fallout of Chalcedon was similar to that of Nicaea and required a council to resolve.

The Fifth Ecumenical Council in 553 was all Emperor Justinian’s doing, and everything about the long reign of Emperor St. Justinian, from 527 to 565, was strikingly apocalyptic. This is the omega-council. Did you know there was something called a Little Ice Age during this time? Volcanoes in Iceland were the material cause, unbeknownst to the Roman world — all they knew was that in 536 the sky went dark and the sun shone without brightness. Temperatures cooled and crops failed. The climate remained in a downturn for decades. Then in 541 a plague like nothing recorded before broke out first in Egypt and then throughout the Roman world. Researchers call this the first plague pandemic, that is, the first appearance of the bubonic plague that in the fourteenth century would take out half of Western Europe. The very first wave of it in the sixth century was known generously at the time as “the plague of Justinian.”

Justinian was a plague on the non-Roman world, for sure. Ascending to the throne with youth and energy, he took it upon himself to extend the Empire’s borders as much as possible, putting the kingdom back in order as it were, which importantly required reclaiming the West from Germanic barbarians. In 535 (just before the volcanic winter descended on Europe), Justinian began warring against the Ostrogoths in order to take back Italy, and battles went back and forth there for the next two decades. You can’t have a Roman Empire without Rome, so he thought, and Justinian was a native Latin speaker from the southern Balkans. Many successful campaigns were had, West and East, and the Roman Empire reached its apex in size under his reign.

But his earliest big test was a local insurrection in 532. Now I get to talk about the Nika Riots, which I’m very excited about. This will be relevant to the Fifth Ecumenical Council, I promise. The Constantinopolitans loved the Church, but they also loved chariot racing; the Hippodrome was a rival to Hagia Sophia for the hearts of the people. The sport of chariot racing was divided into teams known by color, originally four teams, but in the sixth century the Blues and the Greens were the only ones with any pull. So popular was the sport, that the identity of which team one supported threatened to disrupt more essential identities. Emperor Justinian was from a Team Blue background, but tried to stay impartial while enthroned. His wife the Empress Theodora was from a Team Green family originally, but they switched sides to Team Blue when she was yet a child because her widowed mother wasn’t being properly cared for by Team Green. This is the kind of Christian society we’re talking about here, where among a certain segment, the care of widows was left to sports fans instead of to the Church community — sports fandom was an exceedingly strong cultural signifier. Fans invested a great deal into their teams, and violence regularly broke out at racing events not unlike with football hooligans in our own era.

Now, there were economic problems in the city that people were upset about. On account of the wars Justinian waged, taxes were high, especially on the wealthiest citizens, who thus weren’t so incentivized to keep order. A football riot happened — excuse me, a chariot-racing riot happened, and there were murders. Authorities cracked down on those responsible and staged a public execution of several culprits from both Teams Blue and Green. Two of the executions were botched when scaffolding broke, and two men, one Blue and one Green, escaped to a church and sought clemency. Justinian refused, and rioting began. Rioting was not uncommon in this age; it functioned as a sort of democratic check on imperial power. But this time was different, perhaps (I suspect) because the wealthy upper class harnessed its power for its own greedy ends. Urban corruption on this scale doesn’t just come from the bottom up — a large portion of Constantinople was destroyed. Rival Blues and Greens teamed up in opposition to the Emperor like the polarized lower passions, desire and anger. Hagia Sophia, the central cathedral of the entire Roman Empire, the place where emperors received their power in the sacrament of coronation, and hence the symbol of all authority in the land, was burnt to the ground.

It was so bloody apocalyptic. Imagine NFL fans both Democrats and Republicans storming the U.S. Capitol (hard to imagine anyone doing this, I know) and actually burning it down. Then as the President hides in a bunker, imagine the rioters inaugurating their own president at the Super Bowl. That’s what happened. As Justinian hid in the imperial palace figuring out what to do, the Blues and Greens got together in the Hippodrome and crowned their own emperor — in a sports stadium! This, after burning down the cathedral of Christ where coronations are supposed to take place! The Nika Riots were as ungodly as rebellions get.

Well, St. Justinian matched their apocalypse with one of his own. His response provided the pattern of how to react in an eschatological situation when two dialectically opposed rivals synthesize their forces against an image of God Incarnate, such as a holy cathedral or a God-anointed ruler. (A similar situation occurs in the Gospel when Pilate and Herod, previously at enmity, make friends over the execution of Christ [Luke 23:12].) While the rioters were gathered in the Hippodrome to hear their false emperor speak, Justinian, being affiliated with Team Blue, sent an unarmed emissary with a bag of gold to give warning to the leader of the Blues, and a chance out. A reminder was given that the false emperor they had crowned was from Team Green, after all. (This move is reminiscent of when Paul identifies with the Pharisees in order to set his Pharisee and Sadducee accusers against each other [Acts 23:6–8].) Some of the Blues took the opportunity to leave the stadium, and they were saved. Justinian did what he could to minimize the bloodshed. Next his army descended on the stadium and decisively ended the rebellion. The emperor they had crowned was executed. Wealthy senators who had aided the revolt were exiled. As a result, in a stunning turnaround of just five years, Hagia Sophia was rebuilt from scratch with a brand new design, and it remains standing today, the greatest edifice the world has ever known.

Yeah, so, that’s the location where the Fifth Ecumenical Council took place, and in a way I just told its whole story. For, to secure the Western empire, Justinian went to war. And to secure the Eastern empire... he also went to war, with Persians — but he knew most of all he had to go to council with Christians. St. Justinian was a philosopher-king, extremely knowledgeable in theology, writing important works of his own. Historically he played a pivotal role in Christological understanding, ensuring an Orthodox, Cyrillian interpretation of Chalcedon and enshrining it as the Ecumenical Council that it is. But the story of Justinian’s Council, Constantinople II, is an incredibly daunting one to tell (especially with any kind of brevity) because it’s so complex, and because its pattern is so unique. My attempt at this narrative will be more symbolical than historical.2 Constantinople II was the council to end an era, an omega-council, recapitulating all that came before it. There was no innovative heretic at the time who needed silenced. There were no new heresies that needed to be combatted, just centuries’ worth of old ones to clean up in an effort to forge for the Empire, at the peak of its powers, an eternal unity that reflected the unity of Christ. “I believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church,” the Symbol of Faith said. And yet opinions on the identity of Christ were so divided, a crisis compounded by differences in both meaning and expression, but not always together and not always in that order.

So all the anathemas issued were against figures that had been dead for a century or more, primarily the two dialectical extremes of the Antiochene and Alexandrian schools, guilty of abuses in either direction: Theodore of Mopsuestia (d. 428), friend of St. John Chrysostom, teacher of Nestorius, and foundational hero to the non-Ephesine churches, on the one side; and on the other, Origen of Alexandria (d. 254), teacher of many saints, whose highly unorthodox speculative cosmology was kept alive by monastics for centuries, but the errors of whom were not directly related to non-Chalcedonian Miaphysite theology. For when it came to dealing with these dialectically opposed anti-Ephesine and anti-Chalcedonian factions, Justinian certainly had a favorite. The entire purpose of his ecumenical council was to prove to the Miaphysites (Team Blue in this instance) that the Council of Chalcedon accorded with Cyrillian orthodoxy — to which end, with great resolve, he threw the non-Ephesine supporters of Theodore of Mopsuestia (Team Green) under the chariot.

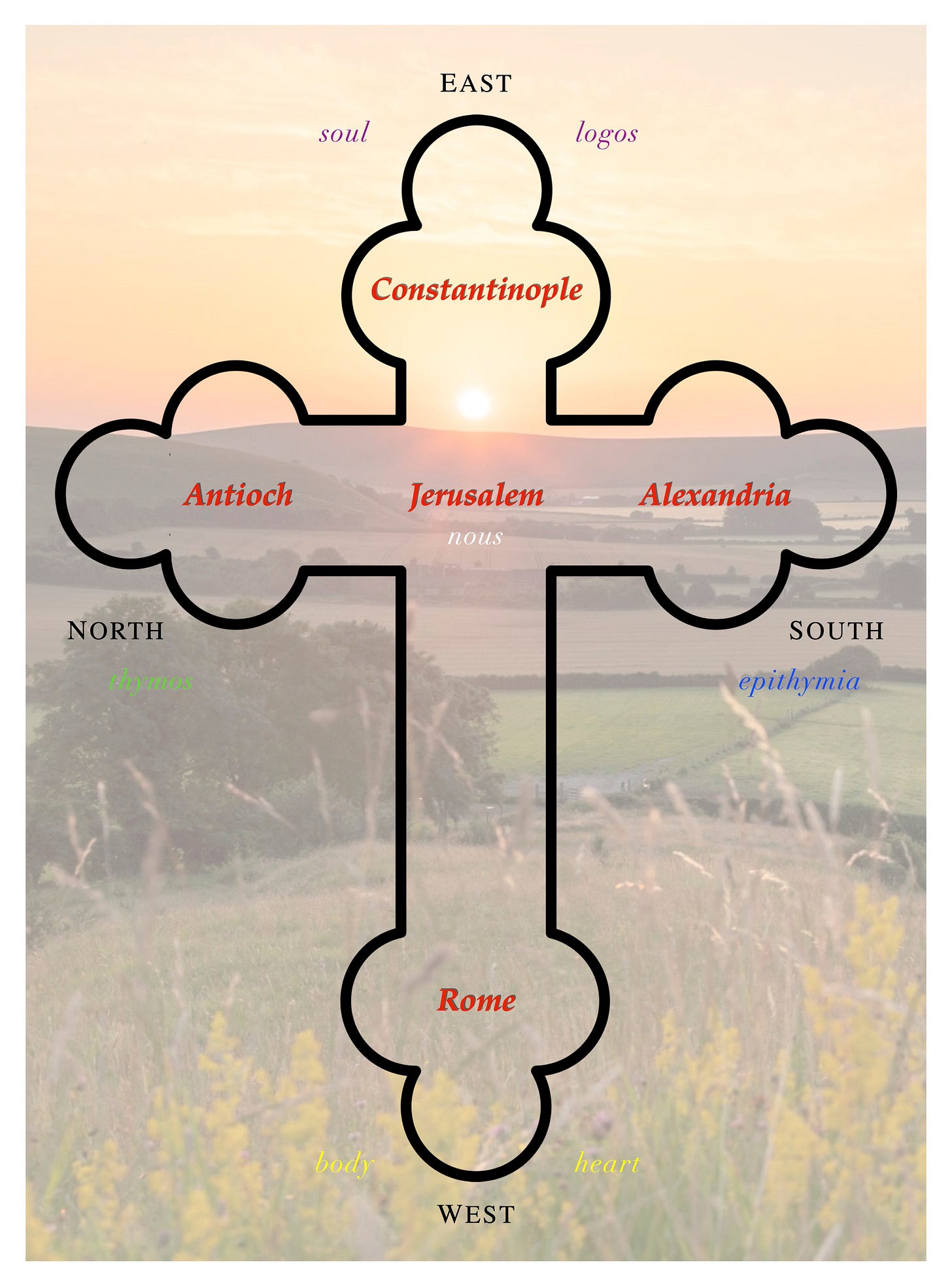

Now I wish to speak more about the symbolic meaning of this dialectic. Essential to consider, the imperial centers of Antioch and Alexandria were the heirs of two polarized cultures created in the bygone Macedonian Empire. The tension between them erupted in the wake of Alexander the Great’s death, when Seleucid Syria and Ptolemaic Egypt were divided into two competing kingdoms. When the Prophet Daniel tells of the King of the North and the King of the South, the immediate historical meaning is these two Hellenistic kingdoms. As the Bible tells it, God’s people in Judea were caught between these polar opposites like a soul torn between the passions of anger and desire, or thymos and epithymia, a polarized pattern I’ve written about often. Seleucid Syria was a heavily martial society, representative of thymos, who oppressed their Judean neighbors with physical violations, as Antiochus IV Epiphanes did in the time of the Maccabees. Ptolemaic Egypt was an agricultural powerhouse which had its military might, but identified most of all with its sensual and intellectual appetites, representative of epithymia, as demonstrated by the famous library at Alexandria, a cosmopolitan center for multiple cultures. This kingdom was more likely to violate Judeans with its love of worldly knowledge and embrace of all religions, seducing them with desire.

In a Christian setting — which was established once the faith of the Maccabees had overcome these two kingdoms by way of the Incarnation and Christian martyrdom — the lower passions of thymos and epithymia are to be converted to their proper use, and so also with the cultures of Antioch and Alexandria. Hence different exegetical schools, both amenable to Orthodoxy, both capable of heresy, organically developed in these two places, according to their respective characters, thymic and epithymetic. Whether you prefer a controlled meaning of the text through historical interpretation or an open-ended exploration of the text through anagogical application will depend on your personality, weighted towards either thymos or epithymia (as though by gender). As with magnets, though, the poles are contained within each other; the pattern is fractal. The best representatives of either school will feature a range of interpretation indicative of that fractality, even if a proclivity is discernible through faithful transmission of one’s local tradition.

As it happened, in the Antiochene school the same thymic preference it had for the historical meaning of a text turned, in Christology, into a preference for expressions of the two-ness in Christ, stressing what we now call natures, physeis. Divine and human properties have to be distinguished. Indeed, as Chalcedon says, there can be no confusion between the two; this is a thymic imperative. The Incarnation isn’t real if the divine Logos doesn’t retain consubstantiality with the Father while gaining consubstantiality with His human creatures. And deification, the purpose of Christ’s saving work, falls apart if ever that which deifies and that which is deified are confused for each other.

But in the Christian experience, attraction to what’s right is more foundational than repulsion to falsehood. Encounter with the Hypostasis of Christ, His Person, is more central to the foundation of being than the collections of natural properties. You can’t have one without the other, naturally, but there is an order to things. You have to start at the base. Eve disobeyed first, so Mary obeyed first. Not Joseph — men come second. News of the Resurrection had to come through the Myrrhbearing Women. If you tried to source it through the male apostles first, with all their masculine propensity for doubt, it wouldn’t have gone anywhere.

The feminine desire for the beauty of the Person of Christ is the best way to approach Him, is what I’m saying; that orientation scales up in the Christian life. The masculine repulsion to falsehood is also a valid entry point, but if that’s how you meet Christ, you have to reorient yourself in order to move forward (you have to fall in love). So this is the pattern: Antioch, because it’s thymic, like a good husband has to sacrifice himself and show preference for the life of his wife. Alexandria, because it’s epithymetic, like a good wife has to respect her husband and obey him. I’m talking about theology, I’m talking about history; I’m talking about the proper order of the Christian soul.

Alexandrians, in epithymetic attraction to Christ the Savior, emphasize the uniqueness of His self-subsistent reality (whether it’s called physis or hypostasis) as well as the unity into which He brings all things created and Uncreated. Without thymic discipline, though, this epithymetic emphasis can cost Christ His consubstantiality with God and men and turn monstrous. As a hermeneutical analogy, one’s speculative interpretation of a text can easily go off the rails if it’s not grounded by due respect for the historical context. But in terms of Christology, if in your worship you make Christ so unique that He becomes some kind of unicorn neither God nor man, then you can find yourself worshiping an idol of your own desire, neither godly nor human. Speak to Miaphysites today as a Chalcedonian Orthodox, and you will not commonly be inspired to make this straw man argument against them. The prospect of ecclesial union will appear close at hand. But all the same their churches’ histories impel them to rebel against even those Antiochene expressions of duality which are compatible with Cyrillian orthodoxy, like those incorporated into Chalcedon — or the Tome of St. Leo.

The Roman angle, however, brings up a whole different dimension of the controversy, and a different analogical aspect of the spiritual life to match. Much of the conflict surrounding Justinian’s council involved Pope Vigilius’s botched attempts at representing the West’s opposition both to the Miaphysites, on one hand, and likewise to the condemnation of Nestorian-adjacent Antiochene expressions of duality, on the other. This history is too serpentine and shadowy to recount, but suffice to say, the Roman church in the end accepted the council in her books but not in her heart. It doesn’t seem the Western church ever really understood the substance of the debate or the stakes that were at play. Even today it’s hard for a Westerner such as myself to approach the topic.

For while Antioch and Alexandria are joined on a north–south axis, Constantinople and Rome are joined on a east–west axis. It’s also a Greek–Latin axis, and any good Alexandrian exegete could tell you that Greek and Roman cultures relate to each other like soul and body. Whereas Greeks bring the philosophy, the science, the arts, the Parthenon, Romans bring the laws, the roads, the concrete, the Pantheon. Romans’ gift for infrastructure provides the body of the Greek soul, even as Virgil saw Rome as the reincarnation of Troy. When in Scripture you have the juxtaposition of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, as on the Cross of Christ, it can be interpreted variously as praxis, theoria, and mystagogy — or body, soul, and spirit. Put the Holy City of Jerusalem in the center of the two axes, with Constantinople in the East as the new Troy, and here is the anthropological map of the five patriarchates, the chiastic pentarchy first put into the law by none other than Justinian the Great:

Constantinople is the logos, chief faculty of the Greek soul, tasked with minding the thymic and epithymetic powers. Rome is the body, the center of which is the heart. When Paul insists on journeying from Jerusalem to Rome, he’s retracing the Incarnation, the embodiment of God; he’s telling a hesychastic story about the nous descending into the heart. Rome has primacy based on this fact: that it occupies the lowest cosmic position, to which the Gospel must always journey in order to testify to the fullness of the Resurrection. That does not mean the body gets to tell the soul what to do. The desires of the body shall have no currency in the Christian soul, none but its natural desire to be raised up and made spiritual. The body must accept discipline from the soul, but also the chastened body is the teacher of the soul. (I’ve written about this chiastic relationship elsewhere; it all applies here.)

The Latin Tome of St. Leo, for example, performed an excellent service to the Council of Chalcedon by helping to temper Miaphysite excess, but its orthodoxy is measured against the Greek Cyrillian teachings which can be described as beauty-first for their emphasis on unity. Rome favors Antiochene patterns because it is of the body and understands things of the body — the material realm, the historical text. But the corporeal Latin tendency then is to reify ideas, to concretize concepts like “nature”, which would seem to deflect agency away from hypostasis, which can also be reified in damaging ways. This remains a problem for English-speakers such as myself. The Cyrillian tradition has the advantage of not thinking that way, but its anagogical preference for paradoxical expressions and ambiguous definitions can be less helpful for guarding against error. The Fifth Ecumenical Council threads this needle beautifully, providing dogmatic Christological expressions that retain and protect the mystery of the one incarnate Hypostasis of God the Word. The Cyrillian understanding of Chalcedon thus achieved may not have won over the Miaphysites — making this council a failure by its own standards — but the writings of St. Maximus the Confessor and the whole philokalic tradition that follows him rest on its shoulders....

I have to stop here, but I also have to admit it’s hard telling this story and calling Justinian “St.” without at the same time discussing the aspects of his life which are definitely not reasons he’s a saint. I don’t have the space here to relay the history — even though the fact that the leading theological figure of this era was an anointed emperor, not an ordained hierarch, is very symbolically significant. I’ve said the state is like the body and the Church the soul, but let’s not let the two natures of man blind us to the unity of the person! When we talk of the unity of Christ, by extension we also mean the unity of His soul and body. Christ is both priest and king. Meaningfully, when an emperor received communion, back when the Church had political embodiment, he did so in the altar alongside the priests. When Hagia Sophia was completed, Justinian walked inside and marveled, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee.” Indeed, typologically, the comparison is apt. As a Church-anointed son of David, Justinian fulfills the role of a christ, but inevitably in some ways, also the role of an antichrist. It’s all so apocalyptic — and therefore, to us dullards, very cryptic. The Church remembers King Solomon fondly, and St. Justinian as well. The Acts of the Fifth Ecumenical Council were his books of wisdom.

Gah…

Would you believe, when I set out to write this article, that I thought I’d be able to hammer it out in a day? “All the ideas are already in my head; I’ll just sit down and write them out.” I had no idea.... No idea. My hope for this year was to write quick, inspiring, easily digestible articles, the kinds of things people want to read. Then I open up my mind and discover the real scale of what’s inside.

I have to finish this article. I intended to post it in honor of the Sunday of Orthodoxy, and here I am a week later, on the eve of the big day, not having reached the restoration of icons in time, the very reason for the feast. Why wouldn’t it have occurred to me that I can’t write a brief history of the ecumenical councils the size of a Substack post? Lord, please forgive me and have mercy on me, and grant me the guidance to know how best to use the quickly dwindling time I have left.

Part 2 is now available here.

For my patristic presentation here, see John McGuckin, “St. Cyril of Alexandria’s Miaphysite Christology and Chalcedonian Dyophysitism: The Quest for the Phronema Patrum,” The Dialogue Between the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches, ed. Christine Chaillot (Volos Academy Publications, 2016), pp. 33–55. It’s really a great read.

For further reading, I direct others to Richard Price’s volumes on The Acts of the Council of Constantinople of 553, with related texts on the Three Chapters Controversy (Liverpool University Press, 2009). And the theological works of St. Justinian are introduced and translated by Kenneth Paul Wesche in On the Person of Christ: The Christology of Emperor Justinian (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1991).

Thanks for this, I am woefully ignorant on practically all of the goings ons of the ecumenical councils. This has been a good primer/overview for me to understand in braid strokes what happened.

Great article Cormac. The chariot racing team rivalry history is too good to be true! At the very least you are helping me remember what happened at each ecumenical council :)

Have you ever looked at an octave structure in the weeks of the Triodion? It may make for an interesting Lenten article...