“The West Must Repent,” he blogged

“Die”, “repent”.... Same thing. This is the one where I gab about McGilchrist and Kingsnorth (and some Dreher for ballast)

I’d sure like a break from the rigor of writing a new essay this week, but I still want to write something new. Well, mostly I just want to amuse myself making images, but I’ll need some text to spread them apart. So I apologize ahead of time, but this’ll just be the bloggiest attitude I’ve ever assumed in this journal. I hope with the looseness of opinion-slinging there can be had a little renewal, even if it gets a bit messy....

Last week Symbolic World contributor (and published author and Salvo columnist) Robin Phillips sent me the following instigation:

I want to ask your thoughts on something. This week both Rod Dreher and Paul Kingsnorth (who, I understand, will be present in Dublin this weekend with Jonathan) suggested in their substack newsletters (see here and here) that it’s time to give up on the West. They both draw on the work of Dr. Iain McGilchrist. Backed up by what appears to be the irrefutable evidence of science (i.e., McGilchrist’s supposed discovery that the brain’s left hemisphere leads humans to create unsustainable civilizations that function as ticking doomsday machines) these thinkers are now embracing revolutionary language about uprooting the west.

Conservative thinkers, particularly those steeped in Edmund Burke, will find this a hard pill to swallow. Must we really give up on the civilizational order that gave us Shakespeare, Bach, and antibiotics? Is this the price we have to pay in order to achieve “Bush Christianity”?

For Paul, the West is not even a meaningful concept; for Rod, our fidelity to the West is just patriotic sentimentalism — something that started with nominalism and ended with transgenderism and is now so rotten to its core that there is nothing left to preserve. If one adopts such notions, then of course one cannot work within the current order, but must only agitate for its downfall. As Paul wrote, “the west must die ... I want to uproot it.”

Such ideas have real world consequences that we should be concerned about. As I pointed out in my response to Paul’s previous essay, once we conclude that the current order is unredeemable, and once we adopt the type of deterministic fatalism in McGilchrist’s theory of history’s cycles, we will become disincentivized to teach our children and students how to behave with virtue within this order (for example, teaching them how to be virtuous when using AI). Instead, virtue becomes entirely about withdrawal and hence the type of primitive Christianity that Martin Shaw is giving voice to.

This isn’t the first time Christians have embraced revolutionary ideas on the heels of fashionable science. Yet it isn’t clear that McGilchrist’s theory of the brain is even consistent with a design framework (see the concerns I raised in my Salvo column), and I have a huge hesitation with the growing trend to build a de facto theology of culture around his, so called, discoveries. If you watch the documentary The Divided Brain (which McGilchrist himself endorses), it’s clear that his work is being weaponized for a type of animism, a neo-primitivism in which there are no distinctions, no borders, no differentiations, and no ultimate difference between animate and inanimate life. Is this really the prophet we want to lead us into the promised land of the Bush Christianity?

I’d love to know your thoughts!

My opinions? By demand?! Woo hoo, let’s BLOG!!!

I can’t speak first-hand to the concerns of conservative thinkers not being among them myself. The polarized conservative-liberal dialectic gripping the Western mind is not something I can use to describe the way I think. Nor do I think I can help anyone teach children how to be virtuous when using AI, which sounds to me rather like teaching children how to be virtuous exploring sex. The comparison isn’t random: sex is how we as persons reproduce, and the project of AI is channeling our energy as a nature to reproduce. Thus our society-wide drive to force AI into consciousness resembles so many horny teenagers either wrecking their lives having children out of wedlock or else short-circuiting their ability to love others by addicting themselves to self-pleasure. Chastity — we need to learn the wonders of chastity regarding technology, even in the contexts of marriage where sex is permitted, if you catch my drift. All technology is an extension of something we already do. The technology that extends our reproductive capacity to the scale of our common nature, such that our nature could birth another nature in our image, needs to be treated with the same strictness as sex. Until our marriage to our Bridegroom is sealed, we shouldn’t be doing it. Admittedly, I wouldn’t expect Robin and me to be without common ground on this point (I certainly don’t argue against information literacy, for example).

But nonetheless, I think I’ll be writing about AI next week, so I’m much more interested in addressing the meaning and influence of Iain McGilchrist’s work, insofar as I have opinions on the matter. ’Cause I do! So let’s go! C’mon, these images aren’t going to space out themselves!

Reducing culture to brain science is symptomatic of the very sickness McGilchrist is attempting to diagnose. That should be clear enough, to begin. No one should have that takeaway from what McGilchrist has to contribute since he delves so deeply into the liberal arts, granting them so much importance in the effort to overcome the reductionist worldview. It’s debatable whether anyone does have that takeaway, though I see the point in Robin’s concern, especially regarding McGilchrist himself, since the general thrust of his philosophy is such a self-defeating flop.

McGilchrist (I’ve only read The Master and His Emissary — well, and The Matter with Things’s introduction, free for preview on Amazon, which functions as a great summary and is where I recommend others begin) is so left-brained in his attempts to cure left-brain dominance as to be sheerly tragic. It can play a role in helping, for sure, like John Nash using logic to realize logic has made him a delusional schizophrenic. But it’s not going to heal the cultural schizophrenia. I know what would, but nowhere does McGilchrist participate in that which he condemns more than when giving his takes on the Christian faith, which reveal copious Western bias and ignorance. It’s a shame. His ideas about synthesizing the left and right hemispheres amount to an airball, a perfectly calibrated twenty-foot jump shot (a thing of beauty, really) thirty feet from the hoop.

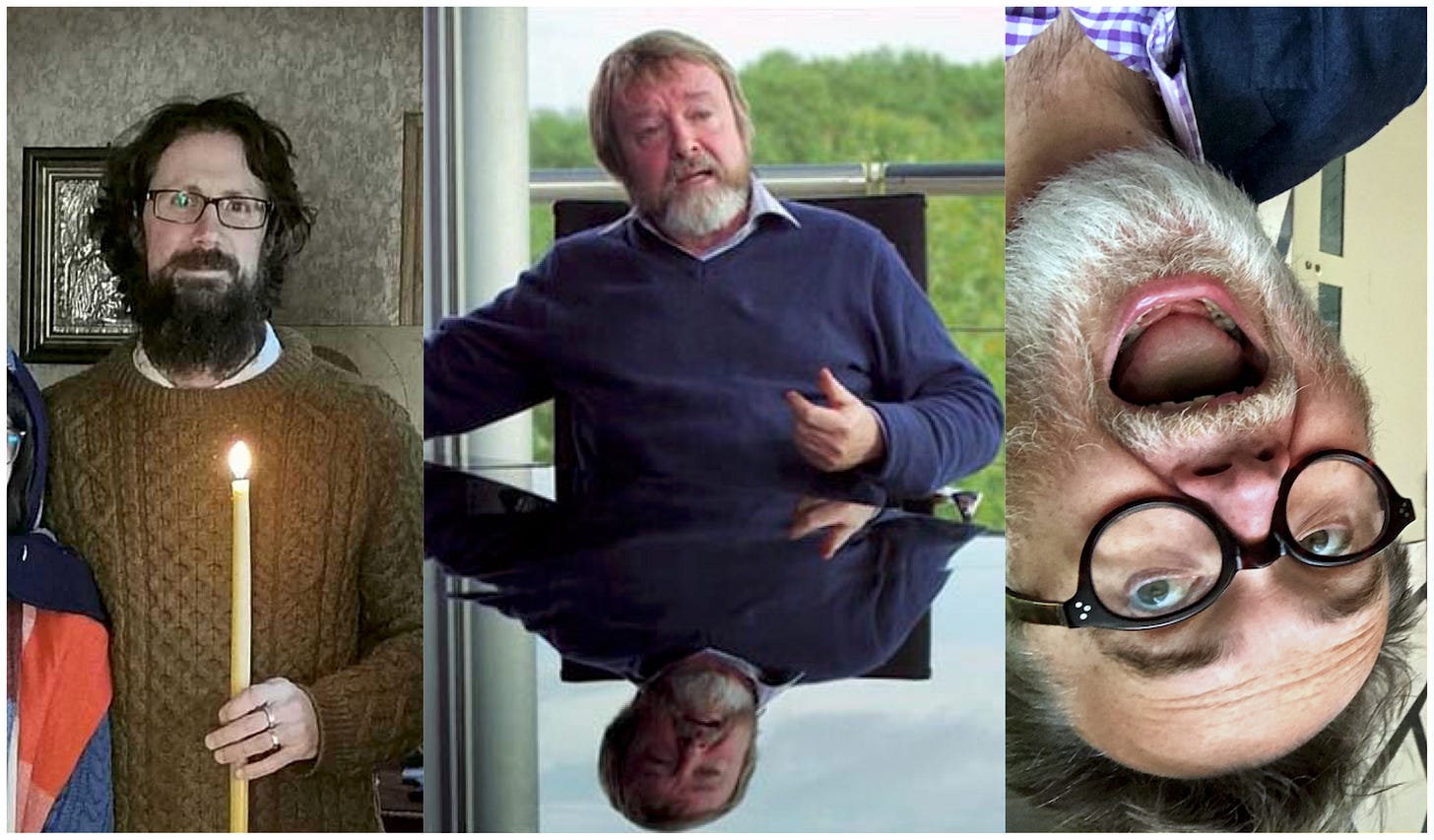

Kingsnorth, for his part, is a man — a man who writes novels (two that I’ve read) about men who are locked within their manic first-person thought processes and can’t get out. He is prone to extremes and is going through a conversion process. Zealotry may get the better of him sometimes, but I wouldn’t worry about anything he says in a blog post as if his growth is done and his ideas have stopped. I’ll have more to say about him in a paragraph, but first....

Dreher in his newsletter response explicitly resists Kingsnorth’s call to abandon Western culture; indeed his psychological well-being is grounded in it, so that makes sense. Where would Dreher be without the Gothic France of the Chartres Cathedral, or the Italy of Dante’s Divine Comedy and Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia? He would be the noxious puddle of refuse so many accuse him of being, and he knows it. But he’s still got a polarized political mindset that really exemplifies that writing and thinking are two different talents. He writes compulsively but doesn’t think to the same level of proficiency. His role seemingly is to garner the attention of many using politicized indignation, but then to pass people’s attention along to moderately more holistic thinkers, which greatly to his credit he does have a nose for, transcending all political limitations. As for his books, I haven’t read them, but the impulse to go to Eastern Europeans who suffered under totalitarianism to learn survival skills is absolutely the correct one. Reading his blog on a regular basis, however, seems to me a really unhealthy thing to do.

Speaking of unhealthy, Kingsnorth for too long has been circling his mind around “The Machine”. It’s too overwhelmingly negative a pastime. If he can’t look at a monk with a smartphone and not have judgmental thoughts, he needs to adjust his perspective. Be the bee that attends to the flowers, not the fly that circles the dungheap. That’s Orthodox spirituality 101 (may St. Paisius of the Holy Mountain be the teacher of us all!). Again though, his behavior is not altogether inappropriate for a convert — you have to go through a stage of negative separation; the Ladder of Divine Ascent begins with renunciation and exile — and it doesn’t worry me. If he has found a good deal of popularity and influence for a reason other than his evident literary skill, then I can only imagine it’s because he’s meeting people where they’re at, which someone’s got to do, and I trust him for the job. Lord knows I don’t have the talent to do it! Later stages of conversion, regularly, are much more graceful and discerning. I don’t say that to knock Kingsnorth, but to pay proper honor to the Holy Spirit, years of sacramental union with Whom is not not going to be utterly transformative for him. I’d expect him to be looking forward to this, even as he keeps his head down and traverses his present terrain.

[Insert segue into Dreher-style confessional.]

I’ve been an Orthodox Christian for twenty-three years, beginning my conversion my first year of college in my late teens. I was raised Roman Catholic by a mother motivated by a guilty sense of obligation that abruptly stopped once (1) I went through Confirmation, fulfilling all my mother’s obligations, and (2) my parents’ marriage died by way of a vicious schism (long in the works), two things that happened within a couple months of each other when I was fourteen. I don’t identify with my Catholic upbringing (which I promptly abandoned as soon as I could), but rather with the secular humanist culture in which I was immersed from childhood and on which I focused, to devastating effect, in my pivotal middle teen years. I’m a Westerner and an Irish American — a national identity my sense of which was only intensified and enriched by my conversion to Orthodoxy. My sisters and I grew up with a strong sense of Irish identity, sourced from a wide community of family and friends, and reinforced by what we saw in the media; the annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Pittsburgh was a big deal. Yet I never felt so Irish as when I became Orthodox. Only then did I have access to the way of living that the ancient saints experienced (which I’ve written about here and here) — oh, culturally there remains a millennium-sized divide, but in the spiritual unity there is a secret passageway between the ages. I love the pre-Schism Western saints and follow in a tradition of other Orthodox converts who do the same (my favorite writing by Fr. Seraphim Rose being his lengthy introduction to St. Gregory of Tours’s Vita Patrum).

Meanwhile I am all torn up and deeply disturbed by the long-in-the-works divisions and apostasy coming to a head in the Orthodox churches the past few years. I’m increasingly convinced Rome originally, by means of a masculine sacrifice, played an important binding role in the communion of churches that we are suffering from the lack of. Various yokes through the last millennium (primarily the Turkish yoke and the Communist yoke) prevented us Orthodox from feeling the effect of Rome’s apostasy, but now the sutures have been removed and our wounds are gaping.

Regardless, no amount of wishing for Rome’s return to performing its sacrificial role for the Orthodox Church will make it happen. I have no illusions about the history of apostasy in the post-Schism West not being the very source of everything negative plaguing the modern world. Let’s do a bit of commenting on Kingsnorth’s words:

[T]he whole of this ‘West’, since at least the eighteenth century, has been a state of permanent revolution.

Eighteenth century? Shakespeare had this pattern of permanent revolution pegged already in the middle of the millennium. It’s all just Hamlet over and over again. “Oh no! Someone killed my father and took his place! Now I have to rebel and make it right! But I lack a father to guide me in doing so! So... I’ll just give it my all, and — Oh no! I’ve made everything worse and now we’re all dead!” Every generation a new Hamlet, every generation a new bloodbath. Replace the word father in that panic attack with “God”, or with “Church”, or with “culture” — it’s all the same sick pattern, one that was going on for some time before Shakespeare managed to articulate it....

Was this forged by that left hemisphere way of seeing, or was it the other way round? Who knows, but from France to Russia, Germany to America, Marx to Rand, 1789 to 1969, the aim has been the same: bring it all down. Break it all up.

The source of the sickness is spiritual, ecclesiastical even, not anything detectable by scientific means. Schism = schizophrenia. Bring it all down? Break it all up? This is the pattern of the Protestant Reformation, and the Catholic Counter-Reformation in reaction. It’s the churn of dialectic infesting the West since a couple centuries before that....

Pull it apart, examine the parts, put them back together in a better, more equal, more profitable, more human order.

You’ve got Scholasticism pegged, Paul.

But notice that the impulse to “bring it all down, break it all up” is being identified as what not to do. When Kingsnorth calls to let the West die, do we give him the credit of not making the same mistake he is castigating? He says he is speaking very abstractly (“I know this can sound very abstract”). But indeed, before that he speaks more aggressively; I refer to the line Robin quotes to me: “I want to uproot it.” That anger, it is true, needs to be tempered with discernment so as not to be self-defeating. In one’s rejection of evil, it’s imperative not to include anything good, just as in the embrace of good, it’s imperative not to include anything evil. Everything that is good about the West — which Dreher seems more inclined to name than Kingsnorth, though I highly doubt Kingsnorth fails to appreciate, say, Shakespeare’s genius at tracing the patterns of corruption — is something that we Westerners are charged with rescuing. We should very much fear failing in this our mission, whether it be on the side of rejecting something good or embracing something evil. The evil must be separated from the good; the good must be rescued from the evil.

To this end, anger against the dialectical churn of perpetual rebellion is maybe helpful at first in order to separate ourselves from it, but it has to be let go of to avoid being whipped right back into the churn. You can’t rebel against rebellion. You can’t dialectically oppose dialectical opposition. Not if you intend to escape its gravity and cease contributing to it! In defiant response to a culture of “bring it all down, break it all up” you can’t say, “bring it all down, break it all up” — obviously. And I hardly think this point is lost on Kingsnorth. This negative interpretation of Kingsnorth’s words is what Robin Phillips highlights, and I agree that’s a danger. But I think the dominant trajectory of Kingsnorth is towards the more abstract “letting” the West die. What we’re ultimately rooting for is the destruction of all that is destructive, the return of non-being to non-being. We’re reaching for the death of death, Christ’s glorious Resurrection. That’s the melody Kingsnorth is being pulled towards, the way the Lord goes down into the tombs and raises up with Himself everything good throughout all creation, separating it from the stink of death and divinizing it. That’s what should be happening to Western culture if it’s to be participating in Christ’s baptism. If ‘the West’ — a way of seeing, as Kingsnorth identifies it (not a meaningless conception) — is good at looking at things critically and rebelliously, then those God-given talents should not be rebelled against but put to their intended use, which is to rebel against sin and death and divorce and schism, to use the powers of critique as a source of renewal for the body of the Logos on earth. Such a service must be performed from the margins like a hero, however, or like a fool; it can’t become the central human function. Mere opposition to evil does not amount to achieving the good. Rebellion has to sacrifice itself like a man and move to the margins, if it’s to be of any good to others. In order to rise again, you first must recede beyond the boundaries of life. The West must die. This can be a very positive thing! In a Christian context where all things rise again, it can be just another way of saying the West must repent.

McGilchrist calls for the West to repent, it is true. And he falls short of repentance, so there is definitely a wrong way to do this. I don’t wish to discount that danger. I also can’t bear to see all the immensely valuable insights in McGilchrist’s research suffer disposal as if they’re worthless. Referring to McGilchrist’s work as a “supposed discovery,” or “so-called discoveries,” as Robin does in his question to me, does a gross disservice to what this man has accomplished. The Salvo article Robin Phillips links to only engages with a Canadian documentary based on McGilchrist (made with his participation) but not with anything he has written. The doc, which I’ve seen, is quite peripheral to McGilchrist’s accomplishment, being written and directed by people other than him, and in Phillips’s skeptical response to it I do not see a faithful representation of how McGilchrist himself writes about his ideas, which is much more nuanced and comprehensive.

So I’m impelled by love to see a rescue effort staged for McGilchrist’s ideas, though it’s hard to imagine that I myself would be worthy of doing it. I couldn’t do it in this short essay at any rate, and who knows where love will impel me next week and beyond. Let me at least put down some preliminary words. Consider this my contribution to the rescue team.

The patterns McGilchrist has discovered are real. But just because you have successfully perceived patterns does not mean you are interpreting them correctly. That is a fundamental maxim for symbolic thinkers to consider, one that I have had many occasions to recall, but I don’t think I’ve yet written it down. So let me repeat it: Just because you have successfully perceived a pattern does not mean you are interpreting it correctly. There is a temptation that occurs when you’ve hypothesized a pattern, checked it and had it confirmed — a temptation to mistake confirmation of the pattern’s existence with confirmation of the interpretative lens through which you’ve discovered it. After all, how else could you have discovered it if you weren’t thinking about it correctly, contextualizing it correctly? Very easily, actually! Heretics and the heterodox discover patterns all the time. And getting there first — being an innovator? — when it comes to discerning patterns, if anything that’s a warning sign that you are not interpreting things correctly, as I think the record of history shows. There is an article here I’ve yet to write on Origen and Evagrius and the dubious value of innovative thinking. Those who get to knowledge first often are biting into knowledge prematurely — that’s the pattern from the beginning of the global story. When you bite into knowledge prematurely, you’re not perceiving it in its proper context. This lack of perception goes far beyond just how you’re thinking discursively, but how you’re living, how you’re religious life is oriented, and how your soul is arranged. The scientific worldview, as I think McGilchrist will tell you himself, is a reductionist perspective that is bound to get things wrong even as it produces prodigious knowledge. This criticism applies to McGilchrist’s work itself in ways he does not see.

I’ve made enough abstract criticisms; it’s time to say something more concrete. Iain McGilchrist thinks the polarized pattern of thinking he perceives by means of copious neuroscientific research corresponds to what in ancient Greek thought was called logos and nous. Logos, the soul’s rational faculty, thus pertains to the more masculine left hemisphere of the brain, and nous, the eye of the soul, pertains to the more feminine right hemisphere. I can see why he would make that connection; it is not a nonsensical thing to say. The pattern sort of fits, but he is confusing fractal layers of psychology, and catastrophically so. I strongly believe the polarized brain pattern McGilchrist describes corresponds to the pattern rather of the two lower passions of the soul, thymos and epithymia. Logos corresponds to the totality of their cooperation. Nous refers to something not apprehensible by the scientific method.

I’ve written about thymos and epithymia many times (once again, the main articles: 1, 2, 3, 4.) But I’ve mostly covered the topic on the level of volition, on the level of praxis. There’s another level on which to understand them, the level of contemplation. For when Plato introduces his charioteer analogy in the Phaedrus, in which the highest faculty of the soul is depicted as a charioteer and the two lower faculties are the horses being driven, the legs of the horses and the wheels of the chariot are not the only means of locomotion. There’s an intriguing detail not to be overlooked, which is that the charioteer and both of the horses are all described as winged. These wings comprise a heavenly locomotion for the three powers of the soul, complementing the practical functions by which they move on an earthly plane. Again, not just the charioteer, but both the horses, thymos and epithymia — the repulsive and attractive powers of the soul — are winged. That which on the volitional level can be thought of as anger and desire, on the contemplative level can be thought of as... I’ve thought in the past (inspired by John Wild’s Plato’s Theory of Man) to call them conviction and conjecture. McGilchrist inspires me to refine how I describe these repulsive and attractive contemplative powers. Conviction (thymos) repels from vision what it rejects, isolating what it does not reject. Conjecture (epithymia) opens its gaze to all environs to pull in knowledge not possessed or mastered. Logos is observed in the negotiated cooperation of the two.

All creatures, as St. Maximus explains, are fundamentally passible in that they all have their origin in being passively moved from non-being to being. Thus this polarity exists at the core of our nature: we, along with all creation, are repulsed by non-being and attracted to being. In our fallen mode of existence, we first learn this pattern in the material, sensory terms of pleasure and pain, being attracted to one and repelled by the other. But that polarity is but a shadow of the polarity we may contemplate in our minds between being and non-being — between truth and falsehood. Longtime readers of my seven-month-old newsletter will see here coming together different threads of my thought into one cozy jumper. The whole of our embodied soul, or ensouled body, participates in this cosmic polarity witnessed to by our faculties of thymos and epithymia. The manner by which rational beings — who are endowed with the freedom to divert themselves away from behavior in accordance with their being and towards ways of non-being — direct their polarized powers and negotiate their fractal layers will determine the health of their souls and bodies, both personally and communally.

McGilchrist, though, by mistaking the pattern of the lower passions for the relationship of logos and nous, falsely believes he has climbed the mountain of human noology when he remains merely among the foothills. Arriving at knowledge through Western science, through dialectical emergence, he is bound to offer the wrong solutions to conflicts and a distorted image of the human being. He thinks by means of science he has held a mirror up to the nous and measured it? The logos, which I understand as incorporating all activity observed in the brain, I’ll grant you is something we can hold a mirror up to and see (which is not to say it can’t be misinterpreted when observed). It’s like the two-way speed of light. We can measure that (to varying degrees of success). I think the nous, however — as it has been known not by the ancient Hellenes, but by those initiated into the mystery of Christ, the holy Fathers and Mothers of the Orthodox Church — is something not visible by human means. The only mirror in which you could see it would be God Himself. Like the one-way speed of light, we fundamentally lack the objective perspective by which to measure it. Your perspective has to be outside creation in order to do so. You have to be deified in Christ, made wholly Other by grace. In presuming to have observed the nous in the epithymetic activity of the right hemisphere of the brain, McGilchrist presumes nothing less than to have achieved theosis by the power of his own intelligence. In fact all he’s done is lionize human desire on a contemplative level. From this catastrophically false deification precipitates the false religion Robin rightly picks on, the way McGilchrist proposes to synthesize culturally the two hemispheres. It’s as if according to his scientific method he has used a prism to divide the colors of white light and then, to get the white light again, mixed the colors together in a drab sludge on a painter’s palette.

No, to get the white light again, you have to humble yourself and put the prism down. Without even being generous, I think this is the gesture Kingsnorth and Dreher are recommending, the beauty of color spectra notwithstanding. The philokalic tradition of the Orthodox Church, in contrast to Western science, brings forth wisdom that emanates from above in purity, even as it emerges colorfully in the lives and writings of the saints who follow the Gospel commandments. It comes from the fruit of obedience, not the fruit of disobedience. It schools us in the way the world is supposed to be seen, as God sees it. It’s not a replacement of science as we’ve come to limit that word’s application, but it is the only context in which that science can be properly understood.

So I think in McGilchrist we may have a new Marx-like figure. The Marxist tradition offers excellent insights into the negative pathways of capitalism and how they work the destruction that they do. Yeah, but Gospodi pomilui, the solutions it offers are just bloody, rapid-fire ... airballs and turnovers. One does well to cite the Frankfurt school, for example, in understanding how the world works today, but doing so does not make one captive to Marxist conclusions necessarily. I think it’s safe to conclude, anyhow, that this is the spirit in which these Orthodox writers are citing McGilchrist.

The value of Martin Shaw’s “Bush Christianity,” on the other hand — which no one can hear or read without thinking, “George W. or George H.W.?” — is a whole different topic. For another day. Simply put, it’s real, it’s beautiful, it’s monastic. Its culture is both the fringe and the crown of secular life, not the replacement for it. Traditional Orthodox Christians understand this intuitively because they’re not captive to the dialectical, either/or mindset that developed in the post-Schism West.

This was another stressful week of writing, the fun I had with images notwithstanding (using algorithmic software, yes, but not artificial intelligence). I was trying to avoid stress. It didn’t work. Opinion-slinging is hard! All I wanted to do in the spaces between the pictures was forge a single analogy explaining everything to do with AI, comment on the schisms of the Church past and present, reprogram Western culture for Christian repentance, fix the entire corpus of Iain McGilchrist, explain by way of modern physics the difference between logos and nous in the hesychastic tradition, and not have to skip meals or feel pressed for time. Why was this so hard? Do I have an ambition problem? With all sincerity: Gospodi pomilui. May the Lord judge me now for my sins, that I not be judged later.

As a true son of the West, I prostrate myself to the ground and pray with all my heart, O Heavenly King, the Comforter, the Spirit of truth, Who art everywhere present and fillest all things, Treasury of blessings and Giver of life, come and abide in us, and cleanse of all impurity, and save our souls, O Good One.

this is exquisite; thank you

I also have duly recorded Cormac's maxim: "Just because you have successfully perceived a pattern does not mean you are interpreting it correctly."

I have been pondering an article on the hemisphere issue for a while, and you’ve given me motivation to think about it a bit more. I have enormous respect for McGilchrist, and have found his analysis of brain functions illuminating (and personally quite helpful), although I’ve puzzled over his overarching conclusion about the relationship of the two hemispheres.

From a Christian perspective—and from a fully human perspective—I think the core issue is not whether the left hemisphere dominates the right, or vice versa, but whether sacrificial love guides both hemispheres.

And I don’t think that love is reducible to either hemisphere.