What men really fear most about women — and why

On epithymetic violence and the unwitting profundity of a certain Margaret Atwood aphorism

A modern woman sees this famous photograph above, taken by Ruth Orkin in Italy in 1951, and her heart burns with knowing empathy. She has felt this overwhelming intimidation before, crowding all around her — at times in her life, it’s all she ever feels. She comes to expect it in public places. It’s most intolerable when it takes over her home life as well. Thus, how cathartic it is to see this internal captivity expressed in image by a female artist so plainly and powerfully, so that all the world may know what women suffer from the society of men.

I see that; I mark it well. I think it comprises an essential aspect of human experience in this fallen world. I also see an entirely different, less celebrated angle on this image’s genius. In the plurality of men and the singularity of woman, we have here a fractal image of our basic sexual situation. Many, many sperm, and just one egg. A staggering majority of sperm are created to strive purposelessly, to die having achieved nothing. Do you see the insecurity in these men’s comportment? Old and young alike, I see within them, as plainly as the fear on the woman’s face, the instinctual awareness of that quality that stalks our masculine identity all our lives and in the end seems to define it. I speak, of course, of our disposability.

Women are born with all the eggs they will ever produce already in their ovaries. As soon as they hit puberty, their months are numbered. This biological clock effects its own sense of doom. But in scarcity there is value. The relative rarity of female fertility makes women precious, worth protecting. Men, on the other hand, don’t begin producing sperm until puberty, but once they do, there’s seemingly an infinite supply. More so, men push through the age at when their female peers face menopause and continue producing sperm long after. True, sperm count can fall precipitously in old age, but such men are still well within the range of what can be considered fertile, so overabundantly fertile were they to begin with. In the egregiously overflowing abundance of superfluous glut, there is a vast world of meaninglessness, fractally layered with lack of telos, lack of purpose — strife to no end. The life of a man in this fallen world of birth and death is one of ineluctable disposability.

But lives of women are more valuable. “Women and children first!” is the slogan whenever disaster strikes and salvation is triaged. In the modern world if we were facing an extinction-level event and had to build an ark to save the human race, it would be irresponsible to reserve any room on it for men. What we’d want in the ark, rather, is as many fertile, genetically diverse young women as possible. The men would be replaced with a sperm bank. It would be judged a better allocation of resources. Men would be needed to build and defend the ark, but not to board it.

Fundamental to masculine identity relative to women, therefore, is our purpose in sacrificing ourselves for their lives. The preciousness of human life that we fight for is comprised of lives not our own. In times of war this can mean giving ourselves to be chewed up by the engines of combat. And in times of peace it can mean giving ourselves to be chewed up by the engines of industry. A man who righteously comes to terms with his masculine identity learns not to value his own life so much as his ability to provide for others. This at last brings me to the topic at hand.

It’s a very powerful saying that has been repeated many times: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.” Inconveniently, feminist author Margaret Atwood didn’t say this aphorism verbatim, although she should have. It’s a faithful condensation of what she did say in the course of a lecture at the University of Waterloo in Ontario in 1982:

“Why do men feel threatened by women?” I asked a male friend of mine..., “men are bigger, most of the time, they can run faster, strangle better, and they have on the average a lot more money and power.” “They’re afraid women will laugh at them,” he said. “Undercut their world view.” Then I asked some women students in a quickie poetry seminar I was giving, “Why do women feel threatened by men?” “They’re afraid of being killed,” they said.1

So she comes upon the observation anecdotally, accepting the words of a singular man into the ovum of her mind and being satisfied with that, not interrogating his response beyond the surface of what he said. Allow me, however, to speak for all the men who strove in this life so that just one of them could inspire Ms. Atwood’s estimable thought with an idea concerning them. For the observation that men are afraid that women will laugh at them, although seeming evidence of masculine privilege and tyranny, hides underneath it profound truth about the human condition.

Women root their value in their lives. They have been given the ability of life in a profound way, so their deepest fear will be that they will be prevented from realizing this ability. Typologically speaking, they manifest the character of epithymia, the passion of appetite. The appetite for life yearns for life more abundantly, and what threatens it most is death. Epithymia of course is common to all regardless of sex, and so we all have this appetite and this fear to some degree. The complementary aggression of thymos typified by men, meanwhile, since it is uniquely designed to serve those epithymetic needs by means of protection and provision, also uniquely presents the threat of transgressing those needs. But this power dynamic goes in both directions.

Men, whether virtuous or not, have their value rooted in their ability to provide for others. The deepest fear to strike them, therefore, will be that they will be prevented from realizing this ability. Typologically speaking, they manifest the character of thymos, the drive of... there’s no good, single word for it. In vice, the thymic drive is either angry and controlling or cowardly and irresponsible; in virtue, it provides and protects. (I’ve written of this many times in this journal.)2 Thymos too is common to all regardless of sex, and so women stand to learn much about themselves by taking seriously the patterns of behavior particular to men — and how, just as epithymia is threatened by thymic violence, thymos is threatened by epithymetic violence. This topic is so big, though, it deserves its own spontaneous heading.

Epithymetic violence

If a man is angry at a woman and wants to strike at the core of her identity, he will threaten her life. If a woman is angry at a man, she too will strike at the core of his identity. She won’t threaten his life, though, instinctively aware that he is already disposed (by nature if not by deed) to sacrificing his life for a greater source of meaning. No, she will threaten instead his ability to sacrifice for the provision of others. She attacks not his life but his livelihood. A man needs social acceptance in order to have a livelihood. Thus she seeks to ostracize him; she ridicules him — she laughs at him. She expresses pleasure at the prospect of his marginalization and through the attractive power of epithymia encourages others to feel the same. Already prone to disposability (whether he recognizes it or not), he thus is attacked at his primary source of meaning by the extremely powerful force that is the dragging undercurrent of desire.

Schoolchildren often get violent, it can be observed. When the violence is thymic, which is how boys typically do it, it is easily spotted for discipline. Mean boys get physical and lash out at other kids. When the violence is epithymetic, however, which is how girls typically do it (of course there is overlap in both directions on account of the fractal polarity), we’re less likely to catch it and correct it. Mean girls use the power of epithymia to suck attention away from the social needs of their enemies. They won’t attack your body, physically, but they’ll attack your relationships, socially. If a nice girl desires attention, say, and so plans to wear a nice dress to a dance, a mean girl might intentionally wear the same dress and make a bigger impression, diverting attention away from the nice girl and ostracizing her from the dance — without even going so far as making a surface-level decree; it’s all handled in the undercurrent of desire. By epithymetic violence I refer to this weaponized use of desire manipulating the attention of others to the harm of one’s enemies. The destruction wrought by this violence can be as great or greater as anything done by thymic violence.

These polarized patterns of violence I’m describing were known to the ancients and are embedded in their texts. The Prophet Jeremiah, for example, refers to it as “sword and famine,” a constant refrain in his preaching. Occasionally it’s a trio: “pestilence, sword, and famine.” The Hebrew for “pestilence” is rendered in the ancient Greek merely as “death”. I see in this a reference to the three powers of the soul. Pestilence/death is the capital plague proper to logos, the rational power of the soul. Sword and famine cover the lower passions. Sword refers to thymic violence, the result of being attacked thymically, while famine, the deprivation of necessary sustenance, refers to epithymetic violence, the result of being attacked epithymetically. (That nice girl exiled from the dance, crying her heart out in an empty classroom, is experiencing a type of “famine”.) Jeremiah warns his fellow Judeans these plagues will be upon them if they disobey the Lord. Toward the end of his prophetic career, he particularly says they will be preserved from them if they submit to the penance of Babylonian captivity, but they will succumb to them if, out of fear of them, they flee to Egypt instead (which is what they end up doing). This symbolic interpretation of pestilence, sword, and famine, preserves the relevance of the prophecy for all ages. At all times those who flee the consequences of their actions and in disregard of godliness manage lives of sensual pleasure instead, will be slain by the passions of ignorance, anger, and desire. And the famine afflicted by means of epithymetic violence is presented as equal partner to the thymic sword.

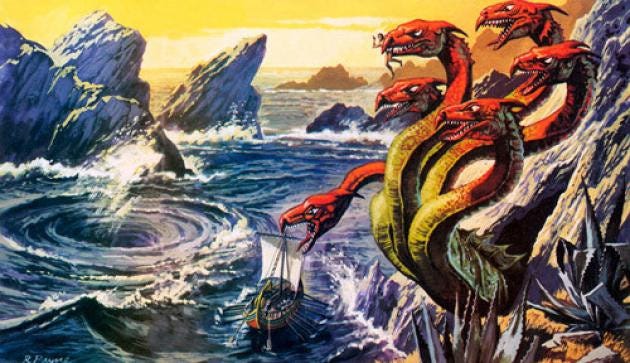

From the Homeric perspective, however, epithymetic violence is considered the more dire threat. The hero Odysseus on his maritime voyage home must pass through a strait with two mortally dangerous beasts on either side; to avoid one is to be at risk of the other. These beasts, Scylla and Charybdis, comprise a brilliant mythological image for the violence of thymos and epithymia. Scylla represents thymos with her six outward projecting heads on long necks that lash out at passersby. Charybdis represents epithymia as a whirlpool of suck inviting complete disaster for entire ships. Smartly, these two poles of the passions are depicted as contained within each other since Scylla, though she lashes out at you, yet consumes and swallows you, while Charybdis, though she sucks you in from a distance, yet after she has drowned you whole in her waters then spits you back out again. Circe (herself a predatory female) warns Odysseus to err on the side of the thymic attack. If you sail fast past Scylla, you risk at most six crew members, and the damage is limited. But if you sail too close to Charybdis, you could be pulled along more gradually into an abyss from which no one on your ship can escape because the ground has been sucked out from under them.3

Relatedly, one can well ask which 20th-century nation was better off after having suffered through totalitarianism, the Germans who endured it from the right, or the Russians who endured it from the left? The thymic violence of fascism creates a bright burst of traumatizing fire but has limited stamina. The Third Reich lasted but thirteen years, being at war for just seven, albeit long enough to commit whole-burnt offerings of genocide. The epithymetic violence of communism, on the other hand, lasted seventy years in Russia, the time needed for complete generational turnover of all peoples within their borders. Out of trauma Germany remained divided for the duration of the Soviet influence it called down upon itself, so I hesitate to say one had it less worse than the other (although the body count appears to be greater on the Stalinist left, and economically Germany has been in much better condition post-trauma) — alas, ancient Greek morality is not authoritative. I mention the parallels, however, mostly to show how this fractal pattern of polarized violence, observable between the sexes, plays out on a vast political scale.

For those great symbols of evil, Hitler and Stalin, provide modern instances of the same pattern of violence thymic and epithymetic. The right-wing thymic totalitarianism of Hitler will control its population by separating it into types and physically killing the undesirables. The left-wing epithymetic totalitarianism of Stalin will control its population by forcing all types into a singularity and eliminating dissent by ostracization and (literal) famine. The two poles are contained within each other, so there will be much overlap in their methods. The Nazis were national socialists, they said, and, as Chomsky reminds us, Leninism comprised the right wing of Marxism. More bluntly, whether you’re put on a train to Poland or Siberia, the camps or the gulag, you’re either way pretty much done for. But I believe that in the directionality of their vectors relative to the poles right and left, a difference in character can be discerned between the two. Even in the manner of these two tyrants’ suicides, I detect the pattern of thymos and epithymia. For Hitler killed himself by picking up a gun and firing a bullet in his skull, a proper “mean boy” way of doing it. Stalin killed himself, on the other hand, by exiling all the doctors needed to save his life — a real “mean girl” way of doing it if there ever was one!

But I’ve come a long way from American Girl in Italy (the land where fascism was born, poor lass). My hope in outlining the shape of epithymetic violence on grand scales biblical, mythological, and historical is that we could begin to take seriously the dangers of weaponized desire and the responsibility of those who wield it. Weaponized anger, violence as it is conventionally understood, is easily recognized and condemned. As such, however, it is often used as a foil protecting epithymetic violence from criticism, even presenting it as virtuous. But epithymetic violence cannot be understood as morally superior to thymic violence. They’re just two poles of the same magnetic field. The West, for example, has been blasting Russia with an undercurrent of epithymetic drag for decades, while on the surface pretending to be all innocent, no matter how many promises to restrain NATO encroachment have been broken. In Ukraine a line was crossed, and Russia has responded, above the surface, with thymic attacks of despicable violence. I condemn both attacks, but I can also plainly see, because I’m amphibious, who the original aggressor is in this particular contest. Those who against all reason continue to justify desire as an absolute good will no doubt disagree, but I can’t unsee the anger residing within lionized desire.

The aphorism, “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them; women are afraid that men will kill them,” represents to me the limits of feminist understanding, which is to say epithymetic understanding. There’s nothing untrue in its parts, and yet the balance of truth in its whole is tragically upset. The contrast between women laughing and men killing is meant to dismiss the fears of men and lionize the fears of women. As a result, thymic violence is persecuted as it undeniably should be, but strategically so as to distract similar attention away from epithymetic violence, the danger of which is dismissed. And with the danger of epithymetic violence dismissed, it can even be encouraged. Desires proliferate madly, our identities become rooted in them, and soon we are teeming with overweening epithymetic whirlpools of suck engulfing our culture, not only inciting wars on our borders without ourselves understanding why, but dismantling us from within by deteriorating our values — any values we’ve held in the past, sure, but also our current epithymetic values, which out of unbridled appetite riotously devour themselves, turning into vicious acts of anger.

I speak, for example, of the ridicule, the scolding, and the ostracizing that have come to predominate media discourse to a highly irrational degree. Arguably it all began with The Daily Show and Jon Stewart’s pivot from the nihilistic satire of the ’90s into the righteous mockery of the Bush administration’s thymic belligerence in response to 9/11. But before I go on tracing this century’s history of ridicule beyond that point, you can already see it’s all a chain of reactions entailing the failure of epithymetic virtue and thymic virtue both. I could cite the 2011 White House Correspondents’ Dinner where President Barack Obama and comedian Seth Meyers ruthlessly mocked a present, not yet president Donald Trump. The satire was as savage as it was on point; Trump was receiving in kind what he had been dishing out with his fascist-style insinuations of Obama’s supposed Kenyan birth. So how does Trump respond except by becoming a full-blown insult comic weaponizing mockery and shame to win elections in a country that champions epithymetic violence? The epithymetic left loses its mind during the Trump years, parallel to how in the ’90s, when Clinton adopted Reaganism to defeat the Reaganists, the Gingrich-led thymic right lost its dialectical bearings and fell into the very nihilist pit from which Trump would later emerge. What foul beast will emerge from the vortex we’re now in? Well, the unveiling effect of a highly contagious airborne disease caused us to have a glimpse. Witness in this video (the whole thing; it tells a story with many acts) the self-inflicted epithymetic violence that can only be called dystopian because hitherto that’s the only way we’ve ever identified this type of behavior. What caused this response in us?

Epithymetic ridicule (think Charybdis) sure can spit out some fascist-style scapegoating once it swallows its abhorrence of dissent with this degree of vigor.

But enough. I keep getting distracted by the political scale of my theme. I need to bring it back to the personal. It appears from the popularity of the Atwood aphorism that women have ceased being able to perceive the fears of men except superficially. That suggests to me they have also fallen away from cognizance of the source of masculine identity, the feminine threat to which causes that fear. And if such a schism between the sexes has taken place, it could only be for two possible reasons: Women have ceased loving the men in their lives, preferring themselves instead, and thus losing familiarity with them. Or else, perhaps, say… fathers, brothers, husbands, and boyfriends have behaved so terribly, so selfishly, as to obscure entirely from vision the sacrificial purpose of their being. Undoubtedly both can be observed. It makes sense that epithymetic and thymic vice would move together in a co-dependent relationship. As to whether one is responsible for inciting the other, it sure seems to me that men were in charge and they led the way. I’ll leave it to a woman to cite Genesis 3 and Patitsas’s beauty-first psychology to argue to the contrary that her epithymetic sex is in fact the original offender. As a man I’ll cite Paul’s teaching that man is the head of the woman and lay responsibility at his feet (cf. 1 Cor. 11:3).

Surely we shouldn’t be blaming each other. At least I know from Genesis 3 that I shouldn’t be blaming the woman! That means we should each take responsibility for our failures — and should seek each other out who are of like mind in doing so, because repenting is not easy, accepting the consequences of our shortcomings is not easy, and we all need lots of help. But these consequences I mention might entail being deprived of any partnership. In such cases we must go inside our heart and realize the implication of these lessons within. Because of course, as throughout this whole essay, I speak of the sexes typologically. That which is feminine within you has to find a path to obedience amongst the crowd of false, sometimes seductive, sometimes threatening principalities God has arranged around you for your correction. That which is masculine within you has to die daily for others, loving as Christ loves, even when His bride gives Him nothing but rejection and ridicule for His sacrifice.

To this end, an aphorism has occurred to me in the past, one I’ve yet to find a use for, but it might be the remedy here. It goes, “A man’s not a man unless he’s providing for a woman.” I think it works anagogically for monastic and single men just as well as for husbands. Relative to God every soul is feminine, and men who, in the context of their relationship with God, provide for their feminine souls with acts of Christ-like sacrifice fulfill the meaning of the aphorism just as easily as those of us married to women — which is to say not easily at all, not in the tiniest little bit, but God must think we’re up to the challenge, which is quite the compliment. Anyways, I like the aphorism because it puts the onus on men to take action, and I think it thereby makes men attractive to women, which over time could solve that half of the problem as well, doing so without any force, which is the only way to awaken desire reliably. Then once women come to love men again, their ignorance of them would be absolved and many knots would be loosened.

For the women who love the men in their lives are not blind to the predicament men find themselves in. They see the relative disposability; they mark it well. And they recognize in it an endearing expression of their own doomed fate. The sacrifices their mortal men then make for them, to protect them, to provide for them, fill them with immense humility and gratitude — and devotion of a tenacity so fierce it surprises the men who discover it and fills them with the fear of God. Then these men’s fear concerning women is that they themselves could ever, even for a moment, betray their women’s love. And so they never do, even if it means giving their life.

This is the meaning of Christian love. And this is how it manifests between the sexes: a holy fear and a holy love. A death, and a resurrection. A cure for all mortality, and a rescue from disposal.

And an Ascension! I greet the Orthodox among you on the feast. And this weekend, have a peaceful Memorial Day, those of you from the States like me. In case you need a palate cleanser after the video of dystopian madness I linked to above, enjoy this Vietnam-era song by Tim Buckley. Please everyone keep in your hearts the lives of those men who have sacrificed for you.

“Once I Was”

by Tim Buckley

Once I was a soldier

And I fought on foreign sands for you

Once I was a hunter

And I brought home fresh meat for you

Once I was a lover

And I searched behind your eyes for you

And soon there’ll be another

To tell you I was just a lie

And sometimes I wonder just for a while

Will you ever remember me?

And though you have forgotten

All of our rubbish dreams

I find myself searching

Through the ashes of our ruins

For the days when we smiled

And the hours that ran wild

With the magic of our eyes

And the silence of our words

And sometimes I wonder just for a while

Will you ever remember me?

Margaret Atwood, “Writing the Male Character,” Second Words: Selected Critical Prose, 1960–1982 (House of Anansi Press, 1982), p. 413.

This might be my best chance to talk about it, so let me just say that the movie Jennifer’s Body, written by Diablo Cody, a camp horror film offering tremendous insight into the patterns of feminine violence, situates its action in a small town the main attraction of which is an insatiable, bottomless whirlpool the physics of which scientists have never understood. It’s brilliant.

This is excellent, Cormac Jones, I really appreciate you writing this, a topic very important to me personally and I think describes a lot going on today which I have wished to say half as clearly. I'm particularly struck by how much of the power of this "epithymetic violence" (a new term to me) lies in its concealing itself, resisting being named, addressed, opposed - even hiding behind the thymic violence, which I think I have always been careful not to downplay.

The whole first paragraph under the header "Epithymetic violence" just about sums it all up to me. It is more or less what I was trying to say in my last piece: "'Lost boys' and the shame of naming the shame": https://njadadetrans.substack.com/p/lost-boys-and-the-shame-of-naming

I'm really not sure how successful I am yet at explaining these things though.

I find myself wondering if it's even possible for society to collectively recognize these dynamics; I sometimes feel a bit despairing about it simply being the stubborn way of the world, that it's very nature is to stay hidden and to thrive off of being hidden. But I'm noticing: Isn't it obvious why feminists reserve the harshest insults for anyone who starts approaching the things you're pointing out in this piece? I don't know if these dynamics will or won't change, but either way I've realized how much I need to detach, for my own sake, from the fear that this or that woman might ridicule me or accuse me, to know more intuitively and immediately that she's not automatically better than me, and to not let the fear put me on guard as if women in general are feminists (or that, of course, all feminists are equally immersed in this mindset). Relatively few women feel bold to speak against something proposed as feminist, but I don't blame them; I don't feel bold yet either. I have to be able to keep things in perspective first, not get shaken out of my wits and feeling obligated to agree with women if something I think upsets them. That's what most important, being able to hold my own perspective on things, not figuring out how to change how others see things, especially not feminists. But that doesn't mean going it all alone, but to be close to others who already can get it, instead of trying to make people get it.

And again this quote:

"Weaponized anger, violence as it is conventionally understood, is easily recognized and condemned. As such, however, it is often used as a foil protecting epithymetic violence from criticism, even presenting it as virtuous."

But it's this impulse to detract, marginalize, alienate, etc., that can be deadly, and far from most women are like this, but there are these dynamics that make men more vulnerable to social types of attacks that we cannot as easily defend ourselves from, that makes it a murderous kind of impulse. Cutting a person off from community cuts them off from a livable life. It cuts off in many cases all hope of resolving personal struggles, no matter how big or small; small problems, if completely irresolvable, become big problems.

Especially when this impulse is taken out on young boys in anticipation of their becoming grown men, it's like condemning them to a living death, possibly even living believing it was necessary, feeling it was deserved or thinking it was their own idea (being "one of the good ones"). And I can already hear the feminist in the my conscience going: "How dare you try to liken that to murder!" but I have to leave that be.

And now that I connect the Atwood quote with this alienating attack, yes, it's much more meaningful than it looks at first. It seems to show how morally superior women are, or that they can only do so much harm, whereas men's harm goes to the very limits. But as you say, the aphorism "represents the limits of feminist understanding" and not the limits of women's understanding. And this reminds me not to take feminist criticisms as so authoritative, they just one voice among many, they'll have their points, but they so often thrive by passing themselves off as immediately obvious and just any decent person would surely agree, and I have to not get shaken up by that and just recognize it for what it is. I just gradually become more aware of this kinda stuff over time.