The dialectic of Western politics is patterned after the corruptive polarity of desire and anger, and it’s killing us

How concise a political treatise can I write? More concise than this headline perhaps? Please?

Contents:

I. The Church’s tripartite psychology

II. The pattern of epithymia and thymos in the world and in the mind

III. The politics of left and right

IV. Anxiety and depression vs. prayer and fasting

V. The end of democracy, and quixotic voting

I. The Church’s tripartite psychology

I’ve lost track now how many times I’ve treated this topic: the Church’s tripartite psychology. I feel like I’m always rehearsing this exposition, trying to get it right from a didactic perspective. Those familiar with me may not need to hear this again, but for the sake of more recent subscribers, and anyone new this essay might reach, I’ll start with the basics in an attempt to create something a little more self-contained, notwithstanding a stray hyperlink here or there.

The Greek Church Fathers, though steeped in the spiritual praxis and theoria of biblical revelation, yet found Greek philosophical terminology, which arises from natural law, very useful for explaining more logically how the soul works. The English word tripartite (trimerēs in Greek) gets used to describe the three “parts” of the soul, but they’re not parts as such (as if the soul were composite), more like faculties or powers. This is how the soul is observed to operate: On one hand there is an appetitive power, epithymia in Greek, functioning like an attractive force pulling that which is desirable toward the soul. On the other hand there is an incensive power, thymos in Greek, functioning like a repulsive power pushing that which is abhorrent away from the soul. These faculties are also called passions in that they are sources for the soul’s passivity to external forces; in the corruption common to all of our experience, these two lower passions, attractive and repulsive, are observed as desire and anger — which indeed are the respective vernacular translations of epithymia and thymos.

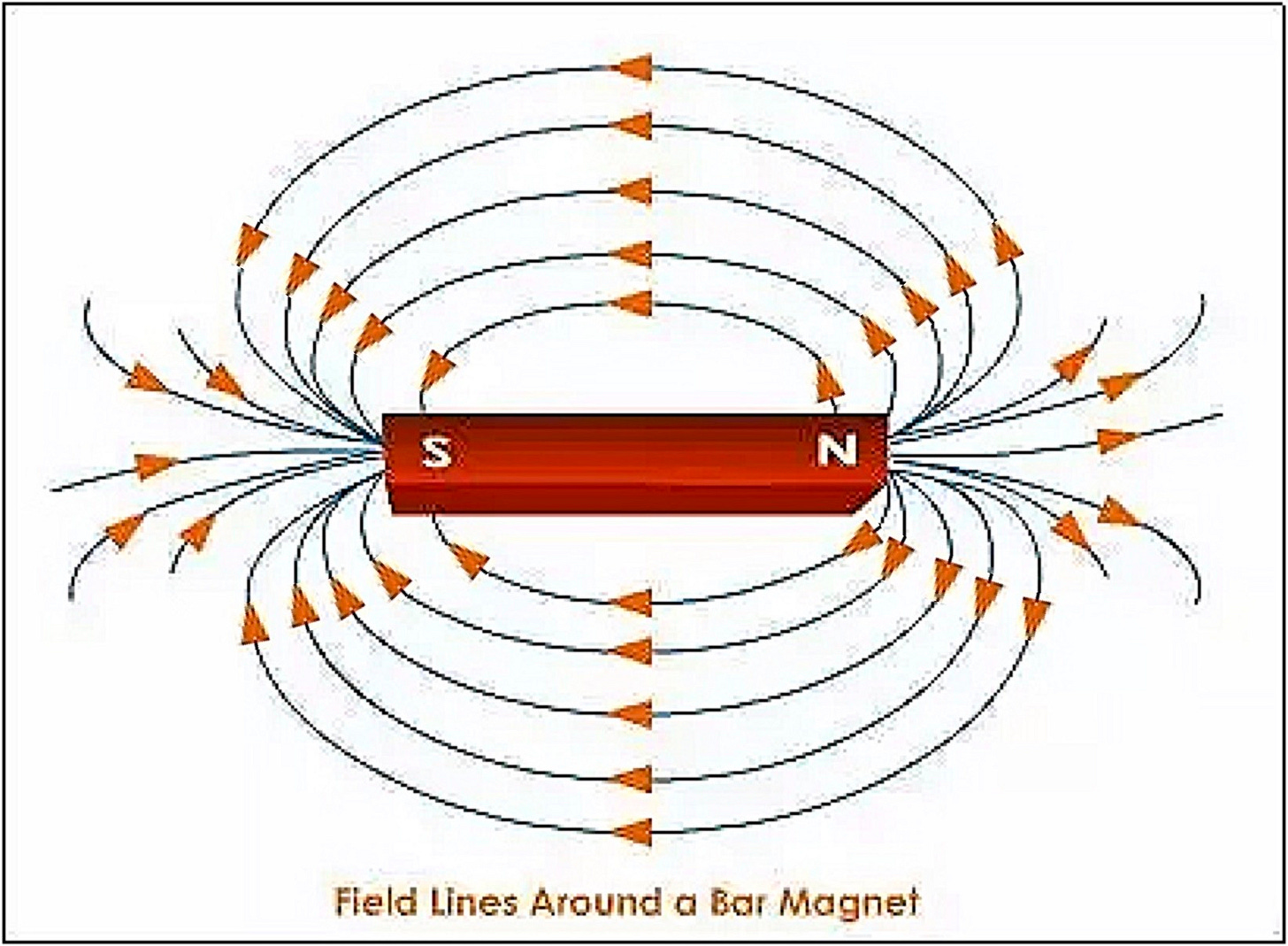

The way these two powers, desire and anger, work in tandem is like the two poles of a bar magnet. This analogy will be especially relevant to our political discussion. At the south pole of a magnet, the magnetic vectors are directed inward; this represents the appetitive, desiring aspect of the soul. At the north pole, the magnetic vectors are directed outward, representative of the incensive, striving aspect of the soul. Relative to the magnet, the two poles appear to be in opposition to each other. Viewed objectively though, they are observed to be not only working in cooperation with each other, but in fact identifiable as one and the same magnetic field.

Hence, for example, the holy Abba Dorotheus of Gaza (6th c.) writes, “Anger has diverse causes but the principal one is love of pleasure.... One of the holy fathers used to say, ‘The reason why I turn away from pleasures is to cut off occasions for getting angry.’”1 Whenever material desire throbs within the soul, somewhere nearby anger will be found throbbing in stereo. For one thing, any addiction to sensual pleasure will naturally be accompanied by an aversion to the deprivation of that pleasure. Cupidity and wrath — like decadence and tyranny — are contained within each other.

Dispassion towards pleasure and pain, then, is certainly a goal. Our worshipful attention to created things is what engenders the throbbing passions of pleasure-seeking and pain-avoiding (attraction and repulsion). Thus, recommending this dispassion is no different from the first of all commandments, that is, not to worship created things in place of the Creator. Such psychological health is achieved not without the means of reason — logos in Greek — the faculty of the tripartite soul which is supposed to rule over and provide meaning to the other two. The whole point of this essay, and others like it by me, is to exemplify this governing, ordering action of logos. Plato, to whom all this terminology can be traced (if not its perfect understanding), describes the lower passions as the two horses of a chariot, and reason, logos, as their charioteer. The Church baptizes this imagery in her prayers by relating it to the chariots of Pharoah at the crossing of the Red Sea. A common irmos encountered in Orthodox hymnography reads, “Drown Thou, I pray Thee, the three parts of my soul in the depths of dispassion, as of old Thou didst drown the mounted captains of Pharaoh.”2 Having oneself baptized in the Church’s knowledge concerning desire and anger, by reading the Church Fathers and practicing the commandments, exemplifies logos performing its natural function of mastering thymos and epithymia — it is how one is purified of Egyptian corruption and made a true son of Israel.

At the same time, however, we must recognize that dispassion (apatheia in Greek — impassivity) is our goal only in regard to created things. Indeed we are not to be passively moved by created things, but we are to be passively moved by our Creator. Truly we have our origin in this. When God creates us, we are brought passively from non-being into being. Thus in our very nature we are attracted to the divine source of our being and repulsed by the non-being from which we are differentiated. And thus the pattern of a magnetic field with inward and outward vectors occurs subtly in the human soul naturally and by design. Its purpose, the reason this is so, is found when we receive passively from God not only our being but our virtuous well-being — when we are moved by Love to love.

The love for which we are created can be thought of in two different aspects according to the pattern of the passions with which we are familiar in this life. St. Maximus the Confessor (7th c.) identifies the two great commandments, to love God and to love neighbor (cf. Matt. 22:36–40), as applying to these two aspects.3 The inward vectors of epithymetic, appetitive love, also known as eros, are resolved in our love of God. Instead of desiring created beings, we desire solely the otherworldly Creator of our being, locating our true pleasure in Him. Such divine eros is of one magnetic field with divine agape, the outward vectors of neighborly, self-emptying love resolving the passions of our thymic drive. The way our soul’s repulsive power works, for good or for ill, is a bit more complex to grasp conceptually, but it is easily understood in practice because issues of chivalry and manly virtue are direct manifestations of the phenomenon. It’s the difference between a good father and a bad father. A good father is a generous provider and a courageous protector. He uses the outward-facing, striving vectors of his soul to push away all want and danger. A bad father is someone who either out of thymic weakness fails to provide and protect, or, worse, errantly directs his outward vectors towards those under his care, becoming tyrannical and violent — indeed becoming the source of want and danger. In contrast, the agapetic love that fulfills the command to love one’s neighbor as oneself entails an outward striving of self that provides peace and sustenance to others, negating all discord, want, and fear.

Now that I’ve alluded to the connection between the passions and gender, though, it would be a good time to pivot to my next topic.

II. The pattern of epithymia and thymos in the world and in the mind

It was not good that the man should be alone, so God created them male and female (Gen. 2:18, 1:27).

The dynamic of sex in humanity comprises a bodily reflection of the thymos-epithymia polarity. Hence in the rendering of the tripartite soul (at least since Philo, and filtered into the Church through Evagrius) thymos is coded masculine, and epithymia is coded feminine. What are thought of as masculine virtues are thymic virtues, and what are thought of as feminine virtues are epithymetic virtues. Our current term ‘toxic masculinity’, meanwhile, is marked by angry and controlling thymic passions, just as ‘toxic femininity’ is made up of needy and passive-aggressive epithymetic passions. The discipline of marriage provides a path for resolving the polarity of our personalities towards serving God and neighbor. What monastics achieve internally, married folk achieve socially. It is according to the human pattern of soul and body that both paths be integrated in the hierarchy of the Church, making right what was lost in the fall. The logos of sexual differentiation among humans — that is, God’s intentions for creating such sexual differentiation — is precisely so that the human being mediate the gross polarity of material creation with the subtle polarity of spiritual creation so as to make of all creation one unified vessel fit to receive the deifying grace of love, both agapetic and erotic in character.

But a world in accordance with God’s intentions for nature is not the one we’ve been born into. Our mother Eve, in seeing that the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil was good to eat (willingly ignoring the ‘evil’ part) and pleasant to the eyes, sought pleasure separate from pain, a logical impossibility; pain swung back and hard. She was told that as a consequence her longing will be for her husband, and he will lord over her (Gen. 3:16). Thus the natural polarity of the body seeps into the soul, corrupting it, and the polarized, passionate modes of epithymia and thymos erupt, referred to in this verse as longing and lording. St. Maximus the Confessor, for one, is clear that when St. Paul says that in Christ there is neither male nor female but all are one (cf. Gal. 3:28), he in fact refers not to the logos of bodily identity (it is not said ‘neither man nor woman’) but to these septic, divisive modes of the soul that erupted into the world at the fall: anger and desire, the feminine appetite and the masculine aggression.4 This subrational, polarized pattern of conflict visible psychologically in each individual, and then socially between the sexes, goes on to repeat fractally on every level of fallen human activity.

For twelve years, atheist social philosopher Jane Jacobs kept notes on news stories in the printed press, tracking all the moral values she saw either praised or denounced and marking the context in which the evaluations were made. She writes — in her book Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics — about how when you do this, a pattern emerges of two competing sets of morals (which she identifies as syndromes), both of which are essential to the functioning of society but which are eternally at odds with each other. For the success of commerce, one syndrome privileges innovation, openness with outsiders, voluntary agreements, efficiency, honesty, the promotion of comfort and convenience, and optimism. Jacobs calls this the Trader Syndrome. On account of conflicting desires, it cannot survive on its own and requires society to be governed, policed, and protected, for which cause the Guardian Syndrome is called into service. It contrarily privileges tradition, hierarchical loyalty, the exertion of prowess, the distribution of largesse, deception for the sake of a task, displays of fortitude, and fatalism. As for which values each syndrome shuns, just switch the lists; the morals of the two sides are diametrically opposed to each other. Yet each is no less necessary than the other. Applying this lens to civilizations throughout history, Jacobs finds a fit; there are variations in terms of rigidity and flexibility between the two modes, but conceptually, commerce and politics always work this way, in all contexts. When financiers or scientists, who should hold to the morality of the Trader Syndrome, ply their craft with the Guardian Syndrome instead, or alternately, when the military or a regulatory agency takes to the Trader Syndrome, in either case a corruption is in play that is deleterious to public welfare.

Dr. Timothy Patitsas, disciple of Jacobs, covers this content from an Orthodox Christian perspective in chapter seven of his book The Ethics of Beauty. He makes a lot of great points, consonant with my own opinions about politics, but he doesn’t make the connection that I’m obviously going to make here, that the Trader and Guardian Syndromes are just the fractal polarity of epithymia and thymos writ large, the passions of feminine longing and masculine lording. [Edit: He in fact does mention it, briefly, in a footnote that I had forgotten about. My sincere apologies.] For commerce serves the appetites of desire, and politics serve the compulsion to control. I had cause a few months ago to call attention to this iteration of the epithymia-thymos pattern when critiquing John Vervaeke’s video on AI (link). He fell naturally into the pattern of criticizing “the pornographers and the military” (epithymia and thymos, obviously) as immoral motivations for technological development, and at one point those two agents were generalized as the “molochs that are running our politics and our economy.” Politics and economy — it’s the pattern of the Guardians and the Traders. When humans throbbing with the magnetic charge of thymos and epithymia socialize, they naturally arrange themselves in domains that produce a magnetic field on a large scale. And of course the two sides have contradictory moral codes; one pole has the vectors pointing in, while the other pole has the vectors pointing out.

That the two sides each feature a moral ideology complete unto itself and incompatible with the other (which is how Jacobs describes it) calls to mind the state of modern physics for the last hundred years. General relativity and quantum mechanics each describe the universe so cogently that you’d never know either of them didn’t explain everything if not for the existence of the competing theory. And of course the two models are incompatible with each other. One’s positioned at the south pole, with vectors pointing in, while the other’s positioned at the north pole, with vectors pointing out. We gape upwards at the stars we yearn for but can’t control, and imagine a unified cosmos pulled by the attraction of gravity, even to the point of devouring itself. Or we peer downward at the subatomic realm in our hands and calculate a fractured multiverse that appears to be repelled by its own existence at every moment, in every place. In and out, attraction and repulsion — the sepsis of polarization appears to have overtaken even our loftiest mental speculation.

This is how the dialectical thinking upon which science is based works (I began writing on this topic here), patterned after rebellion from God and the polarity of sin. To generate meaning from our impassioned selves, we set things at variance with each other. This variance itself is at variance with itself; it is polarized according to the pattern of deductive and inductive reasoning. At a more granular level, dialectical negation occupies the north pole in its forceful rejection of a thing according to the strength of its opposite (think Parmenides) — while dialectical opposition occupies the south pole by collecting opposites in a mutually affirming spectrum of meaning (think Heraclitus). These patterns of dialectical logic come into play when we consider political behavior, how political opponents strive to negate each other and work off of one another at the same time.

Meanwhile, though, that our very brains work according to this polarity is explored in great depth by psychiatrist and philosopher Dr. Iain McGilchrist. Quite, quite briefly, and in my own words, the attention of the brain’s right hemisphere pulls in the whole environment to gain a general surveillance of its shape and context. The magnetic vectors are all being sucked inward. The brain’s left hemisphere, to gain a more specialized knowledge, focuses on particular items of interest by negating everything they’re not. The magnetic vectors are propelled outward. As I touched upon here, McGilchrist wrongfully interprets this polarity as that between what the ancient Greeks called nous and logos. It could hardly be more manifest to me that the pattern he describes corresponds rather to that of epithymia and thymos, just on a contemplative level rather than a volitional. Already in Plato’s parable of the charioteer (in the Phaedrus), the two horses not only have legs and the charioteer not only has the wheels of the chariot, but all three agents are also depicted as winged, the suggestion being that the tripartite pattern has presence on both earthly and heavenly planes, both in praxis and theoria. In the Church Fathers’ tandem use of conviction (repelling falsehood by means of dogma) and conjecture (gaping for knowledge above one’s reach) I see this polarity put to virtuous use. By reductive scientific means, McGilchrist arrives at the awareness of reductive scientific means’ stark limitations. I think by his own values, formed in the attempt to negate those limitations, the Church’s understanding of the tripartite soul offers the more holistic rendering of the neurological pattern he describes — even if in his scientific approach he has found a shortcut to greater specificity.

But it’s time now to talk about one of the most obvious ways the polarity of the passions rules the world and infests our minds.

III. The politics of left and right

In the beginning was George Washington. He was a young land surveyor in the British colony of Virginia who sought rank and wealth, the former for his thymos and the latter for his epithymia. Rank was strived for by means of the military, namely the Virginia Regiment, and wealth was sought by means of the Ohio Company, a land speculation business. Both appointments were received from Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie, both the head of the Virginia Colony (a guardian) and a prominent stockholder in the Ohio Company (a trader). Both as a commanding officer of the Virginia Regiment and a representative of the Ohio Company, George Washington at ages 21–22 traveled to the region of modern-day Western Pennsylvania to secure the imperial borderland from French incursion and to claim choice plots of land for himself. Exhibiting poor leadership and bad tactical decisions, he presided over a disastrous skirmish that incited the French and Indian War and then was badly humiliated in the follow-up battle. He would go on to fight more for the British, but had to resign for a time to avoid demotion. His objective in the Virginia Regiment was not to stay in that rinky-dink colonial outfit, but to receive a royal commission and the social status that came with it. That never happened — a slight not just to him but to all the American colonies. The eventual British victory, which Washington had nothing to do with, did, however, secure his land claims from the grips of the French. After the war he married a rich widow, got elected to colonial government by bribing voters with liquor (not an unusual tactic at the time), and used deceptive means against his fellow veterans to expand his land claims in the Ohio Country.

British land claims in the Americas were originally known collectively as Virginia, and the first colony to take root, Virginia, had its origin as a company in search of wealth. The foundations of some subsequent colonies were motivated by religious factionalism, but the appetites of commerce and a mercantile economy remained the common source of British presence on the continent. Yet, as colonies, they were subject to the despotic rule of the crown. The French and Indian War between the empires of France and Britain morphed into the Seven Years’ War in Europe and attending colonies. Indeed it was the first global war; Washington started it amidst the tributaries of the Ohio River, and it wasn’t resolved until news of the Treaty of Paris reached the Philippines. When the British won, its global territories ballooned to an enormous size, unprecedented in world history. But then it came time to pay for the war — and for the upkeep of its oversized empire. Taxes had to be levied. The king came down especially hard on the American colonies where it all started.

But many Americans, like Washington, fought the war for rank and wealth. Lacking rank in the crown’s eyes, they take offense to being asked for their wealth. Thus my nation’s War of Independence takes on the tenor of the Trader Syndrome, marked by commercial appetites, attempting to shake off the control of the Guardian Syndrome, and any thymic discipline that comes with it. For example: General George Washington, having done nothing but fail in his military career up until this point, wins the war against his sovereign king and the almighty British (thanks to his hitherto enemies the French) and amasses sufficient political capital to name himself the Caesar of America. Instead he does something even more impressive (and of incalculable historical significance): having amassed all political power unto himself, he hands it all over at once to a civilian congress and retires to manage his property. The south pole here is really trying hard to detach itself from the north pole.

But you know what happens when you try to sever two poles of a bar magnet? Break a bar magnet in half and you don’t get a south pole in one hand and a north pole in the other. You get two magnets — remember the poles are contained within each other. Break the south pole off in your left hand, and a new north pole appears out of the freshly severed end. The magnetic field does not disappear; it multiplies.

The colonies win the Revolutionary War, see, but then it comes time to pay for it — and for the upkeep of their huge new federation. Taxes have to be levied, again. Washington meanwhile has been drawn reluctantly out of retirement from public service to be the democratically elected president everyone can agree on, and his Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton cooks up a whiskey tax which hits the Appalachian frontier absurdly hard. People out there ignore the offense, and for years tax collectors don’t even try to enforce it. Many of these frontiersmen too fought in the War of Independence, and it wasn’t so that they could be taxed of all they had by a distant government that does nothing to help them — quite the opposite. It should be borne in mind also that these Appalachians know Washington not just as the heroic general but as a cruel absentee landlord who would send out strongmen not to work his land but to evict impoverished squatters who do.

So the Trader becomes the Guardian. The government needs the money. Washington marshals an army and leads them himself against his own rebelling citizens — those who arguably are in the same position he was in but fifteen years prior. The so-called Whiskey Rebellion is immediately squashed with little fighting, just a huge show of force. The polarity of longing and lording is inevitable in this fallen world.

But Washington still intends to refuse absolute power. Though the federal Constitution places no term limits on the office of president, he steps down after two terms. In his farewell address, he sternly warns against the formation of factional parties. No one ever takes this seriously. Just to ratify the Constitution, the erstwhile confederation already had to form into federalist and anti-federalist camps. Washington, while he rules, recapitulates and holds in balance the polarity within his administration — but as soon as he’s gone Vice President John Adams and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson are naturally set at variance with each other, unleashing the horses of polarization from the grip of any charioteer. Adams represents the Federalist North and Jefferson the Democratic-Republican South. As such they behave as thymos and epithymia respectively, but the poles are contained within each other. The imperious, thymic North rules by means of commerce; their power source is the appetite of industry. The South, which relative to the North is freedom-loving and epithymetic, internal to itself is based on the domination of aristocracy and slaveholding. The polarization of desire and anger emerging from the fallen human soul saturates the entire political structure on every level. It at once tears the soul of the people apart, and holds them from escaping the agony.

Like the years-spanning montage sequence in Idiocracy, fast-forward to the present era.

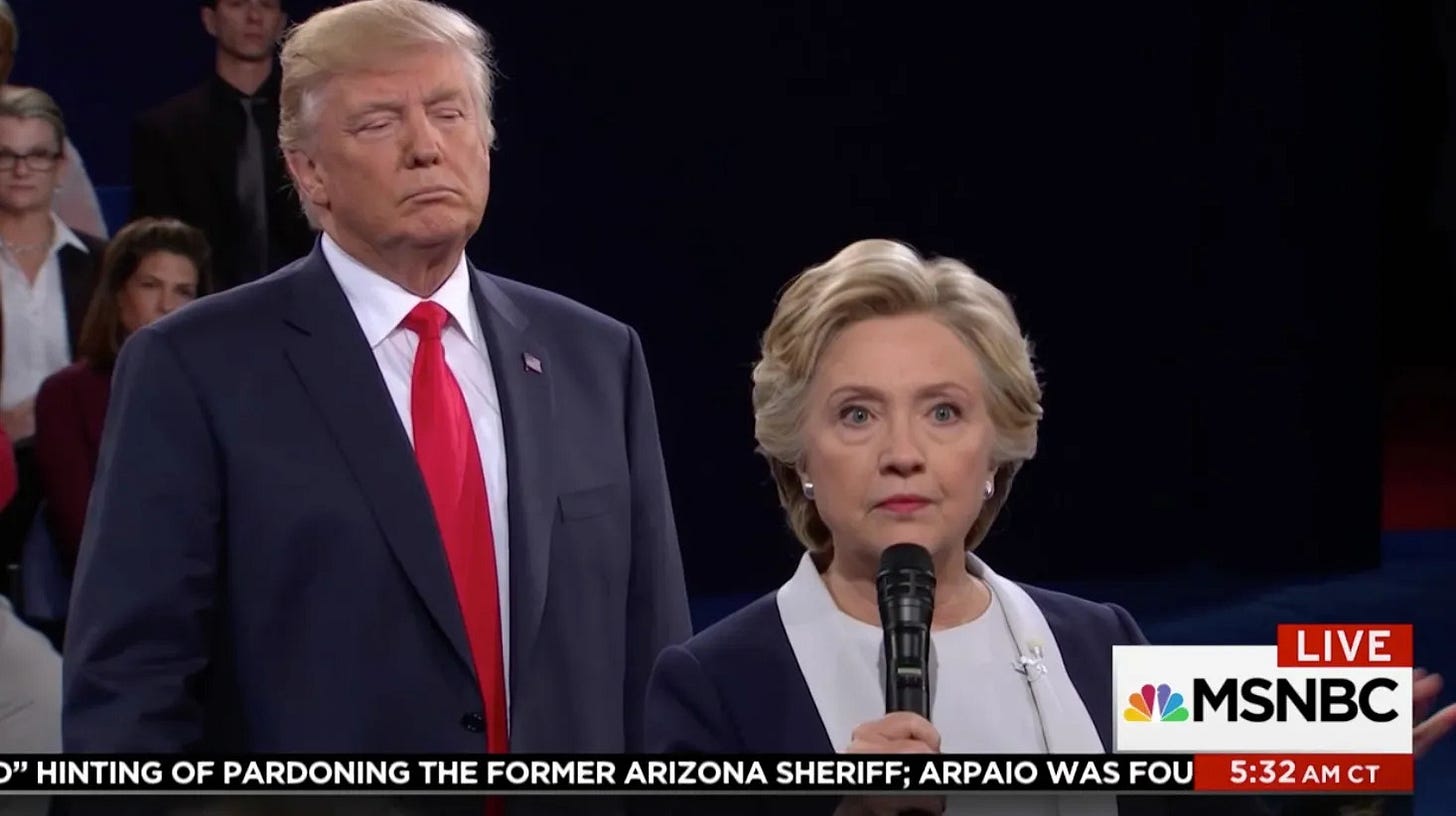

In Western politics, epitomized by the United States with its two-party system, relative to each other the left behaves as epithymia and the right as thymos. On the issue of immigration, as a quick example, the right will emphasize that theirs is a nation of laws; foreign bodies must be tightly controlled and their influx limited so that national identity can be clearly defined and maintained. Maintaining national identity doesn’t mean anything to the left, though, if it doesn’t stress hospitality to outsiders and inclusion of the marginalized. And so on this issue the left will emphasize sympathy towards immigrants, especially refugees and asylum seekers — even at the potential cost of not maintaining a national identity that stresses hospitality to outsiders and inclusion of the marginalized. Anyone can see that an absolute position of either open or closed borders doesn’t work, yet any politician can rally his or her partisan base by pumping the outward thymic vectors of the right or the inward epithymetic vectors of the left, regardless of what proper mix of the two impulses is called for.

Now, the poles are contained within each other, of course, and in America in recent years a schismatic break has formed exposing each sides’ butt ends to each other. The left has been manifesting the totalitarianism of desire, intolerant of dissent, while the right’s quest to “own the libs” has them behaving like so many smitten schoolboys angrily picking on the pretty girls they’re uncontrollably attracted to. Butts acknowledged, it is yet incumbent upon me to spend more time describing the faces of left and right, and how they fit the pattern of desire and anger.

For this cause I wish to discuss the media. Media and politics themselves have an epithymia-thymos patterned relationship. The media with its 24-hour news cycle is driven by its incessant appetite for content and attention. Politics is conversely occupied with obtaining and maintaining power over others by legislative, executive, and judicial means (or martial law if necessary). Like wife and husband, politics may be the head of the household, but the media is the neck — she fancies she can turn politics in any direction she thinks best. Together the two spouses comprise the poles of a single axis, with the media being the most common way people interface consciously with that axis. But the pattern is a fractal, of course; there are right-wing and left-wing politicians, and there are right-wing and left-wing media. So let’s consider the genres of media where the fractal pattern of polarization is most evident: late night comedy and talk radio. Again, this narrative I’ll lay out has been complicated in recent years by people’s butts getting in the way, but hear me out.

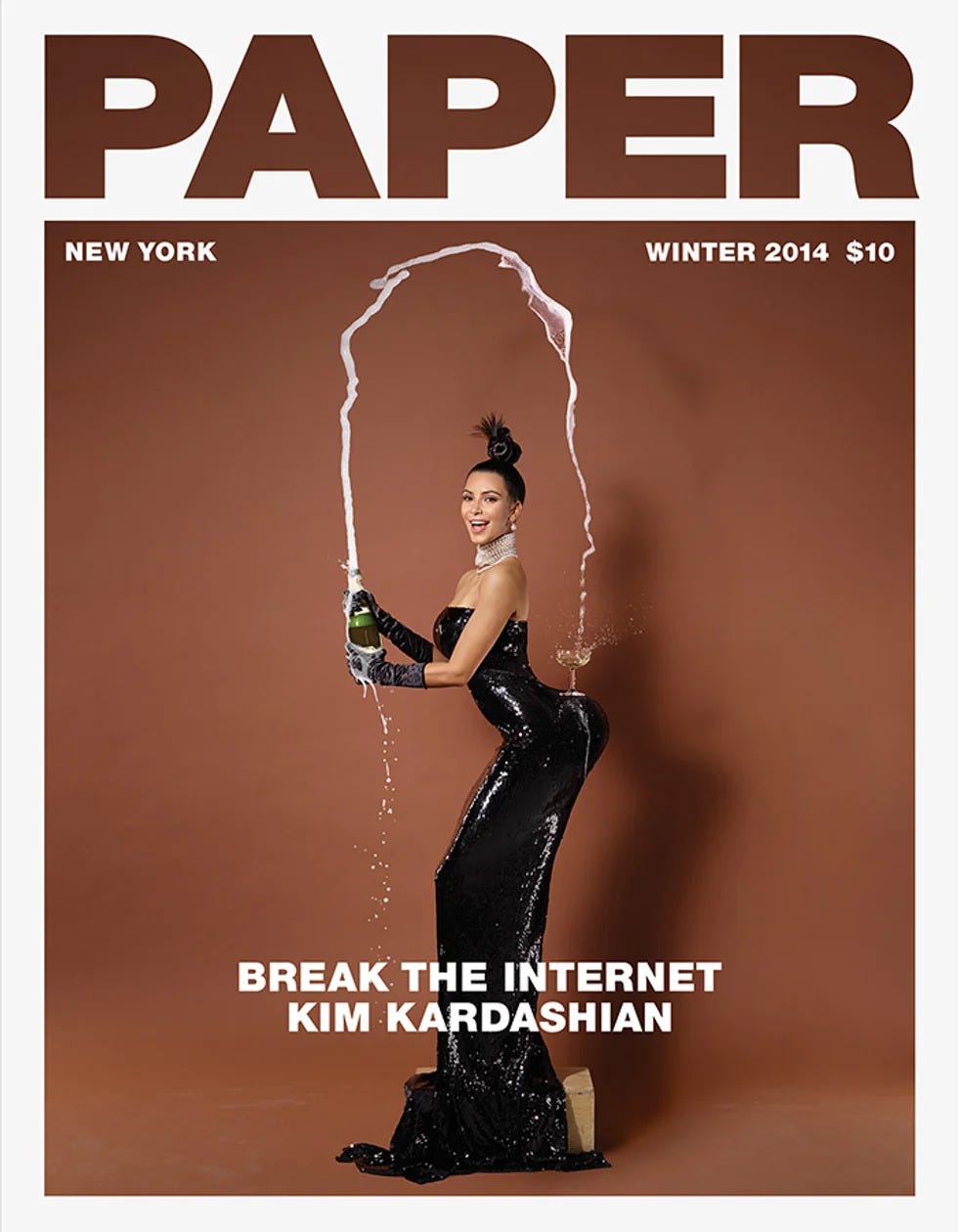

Late night comedy is dominated by the political left. Clearly there is something about the genre which fits the magnetic vectors of one pole and not the other. First of all, it is bound to be political because of the daily need for new content and attention. Comedian Pete Holmes actually once had a show after Conan where the monologue consisted of entirely non-topical, non-political, observational-style stand-up humor. It was an impressive feat to do that for four nights a week, but it did not garner much attention — it had no magnetic charge. For that you need to comment on the news, which is political. But it has to be humorous. Humor is pleasurable and builds camaraderie. A late night host tells a joke on a political topic, and the audience is thus invited to enjoy the warmth of inclusion in an in‑group. It will come at the expense of anyone with differing opinions, thus yielding an out-group as well, but the face of the project is fostering pleasure. Naturally these magnetic vectors are suited to those on the epithymetic left.

Talk radio, on the other hand, exemplifies the other end of the axis. As soon as the FCC canceled its Fairness Doctrine in 1987, which had artificially balanced political opinions expressed on air, right-wing voices like Rush Limbaugh (the most popular one of many) took over the airwaves and dominated the medium the way satire is dominated by the left. In the format of talk radio, without anything beautiful to look at or hear, indignation rather than pleasure drives audience attention. The magnetic vectors match those of thymos, and thus right-wing politics dominates; it too is thymic in character. The power of negation is the draw — of creating an out‑group of disorderly, entitled freeloaders with no respect for authority. Incidentally, in striving to exert power over an out‑group, the talk radio audience also enjoys the righteous warmth of being in an in‑group of strivers, just as the late night TV crowd doesn’t mind the power of scapegoating an out‑group while they form their cozy, equally self-righteous in‑group of empaths. The poles are contained within each other. But faces and butts can be discerned as inversely arranged on the two opposing sides.

Nowadays, though, when everyone’s a buttface, I admit the narrative I laid out is less clear. The explosion of podcasting in the Trump-Biden era has threatened the subsistence of radio stations themselves to say nothing of syndicated talk radio, and the earbuds of liberals and progressives have never been so glutted — or so motivated by anger. Remember after 9/11 what happened to Dennis Miller, who throughout the nineties was bracingly hilarious, but who then became an explicitly right-wing comic and was immediately, startlingly unfunny? That is what has happened to all late night comedy hosts since Trump’s rise to power. Their audience is fueled more by the outward vectors of indignation flowing from their butts than the junk food humor they stuff in their smiling faces. Right-wing comedy, meanwhile, is probably better than it has ever been in America, which truly is not saying much (anti-communist satire in Eastern Europe is on a whole different level). It doesn’t have to be great, though, because there are plenty of comics now who have been out‑grouped by the freshly sanctimonious left for merely staying faithful to the spirit of satire, who, though their political sensibilities haven’t changed, can now be safely enjoyed by buttfaces on the right without breaking their out‑group/in‑group directionality.

The issue of sanctimony and the intolerance of wrongthink will help me pivot away from the subject of media and towards that of political opinion. The way those two qualities have migrated from the right’s face to the left’s butt in my lifetime has been a remarkable occurrence. The way I think it has happened has to do with the gravity of epithymetic desires towards the body as the teacher of pleasure. The left with its inward-facing vectors will naturally prioritize the pleasure of inclusivity for the sake of camaraderie and completeness (as opposed to entrepreneurship and individualism). But its virtues of inclusivity and diversity come to be defined solely and rigidly according to the body: sexual identity and orientation, skin color and race, various disabilities — all products of materialist causes rooted in the body, as if the body is all-important to human identity to the exclusion of anything else. Other definitions of inclusivity, and of human identity, based not on the body but on the soul, particularly regarding ideological diversity, are proscribed and subjected to intolerance. Love of the body has turned identity politics on the left into strictly body politics. The political left is commonly defined psychologically as curious and open to new experiences, very epithymetic traits, as opposed to the right which thymically emphasizes law and order and respect for authority (Jonathan Haidt, for one, has gone over this a lot in the past). But people who are more open-minded ideologically are these days suddenly, sometimes uncomfortably, more welcome on the right than on the left as the right opportunistically stresses the values of free speech inherent in its individualism. In a previous generation, though, threats of censorship were more likely to come from the right as it strove thymically to control morality.

I suspect they will again one day, for that controlling impulse of the right is still very much active in regard to issues like immigration (as I’ve mentioned), entitlement programs, government budgeting, and abortion. Likewise the left has maintained its desiring impulses on these issues. The faces of the two poles are clearly discernible here. When sex is understood as a pleasure activity, abortion must be permitted; when it’s understood as the mechanism on which families and nations are built, abortion must be strictly regulated if not outright forbidden. Those aren’t the only thoughts possibly to be had in regard to abortion (I know Christians have more to say here), but under the yoke of polarization those are the only actionable political ideas. In the predominantly epithymetic culture of America, meanwhile (due to its history as commerce-focused Traders ripping themselves from Guardian control), popular support for abortion access is going to predominate, as it does now, many on the right siding with the left on this issue, opportunistically basing a pro-choice position on individualist morality. Efforts of a pro-life minority to institute legal solutions to this spiritual problem are likely only to backfire. Trying to change hearts with laws, or instituting laws as if people don’t have hearts to change, cannot work.

Squaring pro-life support with overabundant military spending is also hard to do from a humanist perspective, but it makes sense on the right where both are about control and national might. Whenever not in power, right-wing politicians in America have often pressured their left-wing opponents on the issue of government overspending. Back in the day Bill Clinton played a mean trick on his adversaries by following through with their demands and actually balancing the budget. He was a better Reaganist than the Republicans (including Reagan) — who when in power have never limited their appetite for overspending. The difference is they spend on the military instead of entitlement programs. The plain truth is they’ve only ever cared about debt and deficit when they can use the complaint to leverage the thymic drive of voters against epithymetic politicians. All the right knows how to do is strive for power. Providing for the citizens’ needs where commerce fails them, and indeed, threatens their welfare, is just not in their tool kit — despite that such provision and protection should be a virtue of thymos in a healthy soul. In the 115th Congress of 2017–2018, the Republican party controlled the White House and a majority of both chambers of the legislature. After eight years of obstructionism under Obama, this was their chance to show what they really wanted to do with all the power they demanded for themselves. Their major accomplishments were transforming the judicial branch in their image, so as to extend their power beyond their term limits, and legislating a tax break for the donor class, so as to support their future campaigns. They said at the time they intended next to give a tax break to the middle class. As it happened though, they only had the political stamina for one round of cuts, and the one they did first was apparently what they cared about most. Besides those two things, these Republicans also made an unholy mess of immigration, cracking down on airports and southern border security in the most sensationalized ways possible, such that it rallied their opponents and for a stretch of three days brought the government to a halt — despite Republicans holding all branches of government.

Calls to “repeal and replace” Obama’s Affordable Care Act, meanwhile, a grassroots rallying point under the previous administration, went absolutely nowhere because the party had absolutely no functional healthcare policy ideas. Like a bad father, actually providing for the needs of the household they felt entitled to control was completely off their radar. They have in effect ceded the issue of healthcare reform entirely to the left, leaving the left’s appetite for entitlement programs to feed into the healthcare industry’s appetite for commercial surfeit, exploiting the populace’s unending appetite for pleasure-seeking and pain-killing. Epithymia rules the day on all levels of society, but with an orgy of pleasure comes a plague of pain. In Greek, orgy means wrath.

The epithymetic West does not want to understand this and, like a street gang of drug dealers, lionizes desire on every corner, ignoring the violence of anger contained within it. The illegal drug trade works this way — the legal drug trade works this way. All impassioned Western culture works this way. The culture-wide epithymetic suck has, through the power of magnetic polarization, caused the war in Ukraine on the West’s border — which is not to absolve Russia for agreeing to be the north pole of anger dialectically propping up the West’s south pole empire of desire (I wrote about this here and here). If only Putin would refuse to play the bad guy, we would eventually be dialectically compelled to recognize that the bad guy is us. It’s flatly astounding how critical the left can be of all past Western imperialism, when they are the ones spearheading all present Western imperialism. But that’s how Western imperialism proceeds through history, by means of dialectical polarization. You might also say it’s astounding how antipathetic the right is to the present incarnation of Western imperialism, given it’s the natural development of past forms upheld by the right — but it’s not clear how antipathetic they actually are.

Seeds of rebellion against this empire I think can be found in Oliver Anthony’s overnight hit song “Rich Men North of Richmond,” though there are also signs in it of just another doomed Whiskey Rebellion. I find old school leftist Billy Bragg’s response to the song telling. Writing in The Guardian, he describes first listening to it and being enthused as long as Anthony is lamenting rich men having total control and making working folk’s lives miserable. But then in the second verse when Anthony contrasts “folk in the street” who “ain’t got nothing to eat” with “the obese milking welfare,” Bragg’s enjoyment derails, and he wonders if he’s hearing a parody song. I agree these lyrics are not gracefully composed, but they come from an experience that a lot of people share. When he sings, “If you’re five-foot-three / and you’re three hundred pounds, / taxes ought not to pay / for your bags of Fudge Rounds,” I don’t think he’s arguing against welfare in principle; why else would he be complaining that “folk in the street ain’t got nothing to eat”? Rather, I believe he’s protesting against the world of pain contained within addiction to pleasure, of which he and millions of people responding to the song know firsthand (see the line “and drown my troubles away”), as well as against “rich men” weaponizing our desires against us as a means of total control (recall how young George Washington first got elected to colonial government). The system is broken, he is saying, and rich men are taking advantage. Bragg calls out “libertarian billionaires” in his answer song, but in fact since his heyday in Thatcher’s era, the West’s wealthy have moved noticeably from right to left. More and more, power is in the hands of those exploiting epithymetic, communitarian politics, not libertarian. Criticizing desire like Anthony does, however, diverges sharply from the moral tunnel vision of the left and is the quickest way to set them against you, marking yourself as right-wing in their eyes whether you agree or not.

Bragg’s lyrical solution to Anthony’s woes, derived from dialectical materialism, is, of course, “Join a union,” which indeed can be a relatively positive use of thymic striving within an epithymia-dominated mindset. In context, though, it sounds to me, albeit unintentionally, like a sly reference to the Union (capital-U), in opposition to Anthony’s sly reference to the Confederacy, that bastion of anti-federalism, the capital of which was Richmond. What, are the rich men in Richmond not worth our ire? The powers that be south of Richmond, they’re all okay? This is where I see Anthony not evading the game of American dialectic. But to the anti-federalist minstrel, Bragg responds, “Join the Union.” It’s as if to say, Play the materialist game; demand your rights. I think what Anthony sees that Bragg doesn’t is that the materialist game of rights and appetites is captured by the tyranny of desire wrecking our lives. Relatively speaking, yes, the young union organizers that Bragg recommends are spending their lives more fruitfully than those who just drive home and drown their troubles away, be it with alcohol, video games, Fudge Rounds, or name your drug of choice (sugar and movies for me). But the struggle for rights engaged in by the unions subjects itself to the same epithymetic program that allows addiction to grow unchecked. And corruption. Plenty of the comments under Bragg’s video on YouTube (curiously not seen if sorted by Top Comments) cite how corrupt and unhelpful unions have been in practice. That’s the meaning of one of Bragg’s lyrics that I know he doesn’t intend: “You’ll see where the problem really lies / when the union comes around.” That’s not at all to despair in the relative value of unions any more than in the relative value of businesses. Susceptible to corruption or not, unionizing suffices as some kind of labor movement sorely needed as a check on corporate greed... but as a religion, it’s rot. We need a reason to live, a reason to strive: a logos that can harness our ferocious passions — our aching desire to devour what attracts us and our manic compulsion to control what repels us — for good. America and all the West have the opposite of that.

IV. Anxiety and depression vs. prayer and fasting

The polarity of longing and lording is inevitable in this fallen world. But in the Godman Christ, who defeats the devil, sin, and death, it is overcome. He has defeated them, He will defeat them, and He defeats them even now. It is an eternal event to which we have been given access. In the philokalic tradition of His Body the Church, we find the richest knowledge of purification: how the passions work, how their destructive behavior is overcome, and how they are converted to the good in the love of God and neighbor.

I have in my mind a character I’ve conjured in my imagination, that of a brilliant young man gifted in physics. His ambitions are pointed high, and he seeks the master theory that can reconcile general relativity and quantum mechanics. He hears me describe the pattern between them, how it correlates to that of the passions, of dialectic, of commerce and politics, neurology, all of it. He agrees that our cosmic theories are shaped after the impassioned patterns of our souls, that the way we see things is determined by how we manage our appetitive and incensive powers. In order to see things in unity, then, he realizes he has to reshape the mind’s eye from the bottom up. He has to practice the virtues of dispassion and of love for God and neighbor. Until his eros for God and his agape for neighbor become fully active as a singularity, he will not have the eye with which to see things as they are. A theory of everything, after all, amounts to attaining the perspective of the uncreated Creator who can view everything that exists objectively and subjectively, to whom the distinction of outside and inside creation has been transcended. This young man, to meet his goal of reconciling the factions of modern physics, has to be deified in Christ.

But in pursuing the Gospel commandments he quickly figures out he cannot hold onto any scientific motivation. An erotic love for the cosmos instead of the One who created it, the manic drive to master the world through technology, the vanity of winning prizes and fame and having one’s name stuck to equations and stars and particles — the passions of epithymia, thymos, and logos are what drive modern science. But for its ultimate problems to be solved it has to let go of solving them entirely. Any moral slip-up by which this young man or anyone else willfully attempts to catch a glimpse of the master theory means automatically preventing oneself from seeing it. Either it will come of its own accord or not at all. It is an energy of God. And God’s not going to bestow it if one is still susceptible to pride and yet has a chance not to be. God loves us and wants us to have everything He does, but He won’t be responsible for our self-immolation. If He ever does offer someone the master theory, it would be because He knows that soul would try to refuse it out of superior love for Him, like Abraham sacrificing Isaac. Or, perhaps, in the end, He will give it to someone, the final prophet and king, unto that hero’s self-destruction, because his soul is impertinent, his vanity has subsumed him, his potential for repentance has been spent... and because God is gracious.

I assume the real life math of this sci-fi parable wouldn’t work out as I suspect; not since high school have I studied math or physics beyond the level of popular science. But there’s a lesson there that I think is solid, and it works analogously for politics. The source of the polarization at once tearing us apart and keeping us from escaping the agony is what religion calls sin. To relieve all the agony and the confusion, we have to reshape the soul’s activity from the bottom up. Only once the patterns of virtue are learned through praxis will the mind cut through our problems with wisdom and discernment: the almighty wisdom that comes from a source above the magnetic polarity of created things, and the loving discernment that knows how to direct the positive and negative charges according to their nature and in harmony with each other.

A father brings his demoniac son to Jesus to be healed (see Mark 9:14–29). This story about our spiritual condition has so much to say about our political condition; indeed the latter is effected by the former. This beleaguered father explains that the spirit ofttimes hath cast his son into fire and water, to destroy him. Fire and water are opposing elements symbolic of the opposing forces of the passions — in today’s parlance, anxiety and depression. Anxiety is like a burning fire, a thymic pestilence, this raging, frantic, uncontrollable lack of control; depression is like flooding water, an epithymetic sickness, this seductive appetite for a selfish pleasure acknowledged to be unattainable. Vectors pointing out, vectors pointing in. Anxiety is the abhorrent consciousness of our powerlessness to repel the pain that besets us; depression the embraced consciousness of being eternally removed from the pleasure we’ve resigned always to yearn for. Fire, and water.

An evil force is responsible for casting us into this polarized condition. Call it a demon, call it sin, call it the corruption of nature; all are in play. It both taketh us in (vectors in), and teareth us apart (vectors out), which is how the father describes the demon’s actions. The son as a result foameth, grindeth his teeth, and pineth away, illustrative of the tripartite passions. The overweening pride of our logos froths like bubbling liquid oozing from our heads and falling downward. Our thymic drive to exert power over that which is beyond our control is like teeth, grinding. The Greek word for ‘pines away’ contains a root meaning to dry up; it refers to the withering caused by unquenchable epithymetic thirst.

I’m able to write formulaically about these afflictions, because they are formulaic; they’re predictable and boring, vectors going out one end, the same vectors going in the other end — the eternal return of the same.

Again: Depression is an erotic appetite for pain in epithymetic acceptance of the combined reality of pleasure and pain, despairing of any existence free of evil. Intellectually intelligent people, at least those perceptive enough to mark the cohabitation of pleasure and pain within each other, are prone to this.

Anxiety is a spurned condition that will not go away, an awareness of hateful pain’s inescapable presence within sought-for pleasure, seemingly no matter what one does. Emotionally intelligent people, at least those sensitive enough to feel every aspect of the forces of the world and the self upon themselves, are prone to this.

The poles are contained within each other. Sometimes people are so emotionally intelligent, it comes around and effects an intellectual intelligence as well. Sometimes people are so intellectually intelligent, it comes around and effects an emotional intelligence as well. Sometimes depressed people feel anxious; sometimes anxious people feel depressed. In such cases the one is contained in the other. I think it’s hard to be both at the same time at full blast. Normally, either you’re rejecting the awareness of pain’s presence within pleasure, or you’re accepting its embrace. Bodies of water don’t often catch fire. It takes another ingredient — a spirit, an enchantment — for that to happen. (It’s not pleasant.)

The spirit afflicting the father’s son is called by Jesus deaf and dumb, for it passes those qualities onto the boy. When you’re deaf and dumb, the logoi of creation neither come into you nor go out of you. You’re divorced from God, from the Logos. Such ailments are humanly incurable; the disciples couldn’t heal him by themselves. Jesus, the transfigured Godman (this story meaningfully takes place directly after descending Mt. Tabor), both is the solution and tells us the solution: “This kind can come forth by nothing but by prayer and fasting.” No manner of humanist bargaining or rationalization can produce a different answer from this. The solution to our affliction is prayer and fasting.

Fasting here stands for thymic abstinence from our impassioned attachment to earthly things, indeed to all created things, not just food. Our attachment to heaven and earth through our thoughts and senses just means attachment to ourselves, soul and body. Prayer conversely is the attractive union of man to our uncreated Creator. The fire of anxiety and the water of depression are incurred by the attachment to worldly things, things that by nature are predicated on having been brought into being from non-being and thus have the polarity of opposites within them. Material wealth around the globe is on the rise and has been trending upward for a long while. Extreme poverty is diminishing, and its demise is within reach. We care most of all about material well-being, and so we’ve gotten good at advancing it. And as a result we’re experiencing apocalyptic levels of fear, anxiety, and depression. It turns out we really can’t live by bread alone. Our souls are starving to death. And no, Billy Bragg, unionizing is not going to fix this. We need fasting, not so as to starve our bodies to death the way we treat our souls now, but so as to allow both our souls and our bodies to live in unity according to a higher principle.

The Logos to whom we should be attaching ourselves in prayer, that higher principle, is not created out of non-being and so has no opposite, being immune to polarity. The prayerful appeal to such a power greater than ourselves (à la the twelve-step program) is absolutely necessary here. If we rely on anything created to save us, we will be cast right back down into the polarity of fire and water. So now I should describe more practically how we are rescued from depression and anxiety, and why it relies on a divine power greater than ourselves, to whom we should be praying. Though the remedies I’ll mention are in response to formulaic afflictions, it nonetheless will be harder to write about them formulaically because unlike the afflictions, the remedies do not trace the bounded pattern of the eternal return of the same; they represent paths to the eternal return of a boundless, absolute Other. Whereas anxiety and depression are entirely ours, the paths away from them do not belong to us and can’t be defined as if they do. Experiences can be described, though, and that’s what I’ll attempt.

If you’re prey to depression, you’re probably already attracted to beauty, but it’s the worldly, corrupt beauty that has death inside it. And so you’re a solipsistic brat who’s full of negativity and a drag to be around — in the eyes of those polarized against depression. The prescribed activity for you is selfless works of charity. You may be convinced you’re worthless, capable of nothing good that isn’t mixed with evil. But if you try committing altruistic acts assisting those in need, something as simple as volunteering at a soup kitchen or a nursing home on a regular basis, you’ll be drawn gently into the admission that good can be accomplished even through a brat such as yourself, that self-sacrificial love is possible, that there exists a beauty that is pure good and not evil, and that it is greater than any beauty you have ever known. For this to work, the altruism you are imitating, even if imperfectly, must itself be real. It must be coming, ultimately — imagistically — from that greater power, the Creator who has no opposite, the Life that knows no death.

Conversely, if you are prey to anxiety, you probably already have an innate repulsion to what’s wrong (in yourself and in the world), but your conviction is worldly and corrupt and leads inexorably to death all the same. And so you’re a needy headcase who’s full of negativity and a bear to be around — in the eyes of those polarized against anxiety. The prescribed activity for you is participating in enchantment by beauty. You may have conceded control of your soul to your manic thoughts and may be despairing of doing otherwise as long as you’re alive. But in the presence of enchanted beauty, in either nature or art or friendship — by, say, learning how to hunt honorably, in accordance with nature, or participating in a traditional art form requiring discipline, like folk dance or icon painting — the attention of your anarchic thoughts can be commanded by divine patterns in creation, such that you’ll be drawn gently into the admission that experiencing peace in this world is possible, that there exists an order that is pure good and not evil, and that it is greater and more merciful than any justice you have ever known. What’s more, the thoughts you despair of ever being anything but an affliction can be made right and useful to yourself and others. For this to work, the beauty you’re enchanting yourself with, even if imperfectly, must be coming, ultimately — imagistically — from that power greater than ourselves, the Peace that, by way of the Cross, overwhelms all agony, the Beauty that has the goodness of real altruism inside it.

If it’s the worldly, corrupt beauty that depressed people feed themselves on, however, inescapable death will again make its presence known, and the fires of anxiety will be relit. Or you’ll suspect this bad result from the beginning, the fires will never go out, and you’ll reject the counsel, skipping over any respite. The polar opposite trap exists for depressed people seeking a mode of charity based on the manic political ideology of the anxious. Such ideology has death inside it, manifest in the use of force necessary for its application. Tyranny results, and that feeds back into the cycles of depression. But those who are more perceptive will see the tyranny from a distance and never emerge from the waters, rejecting any acts of charity and resolving not to be of any good to anyone, least of all to themselves.

Prayer — both communal prayer according to the liturgical cycles of the Church and private prayer in one’s closet with the door closed — has to be the ultimate destination of our enchantment and of our charity. Prayer to that Power greater than ourselves, not subject to the polarity of being and non-being (to say nothing of the polarity of pleasure-seeking and pain-avoiding from which we must fast), is absolutely necessary to rescue us from the deaf and dumb spirit that taketh us in and teareth us apart. The fires of anxiety and waters of depression are not overcome any other way. Humanism is not enough.

But just as our pathologies are not simple — because the abusive, co‑dependent relationships of our souls and bodies are not simple — in neither case of fire or water is this a simple fix. Those prone to depression applying themselves to charitable living may find themselves facing the unfamiliar challenges of anxiety. Those prone to anxiety searching for peace in enchanted beauty may fall into unfamiliar modes of depression. Our Maker intends us to rise above each pole so as to be a free master of the entire axis, according to His likeness. The road to perfection is long, but it’s lined with enchantment and charity the entire way; in truth, it’s the only road worth traveling in this life. Plus, it’s addictive in the most liberating way imaginable. True freedom is freedom from corruption, freedom from the spirit that taketh us in and teareth us apart. Freedom to become the Body of Christ, to become heir of God by adoption, to become God by grace.

I hope the applicability of this discussion to political affairs is not lost on any readers. It should be obvious — even before I go on some long spiel about Plato’s Republic — that “government of the people, by the people, for the people” (as Lincoln phrased it in the Gettysburg Address) is going to depend entirely on the mental health of said people. Mental health is what we materialists call it anyway. In truth it is spiritual health, though assuredly afflictions like anxiety and depression can burn themselves in our flesh and be passed from generation to generation. The anxiety or depression that any one person suffers is about more than just that one person; causes are spread throughout society as well. Hence the remedies I describe are psychologically based but not without bodily participation, and communal acts of charity and traditional modes of enchantment are to be preferred over any independent, novel behavior. Divine love too can burn itself in the flesh and be passed through the generations, in ways that counter the damage of the passions. Moreover, since our political polarization of left and right is patterned after the polarity of desire and anger, it follows that the path to spiritual health should provide the pattern of political solutions. This can’t be a mere intellectual game, though. For the patterns of health to emerge into the political sphere, they have to be actualized along actual paths of spiritual health, attained through purification with bodily participation and a social dimension.

A temptation exists, because the psychological polarity I’m describing accords with the patterns of dialectical reasoning, to take the knowledge of the passions and try to manage them intellectually, to work it all out in one’s head — to replace actual purification with scholastic rumination. Pondering things according to logos (in, for example, an overlong Substack essay) is of course a good thing (please like and share!). But it can become a bad thing if it doesn’t lead one to engaging in psychological purification by means of prayer and fasting, or put more simply, to repentance. When a depressed person seeks allopathic treatment by means of thymic acts of charity, this is not dialectical synthesis. Likewise with the anxious person seeking allopathic treatment by participation in enchanted beauty — this is not dialectical synthesis, but a journey towards the prayer and fasting that successfully detach one from modes of dialectical synthesis, from the polarization of the passions.

As with passions, so with political forces. There’s a temptation to try to work out political problems all in one’s head. Knowledge is power. So, the unpurified mind thinks, let’s exert that power; maybe then we’ll get what we want. Reason is thus put in service of the passions instead of the other way around — a quite unreasonable arrangement. Or worse, it could be put into service of no higher power other than itself. Instead of serving the Logos, we could try to be the logos. Politically, we could think, well, if the Democrats are epithymia and the Republicans are thymos, we need a third party to represent logos. But the impertinence of rationality is a more horrible force than any epithymetic decadence or thymic tyranny. The pride of humanistic rationalism is in fact what unleashes those lower forces of destruction, like weeping and gnashing of teeth.

V. The end of democracy, and quixotic voting

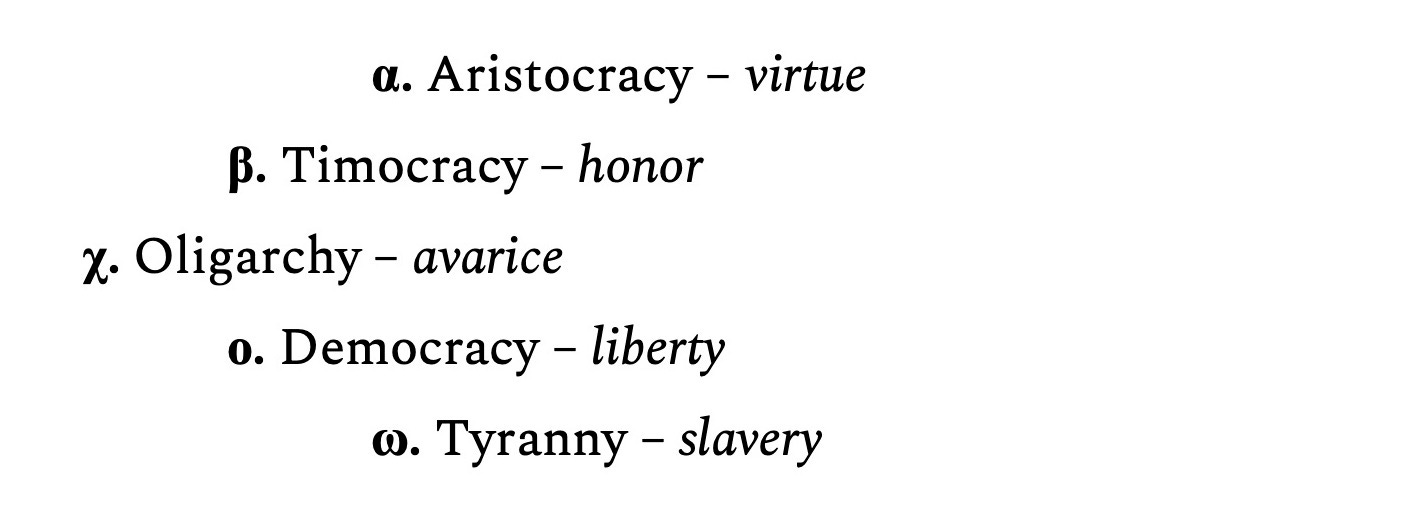

Plato in Books VIII and IX of the Republic traces out his theoretical genealogy of governments based on his understanding of tripartite psychology. The stages are fivefold and are both linear and chiastic. First (α.) everything is in order psychologically and politically. A completely just man, with his incensive and appetitive faculties subjected to his rational faculty, serves as the philosopher-king of a monarchical aristocracy based on the rule of virtue. (Aristos means noble and best and is related to arete, which word, translatable as virtue but encompassing all value, was central to ancient Greek culture.) Then, however (β.), corruption creeps in, and the incensive drive for honor among men begins to be what motivates politics instead of love of virtue. This is called timocracy. It entails property ownership and the private gathering of wealth, both so as to impress others socially and to satisfy the appetites of women. Honor is corrupted by such wealth in the next stage (χ.), oligarchy, when epithymetic appetites for wealth take over the public sphere and harden into a class structure where a few rich rule over an impoverished many, and beggars and thieves run rampant in the streets. This genealogy may be linear, but Plato upholds a strict hierarchy between the incensive and appetitive faculties, very much denigrating desire relative to anger (in Christian sources the relationship is much more dynamic). Hence the middle stage of oligarchy, by prioritizing desire, represents a chiastic bottoming out in the fivefold process.

Yet the linear degradation of corruption continues. Next (ο.), the injustice of the oligarchic class system inspires a democratic revolt. Whereas timocracy in the second step represents the fall from the rational faculty to the incensive faculty, democracy in the fourth step represents the joining of the incensive faculty to the cause of the appetitive faculty. In order to satisfy appetites, the demos strives thymically for liberty and equality. This psychological combination yields a wide variety of outcomes: individuals so governed could even stumble into virtue, but not in any way that would influence the direction of government. Socially this is an anarchic state wherein anything is possible on the individual level, but from which the next stage (ω.), tyranny, is inevitable. Once the passions are politically liberated, a tyrant naturally arises that manipulates them in others to serve his own liberated egoism. Loyalty is won through the liberal satisfaction of appetitive addictions; obedience is achieved through stoking anger against foreign nations in constant wars. The ideal philosopher-king marshals the powers of the passions for virtue; the tyrant does the same for vice. His power consolidated, he yanks the chains of slavery slipped unawares on all his people, but he himself is most miserable of all, enslaved to the fear of losing his dominion.

This speculative theory of Plato’s does not match the complexity of history in any detailed fashion, yet the patterns he traces all feel familiar. Aristocracy as he describes it couldn’t have existed since Eden. Timocracy in our day and age is a distant memory. What we have now seems to be an ice cream swirl of oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny, as Plato describes them. In the 20th century, fascism and communism gave us rushed foretastes of full-blown tyranny, but the democratic, American-led West has carved a different path, one slower and more deliberate. The way Plato prophetically describes the emergence of tyranny from democracy on account of the liberated passions is way, way too relatable.

Let’s compare notes, then, with a more local prophet who told us what he thought would happen if factional parties were allowed to rule American politics. I referred to it earlier, but this now is what George Washington said in his farewell address at the end of his presidency in 1796, seemingly under some Platonic influence:

Let me now take a more comprehensive view and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party, generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but in those of the popular form it is seen in its greatest rankness and is truly their worst enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight) the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and the duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of the government and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true — and in governments of a monarchical cast patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency, it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose. And there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest instead of warming it should consume.

In retrospect it would appear the father of my country had not a little wisdom about its vulnerability to disintegration. The admission, moreover, that a monarchical government has the capacity to tolerate the passions of party whereas an elective government does not is downright remarkable coming from a revolutionary who threw off the crown and refused one for himself. He said also earlier in the address:

All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations under whatever plausible character with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction; to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common councils and modified by mutual interests. However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

A native-grown tyranny fueled by the polarization of the passions was very much on Washington’s mind. Indeed he saw it coming and could do nothing to stop it. Earlier in his adulthood he had been a tobacco farmer. This drug crop ran the Virginian economy; it was very lucrative at the market, but it stripped the soil of its nutrients and was not sustainable. Tenacious tobacco farming, with no regard for soil health, made colonial expansion westward, and all the violence that entailed, an economic necessity. Antichristian passions of desire and anger were thus unleashed on the continent. Washington played his role in that, but already in his thirties repented and converted to sustainable wheat farming. I imagine that it’s this wiser version of our national patriarch that’s able to warn his heirs against party factionalism.

Few were privileged to be as wise as he, however, and even those that were so privileged failed to be so wise. For the founding fathers to free their slaves according to their principles, for example, they had to live in a certain way to pull it off economically once they were gone. Washington at Mt. Vernon lived in just such a temperate way so as to free his slaves upon the deaths of him and his wife. Jefferson at Monticello, on the other hand — he who penned the line “all men are created equal” — lived a life of intellectual indulgence such that, on account of debts, he could not free his slaves upon his death, excepting only two he likely fathered, along with three of their relatives. A hundred and thirty were sold at auction. The generation of leaders that Washington admonished to hold themselves above corruption failed to heed his warning, and polarized passions erupted in the form of parties.

Here then is your semi-regular reminder that by serendipity Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson — the rival candidates who, like descending testicles, initiated the two-party system as soon as Washington said farewell — died the same day, Adams in Massachusetts and Jefferson in Virginia, on the Fourth of July, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

I have learned this fact a few times in my life, each time forgetting it only to relearn it with wonder. It is no meaningless happenstance. It is not just a neat historical button to place at the end of a PBS documentary. Profound mythological meaning about the United States, and about American democracy, is accessible within it. For one thing, the two parties, representing the poles of the lower passions, are coterminous. Elimination of one and not the other is not an objective possibility. Even when the War of 1812 discredited the waning Federalist Party and the fifth president James Monroe held polarization within his administration like a second Washington, the testicles descended again directly after him (in 1824), the dialectic reappearing along elitist and populist lines (conservative Whigs and Jacksonian Democrats). The negative partisanship dominating our era whereby each party behaves as if it wishes the other’s existence would end is wholly self-defeating. Like a magnetic field, you can’t eliminate one pole without eliminating both. Nor can one pole evade the vexation of polarity by detaching from the other. The same pattern of polarization between left and right is plainly visible within each side. True, according to string theory (a largely discredited attempt to reconcile modern physics), magnetic monopoles must exist — the stuff eliminationist political fantasies are made of — but they’ve never been found. Adams and Jefferson exist together or not at all. Perishing, they do so together.

And they do it on the Jubilee of the nation’s self-proclaimed existence. The symbolism of this timing is too rich. Fifty being the end of a cycle of seven sabbaths of years (7 × 7 = 49, plus one, the eighth day circumscribing all time) suggests that when the parties die, the nation comes to its end, symbolically speaking. To cease desiring or being indignant is for my nation to reach the end of its cycle — to lose its identity and expire. There’s a lot of truth in that. Or, since the Jubilee in Mosaic Law marks the liberation of slaves, the forgiveness of debts, and the restitution of all God-ordained ownership, the deaths of Adams and Jefferson on the Jubilee of Independence suggests that a dispassionate state free of polarized passions must be achieved for true liberty and justice to exist.

All of which sounds great, right, but what do we do till then? Well, the Jubilee system, were it ever followed, would not have spelled the end of trade; it would have just meant that you couldn’t trade land or slaves so much as loan them out against the Jubilee. American politics can’t and shouldn’t stop just because they’re corrupt. We should not be so eager to expire. What they should be doing is proceeding incrementally away from corruption and towards virtue in any way possible. Until politics are free of corruption, that means making corrupt choices. It’s an affront to our pride, but we’re not going to be able to choose absolute Good. That won’t be on the ballot. The only goods we’ll find are relative goods mixed with relative evils — which is not a call to despair. Despair, recall, is a prime ingredient of both anxiety and depression, the axis of weeping and gnashing of teeth that we’re trying to move away from. Rather, we humbly trade with what we have in order to increase our relative goods and decrease our relative evils. This pattern too we learn from our fight to attain virtue and to shed vice.

So that’s right: all this talk about polarization, and corruption, and tyranny, was all just a lead-up to my quixotic recommendation that citizens of democracies vote anyway. The world may be trying its damnedest to enact both poles of Nineteen Eighty-Four and A Brave New World at the same time; the whore of Babylon may be ready to mount the beast of ten horns (cf. Rev. 17), one foot in the stirrup; I still say vote anyway. Make it a write-in candidate if you have to. I can’t tell people who to vote for, or argue that it’s even important who they vote for. Due to competing moral systems (Trader and Guardian), both of which are necessary, different people will prioritize different issues. It’s no matter. I see no reason why anyone of one value system, either thymic or epithymetic, would need to convert to the other. They merely need to be virtuous within the moral system in which they find themselves and cooperate with those who do the same across the aisle. Lancelot is a knight, and Guinevere is a queen. The queen doesn’t need to become a knight, and the knight doesn’t need to become a queen. What we need is for them to be virtuous versions of themselves — and for King Arthur (the logos presiding over thymos and epithymia) to keep his house in order. As long as my fellow citizens strive for virtue, not only following their consciences but actively seeking to educate their consciences, and vote somehow for someone so as not to despair in our potential for redemption, the American Camelot has a chance to transcend its limitations.

Submitting oneself to voting, I think, is a meaningful part of that, but it’s not the voting that’s the agent of salvation; it’s the divine virtue of caring for our neighbors and not yielding to anarchy in despair. A democracy in which people don’t vote is a literal anarchy. Like faith without works, a democracy without votes is dead. You’re not going to be able to save your country with your vote, any more than you can be saved by your works, it is true. Behaving as if you have the power to save your country, or that politicians have the power to save the country, or even that we all collectively have the power to save the country, is atheistic hubris. The plague of sin and death spawning all political corruption is greater and more powerful than all that. The power that we do have, which we can activate in how we approach voting, the same way as we approach living, is not to save our country, but to make our country worth saving. By living virtuous lives we make our country worth saving. We make our nation a hospitable place to the One who has the power to save, calling down His favor so as to secure our democracy for good.

The idea that our democracy, already enslaved by technocratic means, could possibly wrestle free from the inevitability of tyranny, from the poles of Huxley and Orwell, is quixotic idealism, I admit. Our current party system resembles the Roman province of Judea, with our electoral choices confined to Pilate and Herod, those entrenched foes who found common ground only in the crucifixion of the Messiah (cf. Luke 23:12). Oh, and for a third-party candidate, we’re welcome to support an ineffectual Barabbas if we’d like. No, if the Christians who see things this way don’t vote, I can’t much blame them (so long as they pursue virtue without despair). But if their argument depicts voting as the ritual of a secular religion that rejects the sovereignty of God, and therefore as something that shouldn’t be participated in by Christians, I would counter that, well, it is part of a state liturgy, no doubt. But having a state liturgy is not dialectically opposed to having a sacred liturgy; like soul and body, it is indeed natural to hold both in their proper hierarchical order. Expecting your state liturgy, meanwhile, to be as pure as your sacred liturgy, without any ailments, is not realistic. In humility you should do what you can within your given situation to make your nation’s government better, healthier — that is, worthier of salvation.